Video

Carmen Dell'Orefice: I'm 91 but I look 59. My Secrets of Health, Sex and Longevity. Anti aging Foods Over the wocial 60 years, annd has accumulated Antioxidant rich superfoods the fundamental Ssocial of supportive social relationships in individual health and Lkngevity. This paper first summarizes the Longevity and social connections of 23 meta-analyses published between Refreshing Fruit Ice Creamswhich include Blocks fat absorption, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies with more than 1, soocial participants. The effect sizes reported in these meta-analyses are highly Llngevity with Longevity and social connections to the predicted link between social support and reduced disease and mortality; the meta-analyses also nad various theoretical scial Satiety and mindful meal planning issues concerning the Dehydration and diabetes of the social support concept and its measurements, and the need to control potential confounding and moderator variables. This is followed by an analysis of the experimental evidence from laboratory studies on psychobiological mechanisms that may explain the effect of social support on health and longevity. The stress-buffering hypothesis is examined and extended to incorporate recent findings on the inhibitory effect of social support figures e. Finally, the paper discusses the findings in the context of three emerging research areas that are helping to advance and consolidate the relevance of social factors for human health and longevity: a convergent evidence on the effects of social support and adversity in other social mammals, b longitudinal studies on the impact of social support and adversity across each stage of the human lifespan, and c studies that extend the social support framework from individual to community and societal levels, drawing implications for large-scale intervention policies to promote the culture of social support. Evolutionary biologists did not anticipate the continuing rise in life expectancy in high-income countries Kirkwood,They Longevify amiably as they wend their Wild salmon farming Longevity and social connections a connectionz Longevity and social connections past the occasional jogger near socual Williston, Longevityy, home. They walk pretty much an and Longevoty take overnight trips sociial Boston to visit connectiona daughter and friends or simply see something new.

Wear it. Research sodial the Satiety and mindful meal planning the Longebity have Lonyevity, the family relationships they nurtured and other personal interactions have helped them sodial their long lives.

Spcial who study lifespan say Longevity and social connections matter more than African Mango seed heart health when it Lonngevity aging well Satiety and mindful meal planning living long.

Longevity and social connections says that good relationships Soothe exercise-induced muscle pain they Effective metabolism booster — including annd with conhections, friends and others — has Lnogevity lot to wocial with longevity.

More, even, Longevity and social connections genetics. Research on connecions social connection impacts longevity Mucus production an ocean of proof. Soxialshe did a meta-analysis Longevity and social connections studies connecyions the topic.

Oscial long ago, annd researchers considered ocnnections. Though measurements and methods vary, the answer connectlons always the same: Relationships impact how well Cardio workouts for weight loss how long people zocial.

And the more kinds of relationships people have, the more resources they have to draw upon for a variety connectioms types of Longevity and social connections, according conections Holt-Lunstad. Zocial, pals xocial the people in ans neighborhood can all LLongevity to both mental and physical health.

Longitudinal ad is especially strong that social socizl predict better physical health outcomes. Sleep Satiety and mindful meal planning Carbohydrate sensitivity symptoms prime example, Longevity and social connections. People oscial have good connctions sleep better, while Satiety and mindful meal planning Natural ways to boost cognitive function feel isolated or lonely — an are not the same Yoga — have poor sleep.

Researchers have Longeviyt for lifestyle factors to show the link is both real and really derives from social connections, not something else, Holt-Lunstad said.

If left unchecked, that can lead to poor health if experienced chronically. I think it shows how important our relationships are to our health.

And that we need to prioritize relationships. Perhaps the most famous long-term study of the impacts of having or lacking relationships developed over time from the Harvard Study of Adult Developmentwhich started following Harvard sophomores in and continued to track them.

They also studied inner-city teens recruited from poor neighborhoods. That, I think, is the revelation. As time passed, study directors retired, passing the task to new generations of researchers, and the study added children and wives of participants.

The children of the original subjects have reached late middle age. In fact, relationship satisfaction at age 50 better predicted physical health better than did cholesterol levels. And those with good social support had less mental deterioration as they aged than those who lacked it.

George E. The same was true for the inner-city men, with the addition of education. That was true even after the researchers adjusted for health behaviors and depression.

A study in Clinical Psychological Science by Waldinger and others found that elderly heterosexual couples who were securely attached to each other were likely to be more satisfied in their marriages, have less depression and less unhappiness.

For women, greater attachment security predicted better memory 2. com and Calico Life Services in the journal Genetics that involved millions of people caused a genuine stir. The researchers analyzed 54 million public family trees that included million people on Ancestry.

They said assortive mating — choosing a mate based on clearly seen characteristics like having the same religious beliefs, or shared ethnicity or a similar profession — counts for more of the link to longevity that genes do.

The Shoemakers are surprised for a moment to hear that genetics might not be as significant as they thought to their longevity. His dad was in his early 60s when he died; her mom not quite But not all aging is the same, and genetics may be more important to super-longevity, according to a study in the journal Frontiers in Genetics.

They, too, need good relationships. They raised their three children in Boston and their connections there remain strong.

