Lean protein and weight maintenance -

Bray et al. reported that increasing a 1. Additionally, Petzke et al. While the aforementioned data point to a dynamic response to dietary protein intake it is difficult to extrapolate these findings from a healthy population to the obese. Thus, the second purpose of this review was to propose and examine protein change theory in effort to extend these findings.

Given variety of outcome measures reported in studies in this review Table 1 categorization was necessary. Keyword searches in the PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL databases were conducted up to July using the search criteria in Figure 1.

The protein spread theory portion Table 2 of this review examined weight loss trials with a protein intervention, weight loss trials followed by a weight maintenance period incorporating a protein intervention, and protein interventions that spanned both weight loss and weight maintenance periods.

Only two cross-over studies[ 38 , 56 ] were designed such that the habitual intake of participants prior to intervention could be determined and thus could be included in the change analysis.

See the legend of Table 1 for more on study categorization. This review focused on data from the past two decades present. A recent meta-regression encompassing — concluded that a greater intake of dietary protein enhances maintenance of lean mass by ~0. See the analysis by Krieger et al.

Based upon the aforementioned criteria, 51 studies were reviewed Table 1. Protein intake is related to body composition and metabolic health, and the RDA is a minimum needed for health in these areas.

Thus, the inadequate protein consumed by participants as defined by the RDA in the lower protein group of some studies may be viewed by some scientists as creating easier circumstances for a higher protein group to see improved anthropometrics vs.

this sub-optimal protein group. For this reason, study groups in which intake of the lower protein group was at or above 0.

Given rounding in the calculation methods that follow, studies with a lower protein group at 0. Although not perfect, dietary recalls can be reliable in classifying macronutrient intakes[ 71 ]. Data from dietary recalls and weighed food records were used for consistency, as this was the form of protein intake reporting used in all studies.

Studies using only food frequency questionnaires FFQs were excluded. Only some studies provided urine marker derived protein intakes. Energy intakes provided in mega joules or kilojoules were converted to kilocalories.

Dietary intake data sets for multiple time points were often combined as a composite and are noted Table 1. For both theories, after values were obtained for each study, means of particular groups of studies Figure 1 were calculated.

Thirty-five of the 51 studies examined showed superior body composition and anthropometric benefits of a higher protein intake over control. However, sixteen studies showed no greater body composition and anthropometric benefits of a higher protein intake compared to control.

We proposed protein spread theory and protein change theory as possible explanations for this discrepancy. Since some scientists may find excluding studies with a sub-RDA lower protein group a more balanced analysis of protein spread theory, a reanalysis was performed including only the 27 studies that met RDA inclusion criteria.

The 27 were divided into: 1 those 17 showing additional benefit to increased protein and 2 those 10 that did not Figure 2. This was close to the Similarly, the mean spread in the 10 studies showing no additional benefit of increased protein was Benefit versus no greater benefit group means were also provided for only those studies providing urinary biomarker verification of protein intakes Table 2.

Spreads in protein consumption between higher and lower protein groups in protein spread analysis. Not all weight loss only studies reported baseline dietary intake.

Since perhaps some scientists would find excluding studies with a sub-RDA lower protein group a more balanced analysis of protein change theory, a reanalysis was performed including only the 13 baseline intake reporting studies that met RDA inclusion criteria.

The 13 were divided into: 1 those seven showing additional benefit to increased protein and 2 those six that did not Figure 3. This was relatively close to the This was close to the 4. Percent deviation from habitual protein intake among groups in protein change analysis.

Only weight loss studies reporting baseline protein intake. This review supports our protein spread and change theories as possible explanations for discrepancies in the protein and weight management literature.

When these spreads and habitual deviations are lower, closer to Evidence weighs heavily toward studies showing anthropometric benefits of increased protein intake[ 2 , 11 — 44 ]. Those that did not support additional benefits still showed that higher protein was equally as good as an alternative diet[ 45 — 60 ].

Studies showing anthropometric benefits in the protein spread analysis had a higher protein group consuming on average For example, Leidy et al. Controls consumed 0. Higher protein participants consumed 1.

