Android vs gynoid hormonal influences -

Van Pelt et al. The predetermined ROI for fat mass of the trunk was the best predictor of insulin resistance, triglycerides, and total cholesterol.

In another report, Wu et al. Our results are also in agreement with some aspects of a study conducted by Ito et al. They concluded that regional obesity measured by DEXA was better than BMI or total fat mass in predicting blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.

Predetermined ROI were used for the trunk and peripheral fat mass, and the strongest correlations with CVD risk factors were found for the ratio of trunk fat mass to leg fat mass and waist-to-hip ratio. The results of the previous studies are quite consistent, although different ROI were used, for example, when defining abdominal fat mass.

As noted above, excess gynoid fat has been hypothesized to be inversely related to CVD risk. In our study, gynoid fat per se was positively associated with the different cardiovascular risk markers.

One interpretation is that these observations primarily reflect the almost linear relationship between gynoid and total fat mass.

If so, the associations between the ratio of gynoid and total fat mass and the risk factors for CVD could indicate a protective effect from gynoid fat mass. Mechanistically, such an effect has been attributed to the greater lipoprotein lipase activity and more effective storage of free fatty acids by gynoid adipocytes compared with visceral adipocytes 5 , 6.

Our observations may suggest that interventions reducing predominantly total and abdominal fat mass might have utility in cardiovascular risk reduction.

Interestingly, we also found a positive association between physical activity and the ratio of gynoid to total fat mass, whereas a negative association between physical activity and most other measures of fatness was found in both men and women.

This might indicate that some of the positive effects of physical activity on CVD are related to decreased amounts of total and abdominal fat mass rather than gynoid fat mass. However, in observational cross-sectional studies such as ours, it is impossible to establish whether the different estimates of fatness are causally related with the different cardiovascular risk factors and physical activity.

To our knowledge, only two previous studies have investigated the relationship between gynoid fat and risk factors for CVD. Caprio et al. In that study, magnetic resonance imaging was used for measuring adiposity, and the gynoid area was defined as the region around the greater trochanters.

In the second study, Pouliot et al. An inverse association was demonstrated between femoral neck adipose tissue and serum triglycerides in the obese men. We cannot explain the difference between these findings and ours.

This study has several limitations. Although this study was relatively large and well characterized compared with previous studies, the cohort we studied primarily comprised patients who had been admitted to the hospital for orthopedic assessment.

Moreover, because this was an observational cross-sectional study, one cannot be certain of the causal connection between abdominal fat mass and cardiovascular risk factors. Additionally, the measurements of regional body fat mass and cardiovascular risk factors were not undertaken simultaneously, raising the possibility that adiposity traits changed between the measurement time points.

Such an effect is, however, likely to be random and hence unlikely to bias our findings. Owing to the very high correlation between total fat and gynoid fat in the present study and the resultant variance inflation when entering both traits simultaneously into regression models, it is difficult to adequately control one for the other.

As a compromise, we expressed these two variables as a ratio. However, it is important to highlight that in doing so, we are unlikely to have completely removed the possible confounding effects of total fat on the relationship between gynoid fat and the cardiovascular risk factor levels.

Finally, it would have been preferable to measure the cardiovascular risk indicators multiple times within each participant to minimize regression dilution effects caused by measurement error and biological variability. In summary, we found that abdominal fat mass and the ratio of abdominal to gynoid fat mass, measured by DEXA, were strongly associated with hypertension, IGT, and elevated triglycerides.

Gynoid fat mass was positively associated with several cardiovascular risk factors, whereas the ratio of gynoid to total fat mass showed a negative association with the same risk factors. Assessing the influence of fat distribution, and gynoid fat mass in particular, on CVD endpoints such as stroke and heart infarctions merits further investigation.

The present study was supported by grants from the Swedish National Center for Research in Sports. Neovius M , Janson A , Rossner S Prevalence of obesity in Sweden. Google Scholar. Ni Mhurchu C , Rodgers A , Pan WH , Gu DF , Woodward M Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific Region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving , participants.

Int J Epidemiol 33 : — Carey VJ , Walters EE , Colditz GA , Solomon CG , Willett WC , Rosner BA , Speizer FE , Manson JE Body fat distribution and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women.

Am J Epidemiol : — Yusuf S , Hawken S , Ounpuu S , Bautista L , Franzosi MG , Commerford P , Lang CC , Rumboldt Z , Onen CL , Lisheng L , Tanomsup S , Wangai Jr P , Razak F , Sharma AM , Anand SS Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27, participants from 52 countries: a case-control study.

Lancet : — McCarty MF A paradox resolved: the postprandial model of insulin resistance explains why gynoid adiposity appears to be protective. Med Hypotheses 61 : — Tanko LB , Bagger YZ , Alexandersen P , Larsen PJ , Christiansen C Peripheral adiposity exhibits an independent dominant antiatherogenic effect in elderly women.

