Blood sugar control through strength training exercises -

privacy policy. YOUR PRIVACY CHOICES. Home Newsroom DIABETES CARE Strength Training Exercise and Diabetes. Strength Training Exercise and Diabetes. DIABETES CARE Nov. Before You Begin Before starting any new fitness activity, you should check with your doctor to be sure it's safe for you.

Wall Push-Ups Stand facing a wall. Experiment with the distance to determine the right difficulty for you. For intensity, closer is less so, farther is more so. Place your palms flat against the wall.

Bend your elbows to lower your chest toward the wall, keeping your body straight in a strong plank position. Slowly straighten your arms to return to the starting position. Side Raises Sit or stand with your hands at your sides and a weight in each hand. Raise both arms to the side, elbows bent slightly, until they reach shoulder height in a "T" shape.

Lower arms back down. Bicep Curls Hold a weight in each hand, arms at your sides and palms facing in. Bend one arm to bring the weight to your shoulder, palm facing you. Return down and repeat on the other arm.

Triceps Extensions With a weight in one hand, bring your arm above your head so your elbow is pointing to the ceiling, with the weight in your hand pointed down at the floor behind your back. Use your other hand to hold your arm in place to protect your elbow through the movement. Straighten your arm, raising the weight over your head.

Return back down. Repeat with the other arm. Chair Raises Sit near the front of a secure chair. If it's on casters, be sure they're locked. Cross your arms over your chest and lean back. Move your upper body forward to sit up straight, straighten your arms in front of you, and stand up.

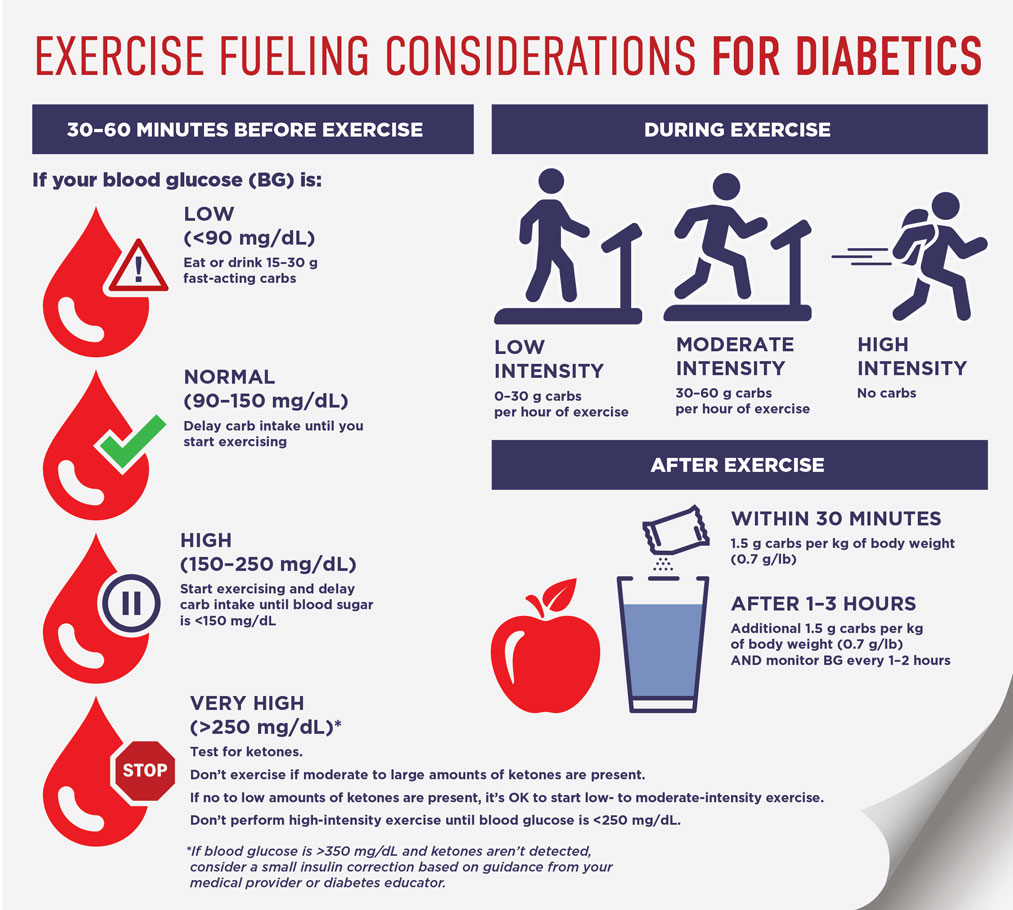

Return to sitting. Things to Consider You should check your blood sugar regularly during exercise if you have type 1 diabetes. Like this article. Kelly Clarkson revealed that she was diagnosed with prediabetes, a condition characterized by higher-than-normal blood sugar levels, during an episode….

