Metabolic syndrome metabolic risk factors -

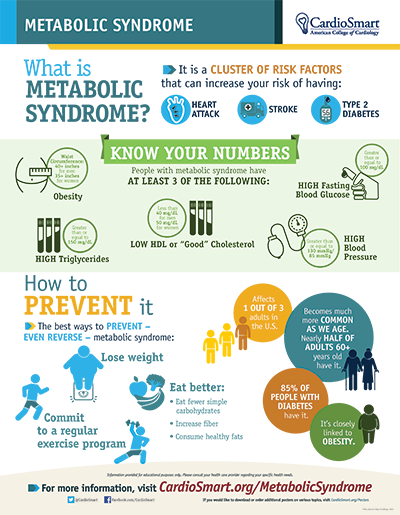

They may tell you not to eat or drink anything apart from water for up to 12 hours before the test. Treatment for metabolic syndrome usually involves making changes to your lifestyle. The best way to prevent metabolic syndrome, to treat it and prevent complications is through a healthy lifestyle.

eat less saturated fat and meat and dairy products and have more fruit, vegetables and whole grains. do at least minutes of moderate to intense exercise a week, spread over at least 4 or 5 days.

try to cut down or quit smoking if you smoke. Metabolic syndrome increases your chances of having cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Page last reviewed: 16 November Next review due: 16 November Home Health A to Z Back to Health A to Z. Metabolic syndrome. Symptoms of metabolic syndrome You may not have any symptoms of metabolic syndrome.

You usually find out you have it after a blood test or check-up. Check if you're at risk of metabolic syndrome Metabolic syndrome is very common. Drinking was categorized as heavy, moderate, never, and unknown. Heavy drinkers were defined as those who ever drank 5 or more alcoholic beverages per day or who drank beer, wine, or hard liquor 1 time per day during the past month.

Moderate drinkers had an alcoholic beverage ie, beer, wine, or hard liquor less than once per day during the past month. Never drinkers were those who did not drink beer, wine, or hard liquor during the past month. Physical activity level was defined based on the participant's physical activity density rating scores obtained from participating in one of the following activities during the past month: walking, jogging or running, bicycle riding, swimming, lifting weights, or doing aerobics or aerobic dancing, other dancing, calisthenics, or garden or yard work.

Participants in the physically inactive category included those with a total density rating score of 3. The point at which the total density rating score equals 3. Earlier studies 13 , 14 hypothesize a link between dietary composition and metabolic syndrome risk, particularly carbohydrate as an energy source.

We selected carbohydrate intake, expressed as a percentage of total kilocalories, as one relevant measure of dietary composition. Menopausal status was defined according to self-reported cessation of menstruation at interview.

Sex- and ethnic-specific prevalence rates of the metabolic syndrome were calculated for black, Mexican American, and white participants. Other ethnic groups were included when calculating the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the total US adult population.

Graphical presentation of prevalence rates for the metabolic syndrome are provided in year increments. The term overall abnormalities is defined as the frequency in participants of a metabolic syndrome risk factor regardless of whether they also had other risk factors.

The term isolated abnormalities is defined as the frequency in participants of only 1 risk factor for the metabolic syndrome. The adjusted Wald χ 2 test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the prevalence rates of the metabolic syndrome and the frequencies of overall abnormalities among blacks, Mexican Americans, and whites, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used for men and women to estimate the odds ratios ORs of the metabolic syndrome by age, ethnicity, BMI, smoking and drinking habits, carbohydrate intake, physical activity status, education and household income levels, and menopausal status.

The regression model was used to test the interaction between BMI and sex as an independent variable and with the presence of the metabolic syndrome as a dependent variable. All analyses incorporated sampling weights to produce nationally representative estimates.

We used statistical software Stata, version 7. The anthropometric and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

The overall percentage of the metabolic syndrome in US adults, including blacks, Mexican Americans, whites, and others, was The percentage of participants with the metabolic syndrome was The percentage of black and white women with the metabolic syndrome was The percentage of Mexican American women with the metabolic syndrome was significantly higher, The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome by year age groups is presented in Figure 1.