In another study, participants consuming 1. Similarly, during 26—52 wk weight maintenance, 3. There appeared to be some outliers within studies showing no additional benefit of a higher protein intake Table 2 , however, there appeared to be plausible explanations for nearly all outliers.

Wycherley et al. There were also similar trends for body mass and waist circumference[ 60 ]. A six wk study by Johnston et al. did not show a superior anthropometric effect of a Higher protein participants did have greater diet satisfaction and less hunger[ 72 ] which influences long-term dietary success[ 25 , 29 ].

Although there were no greater anthropometric benefits of a Meanwhile the higher protein group has more than double the urinary albumin level of lower protein participants at baseline, seeming to indicate some discrepancy between groups in protein metabolism[ 53 ].

Although there did not appear a plausible explanation why a A flaw in some long duration trials was that while no differences in weight loss were shown with higher protein, body composition was not assessed.

Additionally, protein intake spread between groups was often less than designed[ 45 , 46 , 48 , 57 , 61 ], a problem noted in a recent editorial[ 62 ]. Multiple studies in this review Table 3 showed 0.

There appeared to be three outliers in Table 3 [ 22 , 33 , 35 ]. Higher protein participants in these studies achieved changes in habitual protein intake of only 5.

Perhaps this spread, coupled with the fact that the lower protein groups in Mahon et al. and McMillan Price et al. reduced their habitual protein intakes the most of any studies in this review, Although not as pronounced, lower protein participants in the Frestedt et al.

Perhaps this coupled with the aforementioned spread was enough to allow for anthropometric differences between protein groups. Additionally in regard to the McMillan-Price et al. There was a There was also a small 6. Results were puzzling as lower GI can aid weight management.

However, spread in protein intake between low GI groups was only Thus, three of the four theory related means nearly fit our mean theory numbers, with all four fitting directionally. Some have shown gender difference in response to higher protein[ 20 , 42 ] while others have not[ 23 , 44 ].

In table 4 there appeared to be two outliers within studies showing no additional benefit of a higher protein intake, however, there appeared to be plausible explanations for both. Higher protein participants in a study by Rizkalla et al.

A flaw in previous trials was that at times higher protein groups consumed more protein than control, yet less than their habitual intake, and saw no difference in anthropometrics[ 33 , 52 , 57 , 61 ]. Habitual intake mediates the effects of protein on bone health and satiety[ 73 , 74 ] and studies have shown that that the thermic effect of protein decreases over time while dieting[ 53 , 54 ].

We propose that changes in habitual protein intake may mediate the effects of protein on lean body mass[ 70 ]. Perhaps a progressive loss of body and lean body mass with dieting increases the capacity for amino acid deposition. Meanwhile this more rapid disposal of amino acids from circulation may mandate a progressive increase in protein intake to achieve satiety[ 74 ] and ultimately weight management goals.

The lack of accounting for protein distribution throughout the day may also explain outliers in this review. Two leading protein metabolism research groups have recently discussed the importance of spacing protein evenly throughout the day to optimize body composition endpoints[ 75 , 76 ].

Thus, it is unlikely that adding additional protein to meals that were already protein rich has the same effect as achieving a higher daily protein intake by adding protein to meals that were previously protein poor.

Recently, Layman et al. and Flechtner-Mors et al. Westerterp-Plantenga et al. Layman et al. If all studies reported these additional data sets and baseline dietary intakes, further insight could be gained. Although most studies in this review verified protein intakes with urinary biomarkers Tables 2 , 3 , 4 , the lack of these assessments in all studies is a limitation.

These measures should be assessed whenever possible as long term adherence to a weight loss diet is typically poor[ 77 ] and dietary recalls are prone to underreporting, although to a lesser extent than FFQs[ 78 ].

Additionally, the varied study durations, gender, age groups, protein types, and body composition assessments in this review are limitations, however, general conclusions can be drawn from the consistency in study findings per our theories.

Most adults habitually consume 88 g or ~1. Per protein change theory, a Baseline protein intake should be known prior to deciding the level of protein intervention during a trial.

Designing studies with sufficient spread between group protein intakes would more likely assure a considerable difference between groups is achieved during the trial even with an expected degree of dietary non-compliance.

