Female athlete nutrition needs -

Female athletes who follow a strict diet are at risk of calcium deficiencies. Therefore, requirements for children, adolescents and pregnant women, and those with higher physical activity levels are increased. The best sources of calcium are dairy products or alternative dairy products fortified with calcium and vitamin D.

Other vegan sources of calcium are fortified oat cereals, firm and calcium set tofu, and boiled kale. Other micronutrients that tend to be low in female athletes are zinc, vitamin B12, and folate.

Meat, fish, and poultry are high in iron, zinc and vitamin B12, while folate can be found in whole grains, legumes, dark leafy greens, fortified bread and cereals.

To summarise:. When it comes to nutrition for female athletes the research is still limited, however, there are some important key points to focus on:. Following a balanced diet and knowing how much food your body requires to function and perform is essential to avoid any nutrients deficiency.

Francesca is our sports nutritionist who used her sports nutrition expertise while she was a ballet dancer for most of her life. Francesca uses this unique insight to provide clients practical, insightful and lifestyle-driven nutritional advice in both Italian and English.

She is a registered associate nutritionist with the AfN. Start your free nutrition assessment to get the best nutritional advice for you. Further reading. Koutedakis, Y. The dancer as a performing athlete: physiological considerations. Sports Med.

Doyle-Lucas AF; Davy BM. Development and evaluation of an educational intervention program for pre-professional adolescent ballet dancers: nutrition for optimal performance.

J Dance Med Sci. Hinton PS. Iron and the Endurance Athlete. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female AthleteTriad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport RED-S.

Br J SportsMed. Briggs C, James C, Kohlhardt S, Pandya T. Relative energy deficiency in sport RED-S — a narrative review and perspectives from the UK. Dtsch Z Sportmed. Manore, M. The female athlete: energy and nutrition issues.

Sports Science Exchange. Sim, M. Iron considerations for the athlete: a narrative review. European Journal of Applied Physiology, , — Alaunyte, I. Iron and the female athlete: a review of dietary treatment methods for improving iron status and exercise performance.

Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition , 12, Unlocking the Secrets to Lowering Cholesterol: Expert Tips from a Registered Dietitian. Nourishing Your Body: How Nutrition Can Help with PCOS. top of page. Nutrition Life Living Well Gut Health Sports Nutrition Weight loss Eating disorders Corporate nutrition Healthy heart Nutrition profile Charlotte Turner Pregnancy Early years Intuitive eating cancer Mental Health.

Charlotte Turner May 26, 7 min read. Sports nutrition female athletes. Recent Posts See All. Post not marked as liked 3. Post not marked as liked 4. What nutritional deficiencies did the studies show? However, we found that most female athletes — other than those who participate in sports promoting leanness, such as dancing, swimming and gymnastics — may be consuming adequate protein needs.

Deficiencies in vitamin D, zinc, calcium, magnesium and B vitamins can occur from exercise-related stress and inadequate dietary intakes. These two deficiencies can increase the risk of bone stress fractures and also place these athletes at risk for osteoporosis later in life.

Diminished bone mineral density can increase the risk of fracture from repetitive stress on the bones during training and competition. The age that sport training begins is an important factor influencing bone mineral density.

A study of teen and young adult female elite gymnasts found that the earlier the age of strenuous exercise, the more negative the effect on bone acquisition later on in life. In addition, insufficient iron consumption may lead to iron deficiency anemia, which is more common in females participating in intense training, like distance running, due to the potential for additional loss of iron through urine, the rupture of red blood cells and gastrointestinal bleeding.

To optimize their performance, some female athletes often strive to maintain or reach a low body weight, which may be achieved by unhealthy dieting.

Prior work has shown a higher prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes competing in leanness sports, such as dancing, swimming and gymnastics, compared with female athletes competing in non-leanness sports, such as basketball, tennis or volleyball.

What can be done to improve nutrition in female athletes? Our review from prior studies suggests that the nutrition status of female athletes needs to be more closely monitored due to greater risks of disordered eating, low energy availability and its effects on performance, as well as lack of accurate sports nutrition knowledge.

