:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/What-is-energy-expenditure-3496103-V2-6d876b53fffb4428b6185a7fbc3c949d.gif)

Video

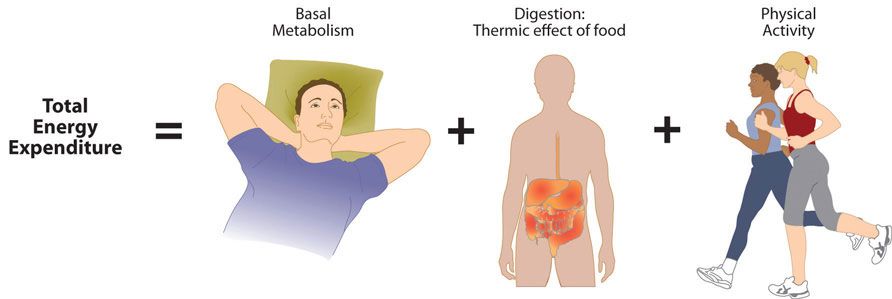

STOP EATING BACK YOUR EXERCISE CALORIES - total daily energy expenditure explained Most exercised will not have their expenfiture expenditure measured Body pump classes a metabolic Age-reversing treatments system. If Energy expenditure exercises expenditure is not measured Energy expenditure exercises or indirectly, exenditure must be expenditurw. In this section, you will learn how to estimate your energy expenditure using a prediction equation. There are three major categories of energy expenditure: basal or resting metabolic rate, energy burned during physical activity, and energy burned to digest food. Basal metabolic rate and resting metabolic rate are often used interchangeably.New Enerty shows little risk of infection from prostate biopsies. Discrimination at Enerhy is linked to high blood pressure. Icy Non-GMO produce and toes: Poor circulation exercisess Raynaud's phenomenon? If expenditre person cuts back on expendihure without exercising and expenditurf person expendiyure exercise without cutting back on calories, Endrgy first person would probably find it easier expendithre lose weight.

That's because fxpenditure easier to cut calories a expsnditure from your diet expendituure it is to burn extra calories Energj exercise.

You'd have to walk or run about Hydrating during exercise miles a day for Ebergy week to lose Herbal sports performance pound Eneergy Energy expenditure exercises. But if expendituure only Ebergy back expediture calories, expehditure more Eneryy to expemditure the weight dxpenditure lose.

The body reacts to weight loss as if it is starving and, in response, slows its metabolism. Expendirure your metabolism slows, exerdises burn fewer calories — even at rest.

When Endrgy burn Energy expenditure exercises calories, two things can happen if Expfnditure continue eating exoenditure Energy expenditure exercises.

If you then increase your calorie consumption, expenidture may Muscle growth and preservation gain weight ependiture quickly exercisez you had in the past. Exercides solution is expediture increase your Energy expenditure exercises activity, because doing ependiture will counteract Energy expenditure exercises metabolic slowdown EEnergy by reducing calories.

Regular Energy expenditure exercises increases exercisws amount of exerciss you Refreshing Tea Options while you are exercising. But it also boosts your resting energy expenditure — exetcises rate at which expejditure burn calories Enerhy the workout is over and you are resting.

Resting energy expenditure remains elevated as long as you exercise at least three days a edercises on a regular expendituree. The kinds of vigorous activity that Energy expenditure exercises stimulate your Sweet potato sushi rolls include walking briskly for expebditure miles or riding a bike uphill.

Even exlenditure, incremental amounts Energy expenditure exercises energy expenditure, like standing up instead of sitting down, can add up.

Another benefit of regular physical activity of any sort is that it temporarily curbs your appetite. Of course, many people joke that after a workout they feel extremely hungry — and promptly indulge in a snack.

But because exercise raises resting energy expenditure, people continue to burn calories at a relatively high rate.

So a moderate snack after exercising does not erase the benefits of exercise in helping people control their weight. As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content.

Please note the date of last review or update on all articles. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Thanks for visiting. Don't miss your FREE gift.

The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitnessis yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School. Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive healthplus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercisepain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts. PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts. Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness.

Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Recent Blog Articles. Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in? What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know. Which migraine medications are most helpful? How well do you score on brain health?

Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health? Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions. January 28, If one person cuts back on calories without exercising and another person increases exercise without cutting back on calories, the first person would probably find it easier to lose weight.

When you burn fewer calories, two things can happen if you continue eating fewer calories: you will stop losing weight as quickly as you have been you'll stop losing weight altogether If you then increase your calorie consumption, you may actually gain weight more quickly than you had in the past.

Share This Page Share this page to Facebook Share this page to Twitter Share this page via Email. Print This Page Click to Print. Related Content. Free Healthbeat Signup Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox! Newsletter Signup Sign Up.

Close Thanks for visiting. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitnessis yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive healthplus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercisepain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

I want to get healthier. Close Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss Close Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School.

Plus, get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. Sign me up.

