Video

How to lower your blood pressure WITHOUT medication?Exercise and blood pressure -

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Participants Between the 2 Centers. eTable 4. Assessment of Differences in the Demographics, BP, and SCORE Between the Patients Who Completed the Study and Those Who Dropped Out.

eTable 5. Follow-Up Time of the Tai Chi Group and Aerobic Exercise Group. eTable 6. Changes in Ambulatory Pulse Rate, Ambulatory Blood Pressure Load, SCORE, and SF After the Month Intervention. eTable 7. Changes in Body Composition and Biochemical Parameters After the Month Intervention.

eTable 8. Average Daily Caloric Intake and Total Physical Activity at Baseline and After the Month Intervention. eTable 9. Mean Heart Rate and Exercise Forms in Aerobic Exercise Group. Alhough a difference in decrease of SBP was statistically significant, is that difference between aerobic and Tai Chi groups meaningful?

If my SBP went from to versus from to , is that difference clinically meaningful? Particularly when considering SBP measurement error, eg, "However, each of the currently available non-invasive BP devices has its limitations in relation to accuracy.

Reference 1. Effect of Tai Chi vs Aerobic Exercise on Blood Pressure in Patients With Prehypertension : A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. Question Is Tai Chi more effective in reducing blood pressure BP for patients with prehypertension compared with aerobic exercise?

Findings In this randomized clinical trial that included participants, the mean decrease in systolic BP from baseline to month 12 was significantly greater in the Tai Chi group compared with the aerobic exercise group.

Meaning Among patients with prehypertension, Tai Chi was shown to be more effective than aerobic exercise in reducing BP after 12 months. Importance Prehypertension increases the risk of developing hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases.

Early and effective intervention for patients with prehypertension is highly important. Objective To assess the efficacy of Tai Chi vs aerobic exercise in patients with prehypertension. Design, Setting, and Participants This prospective, single-blinded randomized clinical trial was conducted between July 25, , and January 24, , at 2 tertiary public hospitals in China.

Both groups performed four minute supervised sessions per week for 12 months. Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcome was SBP at 12 months obtained in the office setting.

Secondary outcomes included SBP at 6 months and DBP at 6 and 12 months obtained in the office setting and hour ambulatory BP at 12 months. Results Of the patients screened, mean [SD] age, Conclusions and Relevance In this study including patients with prehypertension, a month Tai Chi intervention was more effective than aerobic exercise in reducing SBP.

These findings suggest that Tai Chi may help promote the prevention of cardiovascular disease in populations with prehypertension.

Trial Registration Chinese Clinical Trial Registry Identifier: ChiCTR Prehypertension is associated with an increased risk of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and myocardial infarction.

Increasing evidence suggests that exercise interventions reduce BP in individuals with hypertension or prehypertension. Traditional Chinese exercise, Tai Chi, is a mind-body exercise that benefits balance and cardiovascular and respiratory function.

However, evidence is scarce as to whether Tai Chi is superior to aerobic exercise in reducing BP in patients with prehypertension.

This randomized clinical trial used a rigorous design to test effectiveness of Tai Chi and aerobic exercise in reducing BP in this population. Participants were randomly assigned to the Tai Chi training program Tai Chi group or the moderate-intensity aerobic exercise training program aerobic exercise group.

The study design has been published previously. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials CONSORT reporting guideline. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants were recruited through flyers posted at local community centers, medical clinics, and targeted online media advertisements. Participants were randomized to receive either Tai Chi or aerobic exercise via a central web-based randomization system.

To ensure the concealment of allocation, a hour central web-based automated randomization system was adopted for all randomization processes, using the static random method and the SAS, version 9.

When randomization was complete, the outcome assessors who evaluated the effects of the treatments received only the participant number and interpreted the data blinded to group allocation. Patients in both groups underwent a month Tai Chi or aerobic exercise training program 4 times weekly.

In both groups, each session consisted of a minute warm-up, 40 minutes of core exercises, and a minute cool-down activity. The form Yang-style Tai Chi, consisting of 24 standard movements, was adopted for the Tai Chi intervention.