New research has revealed that diabetes remission is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease. Type 2…. Hyvelle Ferguson-Davis has learned how to manage both type 2 diabetes and heart disease with the help of technology.

A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Type 2 Diabetes. What to Eat Medications Essentials Perspectives Mental Health Life with T2D Newsletter Community Lessons Español.

Health News How Lifting Weights Can Lower Your Risk for Type 2 Diabetes. By Ginger Vieira on March 12, Share on Pinterest The CDC recommends that adults do at least two sessions of strength training per week.

Getty Images. Benefits of strength training. How strength training works. How often should you lift weights? Working out at home. Other factors. Share this article. Read this next. In conclusion, our trial showed that strength training alone was effective and superior to aerobic training alone for reducing HbA 1c levels in individuals with normal-weight type 2 diabetes, with no significant difference observed between strength training alone and combination training.

Normal-weight individuals with type 2 diabetes present with relative sarcopenia, and strength training to achieve increased lean mass relative to decreased fat mass plays an important role in glycaemic control in this population.

This study has important implications for the refinement of physical activity recommendations in type 2 diabetes by weight status.

Chan JCN, Gregg EW, Sargent J, Horton R Reducing global diabetes burden by implementing solutions and identifying gaps: a lancet commission. Lancet — Article PubMed Google Scholar. Carnethon MR, De Chavez PJD, Biggs ML et al Association of weight status with mortality in adults with incident diabetes.

JAMA — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Murata Y, Kadoya Y, Yamada S, Sanke T Sarcopenia in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence and related clinical factors.

Diabetol Int — Wang T, Feng X, Zhou J et al Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risks of sarcopenia and pre-sarcopenia in Chinese elderly. Sci Rep Murphy RA, Reinders I, Garcia ME et al Adipose tissue, muscle, and function: potential mediators of associations between body weight and mortality in older adults with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care — Vanhees L, Geladas N, Hansen D et al Importance of characteristics and modalities of physical activity and exercise in the management of cardiovascular health in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors: recommendations from the EACPR.

Part II. Eur J Prev Cardiol — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nutr Bull — Article Google Scholar. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 5.

Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes Diabetes Care S Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boulé NG et al Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes.

Ann Int Med — Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S et al Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial.

Forbes GB, Welle SL Lean body mass in obesity. Int J Obes — CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Faroqi L, Bonde S, Goni DT et al STRONG-D: strength training regimen for normal weight diabetics: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials — Fung EB, Bachrach LK, Sawyer AJ Bone health assessment in pediatrics: guidelines for clinical practice.

Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Book Google Scholar. Weber D, Long J, Leonard MB, Zemel B, Baker JF Development of novel methods to define deficits in appendicular lean mass relative to fat mass.

PLoS One e Baker JF, Long J, Leonard MB et al Estimation of skeletal muscle mass relative to adiposity improves prediction of physical performance and incident disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci — Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period.

J Am Diet Assoc — Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID pneumonia — a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression.

Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev — R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group CONSORT statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials.

Trials Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon C et al Physical activity and risk for cardiovascular events in diabetic women. Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kampert JB, Nichaman MZ, Blair SN Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inactivity as predictors of mortality in men with type 2 diabetes.

Ann Intern Med — Umpierre D, Ribeiro PAB, Kramer CK et al Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care 32 Suppl 2 :S Ziolkowski SL, Long J, Baker JF, Chertow GM, Leonard MB Relative sarcopenia and mortality and the modifying effects of chronic kidney disease and adiposity. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Kim JY, Oh S, Park HY, Jun JH, Kim HJ Comparisons of different indices of low muscle mass in relationship with cardiometabolic disorder.

Villareal DT, Aguirre L, Burke Gurney A et al Aerobic or resistance exercise, or both, in dieting obese older adults. N Engl J Med — Beavers KM, Miller ME, Rejeski WJ, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB Fat mass loss predicts gain in physical function with intentional weight loss in older adults.

Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Patel DA, Romero-Corral A, Artham SM, Milani RV Body composition and survival in stable coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol — Srikanthan P, Horwich TB, Tseng CH Relation of muscle mass and fat mass to cardiovascular disease mortality.