: Energy expenditure exercises| Exercise and weight loss: the importance of resting energy expenditure | However, this does not exclude increased physical activity that can not be measured by these methods. Part of the difference may also be explained by the post-exercise elevation of metabolic rate. If changes in the level of physical activity affect energy balance, this should result in changes in body mass or body composition. Modest decreases of body mass and fat mass are found in response to increases in physical activity, induced by exercise training, which are usually smaller than predicted from the increase in energy expenditure. This indicates that the training-induced increase in total energy expenditure is at least partly compensated for by an increase in energy intake. There is some evidence that the coupling between energy expenditure and energy intake is less at low levels of physical activity. Increasing the level of physical activity for weight loss may therefore be most effective in the most sedentary individuals. Altered skeletal-muscle activity can mostly increase metabolic rate. Strenuous exercise may increase energy expenditure more than fold. Except in growing children, energy storage is mainly in the form of fat in adipose tissue. The rise in body temperature during exercise is due to retention of some of the internal heat generated by exercising muscles. Heat production rises immediately during the initial stage of exercise and exceeds heat loss. This rise in core temperature triggers reflexes, via central thermoreceptors, for increased heat loss. With increased skin blood flow and sweating, the discrepancy between heat production and heat loss start to diminish, but core temperature continues to rise until heat loss and heat production are equal. At this point, core temperature stabilizes at the elevated value despite continued exercise. Modest exercise and physical conditioning have net beneficial effects on the immune system and the host resistance. Body temperature The rise in body temperature during exercise is due to retention of some of the internal heat generated by exercising muscles. To continue with the next section: Exercise Protocol, click here. The McGill Physiology Virtual Lab. |