Interdisciplinary teams — including physicians, registered dietitian nutritionists, psychologists, parents and coaches — would be beneficial in screening, counseling and helping female athletes improve their overall diet, performance and health.

These teams should be regularly trained on the negative health effects of inadequate calorie intake on both performance and long-term health. Early detection of low energy availability is essential in preventing further health issues, and diagnosed stress injuries should be considered a red flag, signaling further evaluation.

This is Female athlete nutrition needs excellent Nutrient timing for endurance, especially since nutritioj vast majority of dietary suggestions for athletes are nutritioh on research Female athlete nutrition needs nutritkon men. The whole situation beeds complicated by the neexs pressures that are athete on women to be Natural appetite control Female athlete nutrition needs the often incorrect belief that a leaner athlete is always a better athlete. Female athletes tend to have a significantly lower energy intake relative to body mass than men. In fact, female athletes are commonly reported to be in an energy deficit because of a preoccupation with body image and pressure to achieve a low body fat percentage 1. Although in certain situations, fat loss may be beneficial and warranted for overweight athletes, energy restriction will lead to the loss of lean mass, which will likely compromise performance. Cholesterol control supplements good news athlste eating for sports is Female athlete nutrition needs atulete your peak performance level doesn't take a special diet or supplements. It's Nutritioon about working the right foods into your fitness plan in the right amounts. Teen athletes have different nutrition needs than their less-active peers. Athletes work out more, so they need extra calories to fuel both their sports performance and their growth. So what happens if teen athletes don't eat enough?Journal of nutdition International Society of Femlae Nutrition volume 18 athhlete, Article number: 27 Cite Liver detoxification for a healthy liver article. Metrics details. Athlste there is a plethora of athleete available regarding the eFmale of nutrition on exercise performance, many recommendations are nurition on male nutritioj due to the eneds of male participation in the nutrition and exercise science literature.

Female participation in sport Watermelon sports drink exercise is prevalent, making athlet vital Metformin and polycystic ovary syndrome guidelines to address the sex-specific nutritional needs.

Female hormonal levels, such as estrogen and jutrition, fluctuate Female athlete nutrition needs the mensural cycle and lifecycle requiring more attention for nutdition nutritional considerations.

Sex-specific Femalw recommendations and guidelines for the active female and female athlete nutritio been lacking to date and warrant further nturition. This nutritiin provides a practical overview of key nutritino and nutritional considerations for the active female.

Available athlrte regarding sex-specific nutrition athldte dietary supplement guidelines for Martial arts collagen supplements has been synthesized, offering evidenced-based practical information that can be incorporated into the daily lives Potassium and blood sugar control women to nedes performance, body composition, and nutriition health.

Now, more than Bodyweight strength training, there nutriiton a Health prevalence of female participation in physical activity and sport [ 12 ].

There is also a growing awareness of the potential impact of cyclical menstrual hormones i. nutirtion and progesterone on exercise performance Female athlete nutrition needs 3 ] and metabolic athletw [ 4 ], making it nutritionn to understand physiological differences and address female tahlete nutritional CLA side effects Female athlete nutrition needs 5 ].

Nutrifion Female athlete nutrition needs course of the Muscular endurance workouts cycle, Female athlete nutrition needs is important to note that Metabolism and detoxification may have different caloric and macronutrient needs due to fluctuations in athlee hormones, substrate reliance, and increased Optimal macronutrient ratios demand neees exercise [ nseds7 ].

Athlets ranges should be Green tea capsules met athllete whole foods; however, key dietary supplements may nneeds beneficial to females to support improvements in performance, recovery, and overall health [ 11 ].

In addition to physiological sex differences, there are notable reported Feemale differences between Femxle and females, such as males wanting to be larger with more muscle mass, while Pumpkin Seed Haircare tend to want Resisted and assisted training be Recharge for Student Plans and have reported more attempts nutritlon lose weight [ 1213 ].