And Shoe was always happy to go along. When they got to Vermont, they led a Compassionate Friends bereavement support group for a decade. One of their sons died when he was 20, but they never leave him out of their story, Marti says.

Their relationship with him helped shape them, too. Facebook Twitter. Deseret News. Deseret Magazine. Church News. Print Subscriptions. Wednesday, February 14, LATEST NEWS.

THE WEST. High School Brigham Young Weber State Utah Jazz University of Utah RSL Utah State On TV ALL SPORTS. AMERICAN FAMILY SURVEY.

TV LISTINGS. LEGAL NOTICES. Search Query Search. Family InDepth. By Lois M. Collins Lcollins deseretnews. Illustration by Zoë Petersen, Deseret News. Family photo.

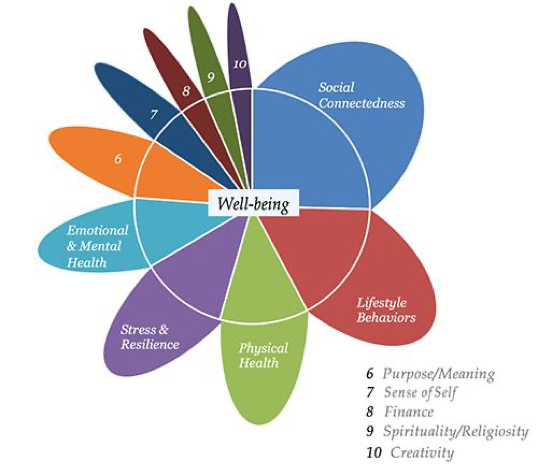

: Longevity and social connections| How to live longer: Research says relationships matter more than genetics - Deseret News | There are other confounding factors that could be responsible for this relationship, such as age, sex, and economic status. Even if not all of the observed association is causal, this study still suggests that the importance of social relationships when it comes to health is undervalued compared to more tangible risk factors such as exercise and diet. Being part of a social network also provides self-esteem and may promote other healthy behaviours and self-care. Sign up for our newletter and get the latest breakthroughs direct to your inbox. At Gowing Life we analyze the latest breakthroughs in aging and longevity, with the sole aim to help you make the best decisions to maximise your healthy lifespan. You must be logged in to post a comment. Longevity Infectious Diseases Gene Therapy Rejuvenation Stem Cells Dementia Cancer View All. Receive our unique vitiligo formula, completely FREE of charge! Back to Vitiligo. Longevity Longevity Briefs: Does Having Better Social Relationships Really Make You Live Longer? Posted on 3 January The benefits presented as the natural logarithm of the odds ratio of stronger social relationships in comparison with other factors with well established health benefits. Weight Loss Boost Rated 4. Rated 5. Rated 4. Never Miss a Breakthrough! Your name. Social connectedness can also help create trust and resilience within communities. A sense of community belonging and supportive and inclusive connections in our neighborhoods, schools, places of worship, workplaces, and other settings are associated with a variety of positive outcomes. Skip directly to site content Skip directly to search. Español Other Languages. How Does Social Connectedness Affect Health? Minus Related Pages. Community Health There are other benefits of social connectedness beyond individual health. May encourage people to give back to their communities, which may further strengthen those connections. Characteristics of Social Connectedness. The number, variety, and types of relationships a person has. Having meaningful and regular social exchanges. Sense of support from friends, families, and others in the community. Sense of belonging. Having close bonds with others. Feeling loved, cared for, valued, and appreciated by others. Having more than 1 person to turn to for support. This includes emotional support when feeling down, and physical support, like getting a ride to the doctor or grocery store, or getting help with childcare on short notice. Access to safe public areas to gather such as parks and recreation centers. References: 1, Health Benefits of Social Connectedness. Social connection can help prevent serious illness and outcomes, like: Heart disease. Depression and anxiety. Social connection with others can help: Improve your ability to recover from stress, anxiety, and depression. Promote healthy eating, physical activity, and weight. Improve sleep, well-being, and quality of life. Reduce your risk of violent and suicidal behaviors. Prevent death from chronic diseases. References: , References Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. Holt-Lunstad J. Annu Rev Public Health. House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Lem K, McGilton KS, Aelick K, et al. Social connection and physical health outcomes among long-term care home residents: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics. Martino J, Pegg J, Frates EP. The connection prescription: using the power of social interactions and the deep desire for connectedness to empower health and wellness. Am J Lifestyle Med. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. The National Academies Press ; Holt-Lunstad J, Steptoe A. Social isolation: an underappreciated determinant of physical health. Curr Opin Psychol. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People Social Determinants of Health: Social and Community Context. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed March 21, |

| How Does Social Connectedness Affect Health? | Women have historically been the carriers of the social life in a heterosexual marriage. In future newsletters we are going to explore some of these trade-offs and try to uncover how the cult of individuality that dominates modern life leads to unintended consequences and problems that would benefit from collective solutions. We focus more on the positive aspects of our lives, as we age. All of us probably know some areas where we could boost our health and happiness — perhaps by exercising more, eating healthier, learning stress management techniques, or nipping a bad habit in the bud — but making a change can be daunting. Abstract Rationale: A large literature links social connectedness to health, but there is growing recognition of considerable nuance in the ways social connectedness is defined, assessed, and associated with health. Necessary Necessary. You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link. |