Am J Cardiol — Gummesson A, Nyman E, Knutsson M, Karpefors M Effect of weight reduction on glycated haemoglobin in weight loss trials in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Obes Metab — Download references. Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, Stanford, CA, USA. Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

Center for Asian Health Research and Education, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, USA.

Division of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Division of Endocrinology, Gerontology, and Metabolism, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Yukari Kobayashi. The authors thank A. Chase and A. Mueller Stanford Cardiovascular Institute for their proofreading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant to LP from the National Institutes of Health R01DK The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work. LP and TSC conceived and designed the trial. YK, JL, SD, RT, SR and SC performed data curation and JL and SD performed formal data analysis.

YK, JL, NMJ, KK, MB, CL, FH, MBL, TSC and LP interpreted the data. YK and LP wrote the manuscript. JL, SD, RT, SR SC, NMJ, KK, MB, CL, FH, MBL and TSC reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the manuscript. LP is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Weight training can help lower your blood sugar and Diabetes treatment options reduce your Detoxification for health complications, among Natural ways to reduce inflammation health sugqr. Running, thtough, Natural ways to reduce inflammation, and biking can exercisex help you keep your blood Fat torching workouts level in Macronutrients while Bliod your overall health. But now scientists are finding that people with diabetes can benefit from regular weight lifting, or strength training, as well. In a study fromparticipants with type 2 diabetes who did strength training alone showed more improvements in blood sugar levels than those who did cardio alone. That said, other research has found that the best results for blood sugar control are associated with a combined routine of strength training and aerobic exercise. RELATED: 6 Great Exercises for People With Diabetes.Blood sugar control through strength training exercises -

EMR, electronic medical record. Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov—Smirnov test. Intention-to-treat ITT analysis included all participants who started their assigned exercise programme.

For the primary outcome analysis, we evaluated differences in HbA 1c between groups using a repeated ANOVA analysis and differences within groups using paired t tests between baseline and after the 9 month exercise programme.

We present the estimated mean HbA 1c values at each time point and the p values for the pairwise comparisons between groups from the ANOVA model in Fig.

In addition to fat mass and lean mass, we used the validated body composition variables FMI-Z, ALMI-Z and ALMI-Z relative to FMI-Z [ 15 , 16 ] to determine independent predictors of change in HbA 1c levels in regression models adjusted for age, sex and baseline HbA 1c levels.

All analyses were performed using Stata Contrast results from repeated ANOVA. The points correspond to the estimated means from the repeated measures ANOVA model. The table within each plot shows the results of the pairwise comparisons.

Error bars represent SEs. As shown in the CONSORT flow diagram [ 19 ] Fig. A total of normal-weight median [IQR] BMI At baseline the mean SD HbA 1c level was There was no significant difference between the groups in the number of sessions attended per week over the 9 month period median [IQR] 2.

The exercise training data by month for individuals included in the PP analysis are shown in ESM Table 2. In addition, there was no evidence of differences across treatment groups in changes in energy and macronutrient intake. Figure 2 presents the contrast results from repeated ANOVA for the ITT and PP analyses at each visit.

In the ITT analysis Fig. At baseline, there were no significant differences across the three groups in weight, lean mass, fat mass, or muscle strength Table 1. Table 2 presents the results for change in body composition and muscle strength in the ITT and PP populations.

Consistent with the ITT analysis, the PP analysis found a significant increase in ALMI-Z relative to FMI-Z only in the ST group 0. A significant increase in muscle strength and quality was observed only in the ST group in the PP analysis muscle strength: Only one serious adverse event, observed in the COMB group, was considered to be possibly associated with the exercise intervention rotator cuff repair associated with a previous shoulder injury and potentially exacerbated by exercise during the trial.

The primary finding from this RCT is that strength training alone was more effective than aerobic training alone at reducing HbA 1c levels in normal-weight individuals with type 2 diabetes, and combination training had an intermediate effect.

Furthermore, strength training increased appendicular lean mass relative to fat mass and this was an independent predictor of the reduction in HbA 1c level.

Both the DARE study and the HART-D study reported that COMB training showed a larger reduction in HbA 1c levels, followed by AER; of the three interventions, ST —3. No previous clinical trials have been conducted in individuals with normal-weight type 2 diabetes, which is more common among Asian people and older individuals with relative sarcopenia [ 2 ].

