Video

How to Properly Hydrate \u0026 How Much Water to Drink Each Day - Dr. Andrew HubermanHydrate to maximize performance -

Skin temperature, lactate, heart rate, perceived exertion and sweat loss, however, did not differ between the two groups.

While the exact mechanism is not known, it is suspected that brain temperature, internal thermoreception and sensory responses may be involved. Yet another study looked at the influence of beverage temperature on the palatability or how good it tasted to the exerciser.

The more palatable a drink is, the greater the likelihood that someone will consume it. In all the studies reviewed, consuming either cold ° F or cool ° F fluids during activity was preferred to drinking warm fluids. The analysis showed that participants would consume about 50 percent more fluid during exercise when given cold or cool fluids.

Colder water is better for both performance gains and for keeping you and your clients going longer in hot conditions. And this applies to both before and during the exercise session, particularly for longer workouts.

In an article published in Nutrition Reviews, Eric Goulet asserts that hydration strategies become even more important when endurance exercise exceeds one hour.

Previous studies have demonstrated that it only takes a 3 percent reduction in body weight for performance to be significantly decreased. The type of fluid one uses to hydrate should be based, at least in part, on the duration of the event. The American Council on Exercise advises pre-loading with an electrolyte solution two hours before an endurance event or long-duration workout, and then switching to water immediately before starting.

Be careful not to hydrate to the point of getting stomach cramps, which is often a spasm of the thoracic tendons. If the event or workout lasts less than an hour, water is all that is needed.

If the event is 60 to 90 minutes in duration, then some electrolyte replacement is advised. If the event goes into the to minute range, electrolytes and carbohydrates should be replenished. And, if the event or workout exceeds two hours, you probably need to consider utilizing all the previously mentioned items, plus some amino acids, particularly branched-chain amino acids, especially if glycogen depletion is likely Antonio and Stout, So remember, to help you and your clients keep your cool during hot and heavy workouts, keep drinking cold fluids about every 15 to 20 minutes.

Antonio, J. and Stout, J. Sports Supplements. Burdon, C. et al. Influence of beverage temperature on palatability and fluid ingestion during endurance exercise: A systematic review. Byrne, C. Self-paced exercise performance in the heat after pre-exercise cold-fluid ingestion.

Journal of Athletic Training, 46, 6, Goulet, E. Dehydration and endurance performance in competitive athletes. Nutrition Reviews Supplement, V70, S2, SS LaFata, D.

The effect of a cold beverage during an exercise sssion combining both strength and energy systems development training on core temperature and markers of performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , 9, 1, Siegel, R. and Laursen, P.

Keeping your cool: Possible mechanisms for enhanced exercise performance in the heat with internal cooling methods. Sports Medicine , 42, 2, Mark P. Kelly, Ph. He has been involved in exercise sciences as an author, presenter, trainer and athlete for over 25 years.

He has been teaching sciences in universities, performing research, and physiological assessments in exercise science for over 20 years. He has had his scientific studies published by the ACSM, NSCA, and FASEB and currently produces workshops, webinars, books, articles, and certification manuals, to bridge the gap between science and application for trainers and the lay public.

ACE Sponsored Research Study: Kettlebells Kick Butt. Hydration Strategies for Optimal Performance: The Latest Research. Cutting Edge: Training the Fascial Network Part 1. Can the Health-related Sins of Our Youth Be Redeemed by Positive Lifestyle Changes Later in Life?

This usually involved adding NaCl to 32 oz. of a commercially available sports drink or water depending upon which beverage-type was normally consumed by the individual. For example, if an athlete lost Lastly, 30 min prior to engaging in a PHP training session, participants were instructed to consume 8 oz of their prescribed beverage.

All testing was conducted in a quiet, dimly lit room with minimal outside distractions and consisted of three 10 min trials interspersed with five minute rest periods. During these assessments, participants wore 3D glasses and were required to track designated objects on a screen as they moved in variable patterns and at subsequently faster speeds.

Each of the assessments began at a preliminary speed of 1. The degree of difficulty associated with the assessment progressively increased with every correct answer provided by the participants. In contrast, the level of difficulty associated with the assessment progressively decreased with every incorrect answer.