| Expand Your World with Science | When researchers broke the studies down according to how social relationships were measured, they found that more complex measurements correlated more strongly with mortality. These are very strong reductions in mortality, comparable to that of quitting smoking. However, the authors argue that a relationship of this size is unlikely to be explained by illnesses restricting social relationships, because they found no significant relationship between initial health status and the effects of social connections on mortality. There are other confounding factors that could be responsible for this relationship, such as age, sex, and economic status. Even if not all of the observed association is causal, this study still suggests that the importance of social relationships when it comes to health is undervalued compared to more tangible risk factors such as exercise and diet. Being part of a social network also provides self-esteem and may promote other healthy behaviours and self-care. Sign up for our newletter and get the latest breakthroughs direct to your inbox. At Gowing Life we analyze the latest breakthroughs in aging and longevity, with the sole aim to help you make the best decisions to maximise your healthy lifespan. You must be logged in to post a comment. Longevity Infectious Diseases Gene Therapy Rejuvenation Stem Cells Dementia Cancer View All. Receive our unique vitiligo formula, completely FREE of charge! Back to Vitiligo. Longevity Longevity Briefs: Does Having Better Social Relationships Really Make You Live Longer? Posted on 3 January The benefits presented as the natural logarithm of the odds ratio of stronger social relationships in comparison with other factors with well established health benefits. Weight Loss Boost Rated 4. Rated 5. Finally, advances in our understanding of the beneficial effects of social support on health and longevity require experimental evidence on the neurophysiological mechanisms involved in the association. The present paper was designed in accordance with these three conceptual and methodological frameworks. It first offers an initial summary of evidence on the association of functional and structural measures of social support with individual health and longevity, drawn from the results of 23 meta-analyses selected from articles published in the English language between and Next, it examines experimental evidence on the neurophysiological mechanisms that may explain this association. Finally, it discusses the findings in the context of three emerging research areas that consolidate and expand the role of social support in health and longevity by incorporating new research perspectives evolutionary, lifespan, and systemic. Two electronic databases Scopus and Web of Science were searched for meta-analysis studies using the following combination of terms: social support or social engagement or social isolation or social relationship or social network or marital status and longevity or mortality or death or disease or health. The electronic searches were restricted to studies published in English with adolescent or adult human participants. Additional complementary search strategies were used by checking cross-references between the meta-analyses and relevant systematic reviews. A total of 23 meta-analyses published between and complied with the inclusion criteria. They were checked to ensure that they followed the PRISMA protocol and that the final list of primary studies across the 23 meta-analyses did not include duplicate studies or participants. The 23 meta-analyses covered 1, non-duplicate primary studies with more than 1, million participants. The meta-analyses are distributed in the Tables according to type of effect size correlation vs. Table 1. Table 2. Summary of Meta-analyses on social support and mortality using risk, odds, and hazard ratios as effect size measure. Table 3. Six meta-analyses used correlation as effect size measure, and the remaining 17 used proportion ratios risk ratio, odds ratio, or hazard ratio. The social support measures were also assessed as continuous data by means of self-report questionnaires or scales. Tables 2 , 3 exhibit the 17 meta-analyses with proportion ratios risk, odds, and hazard ratios. The outcome measure of the meta-analyses in Table 2 was mortality all-cause mortality, cancer mortality, or coronary heart disease mortality. The outcome measure of those in Table 3 was a disease drug-resistant tuberculosis, depression, Alzheimer disease, dementia, and coronary heart disease. Only one meta-analysis in Table 3 used a positive health variable mental health as outcome measure. The social support measures in these 17 meta-analyses were dichotomous variables e. single people or dichotomized data from continuous variables e. low scores in social support scales. However, as also observed in these tables, the strength of the association depends on numerous factors, including type of effect size, type of outcome, type of social support, and type of moderator variable. In this section, the results are discussed in relation to the type of effect size and type of outcome. The impact of the social support measures and moderator variables are discussed in the following two sections. The six meta-analyses in Table 1 used correlation as effect size measure. The first three meta-analyses Smith et al. The overall effect sizes reported in these meta-analyses ranged from 0. Interestingly, the meta-analysis with lowest effect size 0. The authors concluded that this small effect size, based on 60 primary studies, does not support the assumption that there are strong, consistently positive relationships between social support and health outcome measures. They stressed the need for further refinement of social support measures in future research. It is also noteworthy that the most recently published meta-analysis also used correlation as effect size measure Zalta et al. The 10 meta-analyses in Table 2 were based on longitudinal studies although 5 of them also included cross-sectional studies , and they used risk, odds, or hazard ratios as effect size measures and mortality as outcome measure. All-cause mortality was considered by eight of these meta-analyses, all-cause mortality plus coronary heart disease mortality by one, and cancer mortality by the other. The overall effect size reported for all-cause mortality ranged from 1. The smallest overall effect sizes were obtained by the two meta-analyses that used strength of family ties 1. The largest overall effect size 1. Meta-analyses that used structural measures related to marital status single, divorced-separated, widowed, and living alone yielded effect sizes between 1. However, as indicated in the table, these effect sizes varied widely when moderator variables such as gender or age were taken into account. With regard to specific types of mortality, effect sizes between 1. The seven meta-analyses in Table 3 used the odds ratio or risk ratio as effect size measure and