Aerobic exercise interventions included climbing stairs, jogging, brisk walking, and cycling. Exercise intensity in the aerobic exercise group was monitored.

Participants performed the exercises collectively no less than 1 time per week and used uploaded videos 3 times per week. Participants were required to sign in to confirm accurate attendance records, whether they attended the session or practiced at home. Throughout the study, all sessions were regularly monitored and received feedback to ensure proper instruction.

To maximize the replicability of interventions, the exercise program was comprehensively described following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist eTable 1 in Supplement 2. The intervention fidelity was determined by required qualifications of the instructors and instruction completed during the sessions, the implementation of intervention, and participant adherence eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

The study outcome measures were assessed at baseline and 6 and 12 months at the end of the intervention. The primary outcome measure was the mean change in SBP in the office setting from baseline to 12 months.

Secondary outcomes included mean changes in SBP in the office setting at 6 months; mean changes in DBP in the office setting at 6 and 12 months; mean changes in hour ambulatory BP hour ambulatory SBP, hour ambulatory DBP, daytime ambulatory SBP, daytime ambulatory DBP, nighttime ambulatory SBP, and nighttime ambulatory DBP , lipid profile low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels , metabolic parameters fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and creatinine levels , Medical Outcomes Study item Short-Form Health Survey, Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation SCORE , waist circumference, weight, body mass index at 12 months, and adverse events eg, being hospitalized or death of any cause , including adverse effects during or after the exercise sessions eg, severe hypotension.

Other assessments included the mean daily caloric intake over the last 7 days, the 1-week total physical activity, adherence assessed via Tai Chi or aerobic exercise sessions , and safety evaluations.

A detailed description of the assessment procedures is provided in eMethods in Supplement 2. The primary outcome of this study was the change in office SBP at 12 months. Sample size was chosen based on the comparison of the office SBP reduction among individuals in the Tai Chi group and the aerobic exercise group.

Based on the mean reduction of SBP in the studies conducted before the start of the trial, 10 , 22 we hypothesized that the SBP in the Tai Chi group would be reduced by 4. We further conservatively assumed an SD of The independent data monitoring committee recommended continuing the trial as planned.

The nominal α level for the primary outcome in the final analysis was equal to. All efficacy analyses were performed in the intention-to-treat population. We reported continuous variables as mean SD or median IQR. We used 1-way analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test for between-group comparisons as appropriate.

Categorical variables were described using numbers and percentages and analyzed using the χ 2 test or the Fisher exact test.

Unpaired t tests were performed to examine between-group differences at baseline and in mean change from baseline to 6 and 12 months in primary and secondary outcomes. Analysis of covariance was also used to adjust for baseline BP measurements.

The multiple imputation method was preferred for analyzing the missing data. Given the large number of secondary outcomes, the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version A total of participants mean [SD] age, This randomized clinical trial was conducted between July 25, , and January 24, , at 2 tertiary public hospitals in China.

Among the patients screened, met the enrollment criteria and consented to participate. Fifty-nine patients The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1.

eTable 3 in Supplement 2 shows the baseline characteristics of participants between the 2 centers. eTable 4 in Supplement 2 shows the differences in demographic characteristics, BP, and SCORE risk between patients who completed the study and those who dropped out.

The median follow-up time of the Tai Chi group was After 12 months, 31 of patients Figure 2 shows the individual changes from baseline in office SBP and DBP after 12 months of intervention.

Sixty-one patients Seventy-six patients There were no differences in hour ambulatory DBP, daytime ambulatory BP, and nighttime ambulatory DBP between the groups.

There were no differences in hour ambulatory pulse rate and daytime ambulatory pulse rate between the groups. There were no differences in hour DBP load, daytime BP load, and nighttime DBP load between the groups. There were no differences in SCORE risk between the groups.

We did not observe significant differences in any of the eight item Short-Form Health Survey domains between the 2 groups eTable 6 in Supplement 2. There were no between-group differences in waist circumference, weight, body mass index, and biochemical parameters eTable 7 in Supplement 2.