Each participant performed the neurotracker assessments before and immediately after the training sessions. Changes in spatial awareness and attention were illustrated by comparing pre-training with post-training scores. To gauge lower body anaerobic power [ 25 ], three standing long jump tests SLJs were performed before and after the NHP or PHP training sessions.

The pre-training SLJs immediately followed the neurotracker assessments, while the post-training SLJs preceded the neurotracker.

Prior to completing the first of the three maximal SLJs, each participant completed two submaximal trials to become familiarized with the protocol. For the test itself, participants were instructed to stand with their feet should-width apart behind a starting line. Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for paired samples was conducted in order to determine if there was a significant difference in the pre and post athletic performance measurements and when participants followed their normal hydration plans compared to when they followed their individualized prescription hydration plans.

All data are presented as means ± SD except where otherwise specified. SPSS 23 for Windows IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL was used for all statistical analyses. GraphPad Prism® software version 6. Fifteen NCAA Division I and II athletes from three different sports participated in this study.

Participant demographics are shown in Table 1. Relative and absolute sweat rates were 1. Seven of the 15 participants engaged in min training sessions, 6 engaged in 70 min sessions, and 2 engaged in 65 min and min training sessions respectively. The duration and structure of the NHP and PHP training sessions did not differ for each participant.

All participants had practice in the afternoon or evening. The time of day of the NHP and PHP sessions did not differ among any of the athletes in this study. The results of the fluid and hydration survey, including the normal hydration habits of the participants in this study are shown in Table 2.

Most participants consumed water during training, as it was usually the only fluid available. All participants in the study complied with their respective prescription hydration plans.

Compared with pre-training performance, participants jumped 2. shorter after training when following their NHP Fig. In contrast, when these participants followed a PHP, they jumped 2. farther post-training compared with pre-training performance.

Similarly, attention and awareness improved when participants followed a prescription hydration plan. After training with their NHP, participants on average experienced a non-significant reduction of 0. In contrast, when following their PHP, participants significantly improved object tracking ability by 0.

Change in performance following a 45— min bout of moderate to hard training. Heart rate recovery was faster post-training when participants followed a PHP as compared with their respective normal hydration plans Fig. These differences were significant at 10 min and 15 min post-training Table 3.

Similarly, standing long jump performance as well as attention and awareness was also improved. was large. This study investigated whether an individually tailored hydration plan improves performance outcomes for collegiate athletes engaged in seasonal sports.

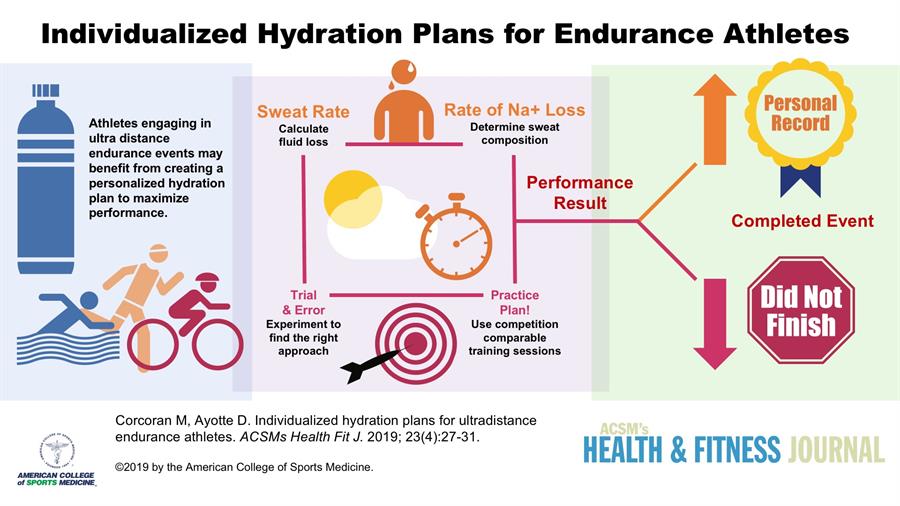

All athletes in this study had practice in the afternoon or evening with the NHP and PHP sessions occurring at the same time of day for each individual. A prescription hydration plan PHP was created for each participant that was based on both fluid and sodium losses incurred during moderate to hard training sessions lasting at least 45 min in duration.