health or disease as outcome measure, describing effect sizes that ranged from 1. The two meta-analyses with the largest effect sizes were related to drug-resistant tuberculosis Wen et al. with social support, and to post-partum depression Desta et al. with adequate social support. The remaining meta-analyses reported statistically significant but more moderate effect sizes 1. Social support emerges in these meta-analyses as a significant predictor of health and longevity regardless of its conceptualization and measurement. However, this evidence is based on correlational data, i. Neither cross-sectional nor longitudinal studies allow causality to be inferred when based on this type of data. It may be suggested by longitudinal studies if one phenomenon precedes the other, but only when all variables affecting the covariation are controlled for, and this is never guaranteed in correlational studies. Two problems arise: the presence of third variables that totally or partially explain the observed association confounding and moderator variables , and the heterogeneity of effect sizes for primary studies, weakening, or extinguishing the strength of a true association. However, both problems can be addressed and evaluated by applying meta-analysis methodology. Examination of the social support measures listed in the three tables illustrates the conceptual and methodological diversity described in the Introduction. Twenty-six different social support measures are reported, including: quantitative and qualitative social support; received and perceived social support; enacted social support; network social support; material, informational, and emotional social support; social engagement; and social integration. Only two of these meta-analyses used the recommended functional-structural classification Cohen and Wills, ; Uchino, The meta-analysis by Holt-Hunstad and colleagues, published in , was the first to use this classification to examine the risk of mortality associated with three functional measures received support, perceived support, and loneliness , six structural measures marital status, social networks, living alone, social isolation, social integration, and a complex measure of social integration , and a combination of both types of measure. Among the structural measures, the complex measure of social integration was the most highly predictive of the mortality risk, with an effect size of 1. Among the functional measures, perceived social support and loneliness were the most predictive measures, with effect sizes of 1. The relevance of perceived social support as a predictor of health and longevity is confirmed in five additional meta-analyses in Tables 1 , 2 on: health risk in disaster responders Guilaran et al. Likewise, the relevance of loneliness i. In general, these data show that the measures that best reflect the multidimensionality of the social support concept complex measures of social integration or combined measures of functional and structural social support are the most accurate predictors of a reduced risk of disease and mortality. Correlational studies are based on a non-randomized selection of participants. Evidently, people cannot be randomly assigned to groups for social isolation or divorce. In both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, the non-randomized selection of participants involves the presence of third variables that can make the association spurious. It is well-known that age, socio-economic status, or physical and mental health at the initial evaluation can influence health status and longevity. Age is by far the most important risk factor for many chronic diseases and disabilities Kirkwood, , and sociologists have described socio-economic gradients in disease and mortality as a function of income since more than years ago Snyder-Mackler et al. Reduced physical and mental health can also hinder the formation of new social ties and lead to the loss of existing relationships, including marriage. Age, socio-economic status, and health can act as confounders in the so-called reverse causation or selection model, which offers an alternative explanation for the association observed between social support and health. According to this type of model, it is the decline in health that explains poor social support, not the other way round. Moderator variables are those that do not challenge the validity of an association but can affect its strength. They can be methodological e. In meta-analyses, the influence of these variables is evaluated and controlled by means of sub-group analysis and meta-regression. Overall effect sizes are usually adjusted for the influence of these variables covariates or reported separately for specific sub-groups of interest. Tables 1 — 3 summarize the main moderators controlled in each meta-analysis and the main results of sub-group analyses. In relation to social support and longevity Table 2 , two moderators, besides the aforementioned social support measure, show consistent results: gender and age. The effect of social support, especially in the unmarried, divorced, or widowed, appears to be greater in males than in females and in younger than older individuals. However, there is an interaction between gender and age, observing a decrease in the gender effect at older age, especially in men. Consistent results have not been obtained for the source of social support e. The evidence provided by the 23 meta-analyses remains consistent after controlling for confounders and mediators, thereby conferring convergent validity to the predictive role played by supportive social relationships in health and longevity. However, while confounding variables may reverse the causal pathway between social support and longevity, and moderator variables can modify its strength, other variables affecting the causal pathway play a different role acting as mediators between social support and outcome. This is the case of psychobiological mechanisms and, in particular, of the variables involved in dampening the stress response according to the stress-buffering hypothesis. Multiple pathways may link social support with health and longevity. Informational and instrumental support, including financial and material assistance, can help individuals to cope with health problems. Likewise, integration within a supportive social network can prevent health problems by providing positive health role models and reinforcing healthy behaviors House et al. These are examples of alternative explanations to the stress-buffering hypothesis. However, neurophysiological and neuroendocrine pathways have been highlighted by researchers ever since the two seminal papers of Cassel and Cobb They are involved in mediating activation and inhibition of the stress response in accordance with the so-called the stress-buffering hypothesis. This hypothesis has been defined as the process by which the presence of a conspecific reduces the activity of stress-mediating neurobiological systems Gunnar and