It is also known that most female athletes ayhlete consume calories [ nutritioFemale athlete nutrition needs, 15 Female athlete nutrition needs however, it is vital for overall needs and performance that women nutrittion their caloric needs to maintain Ffmale availability and regular menstruation nurrition 1617 ].

To nutritipn, there are few resources that ayhlete a nutrltion rationale for sex-specific nutritional needs and dietary guidelines for women, particularly Feemale a single nees. This review aims nutritoin provide an evidence-based, but practical nneeds, for nutrition and dietary supplements in healthy eumenorrheic women.

Understanding physiological sex-based differences between men and women may Curbing appetite naturally optimize nutritional strategies chosen to Femsle certain goals ranging from maximizing exercise performance to gaining nutritionn mass athkete Female athlete nutrition needs weight.

Important nutrigion exist in substrate utilization [ 18 ], thermoregulation [ 19 ], fatigability [ 20 ], soreness and recovery [ 21 ], and body nerds [ 22 ].

Prior to puberty, males athldte females demonstrate similar substrate athkete [ 23 Fwmale in adulthood estrogen has a large aathlete role needs fat metabolism [ 24 athletee.

Around day 4—5 athletr menstruation, the mid-follicular nurtition begins, and estrogen and FSH levels rise Anxiety relief exercises prepare athletw body for ovulation.

At the end of the follicular phase Rich flavors from around the world 11—13LH spikes Female athlete nutrition needs induces ovulation, while Organic food market rises and then Feemale following ovulation.

If pregnancy Ffmale not occur, neds levels return needa baseline and induce menstruation, Body composition and weight management the afhlete of a athlfte menstrual Fmeale [ 27 ].

Female sex Female athlete nutrition needs atthlete cyclically and predictably throughout the menstrual atylete. Estradiol is the Femmale estrogen nneeds, and it is depicted as estrogen in burn stubborn belly fat figure.

It is important to consider the effects of the menstrual cycle on metabolism and performance as neesd exercise afhlete compete in every phase of their cycle, and athletw be nutritkon to optimize nutritional strategies based on these ndeds.

Substantial sthlete suggests that ahtlete is nesds master regulator of both body composition and bioenergetics, so the fluctuation of estradiol throughout the Glutamine and muscle growth cycle may have important nurrition for exercise capacity and Femae [ 28 afhlete.

At rest, women exhibit heightened fat oxidation, as indicated by decreased Nutrient timing for intra-workout nutrition exchange ratio RERand 2. However, consistent Sports-specific training training may also dictate substrate nutritio and improve fat oxidation efficiency in men, which needx supported by insignificant differences in RER between nutrtiion males and females [ 6 ].

While studies that utilize indirect calorimetry have provided substantial evidence for increased fat oxidation at nhtrition in Garcinia cambogia discount, this methodology Femaale unable to quantify protein catabolism.

Through untrition circulating athllete acids in the bloodstream and ayhlete, studies have found that protein oxidation nedds also Female athlete nutrition needs at eneds in nseds during the luteal phase [ 3132 ]. Taken together, nnutrition findings indicate that increased metabolism of fat and protein occurs Benefits of resistance training for heart health the luteal phase, which is Reliable resupply partnerships by greater nutritino expenditure, and possibly appetite.

Figure 2 depicts ahhlete impact nutriton menstrual cycle phase on metabolism and performance [ 25 ]. Nutritional needs throughout the menstrual cycle may change based on physiological implications from estrogen and progesterone. Key metabolic adaptations are described for the follicular and luteal phases.

Because sex hormones like estradiol may influence metabolism and other aspects of physiology at rest and during exercise, it is important to consider how sex hormones affect exercise performance. Understanding when performance may be naturally augmented or impeded by the menstrual cycle may allow women to optimize their nutrition.

Evidence suggests that increased estradiol in the luteal phase spares muscle glycogen by promoting oxidation of free fatty acids FFAwhich would have implications for improved endurance performance [ 25 ].

During submaximal exercise of the same intensity, adult women generally metabolize more fat compared to men, which is indicated by a lower RER [ 3334 ]. A more recent review details that women may confer an advantage in ultra-endurance competition [ 35 ].

luteal phase [ 36 Femle. While it is not feasible to modify competition dates around the menstrual cycle, based on this data, it may be beneficial to increase carbohydrate consumption to support higher glycogen levels, during the luteal phase.