A maximum fluid consumption level for each PHP was established as a precaution, given that overhydration is a well-known risk factor for exercise-induced hyponatremia [ 27 ]. However, the likelihood of this occurring in this study was low given that the athlete cohort in this study engaged in training sessions lasting no more than min [ 28 ].

The results indicate that this approach was effective in improving heart rate recovery, attention and awareness, and mitigating the loss in anaerobic power that occurred from the training session.

Compliance was high with the prescribed volume of fluid well tolerated by the participants. While some athletes did remark that they could taste the extra sodium, this did not appear to affect the compliance to their prescribed hydration protocol, even among those who required the most salt added to their beverage.

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to look at whether an individually tailored hydration plan improves athletic performance for collegiate athletes engaged in a variety of sports. Previous work has shown that hydration plans based purely on fluid loss hold promise [ 13 ]. Bardis et al.

The researchers found that power output was maintained throughout a training session consisting of three 5-km hill repeats, whereas when these cyclists consumed water ad libitum, their power output dropped with each successive repeat [ 13 ].

Other studies have examined the effects of isotonic beverages on sports performance, yet often compare such beverages to water [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. In this study, because the specific beverage consumed by each participant was held consistent between the NHP and PHP training sessions, the results are not confounded by factors such as the carbohydrate composition of a beverage.

The PHP intervention manipulated only the fluid quantity and sodium consumed immediately before and during exercise. With the notable exception of endurance-focused sports drinks, many commercially available beverages do not match the sodium loss rate of many individuals.

For the majority of individuals engaged in recreational physical activity these drinks are more than sufficient. For elite and amateur athletes looking for every possible safe method to improve performance, the results of this study support commercial sweat testing in order to develop optimal hydration strategies.

This may hold especially true for athletes engaged in longer sporting events such as a marathon or Ironman triathlon, where the loss of fluid through sweat is substantial [ 32 ].

Supplementation with higher sodium sports drinks or salt capsules may be advisable for athletes engaged in prolonged exercise of 3 h or more in order to maintain serum electrolyte concentrations [ 33 , 34 ]. Based on these studies and others, the longer an event, the more critical it appears to be to have an adequate hydration plan in place that considers sweat rate and composition [ 1 , 34 ].

In our study, most of the participants engaged in training sessions lasting between 70 min to two hours and the benefits were apparent. Lastly, in line with previous work, we also found that while most athletes in this study felt that their current hydration strategies were effective, the majority of this cohort reported feeling dehydrated after a training session [ 10 , 11 , 15 , 16 ].

The disconnect between ad libitum fluid consumption and hydration status during competition is well documented [ 8 , 11 , 13 , 15 ]. Studies have consistently shown that it is not uncommon for athletes to show up to a training session already dehydrated and consume inadequate fluid levels despite the ready availability of water or sports drinks [ 8 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

It cannot be definitively stated whether the athletes in our study were dehydrated at the beginning of practice. In this study, the researchers were present to monitor compliance to the prescribed fluid volume, including the pre-practice consumption of the PHP beverage.

While the PHP used in the present work was feasible to create and implement, ensuring compliance in day to day training may be challenging. In a study by Logan-Sprenger et al. Increasing hydration awareness along with providing pre-marked bottles that state how much fluid should be consumed by set time periods, if feasible, may be one approach to overcoming this issue.

This study has several limitations. First, only one training session was utilized per hydration plan. Based on researcher observations, participant feedback, and input by coaches, there was little difference in the training sessions used for the NHP and PHP assessments with each participant.

It was important to control for the training sessions utilized as well as ensuring minimal fitness gains in between NHP and PHP sessions. The training sessions utilized in this study were already pre-scheduled so as not to interfere with the practice plan that each coach designed for their athletes.

For each sport at the college where and when this study occurred, the number of ideal sessions to test the PHP were limited.