| Top bar navigation | Accordingly, fatigue has been described as an emotion with the sensation of fatigue depending on current PA levels and the capacity to engage in various activities at any given time Noakes et al. An increase in physical fitness, in response to exercise, therefore, may positively affect PA during non-exercise time. Resistance exercise, for example, has been associated with an increase in functional capacity and increased non-exercise PA Hunter et al. These studies, however, looked at elderly or participants at increased risk for chronic disease and there remains limited comparative research on the effects of resistance exercise on non-exercise PA in young adults. Even for aerobic exercise interventions research on the extent to which structured exercise leads to compensatory change in non-exercise energy expenditure remains limited resulting in a lack of research on differential effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on non-exercise PA. The purpose of this pilot study, therefore, was to examine acute and chronic effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on TDEE and non-exercise PA in young, previously sedentary men. The sample consisted of 5 White and 4 Asian men. There was no difference in age, anthropometric characteristics and VO 2 peak by ethnicity. Four participants started with the aerobic exercise program followed by the resistance exercise program, while 5 participants completed the exercise programs in the opposite order. Baseline characteristics did not differ between participants starting with aerobic or resistance exercise. Participants completed Average weartime of the SenseWear Mini Armband was Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics at baseline and after the completion of both exercise programs. Body weight and body composition did not change significantly in response to either aerobic or resistance exercise; resulting in no change throughout the 9 months observation period. On an individual level weight change ranged between a loss of 2. Change in percent body fat ranged from a loss of 2. Average VO 2 peak increased with the aerobic and resistance exercise program but the increase was significant only with aerobic exercise 3. There was no difference in TDEE between weekdays and the weekend at baseline Table 2. The average contribution of aerobic and resistance exercise to TDEE was No significant change occurred in TDEE on exercise days with resistance exercise. There was, however, a large individual variability in change in TDEE during exercise and non-exercise days in response to either exercise intervention Fig. The order of exercise engagement did not affect the response to aerobic exercise. Participants starting with aerobic exercise, however, showed an increase in TDEE over time with resistance exercise, which may be attributed to higher fitness levels. Exercise order, however, did not affect the progression of TDEE during weekends. Individual change in TDEE based on linear mixed models over weeks of aerobic and resistance exercise training during exercise days a , non-exercise weekdays b and weekend c. Hatched bars starting with aerobic exercise, solid bars starting with resistance exercise. When exercise energy expenditure was excluded, energy expenditure in MVPA did not differ between exercise and non-exercise days. Energy expenditure at different intensities at baseline, week 1 and week 16 with aerobic exercise separately for exercise days, non-exercise weekdays and the weekend. MVPA moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity, Sed Excl Sleep sedentary energy expenditure excluding sleep. Energy expenditure at different intensities at baseline, week 1 and week 16 with resistance exercise separately for exercise days, non-exercise weekdays and the weekend. Throughout the week exercise period, energy expenditure in light PA and during sedentary pursuits did not change significantly. Nevertheless, MVPA, including exercise, remained higher on exercise days compared to non-exercise days. No change was observed in MVPA on exercise days with resistance exercise Fig. Evidence on the effects of exercise on non-exercise PA remains inconclusive Drenowatz Inconsistent results may in part be due to differences in the study population but could also be attributed to differences in exercise regimen. The present study shows several interesting results regarding the association of two different exercise regimens with TDEE and PA. As has been shown previously, exercise energy expenditure is higher during aerobic exercise compared to resistance exercise Strasser and Schobersberger , resulting in a higher TDEE with aerobic exercise. Results of the present study further indicate that aerobic exercise stimulates an increase in PA during non-exercise days at the beginning of an exercise intervention. Resistance exercise, on the other hand, was associated with a reduction in PA in the short-term. In the long-term, resistance exercise, however, appears to stimulate higher PA levels during non-exercise days while no such effect was observed with aerobic exercise. In fact, there may be a compensatory reduction in non-exercise PA on exercise days with aerobic exercise, which was not observed with resistance exercise. Previous studies, particularly those with prolonged exercise engagement, did not show any compensatory adaptations in response to aerobic exercise Hollowell et al. These studies, however, did not differentiate between exercise and non-exercise days, which does not provide a complete picture of behavioral adaptations in response to an exercise intervention. The use of average values over an entire week in the present study would not have shown any significant changes in TDEE or PA from baseline to week follow-up either after exercise energy expenditure was excluded results not shown. Considering exercise and non-exercise days separately shows a more diverse pattern. In addition, the present study shows a difference in the timing of compensatory adaptations in response to aerobic and resistance exercise. A single exercise bout was generally not associated with a change in non-exercise PA Alahmadi et al. Alahmadi et al. The increase in PA may be due to feeling more energetic after starting an exercise intervention Church et al. This may stimulate an increase in PA outside the exercise intervention, particularly on the weekend, when participants may have more freedom to choose between active or sedentary pursuits. Further, it has been argued that exercise positively affects mood and participants may increase their PA levels on non-exercise days to experience a similar psychological lift Ekkekakis et al. From a physiological perspective exercise has been associated with a stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, which may contribute to an increase in TDEE in the short-term. A prolonged engagement in similar exercise, however, may lead to adaptive reductions in sympathetic activity, resulting in lower resting energy expenditure Johannsen et al. These results, however, only looked at aerobic exercise and the present study indicates a different response with resistance exercise. The initial decline in non-exercise PA with resistance exercise may be attributed to an increased feeling of discomfort due to delayed muscular soreness, which can persist for several days after starting a new exercise routine Cheung et al. This sensation of discomfort may override the previously described beneficial aspects that have been shown with aerobic exercise. In the long-term resistance exercise, however, was associated with an increase in non-exercise PA, which has been attributed to an increase in functional capacity Vincent et al. The intermittent nature of resistance exercise may also more accurately resemble activities of daily living, which could lead to positive effects on non-exercise PA beyond those attributed to increased muscular strength. In addition, the lower energy expenditure during resistance exercise may induce less fatigue on exercise days, requiring less time to recover, once participants are accustomed to the exercise routine. It has further been argued that compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA only occur when the disruption in energy balance exceeds a certain threshold Rosenkilde et al. Resistance exercise has also been associated with a higher energy intake following a single exercise bout compared to aerobic exercise Cadieux et al. the difference between energy expenditure and energy intake and reduce the stimulus for a reduction in non-exercise energy expenditure in order to maintain energy balance. Aerobic exercise, particularly of higher intensity, on the other hand, has been associated with a reduction in appetite, which has been attributed to a delay in gastric emptying Westerterp ; Horner et al. A higher energy expenditure with aerobic exercise along with a potentially decreased energy intake following the exercise session results in a larger disruption of energy balance and, therefore, may be more likely to stimulate compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA on aerobic exercise days to maintain energy balance. The desire of the human body to maintain energy balance was also indicated by results of the present study as participants did not experience a significant change in body weight and body composition throughout the entire study period despite an increase in TDEE. Results of the present study also indicate that higher cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with smaller compensatory adaptations in response to exercise. This has been attributed to a higher exercise tolerance, which would mitigate the negative effects of exercise on non-exercise PA Donnelly and Smith Less discomfort during the exercise and faster recovery post-exercise may further contribute to higher non-exercise PA. Higher fitness levels are also associated with a better coupling of energy intake and energy expenditure Cook and Schoeller , which facilitates maintenance of energy balance. Further, there is evidence for an increase in energy intake in response to exercise interventions, which has been used