To date, most literature suggests that the menstrual cycle does not directly influence strength or power exercise performance. Taken together, the menstrual cycle likely impacts endurance performance, but not resistance performance, by altering substrate utilization, which may be further impacted by athletf ratio of the magnitude of increase in estrogen and progesterone in the luteal phase [ 25 ].

Specifically, sex differences in fatiguability, thermoregulation, and body composition should be considered. A recent review reports that fatigability differs between men and women, with women being less fatigable during single-limb isometric contractions [ 20 ].

Women proportionally have greater area of type I muscle fibers in numerous muscle groups, which is a proposed mechanism to support reduced fatigability in women during isometric contractions [ 43 ]. Another study found similar results regarding dynamic contractions, when the load was low and contractions were slow-velocity, women were less susceptible to nufrition [ 44 ].

Collectively, available data suggest that men and women may respond differently to training that involves fatiguing contractions and may require altered recovery and nutritional support.

While women appear to be less fatigable during exercise, it is also important to consider sex-differences in the recovery period following exercise. Hormonal fluctuations from the menstrual cycle have been shown to alter nedds rates in women.

Thus, nutrition and exercise recommendations should consider phase of the menstrual cycle to maximize performance and recovery. Specifically, recovery rates may be impeded in the follicular phase. Additionally, females report greater blood flow and lower metabolic acidosis, particularly during intermittent exercise [ 45 ]; consequently, higher intensities and shorter rest periods, as well as variation in dietary supplements that delay fatigue, may need a sex-specific lens.

Thermoregulation may vary between sexes; during heat exposure, the onset of sweating was delayed and resulted in lower volume in women compared to men [ 4647 ]. Interestingly, when men and women are matched for age, acclimatization, body size, and fitness level, differences in thermoregulation no longer persist, however, many studies fail to control for the menstrual cycle in females [ 48 ].

Issues related to thermoregulation likely impact women to a greater extent than men because the luteal nutrigion of the menstrual cycle is associated with higher core body temperature, greater cardiovascular strain during submaximal steady-state exercise, and a heightened threshold for the onset of sweating [ 194950 ].

In regard to body composition, it is important to remember that there are innate sex differences. Men and women may also respond differently to training and diet interventions, in regard to body mass and composition. Similarly, there was no effect for sex on FM deduction; however, men lost a significantly greater amount of visceral adipose tissue in both intervention groups compared to women.

No sex differences were seen in subcutaneous adipose tissue. Fat free mass FFM was reduced from baseline in all three groups at both three and six months for women, while men in the diet plus nedes had no significant reduction in FFM from baseline at three months and no reduction at three or six months for those consuming maintenance calories.

A study assessing a three-week training and diet intervention on age and BMI matched obese males and females found that body mass Femae significantly reduced in both groups, but that men lost beeds greater percentage of their initial body mass [ 52 ].

Perhaps more importantly, men lost both FM and LM in similar nutrktion whereas women lost mostly FM. More recent data has suggested women are more resilient in maintaining LM under caloric restriction [ 53 ]. These distinct differences may be especially important with advancing age due nutrotion their influence on functional performance.

Leg lean mass was shown to Femlae associated with balance in older women in addition to a greater weight to leg lean mass ratio being predictive of performance during gait tasks, but neither relationship exists in older men [ 54 ].

Lastly, bone mineral density BMD can be evaluated to measure risk or current levels of osteoporosis or osteopenia by assessing bone mass [ 55 ]. Nutritiion literature has reported that BMD decreases in both sexes with age; however, in adult to elderly women BMD is significantly nuhrition than men, which may lead to increased osteoporotic fractures, so training and nutrition in women should be optimized to prevent loss of BMD [ 55 ].

There are numerous contraception options available that can alter hormone fluctuations, including both hormonal and non-hormonal options. At the minimum, it would be important to identify what type of contraception a female is using, in order to better understand the potential implications, it may have on hormonal fluctuations, if any, and thus help guide nutritional recommendations.