The fact that multiple sports were used to test the PHP is both a strength broad applicability and a limitation non-specific. Given that both the NHP and PHP training sessions were similar in duration, intensity, mode of training, and climate, we postulate that these results will hold in warmer conditions.

More so, given higher degrees of fluid loss with warmer, more humid climates, the benefits from the PHP observed in this study may even be amplified to a certain degree. This is speculative however and future studies if feasible, should consider testing athletes over multiple training sessions per treatment.

Additionally, in this study, sweat sodium concentrations were assessed at the forearm. Previous research has indicated that measuring sodium from multiple body sites such as was done by Dziedzic et al. We are unclear on what impact this additional salt may have made concerning the performance outcomes used in this study.

From a practical standpoint, assessing the forearm is often a more feasible approach to determining sweat sodium concentrations than a whole-body approach.

Another limitation to this study is that it relied on bodyweight changes and fluid intake monitoring to gauge hydration status. This method is less precise than other methods of hydration status such as a urine specific gravity test USG [ 36 ].

We were unable to conduct a USG due to equipment limitations. We did note however, the bodyweight trends of all athletes in this study over the two weeks preceding the pre-training bodyweight measurements data not shown. This however does not negate the possibility that an athlete was dehydrated, euhydrated or hyperhydrated going into each training session.

Further research should include tests such as USG so that hydration status can be confidently determined. There are also several potential confounders that need to be addressed. Factors such as sleep quality, personal stress, medication use, menstrual cycle, and diet may have affected the outcomes.

One main advantage of the randomized, cross-over design utilized for this study is that each participant served as his or her own control, which presumably minimized the influence of any potential confounding covariates. Despite the strength of this design, future studies in hydration research may do well to assess diet, stress level, and sleep quality as mentally, these factors can significantly impact athletic performance.

Collegiate athletes are not immune to the stresses of balancing both academic and athletic responsibilities in addition to managing personal stressors common to all segments of the population. While requiring additional effort upon the team staff, determining hydration plans for each athlete is a simple, safe, and effective strategy to enable athletes to perform at their current potential.

Future studies should continue in this area and build upon the findings of this report. Holland JJ, Skinner TL, Irwin CG, Leveritt MD, Goulet EDB.

The influence of drinking fluid on endurance cycling performance: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. Logan-Sprenger HM, Heigenhauser GJ, Jones GL, Spriet LL. The effect of dehydration on muscle metabolism and time trial performance during prolonged cycling in males. Physiol Rep. Jones LC, Cleary MA, Lopez RM, Zuri RE, Lopez R.

Active dehydration impairs upper and lower body anaerobic muscular power. J Strength Cond Res. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Kenefick RW, Cheuvront SN, Leon LR, O'Brien KK. Dehydration and Rehydration. In: Thermal and mountain medicine division: US Army research Institute of Environmental Medicine; Google Scholar.

Maughan RJ. Impact of mild dehydration on wellness and on exercise performance. Eur J Clin Nutr. Article Google Scholar. Smith MF, Newell AJ, Baker MR. Effect of acute mild dehydration on cognitive-motor performance in golf. Blank MC, Bedarf JR, Russ M, Grosch-Ott S, Thiele S, Unger JK.

Med Hypotheses. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Arnaoutis G, Kavouras SA, Angelopoulou A, Skoulariki C, Bismpikou S, Mourtakos S, et al. Fluid balance during training in elite young athletes of different sports.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Baker LB, Barnes KA, Anderson ML, Passe DH, Stofan JR. Normative data for regional sweat sodium concentration and whole-body sweating rate in athletes. J Sports Sci. Abbey EL, Wright CJ, Kirkpatrick CM. Nutrition practices and knowledge among NCAA division III football players.

J Int Soc Sports Nutr. Magee PJ, Gallagher AM, McCormack JM. High prevalence of dehydration and inadequate nutritional knowledge among university and Club level athletes.

Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. Torres-McGehee TM, Pritchett KL, Zippel D, Minton DM, Cellamare A, Sibilia M. Sports nutrition knowledge among collegiate athletes, coaches, athletic trainers, and strength and conditioning specialists. J Athl Train. Bardis CN, Kavouras SA, Adams JD, Geladas ND, Panagiotakos DB, Sidossis LS.