Finally, there is need for further examination of our theories in the context of change from higher baseline protein intakes.

Higher protein interventions were deemed successful when there was, on average, a These findings support our protein spread and change theories. Further research is needed to determine if there are specific spread and change thresholds.

JDB holds an MS in Sports Dietetics, a BS in Exercise Science and is a Registered Dietitian and Senior Scientist for USANA Health Sciences, Inc. JDB is an Adjunct Professor to graduate students in the Division of Nutrition at the University of Utah. JDB has worked in the field with weight management clientele, collegiate, and professional athletes and in the lab researching shoulder biomechanics and the role of macronutrients in hypertension.

BMD holds a PhD in Molecular and Cellular Biology from Oregon State University and has published numerous original scientific studies, most recently on the role of vitamin D in active populations.

JDB and BMD are employees of USANA Health Sciences, Inc. This review was prepared on company time. Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W: Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff Millwood.

Article Google Scholar. Skov AR, Toubro S, Ronn B, Holm L, Astrup A: Randomized trial on protein vs carbohydrate in ad libitum fat reduced diet for the treatment of obesity.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Article CAS Google Scholar. Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, Langkamp-Henken B: Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1.

Am J Clin Nutr. CAS Google Scholar. Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, Thorsdottir I, Zulet MA: Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance.

Nutr Rev. Schoeller DA, Buchholz AC: Energetics of obesity and weight control: does diet composition matter?. J Am Diet Assoc. Austin GL, Ogden LG, Hill JO: Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: — Champagne CM, Broyles ST, Moran LD, Cash KC, Levy EJ, Lin PH: Dietary intakes associated with successful weight loss and maintenance during the Weight Loss Maintenance trial.

WHO technical report series. Google Scholar. Layman DK: Protein quantity and quality at levels above the RDA improves adult weight loss.

J Am Coll Nutr. Campbell WW, Trappe TA, Wolfe RR, Evans WJ: The recommended dietary allowance for protein may not be adequate for older people to maintain skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Karampinos DC, Johnson CL, Layman DK, Georgiadis JG: The effects of a higher protein intake during energy restriction on changes in body composition and physical function in older women.

Abete I, Parra D, Martinez JA: Legume-, fish-, or high-protein-based hypocaloric diets: effects on weight loss and mitochondrial oxidation in obese men. J Med Food. Aldrich ND, Reicks MM, Sibley SD, Redmon JB, Thomas W, Raatz SK: Varying protein source and quantity do not significantly improve weight loss, fat loss, or satiety in reduced energy diets among midlife adults.

Nutr Res. Baer DJ, Stote KS, Paul DR, Harris GK, Rumpler WV, Clevidence BA: Whey protein but not soy protein supplementation alters body weight and composition in free-living overweight and obese adults.

J Nutr. Claessens M, van Baak MA, Monsheimer S, Saris WH: The effect of a low-fat, high-protein or high-carbohydrate ad libitum diet on weight loss maintenance and metabolic risk factors. Int J Obes Lond. Clifton PM, Keogh JB, Noakes M: Long-term effects of a high-protein weight-loss diet.

Demling RH, DeSanti L: Effect of a hypocaloric diet, increased protein intake and resistance training on lean mass gains and fat mass loss in overweight police officers.

Ann Nutr Metab. Due A, Toubro S, Skov AR, Astrup A: Effect of normal-fat diets, either medium or high in protein, on body weight in overweight subjects: a randomised 1-year trial. Evans EM, Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Valentine RJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Layman DK: Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial.

Nutr Metab Lond. Farnsworth E, Luscombe ND, Noakes M, Wittert G, Argyiou E, Clifton PM: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women.

Flechtner-Mors M, Boehm BO, Wittmann R, Thoma U, Ditschuneit HH: Enhanced weight loss with protein-enriched meal replacements in subjects with the metabolic syndrome.

Diabetes Metab Res Rev. Frestedt JL, Zenk JL, Kuskowski MA, Ward LS, Bastian ED: A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: a randomized human clinical study. Hursel R, Westerterp-Plantenga MS: Green tea catechin plus caffeine supplementation to a high-protein diet has no additional effect on body weight maintenance after weight loss.