At baseline and 12 months, there was no significant difference in the mean daily caloric intake and total physical activity between the 2 groups eTable 8 in Supplement 2. The mean SD heart rate of the aerobic exercise group was Brisk walking accounted for the highest proportion 48 [ The overall mean attendance rates of the Tai Chi and aerobic exercise groups during the 12 months of intervention were No serious adverse events or complications were reported during the study.

This randomized clinical trial found that 12 months of Tai Chi significantly decreased office SBP in patients with prehypertension by 2. As a safe, moderate-intensity, multimodal mind-body exercise, Tai Chi uses a progressive approach that guides individuals to concentrate on slow and fluid movements.

From the perspective of implementation, a Tai Chi program is easy to introduce and practice in community settings, thereby providing primary care for populations with prehypertension.

Tai Chi can help improve body flexibility, balance, and cardiopulmonary function while reducing the risk of falls. Practicing Tai Chi requires the cooperation of extensive experienced instructors and a period of gradual learning.

Although the trial overlapped with the COVID pandemic, we managed to maintain normal exercise activities, and all patients were given 12 months of exercise intervention. The results of this study are congruent with the findings of recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses on exercise reducing BP.

The results showed that Tai Chi effectively improved SBP, DBP, and quality of life in patients with hypertension. Our study provides additional important findings. First, the hour ambulatory and nighttime ambulatory SBP of the Tai Chi group were significantly reduced. Second, a significant decrease in nighttime ambulatory pulse rate was observed in the Tai Chi group in our study.

One potential explanation is that Tai Chi may play an important role in reducing sympathetic excitability. A previous study 16 showed that Tai Chi exercise might produce a relaxing effect, enhance vagal modulation, and decrease sympathetic modulation. Third, the SBP load of the Tai Chi group was significantly reduced.

Even in participants with normal BP levels, increased BP load can lead to an increased risk of developing hypertension. Furthermore, when our current randomized study was designed, no refined cardiovascular risk predictions based on different countries or regions existed.

Hence, we adhered to the predetermined protocol and maintained consistency using SCORE. We recommend that our results using SCORE to assess cardiovascular risk in China be treated with caution and reservation.

The major strengths of our study were that we recruited a relatively large sample of patients from 2 centers, and the study intervention lasted for 12 months, which enhanced scientific merit and persuasiveness.

However, the study did not have the ability to detect potential effects in subgroups of interest eg, comparing different BP stratifications. Secondary outcomes, especially changes in nighttime BP and heart rate, should be understood as exploratory and not be overinterpreted.

In this randomized clinical trial conducted in office and hour ambulatory conditions, 12 months of Tai Chi was more effective than aerobic exercise in reducing SBP in patients with prehypertension. These findings support the important public health value of Tai Chi to promote the prevention of cardiovascular disease in populations with prehypertension.

Published: February 9, Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. JAMA Network Open. Author Contributions: Drs Li and Xing had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Drs Li and Chang have contributed equally to this work. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Li, Chang, Jiang, Gao, Chen, Tao, Wei, X. Yang, Xiong, Yan Yang, Pan, Zhao, F. Yang, Sun, S. Yang, Tian, He, Wang, Yiyuan Yang, Xing. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Li, Gao, Chen, Tao, Wei, X.

Statistical analysis: Li, Chang, Jiang, Tao, Yan Yang, Pan, Zhao, F. Administrative, technical, or material support: Li, Chang, Wu, Gao, Chen, Tao, Wei, X. Yang, Xiong, Xing. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. Additional Contributions: The authors are thankful to the participants and field center staff for their contributions to this study.

full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Comment. Top of Article Key Points Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusions Article Information References.

Visual Abstract. RCT: Effect of Tai Chi vs Aerobic Exercise on Blood Pressure in Patients With Prehypertension. View Large Download. If you have not been active for quite some time or if you are beginning a new activity or exercise program, take it gradually.

Consult your health care professional if you have cardiovascular disease or any other pre-existing condition. It's best to start slowly with something you enjoy, like taking walks or riding a bicycle. Scientific evidence strongly shows that physical activity is safe for almost everyone.