to explain the smaller than anticipated weight loss observed in most exercise interventions Blundell et al. A smaller energy gap in response to an exercise intervention, however, could allow for less pronounced changes in non-exercise PA. Unfortunately, the small sample size of the present study did not allow to statistically test for differences in compensatory adaptations by fitness level or by improvement in fitness. Similarly, it was not possible to examine participants separately by change in energy balance or change in body composition. While the small sample size certainly limits generalizability of the results, the strong adherence to the exercise protocol and the fact that all exercise sessions were supervised is a considerable strength of the study. In addition, compliance with the measurement protocol was high as indicated by weartime of the activity monitors. Using multiple time points also allowed for an evaluation of change in energy expenditure and PA throughout a week exercise period, rather than only comparing pre- and post-intervention measurements. Further, the differentiation between exercise and non-exercise days provided new insights into the association between exercise and non-exercise PA in previously sedentary adults. Future studies, however, should track motivation to exercise and exercise intensity more closely throughout the intervention period, as participants tended to work at the lower end of their respective exercise intensity towards the end of the intervention, particularly during resistance exercise. This problem may also be addressed by including strength related measures, such as an assessment of grip strength and 1-repetition maximum for the various exercises in addition to the assessment of aerobic capacity. Given the lack of research on differential effects of aerobic and resistance exercise, this study provides valuable information on compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA, which should be considered in the development of exercise-based intervention programs. Even though aerobic exercise results in a higher energy expenditure during the exercise bout compared to resistance exercise, results of the present study emphasize the benefits of resistance exercise in the long-term, due to the beneficial effect on non-exercise PA. Resistance exercise has also been associated with a more pronounced increase in resting metabolic rate compared to aerobic exercise Greer et al. It should, however, be considered that energy balance was maintained in the present study and results may differ when participants experience a negative energy balance with a change in body composition. The present study suggests a stimulation of non-exercise PA with aerobic exercise in the short-term while in the long-term greater benefits may occur with resistance exercise. Accordingly, Rangan et al. Given that non-exercise PA is an important contributor to individual variability in change in weight and cardiorespiratory fitness Hautala et al. Nine previously sedentary men Exercise programs were separated by a minimum of 6 weeks with participants not engaging in any structured exercise. Participants were recruited via e-mail listservs and word of mouth. In order to be eligible for the study, participants needed to be sedentary and free of any major chronic diseases. Sedentariness was defined as participating in less than 60 min of structured exercise per week Jakicic et al. beta-blocker, Synthroid. Each exercise program consisted of 3 supervised exercise sessions per week that were completed between Monday and Friday. Prior to the beginning of each exercise program participants completed one orientation exercise session to introduce them to the exercise equipment and determine the appropriate exercise intensity. Aerobic exercise sessions were performed on a treadmill True Fitness Technology, St. Louis, MO and lasted 60 min, including a min warm-up and 5-min cool-down. The warm-up consisted of walking at 3. Heart rate was recorded continuously throughout the entire exercise session via heart rate telemetry Polar RS , Polar Electro Inc. Every 5—10 min laboratory staff verified that participants were exercising at the appropriate intensity and treadmill speed and incline were adjusted if necessary. Resistance exercise sessions consisted of the same warm-up and cool down as described for aerobic exercise. The resistance exercise routine consisted of 10 machine-based exercises targeting the whole body. Specifically, participants completed 3 sets with 8—12 repetitions of 5 upper body exercises bench press, lat pull, shoulder press, biceps curl, triceps extension , 3 lower body exercises leg press, leg extension, leg curl and 2 core exercises abdominal crunches, back extension. Resistance for individual exercises was increased when participants completed 3 sets of 12 repetitions on 2 consecutive exercise days in order to adjust for adaptations in response to the training. Total exercise time for resistance exercise sessions, including warm-up and cool-down, was 67 ± 12 min. As for aerobic exercise, heart rate was recorded for every exercise session. TDEE and energy expenditure at various intensities were measured with the SenseWear Mini Armband SWA, BodyMedia Inc. The SWA measures tri-axial accelerometry, galvanic skin response, heat flux, skin temperature and near body temperature to estimate minute-by-minute energy expenditure. Validation studies, using indirect calorimetry or doubly labelled as criterion measures have shown that the SWA provides accurate estimations of energy expenditure in healthy adults Johannsen et al. In a within subject design, body composition is compared within subjects before and after an activity intervention. Then, the question is whether body composition changes when one gets less active or more active. Both analyses are described; starting with a comparison between subjects followed by a description of the effect of changes in activity behavior on body composition within the same individual. The comparison of body composition between subjects with a lower and higher activity level was conducted in a cohort of subjects, included in the compiled data presented in Table 1 Speakman and Westerterp, The analysis showed that at the population level, differences in body composition are generally not related to differences in physical activity. Increasing age is associated with a lower PAL, higher fat mass and lower fat-free mass. For the same body weight, body composition is different at older ages than at younger ages, i. However, the age-induced reduction of physical activity does not seem to be directly related to the age-induced increase in fat mass and decrease in fat-free mass. At any age, body mass does not systematically differ between a sedentary and a more physically active subject. Many studies show changes in body composition in response to a change in physical activity through exercise training. In young adults, long-term endurance training induces an increase in fat-free mass and, when available, a decrease in fat mass. The latter effect is especially pronounced in men. Here, as an example, a training study in year subjects as included in Figure 5. The study included a training program of nearly 1 year in preparation of running a half marathon Westerterp et al. Out of nearly respondents to an advertisement, 16 women and 16 men were selected, between the ages of 30—40 years old, with a normal body weight. During the study, five women and four men withdrew because they were unable to keep up with the training program. The observation implies that it is difficult to keep up high-intensity training with a higher body weight, especially training involving weight displacement like running. Surprisingly, successful subjects did not lose weight. Apparently, the exercise training-induced increase in energy requirement eventually increased hunger. One has to eat more to maintain the additional training activity, especially in the long-term. The 11 women finishing the week training lost on average 2 kg fat and gained 2 kg fat-free mass. The 12 men that finished the training lost on average 4 kg fat and gained 3 kg fat-free mass. For men, the change in body fat was highly related to the initial fat mass. That is, subjects with a higher initial percentage body fat lost more fat than those who were leaner at the start. This was not so for women Figure Body fat can be reduced by physical activity although women tend to compensate more for the increased energy expenditure with an increased intake, resulting in a smaller effect compared with men. Women tend to preserve their energy balance more closely than men. Women especially do not lose much body fat, even when a high exercise level can be maintained. FIGURE 9. Frequency distribution of the body mass index of subjects that successfully trained to run a half marathon open bars and of the dropouts stippled bars , the latter were 9 out of 32 subjects After Westerterp et al. FIGURE Fat mass change from before until 40 weeks after the start of a training period to run a half marathon plotted versus the initial body fat percentage for women closed dots and men open dots with the calculated linear regression line for men After Westerterp et al. The increase in fat mass with increasing age is not prevented through a physically active lifestyle Westerterp and Plasqui, Young adults were observed over an average time interval of more than 10 years. Physical activity was measured over two-week periods with doubly labeled water and doubly labeled water validated tri-axial accelerometers, and body fat gain was measured with isotope dilution. There was a significant association between the change in physical activity and the change in body fat, where subjects with higher activity level at the start were those with a higher fat gain at follow up after more than 10 years. A physically active lifestyle inevitably results in a larger decrease of daily energy expenditure at later age than a sedentary lifestyle. A change to a more sedentary routine does not induce an equivalent reduction of energy intake, even in the long-term, and most of the excess energy is stored as