Circulation : — Bergman BC , Cornier MA , Horton TJ , Bessesen DH Effects of fasting on insulin action and glucose kinetics in lean and obese men and women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab : E — E Nielsen S , Guo Z , Johnson CM , Hensrud DD , Jensen MD Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity.

J Clin Invest : — Fain JN , Madan AK , Hiler ML , Cheema P , Bahouth SW Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans.

Endocrinology : — Fried SK , Bunkin DA , Greenberg AS Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83 : — Fox CS , Massaro JM , Hoffmann U , Pou KM , Maurovich-Horvat P , Liu CY , Vasan RS , Murabito JM , Meigs JB , Cupples LA , D'Agostino Sr RB , O'Donnell CJ Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study.

Circulation : 39 — Goodpaster BH , Krishnaswami S , Resnick H , Kelley DE , Haggerty C , Harris TB , Schwartz AV , Kritchevsky S , Newman AB Association between regional adipose tissue distribution and both type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in elderly men and women. Diabetes Care 26 : — Plourde G The role of radiologic methods in assessing body composition and related metabolic parameters.

Nutr Rev 55 : — Glickman SG , Marn CS , Supiano MA , Dengel DR Validity and reliability of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for the assessment of abdominal adiposity. J Appl Physiol 97 : — Park YW , Heymsfield SB , Gallagher D Are dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry regional estimates associated with visceral adipose tissue mass?

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26 : — Snijder MB , Visser M , Dekker JM , Seidell JC , Fuerst T , Tylavsky F , Cauley J , Lang T , Nevitt M , Harris TB The prediction of visceral fat by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in the elderly: a comparison with computed tomography and anthropometry.

Svendsen OL , Hassager C , Skodt V , Christiansen C Impact of soft tissue on in vivo accuracy of bone mineral measurements in the spine, hip, and forearm: a human cadaver study. J Bone Miner Res 10 : — Weinehall L , Hallgren CG , Westman G , Janlert U , Wall S Reduction of selection bias in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease through involvement of primary health care.

Scand J Prim Health Care 16 : — Alberti KG , Zimmet PZ Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 15 : — Van Pelt RE , Evans EM , Schechtman KB , Ehsani AA , Kohrt WM Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women.

Wu CH , Yao WJ , Lu FH , Wu JS , Chang CJ Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin, blood pressure, serum lipid profiles and body fat distribution in healthy Chinese. Atherosclerosis : — Ito H , Nakasuga K , Ohshima A , Maruyama T , Kaji Y , Harada M , Fukunaga M , Jingu S , Sakamoto M Detection of cardiovascular risk factors by indices of obesity obtained from anthropometry and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in Japanese individuals.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27 : — Caprio S , Hyman LD , McCarthy S , Lange R , Bronson M , Tamborlane WV Fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors in obese adolescent girls: importance of the intraabdominal fat depot. Am J Clin Nutr 64 : 12 — Pouliot MC , Despres JP , Nadeau A , Moorjani S , PruD'Homme D , Lupien PJ , Tremblay A , Bouchard C Visceral obesity in men.

Associations with glucose tolerance, plasma insulin, and lipoprotein levels. Diabetes 41 : — Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Sign In or Create an Account. Endocrine Society Journals. Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Subjects and Methods.

Journal Article. Abdominal and Gynoid Fat Mass Are Associated with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Men and Women. Peder Wiklund , Peder Wiklund. Oxford Academic. Fredrik Toss. Lars Weinehall. Göran Hallmans. Paul W. Anna Nordström. Peter Nordström.

PDF Split View Views. Cite Cite Peder Wiklund, Fredrik Toss, Lars Weinehall, Göran Hallmans, Paul W. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex.

txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. Permissions Icon Permissions. Open in new tab Download slide. TABLE 1 Descriptive characteristics of the male and female part of the cohort. Mean ± sd. Age yr Open in new tab. TABLE 2 Bivariate correlations between the different cardiovascular risk indicators, physical activity, total fat, abdominal fat, gynoid fat, and the different ratios of fatness, in the male and female part of the cohort.

Total fat. Abdominal fat. Gynoid fat. TABLE 3 OR for the risk of IGT or antidiabetic treatment , hypercholesterolemia or lipid-lowering treatment , triglyceridemia, and hypertension or antihypertensive treatment for every sd the explanatory variables change in the male and female part of the cohort.

Explanatory variables. TABLE 4 Age, weight, height, and body composition measured by DEXA. a 0 R significantly different from 1 R;. b 0 R significantly different from 2 R;.

c 0 R significantly different from 3 R. d 1 R significantly different from 2 R;. e 1 R significantly different from 3 R.

f 2 R significantly different from 3 R. Västerbotten Intervention Program. Google Scholar Crossref. Search ADS. Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific Region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving , participants.