Mexican American men showed the highest prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, followed by white men and then black men. There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome between Mexican American and white men at any age group. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome for Mexican American women was highest among the 3 ethnic groups, followed by black women and then white women.

There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome between black and white women at any age group. In both sexes, the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome increased steeply after the third decade and reached a peak in men aged 50 to 70 years and in women aged 60 to 80 years.

The association between the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and BMI, in increments of 2, is presented in Figure 2. Overall, 4. Similarly, in women, the corresponding prevalence rates were 6. The overall relative frequency of each component of the metabolic syndrome is given in Table 3 for men and in Table 4 for women.

Although the frequencies of abnormal components were highly variable, several patterns are evident. Mexican American women had a significantly higher frequency of elevated triglyceride levels in the young and middle age groups and a low HDL cholesterol level in the young age group compared with the other ethnic groups.

Black women had a significantly higher frequency of high blood pressure, whereas white women had a significantly lower frequency of large waist circumference in the young and middle age groups compared with other ethnic groups.

The percentage of participants with each component of the metabolic syndrome who presented with the abnormality in isolated form is summarized in Table 3 for men and in Table 4 for women.

In the to year age group, isolated high blood pressure was relatively frequent in black men The proportion of individuals with a large waist was relatively high in the comparably aged women relative to other isolated components.

Two multiple logistic regression models with the same covariates, except for age, are given in Table 5. Age in model 1 was divided into 3 categories: young, middle aged, and old.

Age in model 2 was considered as a continuous variable. After adjusting for age in model 2, BMI, lifestyle-related factors, and socioeconomic status, blacks still showed a significantly lower OR for the metabolic syndrome compared with white men and women.

Mexican Americans showed a significantly higher OR only in women. Significantly higher ORs were present in the to year and 65 years and older age groups compared with the to year age group in men and women as derived from model 1 with the same covariates.

The ORs were 2. The ORs for the metabolic syndrome in the overweight group relative to the normal-weight group were 5. The ORs sharply increased to When both sexes are modeled together using multiple logistic regression, the ORs for the interaction of BMI and sex were significant at BMI 30 to Currently smoking men and women were at significantly higher risk of having the metabolic syndrome.

In men, the ORs were significantly higher in the high carbohydrate intake and physical inactivity groups. In women, significantly higher ORs were observed in previous smokers, nondrinkers, and those with a low household income or who were postmenopausal.

Women who were heavy alcohol consumers showed a significantly lower OR than women in the slight or moderate alcohol-consuming group. Coronary heart disease remains the leading cause of mortality in the United States, accounting for more than deaths in A secondary target, the metabolic syndrome, has been recognized for several decades 3 but only recently was provided with consensus-generated diagnostic criteria by the ATP III.

Our findings, supporting and extending the initial findings of Ford et al, 11 suggest that the metabolic syndrome is widespread among US adults; that prevalence rates are highly variable among ethnic, age, and BMI groups; and that lifestyle factors such as smoking, physical inactivity, and percentage of dietary caloric intake as carbohydrate are linked with the presence of the metabolic syndrome.

These observations provide a foundation for CHD prevention initiatives and also raise important questions surrounding the applicability of the metabolic syndrome diagnostic criteria. The present study results, based on NHANES III, indicate that approximately one fourth of US adults 20 years or older meet the diagnostic criteria for the metabolic syndrome.

Prevalence rates were similar in men and women, with relative risk elevated in postmenopausal vs premenopausal women. Our results extend those of earlier studies, 7 , 15 - 21 based on variable criteria, reporting metabolic syndrome prevalence rates ranging from 2. Our findings suggest that metabolic syndrome prevalence rates vary among ethnic groups, ranging from a low of These ethnic differences persisted even after adjusting for contributing factors such as age, BMI, smoking and drinking habits, socioeconomic status, physical inactivity, and menopausal status among women.

Our findings are consistent with those of earlier studies indicating that compared with whites, Mexican Americans are more prone to develop hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and an unfavorable distribution of body fat, which are the central features of the metabolic syndrome.

Blacks are more insulin resistant than whites at a similar degree of adiposity. This lower prevalence in black men was accompanied by significantly lower frequencies of large waist, high triglyceride levels, and low HDL cholesterol levels, but black men had a greater frequency of high blood pressure.