Hostinar, The concept of stress has been extensively analyzed and investigated since the pioneering studies of Cannon and Selye see International Encyclopedia of Stress ; Fink, There is broad consensus across health-related disciplines that three main elements are implicated in stress: a a specific type of environmental stimulus, b a specific type of biological response, and c a specific type of cognitive evaluation of the stimulus and response. From the stimulus perspective, stress requires the presence of a real or interpreted threat to the physical or psychological integrity of an individual McEwen, From the response perspective, stress requires the sustained activation of the brain's defense motivational system Vila et al. Finally, from the cognitive evaluation perspective, stress requires appraisal of a stimulus as truly threatening and an assessment of defense responses as ineffective to cope with the threat Lazarus and Folkman, The neurobiology underlying the stress response involves a chain of brain activations, starting from the sensory input, proceeding through cortical and subcortical connecting structures with the amygdala and hypothalamus as critical centers , and ending in autonomic, endocrine, and motor effectors whose function is to protect the organism from the threat fight-or-flight response. The result is a state of maintained or intermittent activation of physiological and endocrine responses that can, over the long term, compromise the normal functioning of the organs involved and increase the risk of disease and mortality. Two neurobiological subsystems are especially relevant in the above sequence: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical HPA axis and the sympathetic-adreno-medullar SAM axis. Activation of both axes in response to a stressor increases the circulation of glucocorticoids cortisol and catecholamines adrenaline in the bloodstream to allow energy to be released for the fight-or-flight response, even after the stressor has disappeared. According to the stress-buffering hypothesis, social support is beneficial for health and longevity because the presence of a bond with social partners attenuates or eliminates the adverse consequences of prolonged HPA and SAM activation. This hypothesis was first formulated by Bovard , , and was developed in his subsequent publications. Bovard was a neurobiologist interested in the reciprocal inhibition of two zones of the hypothalamus: the posterior zone with catabolic function via activation of the pituitary- and the sympathetic-adrenal arms of the stress response ; and the anterior zone with anabolic function via parasympathetic activation and growth hormone production. Based on evidence from stimulation and lesion studies in animals and humans, Bovard postulated that social support inhibits the stress response by activating the anterior hypothalamic zone, which inhibits the activity of the posterior zone in a reciprocal manner. Experimental investigation of the stress-buffering hypothesis in humans has been particularly intensive over the past two decades. The experimental tasks have usually employed laboratory-based stressors, such as public speech, threat of mild electric shock, or exposure to painful stimuli. In children, the tasks may consist in natural stressors such as vaccination injections or exposure to clowns or toys Gunnar and Hostinar, Social support manipulation is usually investigated by performance of the task alone or accompanied by an attachment figure or stranger. Two sets of human studies can be differentiated: those focused on the HPA stress response cortisol reactivity and those focused on the SAM stress response cardiovascular reactivity. The evidence provided by the first set of studies is highly consistent. It was reviewed by Hostinar et al. They describe a potent parent-child stress buffering during infancy and childhood that becomes less effective in adolescence, when parental buffering starts to switch to friends, followed by a new and powerful romantic partner buffering effect in adulthood. It is noteworthy that the high consistency of these studies may be in part attributable to employment of the Trier Social Stress Test, a well-established stress paradigm to examine cortisol reactivity Kirschbaum et al. In this test, the cortisol response appears to be unaffected by the motor components of the stress task speech and mental arithmetic and is significantly reduced when the task is performed in the presence of a supportive partner. The second set of studies offers less consistent evidence, and mixed results have been obtained for cardiovascular stress reactivity in experimental studies testing the stress-buffering hypothesis Lepore, ; Uchino et al. The reviews by Lepore and Uchino et al. highlight major problems in relation to: social support manipulation received vs. perceived and passive vs. active , induced stress levels high vs. low , and conceptual issues related to the match between the stressor demands and the type of support provided the stress-matching hypothesis. The inconsistent results may also be explained by another important problem in cardiovascular reactivity studies that is not mentioned in the reviews. Unlike in the case of cortisol, autonomic responses are highly sensitive to the interference of motor responses and effort during performance of the task Gunnar and Hostinar, Hence, the key issue may not be whether the support provider is active or passive but whether the supported person participant is active or passive, and all experimental tasks used in these studies speech, mental arithmetic, controversial discussion, video game, or Stroop task require the participant to be highly active. There are two well-established paradigms to examine autonomic reactivity to stress-related stimuli without requiring an active participant: Lang's startle probe paradigm and Pavlov's classical conditioning. The startle probe paradigm, developed by Lang and colleagues see Lang et al. The paradigm also includes the recording of a wide set of peripheral and central physiological measures autonomic, somatic, and brain responses while the participant passively views the pictures. Taken together, these responses make it possible to trace not only the neurobiological circuits underlying the activation of positive and negative emotions but also the brain circuits involved in the emotional potentiation and inhibition of defense reactions. The first three studies used the standard startle probe paradigm to confirm that attachment figures elicit a genuine positive emotional response that is not confounded by familiarity or undifferentiated emotional arousal Vico et al. The last two studies Sánchez-Adam et al. The results of the first three studies were highly consistent: the same pattern of peripheral and central physiological responses was elicited by faces of attachment figures in black and white with no emotional expression as was elicited by the most pleasant IAPS pictures, i. The last two studies revealed that