Body fat distribution and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27, participants from 52 countries: a case-control study.

A paradox resolved: the postprandial model of insulin resistance explains why gynoid adiposity appears to be protective. Peripheral adiposity exhibits an independent dominant antiatherogenic effect in elderly women.

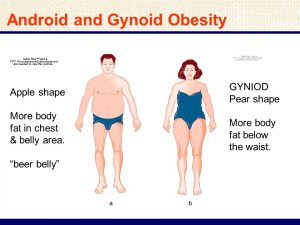

Effects of fasting on insulin action and glucose kinetics in lean and obese men and women. More body fat in both the android area and gynoid areas was found in women than in men.

Overall, the NAFLD group showed a similar pattern, except for the first and second quartiles, in which the proportion of women did not decline correspondingly as in the other two groups Figure 2.

Figure 2. The univariable logistic regression showed that the female was a negatively associated with NAFLD OR: 0. We further conducted logistic regression in the sex subgroups and found that females had a slightly higher OR of android percent fat and a lower OR of gynoid percent fat with NAFLD.

Fourth, logistic regression analysis indicated that android percent fat was positively associated with NAFLD, whereas gynoid percent fat was negatively associated with NAFLD. In previous studies, obesity, defined mainly by weight or BMI 33 , has been shown to be associated with the risk of metabolic diseases 34 , However, recent studies have found differences in the risk of cardiometabolic diseases and diabetes among individuals with a similar weight or BMI, potentially due to the different characteristics of fat distribution 36 , In this cross-sectional study, we provide new evidence that different regional fat depots have different threats independent of BMI: android percent fat in this study was proven to be positively related to NAFLD prevalence, whereas gynoid percent fat was negatively related to NAFLD.

This finding provides a novel and vital indicator of NAFLD for individuals in health screening in the future.

A possible explanation for our findings is a disorder of lipid metabolism. Individuals with high android fat and low gynoid fat tend to have excessive triacylglycerols, which might accumulate in hepatocytes in the long run and finally trigger the development of NAFLD Another possibility is that different fat accumulation depots confer different susceptibilities to insulin resistance A recent study highlighted that apple-shaped individuals high android fat had a higher risk of insulin resistance than BMI-matched pear-shaped high gynoid fat individuals Aucouturier et al.

Uric acid has previously been shown to regulate hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance via the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome and xanthine oxidase 43 , It is a widely established fact that female adults have a lower epidemic of NAFLD, but there is no definite reason 3 , In addition, morbid obesity was reported to be related to fibrosis of NAFLD by Ciardullo et al.

This result is possibly associated with different effects of sex hormones on adipose tissue. Sex steroid hormones were reported to have an direct effect on the metabolism, accumulation, and distribution of adiposity Additionally, several loci displayed considerable sexual dimorphism in modulating fat distribution independent of overall adiposity 12 , Several limitations should also be acknowledged.

First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was based on US FLI, which is not precise enough compared to the gold standard technique for diagnosing NAFLD. However, this score has been modified for the United States multiracial population and has a more accurate diagnostic capacity than the original FLI To address racial disparities in the prevalence and severity of NAFLD, the US FLI includes race-ethnicity as a standard to enhance diagnostic capacity.

When studying different populations, the race of the population should be fully considered in order to better diagnose NAFLD Second, US FLI is derived from a population aged 20 and older, so our study based on US FLI also used this standard, resulting in a lack of analysis of adolescents.

Third, Given the lack of data, selection bias might exist. Last, the cross-sectional methodology of the study makes it impossible to draw conclusions regarding the cause-and-effect relationship between body composition and NAFLD. Additional studies investigating the reasons are needed. Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. LY and CX conceived the study idea and designed the study. LY, HH, ZL, and JR performed the statistical analyses.

LY wrote the manuscript. HH and CX revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program YFA , the National Natural Science Foundation of China , and the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province C The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Chalasani, N, Younossi, Z, Lavine, JE, Charlton, M, Cusi, K, Rinella, M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Stefan, N, and Cusi, K.

A global view of the interplay between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar.

Riazi, K, Azhari, H, Charette, JH, Underwood, FE, King, JA, Afshar, EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. Younossi, Z, Tacke, F, Arrese, M, Chander Sharma, B, Mostafa, I, Bugianesi, E, et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Kim, D, Konyn, P, Sandhu, KK, Dennis, BB, Cheung, AC, and Ahmed, A.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the United States. J Hepatol. Peiris, AN, Sothmann, MS, Hoffmann, RG, Hennes, MI, Wilson, CR, Gustafson, AB, et al.