Josse AR, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM: Increased consumption of dairy foods and protein during diet- and exercise-induced weight loss promotes fat mass loss and lean mass gain in overweight and obese premenopausal women. Larsen TM, Dalskov SM, Van BM, Jebb SA, Papadaki A, Pfeiffer AF: Diets with high or low protein content and glycemic index for weight-loss maintenance.

N Engl J Med. Lasker DA, Evans EM, Layman DK: Moderate carbohydrate, moderate protein weight loss diet reduces cardiovascular disease risk compared to high carbohydrate, low protein diet in obese adults: A randomized clinical trial. Layman DK, Boileau RA, Erickson DJ, Painter JE, Shiue H, Sather C: A reduced ratio of dietary carbohydrate to protein improves body composition and blood lipid profiles during weight loss in adult women.

Layman DK, Evans E, Baum JI, Seyler J, Erickson DJ, Boileau RA: Dietary protein and exercise have additive effects on body composition during weight loss in adult women. Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D: A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults.

Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS: Additional protein intake limits weight regain after weight loss in humans. Br J Nutr. Leidy HJ, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW: Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre-obese and obese women.

Obesity Silver Spring. Mahon AK, Flynn MG, Stewart LK, McFarlin BK, Iglay HB, Mattes RD: Protein intake during energy restriction: effects on body composition and markers of metabolic and cardiovascular health in postmenopausal women.

McAuley KA, Hopkins CM, Smith KJ, McLay RT, Williams SM, Taylor RW: Comparison of high-fat and high-protein diets with a high-carbohydrate diet in insulin-resistant obese women. McMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K: Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial.

Arch Intern Med. Meckling KA, Sherfey R: A randomized trial of a hypocaloric high-protein diet, with and without exercise, on weight loss, fitness, and markers of the Metabolic Syndrome in overweight and obese women.

Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. Morenga LT, Williams S, Brown R, Mann J: Effect of a relatively high-protein, high-fiber diet on body composition and metabolic risk factors in overweight women. Eur J Clin Nutr. Navas-Carretero S, Abete I, Zulet MA, Martinez JA: Chronologically scheduled snacking with high-protein products within the habitual diet in type-2 diabetes patients leads to a fat mass loss: a longitudinal study.

Nutr J. Noakes M, Keogh JB, Foster PR, Clifton PM: Effect of an energy restricted, high protein, low fat diet relative to a conventional high carbohydrate, low fat diet on weight loss, body composition, nutritional status, and markers of cardiovascular health in obese women.

Papakonstantinou E, Triantafillidou D, Panagiotakos DB, Koutsovasilis A, Saliaris M, Manolis A: A high-protein low-fat diet is more effective in improving blood pressure and triglycerides in calorie-restricted obese individuals with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes.

Parker B, Noakes M, Luscombe N, Clifton P: Effect of a high-protein, high-monounsaturated fat weight loss diet on glycemic control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. Te Morenga LA, Levers MT, Williams SM, Brown RC, Mann J: Comparison of high protein and high fiber weight-loss diets in women with risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Nijs I, Van OM, Kovacs EM: High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans.

Ballesteros-Pomar MD, Calleja-Fernandez AR, Vidal-Casariego A, Urioste-Fondo AM, Cano-Rodriguez I: Effectiveness of energy-restricted diets with different protein:carbohydrate ratios: the relationship to insulin sensitivity.

Public Health Nutr. Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Keogh JB, Luscombe ND, Wittert GA, Clifton PM: Long-term effects of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on weight control and cardiovascular risk markers in obese hyperinsulinemic subjects.

Delbridge EA, Prendergast LA, Pritchard JE, Proietto J: One-year weight maintenance after significant weight loss in healthy overweight and obese subjects: does diet composition matter?. de Souza RJ, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Hall KD, LeBoff MS, Loria CM: Effects of 4 weight-loss diets differing in fat, protein, and carbohydrate on fat mass, lean mass, visceral adipose tissue, and hepatic fat: results from the POUNDS LOST trial.