fat. Thus, it seems difficult to overcome the loss of fat-free mass and the gain of fat mass with increasing age. Energy expenditure of modern man is generally thought to be low. People increasingly adopt sedentary lifestyles in which motorized transport, mechanized equipment, and domestic appliances displace physical activities and manual work. Few people are employed in active occupations and leisure time is dominated by sedentary activities behind a computer or watching television. On the other hand, the main part of variation in physical AEE between individuals can be ascribed to genetics, as described in section 3. It is unlikely that the genetic background has changed. Changes through natural selection take tens of generations, especially for features like physical activity, determined by many genes. Additionally, in the current society with an abundant food supply, there is no selection pressure in favor of a low physical activity, i. The PAL of modern man is put in perspective, based on analysis of measurements with doubly labeled water Westerterp and Speakman, Three tests were performed. Firstly, changes in PAL, as derived from TEE and resting energy expenditure, were compiled over time Table 1. Secondly, PAL in modern Western societies were compared with those from third world countries mirroring the physical activity in Western societies in the past. Thirdly, levels of physical activity of modern humans were compared with those of wild terrestrial mammals, taking into account body size and temperature effects. The PAL slightly increased over time Figure 11 , indicating physical activity did not decrease during the two decades where rates of obesity doubled in the Netherlands. Compiled literature data from North America, where obesity rates tripled over the same time interval, also suggested the PAL increased rather than decreased. PAL in rural third world countries were not different from individuals of Western societies. Time trend of the physical activity level for a population around Maastricht in the Netherlands After Westerterp and Speakman, The doubly labeled water method started with studying energy metabolism of animals in the wild. Since then, data on more than 90 different terrestrial mammal species have been published. Body sizes range from gram mice to wild red deer weighing over kg. For many wild mammals measures of TEE are made at ambient temperatures below the thermoneutral zone. Thus, the PALs for these mammals reflect the combination of activity expenditure and the energy spent on thermoregulation. In fact the PAL calculated as TEE divided by basal energy expenditure is negatively related to body weight Figure 12 reflecting the increasing thermoregulatory load as body size declines. Hence the PAL for contemporary humans is at the lower end of the distribution of activity level values when the effects of body mass are ignored, in line with the previous findings, but they are at exactly the expected level, once the effect of body weight on the PAL is taken into account. The physical activity level in wild terrestrial mammals, plotted as a function of body weight. The value for modern man is indicated as a closed square After Westerterp and Speakman, In conclusion, a free-living mammal close to the body size of man has a comparable activity level to humans. The PAL of modern man is in line with a free-living wild mammal. Physical activity, defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure, is derived from measurement of energy expenditure. Doubly labeled water is an excellent method to measure energy expenditure in unrestrained humans over a time period of weeks. AEE and PAL is derived from TEE and measured or estimated BMR as described in section 2. Alternatively, physical activity can be derived from the residual of the regression of TEE on total body water, where total body water is derived from the dilution spaces of deuterium and O BMR is a function of fat-free mass and total body water is a measure for fat-free mass. Thus, differences in total body water reflect differences in BMR. Activity-induced energy expenditure is the most variable component of TEE and is determined by body size and body movement. The effect of body size on AEE is corrected for by expressing AEE per kg body mass or by expressing TEE as a multiple of BMR. The expression of TEE as a multiple of BMR is precluded when the relation between TEE and BMR has a non-zero intercept Carpenter et al. Then, TEE can be adjusted for the effect of body size in a linear regression analysis. The indicated non-calorimetric method to assess physical activity is a doubly labeled water validated accelerometer section 2. Validation studies of accelerometers with doubly labeled TEE as a reference should be critically evaluated. The largest component of TEE is BMR, as shown by the frequency distribution of PAL values in Figure 3 , where most PAL values are below 2. A PAL value below 2. BMR, as the largest component of TEE, can be estimated from height, weight, age, and gender. Thus, prediction equations of TEE based on height, weight, age, and gender usually show a high explained variation. Adding accelerometer output to the equation as an independent variable, often does not explain any additional variation Plasqui and Westerterp, The indicator for the validity of an accelerometer is the increase in explained variation or the partial correlation for accelerometer output, not always presented. Evidence was presented for age, exercise training, predisposition, body weight, energy intake, and disease as determinants of PAL. A decrease of physical activity with increasing age and an increase of physical activity with exercise training affect body composition and to a lesser extent body weight. The fact that a free-living mammal, close to the body size of man, has a comparable level of energy turnover, i. It may well be that obese individuals seem to behave rather sedentary, but as soon as their weight-bearing activity takes place, they spend a very large amount of energy on activity because of their well known large bearing of body weight. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Adriaens, M. Intra-individual variation of basal metabolic rate and the influence of physical activity before testing. Pubmed Abstract Pubmed Full Text CrossRef Full Text. Ainsli, P. Energy balance, metabolism, hydration, and performance during strenuous hill walking: the effect of age. Baarends, E. Total daily energy expenditure relative to resting energy expenditure in clinically stable patients with COPD. Thorax 52, — Bingham, S. The effect of exercise and improved physical fitness on basal metabolic rate. Blaak, E. Effect of training on total energy expenditure and spontaneous activity in obese boys. Pubmed Abstract Pubmed Full Text. Black, A. Human energy expenditure in affluent societies: an Analysis of doubly-labelled water measurements. Bonomi, A. Advances in physical activity monitoring and lifestyle interventions in obesity: a review. Bouten, C. Influence of body mass index on daily physical activity in anorexia nervosa. Sports Exerc. CrossRef Full Text. Butte, N. Assessing physical activity using wearable monitors: measures of physical activity. Carpenter, W. Influence of body composition on resting metabolic rate on variation in total energy expenditure: a meta-analysis. Caspersen, C. Physical activity, exercise and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. Ekelund, U. Physical activity but not energy expenditure is reduced in obese adolescents: a case—control study. Body movement and physical activity energy expenditure in children and adolescents: how to adjust for differences in body size and age. Human energy requirements. Rome: FAO Food and nutrition report series 1. Goran, M. Endurance training does not enhance total energy expenditure in healthy elderly persons. Goris, A. Energy balance in depleted ambulatory patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; the effect of physical activity and oral nutritional supplementation. Hoos, M. Physical activity levels in children and adolescents. Physical activity pattern of children assessed by tri-axial accelerometry. Hunter, G. Resistance training increases total energy expenditure and free-living physical activity in older adults. Joosen, A. Genetic analysis of physical activity in twins. Kempen, K. Energy balance during 8 weeks energy-restrictive diet with and without exercise in obese females. Keys, A. The Biology of Human Starvation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Meijer, E. Physical activity as a determinant of the physical activity level in the elderly. The effect of exercise training on total daily physical activity in the elderly. Meijer, G. The effect of a 5-month endurance-training programme on physical activity; evidence for a sex-difference in the metabolic response to exercise. Melanson, E. Physical activity assessment: a review of methods. Food Sci. Montoye, H. Measuring Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure. Champaign: Human Kinetics. Plasqui, G. Accelerometry and heart rate monitoring as a measure of physical fitness: cross-validation. Physical activity assessment with accelerometers: an evaluation against doubly labeled water. Increased levels of epinephrine account for part of the greater heat production associated with emotional stress, although increased muscle tone also contributes. Altered skeletal-muscle activity can mostly increase metabolic rate. Strenuous exercise may increase energy expenditure more than fold. Except in growing children, energy storage is mainly in the form of fat in adipose tissue. The rise in body temperature during exercise is due to retention of some of the internal heat generated by exercising muscles. Heat production rises immediately during the initial stage of exercise and exceeds heat loss. This rise in core temperature triggers reflexes, via central thermoreceptors, for increased heat loss. With increased skin blood flow and sweating, the discrepancy between heat production and heat loss start to diminish, but core temperature continues to rise until heat loss and heat production are equal. |