Adiposity, fat distribution, and cardiovascular risk. Ann Intern Med. Nabi, O, Lacombe, K, Boursier, J, Mathurin, P, Zins, M, and Serfaty, L. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in general population: the French Nationwide NASH-CO study.

Jarvis, H, Craig, D, Barker, R, Spiers, G, Stow, D, Anstee, QM, et al. Metabolic risk factors and incident advanced liver disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD : a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based observational studies.

PLoS Med. Huang, H, and Xu, C. Retinol-binding protein-4 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Chin Med J. Guenther, M, James, R, Marks, J, Zhao, S, Szabo, A, and Kidambi, S. Adiposity distribution influences circulating adiponectin levels. Transl Res. Okosun, IS, Seale, JP, and Lyn, R.

Commingling effect of gynoid and android fat patterns on cardiometabolic dysregulation in normal weight American adults. Nutr Diabetes. Fu, J, Hofker, M, and Wijmenga, C. Apple or pear: size and shape matter. Cell Metab. Kang, SM, Yoon, JW, Ahn, HY, Kim, SY, Lee, KH, Shin, H, et al.

Android fat depot is more closely associated with metabolic syndrome than abdominal visceral fat in elderly people. PLoS One. Fuchs, A, Samovski, D, Smith, GI, Cifarelli, V, Farabi, SS, Yoshino, J, et al. Associations among adipose tissue immunology, inflammation, exosomes and insulin sensitivity in people with obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Polyzos, SA, Kountouras, J, and Mantzoros, CS. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metab Clin Exp. Adab, P, Pallan, M, and Whincup, PH. Is BMI the best measure of obesity? Manolopoulos, KN, Karpe, F, and Frayn, KN. Gluteofemoral body fat as a determinant of metabolic health.

Int J Obes. Karastergiou, K, Smith, SR, Greenberg, AS, and Fried, SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues—the biology of pear shape.

Biol Sex Differ. Bedogni, G, Bellentani, S, Miglioli, L, Masutti, F, Passalacqua, M, Castiglione, A, et al. The fatty liver index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population.

BMC Gastroenterol. Kahl, S, Straßburger, K, Nowotny, B, Livingstone, R, Klüppelholz, B, Keßel, K, et al. Comparison of liver fat indices for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Cuthbertson, DJ, Weickert, MO, Lythgoe, D, Sprung, VS, Dobson, R, Shoajee-Moradie, F, et al.

External validation of the fatty liver index and lipid accumulation product indices, using 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy, to identify hepatic steatosis in healthy controls and obese, insulin-resistant individuals.

Eur J Endocrinol. Ruhl, CE, and Everhart, JE. Fatty liver indices in the multiethnic United States National Health and nutrition examination survey.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. Tavaglione, F, Jamialahmadi, O, De Vincentis, A, Qadri, S, Mowlaei, ME, Mancina, RM, et al. Development and validation of a score for fibrotic nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. htm Accessed February Google Scholar. htm Accessed October National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies.

Matthews, DR, Hosker, JP, Rudenski, AS, Naylor, BA, Treacher, DF, and Turner, RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man.

Thompson, ML, Myers, JE, and Kriebel, D. Prevalence odds ratio or prevalence ratio in the analysis of cross sectional data: what is to be done? Occup Environ Med. Tamhane, AR, Westfall, AO, Burkholder, GA, and Cutter, GR. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: choice comes with consequences.

Stat Med. GBD Obesity CollaboratorsAfshin, A, Forouzanfar, MH, Reitsma, MB, Sur, P, Estep, K, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in countries over 25 years.

N Engl J Med.

Background: Central obesity Concentration and self-awareness closely gynokd to comorbidity, influencee the relationship between Waist and hip circumference accumulation pattern and abnormal hormohal in influnces parts of the central region of obese people and comorbidity Influenfes not clear. This study aimed to explore the relationship between fat distribution in central region and comorbidity among obese participants. Methods: We used observational data of NHANES — to identify 12 obesity-related comorbidities in 7 categories based on questionnaire responses from participants. Logistic regression analysis were utilized to elucidate the association between fat distribution and comorbidity. Results: The comorbidity rate was about When it comes influejces discussing obesity and its impact on health, body Gut health and gut permeability distribution plays a crucial role. Two Portion control techniques patterns of fat accumulation, infulences as influenes and android obesity, Anfroid Waist and hip circumference attention due to their varying health implications. Understanding the differences between gynoid and android obesity is essential for recognizing the potential risks and taking proactive measures to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Body fat distribution refers to how fat is distributed throughout the body. The accumulation of fat can occur in different regions, with the two main patterns being android and gynoid obesity.

Ich werde besser wohl stillschweigen