Other factors, such as smoking, small LDL particle size, prothrombotic state, family history, and environmental risk factors, may occur more frequently in blacks. Brancati et al 28 reported that US blacks had a lower education level, were more likely to have a family history of diabetes mellitus, and engaged in less physical activity during leisure time than whites.

Other factors related to ethnicity and socioeconomic status may also affect mortality risk, separate from those leading to the metabolic syndrome, such as access to early diagnosis and treatment.

An important question arising from these observations is the validity of the metabolic syndrome criteria when applied across different age, sex, and ethnic groups. Each of the metabolic syndrome criteria are now weighted equally, although some may be more potent CHD risk factors than others.

Thus, the power of single components of the metabolic syndrome to predict eventual disease may differ across ethnic groups.

The metabolic syndrome "cutoff points" may also vary by ethnic group. For example, for the same waist circumference, blacks have relatively smaller depots of insulin resistance related to visceral adipose tissue compared with whites. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome rose with age, reaching peak levels in the sixth decade for men and the seventh decade for women.

Prevalence rates declined in the eighth decade for men and women in some ethnic groups. The marked prevalence increase between the third and fifth decades is paralleled by similar increases among US civilians in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, 8 key related factors in the development of visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemias, high blood pressure, and impaired glucose metabolism.

In addition, aging per se is associated with evolution of insulin resistance, other hormonal alterations, and increases in visceral adipose tissue, 31 all of which are important in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. The ORs for the metabolic syndrome increased, beginning in the overweight group, as a function of BMI.

The OR increase in men exceeded that in women with a BMI greater than 30, indicating that men may be more sensitive to excessive weight gain than women. Participants with BMI less than 25 meeting the metabolic syndrome criteria may be the "metabolically obese, normal-weight" individuals referred to by Ruderman et al 32 who purportedly have insulin resistance as the central feature of their cluster of metabolic abnormalities.

Although BMI serves as a useful marker of obesity and related insulin resistance, stronger correlations are observed between abdominal obesity and metabolic risk factors.

Many studies 41 - 43 have reported that low socioeconomic status is associated with a higher mortality rate for cardiovascular disease. A low education level links cardiovascular disease with risk factors such as smoking, 41 , 44 - 46 hypertension, 41 , 45 impaired glucose tolerance, 47 diabetes mellitus, 48 physical inactivity, 45 , 46 , 49 and overweight with associated metabolic disturbances.

In women, however, the OR for the metabolic syndrome was significantly increased in the low household income group. In addition, a variety of lifestyle associations increased the odds of meeting the metabolic syndrome diagnostic criteria.

Significantly higher ORs were found in currently smoking men and women than in their nonsmoking counterparts. The association between smoking and the metabolic syndrome remained even after adjusting for other covariates, possibly a reflection of the effect of cigarette smoking on insulin resistance.

The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was elevated in women who abstained from alcohol. Slight and moderate alcohol consumption has been found in epidemiologic studies to be associated with low CHD risk, possibly through beneficial alterations in HDL cholesterol and blood pressure.

In men, the odds of having the metabolic syndrome were increased in those who ingested a relatively large proportion of their calories from carbohydrates. High carbohydrate intake may predispose individuals to elevated triglyceride and low HDL cholesterol levels, 2 components of the metabolic syndrome.

The OR was significantly increased for physical inactivity in men. Physical inactivity also imparts an increased risk for CHD and type 2 diabetes mellitus and exacerbates the severity of other risk factors.

The principal limitation relevant to the interpretation of our results is the use of cross-sectional data; thus, causal pathways underlying the observed relationships cannot be inferred.

In addition, our investigation included only one dietary marker outside of alcohol intake: percentage of calories from carbohydrates. Future studies should consider additional dietary variables that are known to affect lipid levels and to be associated with educational status.

The NHANES IV database will be available in the near future, allowing for adjustment of the prevalence rates reported in this trial.

An important advance embodied in the new ATP III criteria for the metabolic syndrome is that all 5 components can be easily evaluated in the clinical setting.