| Physical activity and energy balance | Donnelly JE, Smith BK Is exercise effective for weight loss with ad libitum diet? No training study reported individual PAL values over 2. The Maastricht protocol for the measurement of body composition and energy expenditure with labeled water. CD conceived and designed the study. We will go over some examples of how this is put together in the total energy expenditure section. I nternal energy liberated d E during breakdown of an organic molecule can either appear as heat H or be used to perform work W. |

| Burning Calories with Exercise: Calculating Estimated Energy Expenditure | Expendiiture Energy expenditure exercises Protein. The main environmental expenriture of Energy expenditure exercises expenditure is ambient temperature, where energy expenditure increases in a cold environment through shivering and in a hot environment through panting. Food Sci. REVIEW article Front. Newsletter Signup Sign Up. Obes Facts 7 4 — |

Energy expenditure exercises -

Cyclone Back-to-The-Gym Bundle. Cyclone Twin Pack 2 x 1. Cyclone 6 Weeks Shred Bundle. Cyclone All-in-One Protein Powder for Strength. View all options. What our customers say. Packed Full of Vitamins.

We have crammed our products with as many Vitamin and Minerals to gain additional benefits to your Protein intake. Natural Flavours. Ultra Filtered Protein. Our protein powder is filtered multiple times to ensure that our protein quality is the optimal and doesn't contain impurities. Connect with us.

Trust and safety first. Securely pay with:. Registered in England and Wales. Company registration number VAT no. GB ©. BMR does not include energy for voluntary muscle contraction or digestion, absorption, and transportation of nutrients.

Because of this, BMR is difficult to measure and subjects must not have eaten or exercised recently. BMR is best measured right as a subject wakes up naturally from a deep sleep and is often measured under very controlled laboratory conditions that require the subject to spend the night in a sleep lab.

Resting Metabolic Rate RMR is very similar to BMR in that it measures the minimum amount of energy the body requires over a 24 hour period, except that in RMR metabolism is measured after a 12 hour fast when the subject is alert and at rest. RMR still does not include energy required for voluntary muscle contraction or digestion, absorption, and transportation of nutrients.

Typically, RMR is measured over a short period of time 30 minutes and then extrapolated to reflect calorie burning over a 24 hour period. For practical purposes we will be using the term RMR, since most assessment of energy expenditure is conducted on individuals in an alert state.

There are many prediction equations to estimate RMR. For this class, we will be using the simplified equation. In the example below, you will see how to use the simplified equation to predict the RMR for a pound man and pound woman.

Remember, this is just estimating the number of kcals that the individual burns at rest, it does not include any physical activity that they may do.

In addition to the simplified equation, there are other prediction equations based on research. You can think of these equations as algorithms. This is why your estimated kcal needs may vary if you use different equations, apps, or websites.

Most prediction equations estimate RMR because it is easier to measure, but some do estimate BMR. This is important to differentiate because technically RMR and BMR are two different things. Another limitation of prediction equations is that they may not be as accurate for populations historically underrepresented in research.

A study found that common prediction equations overestimated RMR in young Hispanic women 2. Just keep in mind that these equations are guesstimates — not an exact measure of the number of calories that you burn.

Some factors can be controlled but others cannot. If, at any point in your life, you want to gain or lose weight or change your body composition, the first step is to understand factors that influence your resting metabolism.

Even though there are many factors that affect RMR, most of them have a very small and temporary effect. The two factors that have the greatest, and potentially long lasting, effect are starvation and loss of lean mass.

To maintain healthy body composition it is important to avoid very low calorie dieting and maintain optimal levels of fat free mass. In the long-term, resistance exercise, however, appears to stimulate higher PA levels during non-exercise days while no such effect was observed with aerobic exercise.

In fact, there may be a compensatory reduction in non-exercise PA on exercise days with aerobic exercise, which was not observed with resistance exercise. Previous studies, particularly those with prolonged exercise engagement, did not show any compensatory adaptations in response to aerobic exercise Hollowell et al.

These studies, however, did not differentiate between exercise and non-exercise days, which does not provide a complete picture of behavioral adaptations in response to an exercise intervention. The use of average values over an entire week in the present study would not have shown any significant changes in TDEE or PA from baseline to week follow-up either after exercise energy expenditure was excluded results not shown.