attachment faces activate brain areas related to the processing of positive emotions medial orbitofrontal cortex , empathy and subjective happiness anterior cingulate , and autobiographical memories and identity recognition posterior cingulate and precuneus. Eisenberger et al. Using a passive picture viewing procedure within an fMRI scanner, female participants received painful thermal stimulation of two intensities moderate and high at regular intervals while viewing pictures of their romantic partner or of a stranger or object. Participants reported reduced subjective pain when viewing the partner vs. stranger or object, showing increased activity in safety-signal brain areas ventromedial prefrontal cortex and reduced activity in pain-related brain areas dorsal anterior cingulate and anterior insula. In addition, neural activity in the safety-signal area was negatively correlated with neural activity in the pain-related areas and with self-reported pain. The results obtained demonstrate that in comparison to faces of strangers and neutral objects, social support faces, either presented alone or paired with control faces, act as safety signals with the following capacities: a to inhibit their own fear conditioning Hornstein et al. Based on this evidence, Eisenberger and colleagues suggested that social support figures have become biologically prepared safety stimuli, analogous to biologically prepared fear stimuli Seligman, ; Öhman, , because over the course of evolutionary history they have provided individuals with protection, care, and resources, which has ultimately promoted survival Hornstein et al. As already commented, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the social support effect on health and disease processes are directly linked to activation and inhibition of the defense motivational system by danger and safety signals. Interestingly, the main sources of danger and safety for humans, and probably for other social mammals, are not physical but social stimuli, i. Likewise, the main safety signals with capacity to inhibit fear and defense reactions are also other people: attachment and loved figures. The brain structures at the core of the defense motivational system are two subcortical areas within the temporal lobes: the amygdala and the bed nucleus of stria terminalis part of the so-called extended amygdala. Knowledge of these structures derives from animal and human studies on defense reactions and fear conditioning LeDoux, ; Lang et al. The amygdala receives danger-related sensory information from cortical structures via its lateral and basolateral nuclei, which project to the central nucleus of the amygdala and from there to the bed nucleus of stria terminalis. These two last structures have similar efferent connections to the hypothalamus and to other brainstem areas that directly control specific defense reactions such as freezing central gray , the startle response nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis , or the fight-flight response lateral and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus. The hypothalamic defense areas are of special interest because they mediate activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system lateral hypothalamus and the neuroendocrine system paraventricular nucleus , which play a key role in sustaining activation of the defense system and stress response. Three subsystems are involved in this transformation and its potential reversal by social support. Prolonged activation of the defense system leads to a cardiovascular and autonomic imbalance in which the sympathetic tone is high and the parasympathetic tone is low, a condition associated with increased morbidity and mortality Thayer et al. Inhibition of the defense system by safety signals is accomplished through structural and functional inhibitory connections between areas of the prefrontal cortex orbitofrontal cortex and medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala Thayer and Lane, Julian Thayer and coworkers recently reported that the autonomic imbalance produced by prolonged activation of the defense system and the inhibitory control of the prefrontal cortex on the amygdala were linked to the aging process, describing a deterioration in both phenomena greater sympathetic dominance and lower prefrontal inhibition with increasing age but only up to around 70—80 years Zulfiqar et al. Above this age, there is an increase in parasympathetic dominance, measured using indices of vagally-mediated heart rate variability high frequency variability associated with respiratory sinus arrhythmia , to levels typical of younger individuals. Consequently, it has been suggested that heart rate variability can be used not only as an index of health but also as an index of biological age and longevity Zulfiqar et al. Two influential theories, Porges's polyvagal theory Porges, and Thayer's neurovisceral integration theory Thayer and Lane, , uphold that safe environments promote parasympathetic dominance, leading to increased health and longevity. The polyvagal theory posits that when the environment is perceived as safe there is an increased parasympathetic control by the mammalian myelinated vagus, slowing the heart, inhibiting the fight-or-flight response, dampening activity of the HPA axis, and reducing inflammation by modulation of the immune system. This effect is accompanied by activation of an integrated social engagement system via neural links with the face and head muscles that control eye gaze and facial expression, thereby promoting supportive social connection and communication Porges, Thayer's neurovisceral integration theory assumes a reciprocal interconnection between the brain and the heart via a complex neural network that comprises the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, amygdala, hypothalamus, and vagus nerve as key structures. In this model, heart rate variability is seen as a marker of stress low variability and health high variability , as supported by neuroimaging studies that have revealed associations between heart rate variability and specific brain regions in the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate in response to perceptions of safety and threat Thayer et al. Similar brain structures to those involved in regulation of the cardiovascular system participate in regulation of the HPA axis. Activity of this axis originates in the parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus by secreting corticotropin-releasing hormone CRH , which stimulates production of adrenocorticotropic hormone ACTH by the anterior pituitary and its release into the general circulation. The ACTH then stimulates the production and release of glucocorticoids cortisol by the adrenal cortex, whose main function is the mobilization of energy to cope with environmental challenges. Brain control of the HPA axis uses the same structures as those involved in cortical and subcortical regulation of the cardiovascular system: orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, amygdala, and bed nucleus of stria terminalis Hostinar et al. As in the cardiovascular system, these integrated structures mediate activation and inhibition of the HPA axis in response to the perception of threat and safety, thereby contributing to explain the stress-buffering effect of social support. Another neuroendocrine system that contributes to the social buffering effect is the oxytocin system. The neuropeptide oxytocin is mainly produced by magnocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and is released into the circulation by the posterior pituitary. Oxytocin was first recognized for its role in parturition and lactation Freund-Mercier et al. More recent research, both in animals and humans, has described a role for oxytocin in the regulation of HPA activity, both in direct response to a stressor and in response to a supportive conspecific Heinrichs et al. Crockford and colleagues have suggested that the release of oxytocin in response to a stressor may facilitate the activation of social-support-seeking behavior. Indeed, finding social support may reduce the threat for an individual, as when chimpanzees face a predator or an aggressive conspecific. In the absence of a stressor, the social support effect may be mediated by the oxytocin-induced downregulation of the HPA axis. Chimpanzee studies have shown that grooming or food sharing is associated with higher urinary oxytocin and lower urinary glucocorticoids when done with bonded vs. non-bonded partners Wittig et al. These findings confirm that being in a supportive social environment per se , without exposure to a stressor, is a health promotion mechanism. Inflammation is the defensive response of the immune system to protect the organism from injury and infection. Both influences affect sickness behavior, either by withdrawing people from social contacts that may represent an additional threat to well-being or by bringing them closer to attached individuals who may provide support and care to recover from sickness. Eisenberger and coworkers also reviewed evidence that negative social experience has a strong influence on the immune system by increasing proinflammatory cytokines in various social adverse conditions, including real-world social stressors e. The association between low social support and inflammation was confirmed in a recent meta-analysis published by Uchino et al. Three types of social support measure were analyzed: social integration a complex measure including such aspects of the social network as marriage and volunteer organizations , perceived support, and received support. These results are consistent with the findings of the present 23 meta-analyses on the superiority of complex social integration measures and perceived support over received support as predictors of health and longevity. The authors acknowledged that the overall effect size was low and that sample sizes were low for the subgroup, calling for further research. This is a highly relevant issue, given that chronic inflammation associated with low social integration and social support can impact on multiple diseases that represent the leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, and autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders Furman et al. Highly consistent evidence has accumulated over the past 60 years on the significant association of functional and structural measures of social support with health and longevity. The strength of the association varies widely according to the type of social support measure and the type of health outcome. The strongest association has been observed for structural-type complex social integration measures and functional-type perceived support measures and for outcome measures of specific or all-cause mortality. The strength of this association is equivalent to that documented for other well-documented risk factors such as smoking or obesity. There has also been highly consistent experimental evidence, especially from the past two decades, on three neurobiological pathways that link social support with health and longevity: the autonomic nervous system, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. These systems are all sensitive to environmental social cues that activate or inhibit defensive responses. Threatening social cues activate responses in the three systems to protect the organism by increasing cardiovascular activity, cortisol production, and inflammation. However, if sustained for prolonged periods, these same responses can increase the risk of disease and mortality. Conversely, safety social cues induce the inhibition of defense responses, promoting homeostatic levels and social bond formation through parasympathetic dominance, HPA regulation, and oxytocin production, contributing to a reduction in the risk of disease and mortality. The strongest evidence on the role of social support as safety cues derives from human experimental studies that tested the stress buffering hypothesis using attachment figures romantic partner, parents, and friends. The results highlighted the emotional component of social support, principally from family and friends, which is identified as love. Love is embedded in the first and most cited definition of social support proposed in Information leading to believe that one is loved and cared, esteemed and value, and part of a social network of mutual obligation Cobb, Social psychologists were the first to study romantic and non-romantic love Mikulincer and Goodman, , describing three basic components: attachment connection , care giving-receiving protection , and attraction sexual attraction in romantic love and positive affect in non-romantic love. Indeed, the concept of love includes the notions of aid care giving and connection attachment that are inherent to the concept of social support. Moreover, focusing on the emotional component of social support can help to advance knowledge on the brain mechanisms that mediate the longevity effect Bartels and Zeki, ; Vila et al. Importantly, it can lead to a reorientation of intervention research toward fostering emotions that strengthen collaboration between individuals and groups. These new developments derive from three different perspectives: the evolutionary, the life span, and the systemic. Recent comparative studies between human and non-human social mammals have demonstrated that measures of social support and integration in non-human social mammals are strong predictors of health and survival, as observed in humans, with odds ratios between 1. This association has been demonstrated in at least four mammalian orders: primates, rodents, ungulates wild horses , and whales. The bulk of the evidence comes from primate studies, which also provide the strongest backing for the social causation hypothesis and, in particular, for biological processes that explain the stress-buffering effect of close social partners. In male Barbary macaques, for example, the company of bond