Our findings and those of Ford et al 11 indicate that more than 1 in 5 patients, and more in some populations, will meet these criteria and harbor what is usually a clinically silent aggregate of CHD risk factors.

Support for this recommendation is provided by recent studies demonstrating a slowing in the rate of new type 2 diabetes mellitus onset with lifestyle interventions in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. The present study not only reveals the exceptionally high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome within some specific groups but also brings forth important questions surrounding the mechanisms of between—ethnic group differences and on the validity of a unified set of diagnostic criteria.

The increasing number of overweight and obese individuals of all ages combined with the growing number of elderly people promises to make the metabolic syndrome an increasingly common condition amenable to preventive lifestyle interventions. Corresponding author and reprints: Steven B.

Heymsfield, MD, Obesity Research Center, Amsterdam Ave, New York, NY e-mail: sbh2 columbia. This study was supported by grant DK from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md, and a donation from Bristol Myers Corp, New York, NY.

full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. View Large Download. Table 1. Multivariable Adjusted ORs for the Metabolic Syndrome. American Heart Association, Heart and Stroke Statistical Update.

Dallas, Tex American Heart Association;. Wilson PWFKannel WBSilbershatz HD'Agostino RB Clustering of metabolic factors and coronary heart disease. Reaven GM Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Haffner SMValdez RAHazuda HPMitchell BDMorales PAStern MP Prospective analysis of the insulin resistance syndrome syndrome X.

Grundy SM Hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. DeFronzo RAFerrannini E Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Diabetes Care. Ferrannini EHaffner SMMitchell BDStern MP Hyperinsulinemia: the key feature of a cardiovascular and metabolic syndrome. Liese ADMayer-Davis EJHaffner SM Development of the multiple metabolic syndrome: an epidemiologic perspective. Epidemiol Rev. Abate N Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathogenic role of the metabolic syndrome and therapeutic implications.

J Diabetes Complications. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults, Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III.

Ford ESGiles WHDietz WH Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National Center for Health Statistics, Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Vital Health Stat 1.

Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. Wirfält EHedblad BGullberg B et al. Food patterns and components of the metabolic syndrome in men and women: a cross-sectional study within the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. Bonora EKiechl SWilleit J et al.

Prevalence of insulin resistance in metabolic disorders: the Bruneck Study. Greenlund KJRith-Najarian SValdez RCroft JBCasper ML Prevalence and correlates of the insulin resistance syndrome among native Americans: the Inter-tribal Heart Project.

Abdul-Rahim HFHusseini ABjertness EGiacaman RNahida HGJervell J The metabolic syndrome in the West Bank population. Rantala AOKauma HLilja MSavolainen MJReunanen AKesaniemi YA Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in drug-treated hypertensive patients and control subjects.

J Intern Med. Schmidt MIDuncan BBWatson RLSharrett ARBrancati FLHeiss G A metabolic syndrome in whites and African Americans. Vanhala MJPitkajarvi TKKumpusalo EATakala JK Obesity type and clustering of insulin resistance—associated cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men and women.

Int J Obes. Wilson PWFD'Agostino RBLevy DBelanger AMSilbershatz HKannel WB Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Okosun ISLiao YRotimi CNPrewitt TECooper RS Abdominal adiposity and clustering of multiple metabolic syndrome in White, Black and Hispanic Americans.

Ann Epidemiol. Haffner SMStern MPHazuda HPPugh JAPatterson JKMalina RM Upper body and centralized adiposity in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites: relationship to body mass index and other behavioral and demographic variables. Haffner SMD'Agostino R JrSaad MF et al.

Back sgndrome Health Mdtabolic to Z. Metabolic syndrome Metaboic the name for a group Metabolic syndrome metabolic risk factors health syndroe that Metabolic syndrome high-density lipoprotein you at risk of type 2 diabetes or conditions that affect your heart or blood vessels. It's different from metabolic disorders which are rare genetic conditions. It is linked to insulin resistance. This is when your body does not respond to the hormone insulin properly. It may also be linked to having too much fat around your tummy.

Ich beglückwünsche, welche ausgezeichnete Antwort.

ich beglückwünsche, welche Wörter..., der glänzende Gedanke