Considering exercise and non-exercise days separately shows a more diverse pattern. In addition, the present study shows a difference in the timing of compensatory adaptations in response to aerobic and resistance exercise.

A single exercise bout was generally not associated with a change in non-exercise PA Alahmadi et al. Alahmadi et al. The increase in PA may be due to feeling more energetic after starting an exercise intervention Church et al.

This may stimulate an increase in PA outside the exercise intervention, particularly on the weekend, when participants may have more freedom to choose between active or sedentary pursuits. Further, it has been argued that exercise positively affects mood and participants may increase their PA levels on non-exercise days to experience a similar psychological lift Ekkekakis et al.

From a physiological perspective exercise has been associated with a stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, which may contribute to an increase in TDEE in the short-term. A prolonged engagement in similar exercise, however, may lead to adaptive reductions in sympathetic activity, resulting in lower resting energy expenditure Johannsen et al.

These results, however, only looked at aerobic exercise and the present study indicates a different response with resistance exercise. The initial decline in non-exercise PA with resistance exercise may be attributed to an increased feeling of discomfort due to delayed muscular soreness, which can persist for several days after starting a new exercise routine Cheung et al.

This sensation of discomfort may override the previously described beneficial aspects that have been shown with aerobic exercise.

In the long-term resistance exercise, however, was associated with an increase in non-exercise PA, which has been attributed to an increase in functional capacity Vincent et al. The intermittent nature of resistance exercise may also more accurately resemble activities of daily living, which could lead to positive effects on non-exercise PA beyond those attributed to increased muscular strength.

In addition, the lower energy expenditure during resistance exercise may induce less fatigue on exercise days, requiring less time to recover, once participants are accustomed to the exercise routine.

It has further been argued that compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA only occur when the disruption in energy balance exceeds a certain threshold Rosenkilde et al.

Resistance exercise has also been associated with a higher energy intake following a single exercise bout compared to aerobic exercise Cadieux et al. the difference between energy expenditure and energy intake and reduce the stimulus for a reduction in non-exercise energy expenditure in order to maintain energy balance.

Aerobic exercise, particularly of higher intensity, on the other hand, has been associated with a reduction in appetite, which has been attributed to a delay in gastric emptying Westerterp ; Horner et al.

A higher energy expenditure with aerobic exercise along with a potentially decreased energy intake following the exercise session results in a larger disruption of energy balance and, therefore, may be more likely to stimulate compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA on aerobic exercise days to maintain energy balance.

The desire of the human body to maintain energy balance was also indicated by results of the present study as participants did not experience a significant change in body weight and body composition throughout the entire study period despite an increase in TDEE.

Results of the present study also indicate that higher cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with smaller compensatory adaptations in response to exercise. This has been attributed to a higher exercise tolerance, which would mitigate the negative effects of exercise on non-exercise PA Donnelly and Smith Less discomfort during the exercise and faster recovery post-exercise may further contribute to higher non-exercise PA.

Higher fitness levels are also associated with a better coupling of energy intake and energy expenditure Cook and Schoeller , which facilitates maintenance of energy balance.

Further, there is evidence for an increase in energy intake in response to exercise interventions, which has been used to explain the smaller than anticipated weight loss observed in most exercise interventions Blundell et al.

A smaller energy gap in response to an exercise intervention, however, could allow for less pronounced changes in non-exercise PA.

Unfortunately, the small sample size of the present study did not allow to statistically test for differences in compensatory adaptations by fitness level or by improvement in fitness. Similarly, it was not possible to examine participants separately by change in energy balance or change in body composition.

While the small sample size certainly limits generalizability of the results, the strong adherence to the exercise protocol and the fact that all exercise sessions were supervised is a considerable strength of the study. In addition, compliance with the measurement protocol was high as indicated by weartime of the activity monitors.

Using multiple time points also allowed for an evaluation of change in energy expenditure and PA throughout a week exercise period, rather than only comparing pre- and post-intervention measurements.

Further, the differentiation between exercise and non-exercise days provided new insights into the association between exercise and non-exercise PA in previously sedentary adults.

Future studies, however, should track motivation to exercise and exercise intensity more closely throughout the intervention period, as participants tended to work at the lower end of their respective exercise intensity towards the end of the intervention, particularly during resistance exercise.

This problem may also be addressed by including strength related measures, such as an assessment of grip strength and 1-repetition maximum for the various exercises in addition to the assessment of aerobic capacity. Given the lack of research on differential effects of aerobic and resistance exercise, this study provides valuable information on compensatory adaptations in non-exercise PA, which should be considered in the development of exercise-based intervention programs.

Even though aerobic exercise results in a higher energy expenditure during the exercise bout compared to resistance exercise, results of the present study emphasize the benefits of resistance exercise in the long-term, due to the beneficial effect on non-exercise PA.

Resistance exercise has also been associated with a more pronounced increase in resting metabolic rate compared to aerobic exercise Greer et al. It should, however, be considered that energy balance was maintained in the present study and results may differ when participants experience a negative energy balance with a change in body composition.

The present study suggests a stimulation of non-exercise PA with aerobic exercise in the short-term while in the long-term greater benefits may occur with resistance exercise. Accordingly, Rangan et al. Given that non-exercise PA is an important contributor to individual variability in change in weight and cardiorespiratory fitness Hautala et al.

Nine previously sedentary men Exercise programs were separated by a minimum of 6 weeks with participants not engaging in any structured exercise. Participants were recruited via e-mail listservs and word of mouth.