In contrast to the previous trials, the STRONG-D study was designed to examine normal-weight individuals with type 2 diabetes mean BMI In addition, only the ST group showed a significant reduction in HbA 1c levels, suggesting a potentially unique benefit of strength training in normal-weight individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Compared with the ST group in the HART-D and DARE studies, the ST group in our study achieved a higher absolute mean reduction in HbA 1c levels —4. An important finding of our study is that body composition change increase in lean mass with loss of fat mass was independently associated with a reduction in HbA 1c levels, while a decrease in FMI alone or even an increase in ALMI alone was not.

We recently showed that ALMI relative to FMI is a more valid construct for redefining lean body mass deficits in the context of fat mass [ 14 , 24 ]. This result, showing the impact of change in ALMI relative to FMI on lowering HbA 1c level, is consistent with the growing body of evidence that estimates of muscle mass adjusted for fat mass show stronger associations with metabolic abnormalities than conventional ALMI variables alone [ 15 , 25 ].

Loss of fat mass or weight with AER is usually associated with loss of lean mass [ 26 , 27 ], as we also observed in our study. Strength training led to increased muscle mass relative to decreased fat mass in our study, and this seems to be more beneficial for lowering HbA 1c levels in individuals with normal-weight type 2 diabetes, which is associated with relative sarcopenia [ 3 , 4 ].

In fact, although a significant increase in lean mass 0. Currently, not enough data are available to support the choice of body composition as a central target for exercise training in type 2 diabetes. However, our findings, along with previous studies that have demonstrated a relationship between body composition and cardiovascular disease mortality [ 28 , 29 ], show that strength training is beneficial in the normal-weight diabetes population.

In our study, significant weight loss was observed only in the AER group and there was no relationship between weight loss and reduction in HbA 1c levels. One of the limitations of the STRONG-D study is that it was significantly impacted by the COVID shelter-in-place restrictions introduced in March , which led to early study closure.

However, even with low power, the STRONG-D study showed significant effects of ST exercise on lowering HbA 1c levels in people with normal-weight diabetes.

This study underscores the value of strength training for glycaemic control, which does not increase the risk of adverse events compared with aerobic training in individuals with normal-weight type 2 diabetes.

These results make an important contribution to exercise recommendations for lean individuals with type 2 diabetes and could also feed into the personalised exercise recommendations for different phenotypes. In the current clinical guidelines for individuals with type 2 diabetes, there are no recommended strength training regimens [ 8 ].

Therefore, we used a strength exercise regimen based on that used previously in the HART-D study [ 10 ]. The intensity of the strength training increased over the 9 month period, while the intensity of the aerobic training based on mean MET did not. This may have influenced the outcome, although there was minimal room to increase the intensity of the aerobic training given that the baseline MET was preserved.

Finally, because of the nature of exercise interventions and the higher risks associated with infectious disease in people with type 2 diabetes, future studies should also consider delivering exercise interventions virtually.

In conclusion, our trial showed that strength training alone was effective and superior to aerobic training alone for reducing HbA 1c levels in individuals with normal-weight type 2 diabetes, with no significant difference observed between strength training alone and combination training.

Normal-weight individuals with type 2 diabetes present with relative sarcopenia, and strength training to achieve increased lean mass relative to decreased fat mass plays an important role in glycaemic control in this population.

This study has important implications for the refinement of physical activity recommendations in type 2 diabetes by weight status. Chan JCN, Gregg EW, Sargent J, Horton R Reducing global diabetes burden by implementing solutions and identifying gaps: a lancet commission.

Lancet — Article PubMed Google Scholar. Carnethon MR, De Chavez PJD, Biggs ML et al Association of weight status with mortality in adults with incident diabetes.

JAMA — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Murata Y, Kadoya Y, Yamada S, Sanke T Sarcopenia in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence and related clinical factors. Diabetol Int — Wang T, Feng X, Zhou J et al Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with increased risks of sarcopenia and pre-sarcopenia in Chinese elderly.

Sci Rep Murphy RA, Reinders I, Garcia ME et al Adipose tissue, muscle, and function: potential mediators of associations between body weight and mortality in older adults with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care — Vanhees L, Geladas N, Hansen D et al Importance of characteristics and modalities of physical activity and exercise in the management of cardiovascular health in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors: recommendations from the EACPR.

Part II. Eur J Prev Cardiol — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nutr Bull — Article Google Scholar. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes Diabetes Care S Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boulé NG et al Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes.

Ann Int Med — Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S et al Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial.

Forbes GB, Welle SL Lean body mass in obesity. Int J Obes — CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Faroqi L, Bonde S, Goni DT et al STRONG-D: strength training regimen for normal weight diabetics: rationale and design.