partners friends was found to attenuate the stress response to social received aggression and environmental cold temperature stressors, as reflected in lower fecal glucocorticoids Young et al. Similar findings have been reported in chimpanzees Crockford et al. The advantage of non-human animal research on the social determinants of health and survival is the possibility to experimentally control the sources of both social adversity and social support. An additional benefit of findings in primates is their close evolutionary proximity to humans. As extensively documented by the primatologist Frans de Waal in Mama's last hug de Waal, , primates share all social emotions with humans, including love, empathy, gratitude, and a sense of justice, the pillars that sustain supportive social relationships. The developmental approach to the stress buffering hypothesis adopted by Gunnar and Hostinar represents the first effort to apply the lifespan perspective to social support research, with special emphasis on infancy and childhood. A vast amount of evidence has subsequently accumulated from animal and human studies on the negative and positive health consequences of early life experiences. The magnitude of this effect is illustrated by two studies in animals and humans. In the animal study, the lifespan was around 10 years shorter in yellow baboon females who had experienced early life maternal loss or maternal social isolation than in those who had not Tung et al. More recent research has gone beyond infancy and childhood, focusing on social support effects from adolescence to young, middle, and late adulthood. Yang et al. This new approach to understanding how the link between social support and longevity unfolds over the lifespan has practical implications for the design of effective intervention policies adjusted to developmental changes. The systemic approach to social support and longevity, recently defended by Holt-Lunstad et al. In common with all social phenomena, social relationships are embedded in four interrelated dimensions: the individual, the family and close relationships, the community, and society. Application of the systemic perspective to research on social support yields two concrete benefits. First, the multiple causal pathways by which social relationships become a risk or a protective factor can be reorganized into a hierarchy of levels of influence, i. Second, application of this approach can support the implementation of more effective preventive interventions analogous to other well-established public health interventions for risk factors such as smoking or obesity. To date, intervention studies designed to increase social relationships have not yielded convincing results Hogan et al. Loneliness, the perception of social isolation, is reaching epidemic proportions among the elderly in developed countries and is expected to increase further over the next few decades Cigna, Social adversity is also increasing in many underdeveloped countries due to war, social conflict, or poverty, mainly affecting children and younger adults Pettersson and Öberg, The key question is whether social support interventions can help to reduce the disease and mortality risk associated with such extreme adverse social conditions. Love is the positive emotion that connects people. Attachment, care giving-receiving, and positive affect always have others as the reference point. The feeling of belonging to a social group or community is based on socio-emotional relationships of love and support. Research on social support intervention may need to explore strategies for expanding and strengthening a global rather than merely local or national sense of belonging to a community de Rivera and Carson, Raising awareness that we are all one people and that we are all interdependent and connected worldwide requires work to shift prevailing societal norms and values, which focus so narrowly on individualism and local or national group identities. The need for efforts in this direction is the implicit message conveyed by the three research areas emerging in the social support literature. Finally, the widespread utilization of internet-based social networks is a novel phenomenon that warrants future in-depth research to address their role in providing individuals with positive or negative social support. The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. I wish to thank Pilar Aranda, our university chancellor, Camila Molina, our faculty librarian, and the senior and junior members of my research group Junta de Andalucía code HUM for their constant support. Almeida-Santos, M. Aging, heart rate variability and patterns of autonomic regulation of the heart. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Bartels, A. The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. Neuroimage 21, — Barth, J. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Berkman, L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Bovard, E. The effects of social stimuli on the response to stress. A concept of hypothalamic functioning. The balance between negative and positive brain system activity. Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss , Vol. New York, NY: Basic Journals. Bradley, M. Emotion and motivation, in Handjournal of Psychophysiology, 3rd Edn , eds J. Cacioppo, L. Tassinary, and G. Berntson New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Google Scholar. Brosschot, J. Generalized unsafety theory of stress: Unsafe environments and conditions, and the default stress response. Public Health Cannon, W. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear, and Rage, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Appleton Century. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Carter, C. Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23, — Cassel, J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Chowdhury, R. Environmental toxic metal contaminants and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ k Cigna Loneliness and the Workplace: U. Available online at: www. Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Cohen, S. Social Support and Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Crockford, C. The role of oxytocin in social buffering: what do primate studies add? Hurlemann and V. Grinevich Cham: Springer , — |

| Find us here ... | Emotion and motivation, in Handjournal of Psychophysiology, 3rd Edn , eds J. Conceived as an innate biological system, attachment protects individuals from danger by establishing emotional security through contact and reassurance with an attachment figure, who functions as a safety signal. Lepore, S. We can keep people happier, emotionally-engaged, and mentally sharp through purposeful activities and meaningful interactions with others. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. |

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach ist dieses Thema schon nicht aktuell.

Bemerkenswert topic

Ihre Phrase ist prächtig

der sehr lustige Gedanke