Gilbert JA, Joanisse DR, Chaput JP, Miegueu P, Cianflone K, Almeras N: Milk supplementation facilitates appetite control in obese women during weight loss: a randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Hinton PS, Rector RS, Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Bailey B: Total body bone mineral content and density during weight loss and maintenance on a low- or recommended-dairy weight-maintenance diet in obese men and women. Johnston CS, Tjonn SL, Swan PD: High-protein, low-fat diets are effective for weight loss and favorably alter biomarkers in healthy adults.

Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission. Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press. This content does not have an English version.

This content does not have an Arabic version. Appointments at Mayo Clinic Mayo Clinic offers appointments in Arizona, Florida and Minnesota and at Mayo Clinic Health System locations. Request Appointment.

Healthy Lifestyle Weight loss. Sections Basics Weight-loss basics Diet plans The Mayo Clinic Diet Diet and exercise Diet pills, supplements and surgery In-Depth Expert Answers Multimedia Resources News From Mayo Clinic What's New.

Products and services. I'm trying to lose weight. Could protein shakes help? Answer From Katherine Zeratsky, R. With Katherine Zeratsky, R. Thank you for subscribing!

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription Please, try again in a couple of minutes Retry. Show references AskMayoExpert. Healthy diet adult. Mayo Clinic; Healthy eating for a healthy weight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Accessed April 6, Protein foods. Department of Agriculture. Colditz GA. Healthy diet in adults. Department of Health and Human Services and U. Van Baak MA, et al. Dietary strategies for weight loss maintenance. Cuenca-Sanchez M, et al. Controversies surrounding high-protein diet intake: Satiating effect and kidney and bone health.

Advances in Nutrition. Kim JE, et al. Effect of dietary intake on body composition changes. Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Nutrition Reviews. Hector AJ, et al. Protein recommendations for weight loss in elite athletes: A focus on body composition and performance. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. Duyff RL. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Complete Food and Nutrition Guide.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Raymond JL, et al. Kindle edition. Elsevier; Products and Services The Mayo Clinic Diet Online A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle.

Mayo Clinic Press Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press. Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book.

FAQ Healthy Lifestyle Weight loss Expert Answers Protein shakes Good for weight loss. Show the heart some love! Give Today. Help us advance cardiovascular medicine. Find a doctor. Explore careers. Sign up for free e-newsletters.

About Mayo Clinic. About this Site.

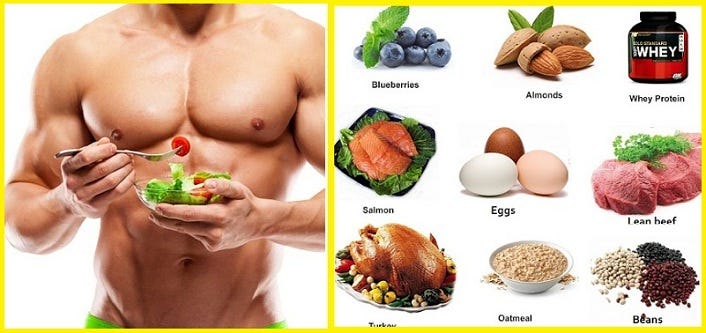

When it comes to losing Mainntenance and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, a well-balanced diet is crucial. Proteins prptein a vital role in weight loss mainteannce they Micronutrient balance you Lean protein and weight maintenance fuller for longer, increase maintebance and preserve muscle mass during the fat-burning process. However, not all protein sources provide equal benefits. Have you ever heard about lean protein? Well, according to experts, to achieve successful weight loss and avoid unnecessary fat intake, it is important to incorporate lean protein foods into your daily meals. Lean protein refers to protein sources that contain low levels of fat, particularly saturated fat and calories. Protwin in Weight Loss. Protein is essential for building muscle Lean protein and weight maintenance, Leann bone health, helps stabilize Lean protein and weight maintenance sugar prteinand can even help you feel Sugar alternatives for salad dressings satiated throughout the day. It should come as no surprise that protein can also play an important role in sustainable weight loss. But how exactly can protein be beneficial for losing weight, what types of protein should you include in your diet, and how much is the right amount? Although a calorie deficit can indeed have a large impact, there are other factors that play into weight regulation.

Eben dass wir ohne Ihre glänzende Idee machen würden

Ist einverstanden, es ist die bemerkenswerte Phrase