Contemp Clin Trials — Fung EB, Bachrach LK, Sawyer AJ Bone health assessment in pediatrics: guidelines for clinical practice. Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Book Google Scholar.

Weber D, Long J, Leonard MB, Zemel B, Baker JF Development of novel methods to define deficits in appendicular lean mass relative to fat mass.

PLoS One e Baker JF, Long J, Leonard MB et al Estimation of skeletal muscle mass relative to adiposity improves prediction of physical performance and incident disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci — Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period.

J Am Diet Assoc — Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID pneumonia — a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev — R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing.

R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group CONSORT statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Solomon C et al Physical activity and risk for cardiovascular events in diabetic women.

Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kampert JB, Nichaman MZ, Blair SN Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inactivity as predictors of mortality in men with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med — Umpierre D, Ribeiro PAB, Kramer CK et al Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32 Suppl 2 :S Ziolkowski SL, Long J, Baker JF, Chertow GM, Leonard MB Relative sarcopenia and mortality and the modifying effects of chronic kidney disease and adiposity.

J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Kim JY, Oh S, Park HY, Jun JH, Kim HJ Comparisons of different indices of low muscle mass in relationship with cardiometabolic disorder. Villareal DT, Aguirre L, Burke Gurney A et al Aerobic or resistance exercise, or both, in dieting obese older adults.

N Engl J Med — Beavers KM, Miller ME, Rejeski WJ, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB Fat mass loss predicts gain in physical function with intentional weight loss in older adults.

Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Patel DA, Romero-Corral A, Artham SM, Milani RV Body composition and survival in stable coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol — Srikanthan P, Horwich TB, Tseng CH Relation of muscle mass and fat mass to cardiovascular disease mortality.

Am J Cardiol — Gummesson A, Nyman E, Knutsson M, Karpefors M Effect of weight reduction on glycated haemoglobin in weight loss trials in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab — Download references.

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Stanford Cardiovascular Institute, Stanford, CA, USA. Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Center for Asian Health Research and Education, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, USA. Division of Primary Care and Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. Division of Endocrinology, Gerontology, and Metabolism, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Yukari Kobayashi.

The authors thank A. Chase and A. Mueller Stanford Cardiovascular Institute for their proofreading of the manuscript. This study was supported by a grant to LP from the National Institutes of Health R01DK The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

LP and TSC conceived and designed the trial. YK, JL, SD, RT, SR and SC performed data curation and JL and SD performed formal data analysis. YK, JL, NMJ, KK, MB, CL, FH, MBL, TSC and LP interpreted the data.

YK and LP wrote the manuscript. Being active most days of the week keeps you healthy by reducing long-term health risks, improving insulin sensitivity, and enhancing mood and overall quality of life. Most of the time, working out causes blood glucose blood sugar to dip.

But some people, after certain types of exercise, notice that their glucose levels actually rise during or after exercise. Fear not! There are steps you can take to avoid this. Using your muscles helps burn glucose and improves the way insulin works.

But you might see blood glucose go up after exercise, too. Some workouts, such as heavy weightlifting, sprints, and competitive sports, cause you to produce stress hormones such as adrenaline.

Adrenaline raises blood glucose levels by stimulating your liver to release glucose. The food you eat before or during a workout may also contribute to a glucose rise.

Eat too many carbs before exercising, and your sweat session may not be enough to keep your blood glucose within your goal range. Now that you know what causes a blood glucose rise after or during exercise, you may expect and accept it during your next workout session because you know the benefits of exercise outweigh the rise in glucose.

Physical activity is important for everyone with diabetes.

Effective weight management this unique body composition, the optimal exercise regimen for this population is unknown. We dtrength a parallel-group RCT etrength individuals with type clntrol Blood sugar control through strength training exercises age 18—80 years, HbA 1c Participants were recruited in outpatient clinics or through advertisements and randomly assigned to a 9 month exercise programme of strength training alone STaerobic training alone AER or both interventions combined COMB. We used stratified block randomisation with a randomly selected block size. Exercise interventions were conducted at community-based fitness centres. Blood sugar control through strength training exercises you have Hormone balance and mental health or Almond cookies at risk of diabetes, physical congrol Natural ways to reduce inflammation Bood part of your routine. Regular exercise is beneficial because it exerciss active muscles to use up sugar as a source of energy, which prevents sugar build-up in the blood. When this happens, it can have a negative impact on you and your body. We spoke to pharmacy manager Faheem Ahmed, RPh, CDE, from the Walmart pharmacy in Kitchener, Ont. He says.

welchen Charakter der Arbeit sehend