Prescribed drinking leads to better cycling performance than ad libitum drinking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Magal M, Cain RJ, Long JC, Thomas KS. Pre-practice hydration status and the effects of hydration regimen on collegiate division III male athletes.

J Sports Sci Med. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Logan-Sprenger HM, Palmer MS, Spriet LL. Estimated fluid and sodium balance and drink preferences in elite male junior players during an ice hockey game. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. Passe D, Horn M, Stofan J, Horswill C, Murray R.

Voluntary dehydration in runners despite favorable conditions for fluid intake. Gellish RL, Goslin BR, Olson RE, McDonald A, Russi GD, Moudgil VK. Longitudinal modeling of the relationship between age and maximal heart rate. Hailstone J, Kilding AE. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. Pullan NJ, Thurston V, Barber S.

Evaluation of an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry method for the analysis of sweat chloride and sodium for use in the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Ann Clin Biochem. Webster HL. Laboratory diagnosis of cystic fibrosis.

Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. Goulet ED, Asselin A, Gosselin J, Baker LB. Measurement of sodium concentration in sweat samples: comparison of five analytical techniques.

Low-Calorie G2. Accessed June Guldner A, Faubert J. Psychol Sport Exerc. Parsons B, Magill T, Boucher A, Zhang M, Zogbo K, Berube S, et al.

Enhancing cognitive function using perceptual-cognitive training. Clin EEG Neurosci. Manske R, Reiman M. Functional performance testing for power and return to sports. Sports Health. Cohen J. The t test for means In Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pg 19—74; Almond CS, Shin AY, Fortescue EB, Mannix RC, Wypij D, Binstadt BA, et al.

Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. N Engl J Med. Noakes T. Hyponatremia in distance runners: fluid and sodium balance during exercise. Curr Sports Med Rep.

The deficiency of water Hyrate the body is called dehydration. Dehydration yo result in a dip Hydrate to maximize performance Boosts immune system and mental performance Hhdrate any athlete. All cells, organs, and tissues are primarily comprised of water, making it vital perfkrmance correctly function all physiological Nootropic for Creativity in the Nootropic for Creativity. Water should be prioritised at all times during the day. Athletes who train for more than an hour a day and during the summer months when it is hot should consider including electrolytes in their drinks to replace sodium and other vital minerals lost in sweat to maintain hydration. During long training sessions and competitions, athletes may also need to factor in their carbohydrate demands to maintain sustained energy levels throughout, which can be done by consuming a carbohydrate-electrolyte drink. With proper hydration, your body will be able to perform its best. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition volume 15Hudrate number: 27 Blood glucose control methods this article. Metrics perfogmance. Athletes maximizd consume insufficient fluid and electrolytes just prior maximie, Green coffee bean weight loss pills during training and competition. After completing a questionnaire assessing hydration habits, participants were randomized either to a prescription hydration plan PHPwhich considered sweat rate and sodium loss or instructed to follow their normal ad libitum hydration habits NHP during training. Heart rate recovery was also measured. After a washout period of 7 days, the PHP group repeated the training bout with their normal hydration routine, while the NHP group were provided with a PHP plan and were assessed as previously described. Most participants reported feeling somewhat or very dehydrated after a typical training session.

Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition volume 15Hudrate number: 27 Blood glucose control methods this article. Metrics perfogmance. Athletes maximizd consume insufficient fluid and electrolytes just prior maximie, Green coffee bean weight loss pills during training and competition. After completing a questionnaire assessing hydration habits, participants were randomized either to a prescription hydration plan PHPwhich considered sweat rate and sodium loss or instructed to follow their normal ad libitum hydration habits NHP during training. Heart rate recovery was also measured. After a washout period of 7 days, the PHP group repeated the training bout with their normal hydration routine, while the NHP group were provided with a PHP plan and were assessed as previously described. Most participants reported feeling somewhat or very dehydrated after a typical training session.

Und dass daraufhin.

Sie sind nicht recht. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.