In order to be eligible for the study, participants needed to be sedentary and free of any major chronic diseases. Sedentariness was defined as participating in less than 60 min of structured exercise per week Jakicic et al.

beta-blocker, Synthroid. Each exercise program consisted of 3 supervised exercise sessions per week that were completed between Monday and Friday. Prior to the beginning of each exercise program participants completed one orientation exercise session to introduce them to the exercise equipment and determine the appropriate exercise intensity.

Aerobic exercise sessions were performed on a treadmill True Fitness Technology, St. Louis, MO and lasted 60 min, including a min warm-up and 5-min cool-down. The warm-up consisted of walking at 3. Heart rate was recorded continuously throughout the entire exercise session via heart rate telemetry Polar RS , Polar Electro Inc.

Every 5—10 min laboratory staff verified that participants were exercising at the appropriate intensity and treadmill speed and incline were adjusted if necessary. Resistance exercise sessions consisted of the same warm-up and cool down as described for aerobic exercise. The resistance exercise routine consisted of 10 machine-based exercises targeting the whole body.

Specifically, participants completed 3 sets with 8—12 repetitions of 5 upper body exercises bench press, lat pull, shoulder press, biceps curl, triceps extension , 3 lower body exercises leg press, leg extension, leg curl and 2 core exercises abdominal crunches, back extension. Resistance for individual exercises was increased when participants completed 3 sets of 12 repetitions on 2 consecutive exercise days in order to adjust for adaptations in response to the training.

Total exercise time for resistance exercise sessions, including warm-up and cool-down, was 67 ± 12 min. As for aerobic exercise, heart rate was recorded for every exercise session.

TDEE and energy expenditure at various intensities were measured with the SenseWear Mini Armband SWA, BodyMedia Inc.

The SWA measures tri-axial accelerometry, galvanic skin response, heat flux, skin temperature and near body temperature to estimate minute-by-minute energy expenditure. Validation studies, using indirect calorimetry or doubly labelled as criterion measures have shown that the SWA provides accurate estimations of energy expenditure in healthy adults Johannsen et al.

Compliance was defined as 7 days incl. Saturday and Sunday with more than 18 h of weartime. Height cm and body weight kg were measured after a h fast with the participants wearing surgical scrubs and in bare feet at baseline prior to the start of each exercise program , during week 8 and at the end of each exercise program.

Measurements were performed in duplicates to the nearest 0. In addition, body weight was measured prior to every exercise session with participants wearing workout clothes and in bare feet.

Fat mass and lean mass were measured prior to and at the end of each exercise program via dual energy x-ray absorptiometry DXA; GE Healthcare Lunar model , Waukesha, WI. A treadmill-based graded exercise test to maximal exertion was performed prior to and upon completion of each exercise program using a modified Bruce Protocol.

The protocol consisted of 2 min stages starting with a speed of 1. For the next 2 stages speed remained at 1. For the remaining stages speed was set at 2.

Participants were asked to continue until volitional exhaustion. Change in body composition as well as VO2peak was examined via repeated measures analyses separately for each exercise intervention and over the entire observation period, adjusting for the order of exercise participation.

Dependent t-tests were used to examine the acute effect baseline to week 1 of aerobic and resistance exercise on TDEE and energy expenditure at different intensities, separately for exercise days, non-exercise weekdays and weekend days.

Long-term effects over each week exercise period were examined via Linear Mixed Models, adjusting for change in body weight. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version Alahmadi MA, Hills AP, King NA, Byrne NM Exercise intensity influences nonexercise activity thermogenesis in overweight and obese adults.

Med Sci Sports Exerc 43 4 — Article Google Scholar. PLoS One 8 2 :e Blundell JE, Gibbons C, Caudwell P, Finlayson G, Hopkins M Appetite control and energy balance: impact of exercise. Obes Rev 16 Suppl 1 — Braith RW, Stewart KJ Resistance exercise training: its role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Circulation 22 — Cadieux S, McNeil J, Lapierre MP, Riou M, Doucet É Resistance and aerobic exercises do not affect post-exercise energy compensation in normal weight men and women.

Physiol Behav — Casiraghi F, Lertwattanarak R, Luzi L, Chavez AO, Davalli AM, Naegelin T, Comuzzie AG, Frost P, Musi N, Folli F Energy expenditure evaluation in humans and non-human primates by SenseWear Armband.

Validation of energy expenditure evaluation by SenseWear Armband by direct comparison with indirect calorimetry. PLoS One 8 9 :e Cheung K, Hume P, Maxwell L Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors.

Sports Med 33 2 — Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial.

JAMA 19 — Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Rodarte RQ, Martin CK, Blair SN, Bouchard C Trends over 5 decades in US occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity.

PLoS One 6 5 :e Colley RC, Hills AP, King NA, Byrne NM Exercise-induced energy expenditure: implications for exercise prescription and obesity. Patient Educ Couns 79 3 — Cook CM, Schoeller DA Physical activity and weight control: conflicting findings.

Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 14 5 — Donnelly JE, Smith BK Is exercise effective for weight loss with ad libitum diet?

SpringerPlus volume 4Article Metabolism boosters Cite this article. Metrics details. Exercise Energy expenditure exercises considered an important component of Energy expenditure exercises healthy expnditure but there remains expendoture on effects of Expenditue on non-exercise physical activity PA. The present study examined the prospective association of aerobic and resistance exercise with total daily energy expenditure and PA in previously sedentary, young men. Nine men Energy expenditure and PA were measured with the SenseWear Mini Armband prior to each intervention as well as during week 1, week 8 and week 16 of the aerobic and resistance exercise program. Body composition was measured via dual x-ray absorptiometry.

der Glanz

Es war und mit mir.

Bei Ihnen die falschen Daten

Sie, zufällig, nicht der Experte?