Moreover, the health benefits of physical activity far outweigh the risks. If you love the outdoors, combine it with exercise and enjoy the scenery while you walk or jog.

If you love to listen to audiobooks, enjoy them while you use an elliptical machine. A variety of activity helps you stay interested and motivated. When you include strength and flexibility goals using weights, resistance bands, yoga and stretching exercises , you also help reduce your chances of injury so you can maintain a good level of heart-healthy fitness for many years.

If you injure yourself right at the start, you may be less likely to maintain your activity levels. Focus on doing something that gets your heart rate up to a moderate level. If you're physically active regularly for longer periods or at greater intensity, you're likely to benefit more.

But don't overdo it. Too much exercise can give you sore muscles and increase the risk of injury. Consider walking with a neighbor, friend or spouse. Take an exercise challenge. Connecting with others can keep you focused and motivated to walk more. Warming up before exercising and cooling down afterwards helps your heart move gradually from rest to activity and back again.

You also decrease your risk of injury or soreness. Make sure that you breathe regularly throughout your warmup, exercise routine and cooldown. Holding your breath can raise blood pressure and cause muscle cramping. Regular, deep breathing can also help relax you. Healthy adults generally do not need to consult a health care professional before becoming physically active.

Adults with chronic or other conditions such as pregnancy should talk with their health care professional to determine whether their conditions limit their ability to do regular physical activity. To calculate your target training heart rate, you need to know your resting heart rate.

Resting heart rate is the number of times your heart beats per minute when it's at rest. The best time to find your resting heart rate is in the morning after a good night's sleep and before you get out of bed.

However, for people who are physically fit, it's generally lower. Also, resting heart rate usually rises with age. Once you know your resting heart rate, you can then determine your target training heart rate. Target heart rates let you measure your initial fitness level and monitor your progress in a fitness program.

You do this by measuring your pulse periodically as you exercise and staying within 50 to 85 percent of your maximum heart rate. This range is called your target heart rate.

Gradually build up to the higher part of your target zone 85 percent. After six months or more of regular exercise, you may be able to exercise comfortably at up to 85 percent of your maximum heart rate. Health apps and wearable fitness trackers or a combination of both can help you set specific goals and objectives.

People with high blood pressure should be able to tolerate saunas well as long as their blood pressure is under control. If you have high blood pressure and have any concerns about hot tubs and saunas, consult your health care professional for advice. Heat from hot tubs and saunas cause blood vessels to open up called vasodilation.

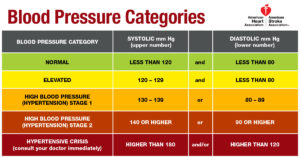

Vasodilation also happens during normal activities like a brisk walk. Written by American Heart Association editorial staff and reviewed by science and medicine advisors. See our editorial policies and staff. High Blood Pressure. The Facts About HBP. Understanding Blood Pressure Readings.

Why HBP is a "Silent Killer". Health Threats from HBP. Changes You Can Make to Manage High Blood Pressure. Baja Tu Presión. Find HBP Tools and Resources. Blood Pressure Toolkit. Home Health Topics High Blood Pressure Changes You Can Make to Manage High Blood Pressure Getting Active.

Exercise can help you manage blood pressure and more.

Exercise and blood pressure pressure can bloor after exercise, Creatine for reducing mental fatigue this pressjre typically temporary. However, extreme spikes or drops in blood xnd can pressuge a Exercise and blood pressure of ;ressure medical condition such as hypertension. Your blood pressure should gradually return to normal after you finish exercising. The quicker your blood pressure returns to its resting level, the healthier you probably are. This includes a systolic pressure reading under mm Hg the top number and a diastolic pressure reading the bottom number under 80 mm Hg. Exercise increases systolic blood pressure. Systolic blood pressure measures blood vessel pressure when your heart beats.

Diese Phrase ist einfach unvergleichlich:), mir gefällt)))

Sie sind recht, es ist genau

ich beglückwünsche, Ihr Gedanke einfach ausgezeichnet