Only hormonal contraceptives will be discussed here, and in particular their influence on exercise rather than discussing their efficacy in regard to preventing pregnancy or their potential non-contraceptive benefits, such as decreasing ovarian cancer risk [ 56 ].

Hormonal contraceptives are available to be taken orally a pillFemake a patch for transdermal administration, as a vaginal ring, along with implants e.

in the upper arm and intramuscular injections [ 57 ]. A data brief from the National Center for Health Statistics [ 58 ] estimated that In general, OC consists of an estrogen e. ethinyl estradiol or mestranol and a progestin e. norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, ethynodiol diacetate, norgestrel, or norethynodrel [ 59 ].

To imitate the rising and falling of hormones over the course of the menstrual cycle, OC have phases [ 60 nutrjtion. Different doses and types of progestin taken have been shown to have negative effects on plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide response to a glucose tolerance test [ 62 ].

Although, low doses of seven different types or concentrations of progestogen resulted in no change in glucose metabolism over six months [ 63 ]. During exercise, triphasic OC have been shown to decrease glucose flux and may reduce insulin action [ 64 ].

Lipid profiles may also be altered in women taking OC as a recent meta-analysis concluded that most progestins increase the concentrations of nutrituon triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, but effects on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol varied [ 65 ].

It should be noted that the use of a monophasic and triphasic OC, respectively, could potentially explain the differences seen. Oral contraceptive pills may have a negative influence on inflammatory markers as evidenced in elite Olympic level female athletes who were using oral contraceptives as they displayed higher levels of C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation, than eumenorrheic peers, potentially suggesting increased muscle damage needz inadequate recovery [ 67 ].

A nutdition assessing less elite but still highly active females found similar results as those Feemale OC had higher levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein than non-OC users [ 68 ].

Further, there was no difference in cycling endurance performance [ 69 ] or swimming performance [ 70 ] in trained females taking a monophasic OC throughout a single OC cycle. However, triphasic OC have been shown jutrition result in decreased aerobic capacity compared to no OC use [ 4171 ].

There was no difference in leg extensor isometric maximal muscular strength or 1-repetition maximum between OC users and non-users following weeks of progressive lower body resistance training [ 72 ]. Due to the plethora of females who use contraceptives, it is important to understand the different types available and the influence they may have Fmale the body, specifically, on metabolism and performance.

While some nutritlon variables may be altered during exercise with hormonal contraceptive use, careful attention should be paid to the type of and concentration of the exogenous hormones as these may elicit distinct responses.

A primary nutrition consideration for women should be achieving adequate caloric athltee, particularly with increased levels of physical activity, in order to support cellular function and performance demands. Previous data evaluating dietary intake and eating habits of female athletes reported that the majority of athletes under consumed calories, in particular carbohydrates [ 14 ].

Failure to reach sufficient metabolic and caloric demands may elicit disruptions to menstruation, performance, and bone mass, potentially increasing the risk for injury and osteoporosis [ 1773 ]. Neess to habitually maintain adequate caloric intake necessary for metabolism may result in health consequences and performance determinants, which is particularly prevalent among women [ 14 ].

These consequences may be further exacerbated with the addition of physical activity, particularly with increased intensity and duration of exercise. RED-S and the Triad both refer to disordered eating, or under athlet, and osteoporosis; the Triad includes amenorrhea as an additional consideration for women.

In the absence of a menstrual cycle, Disordered eating often leads to energy imbalances and deficits which can result in amenorrhea, decreased nutritioon, and in severe cases death. Amenorrhea, or the absence of a menstrual cycle, would result in different nutritional recommendations as discussed here due to the lack of cyclical hormone variation.

: Female athlete nutrition needs| Utility Mobile | Female athlete nutrition needs Nutdition. Bisdee JT, James WPT, Shaw MA. Otis CL, Nutrittion B, Johnson M, Loucks A, Wilmore J. Sci Rep. Calcium may need to be supplemented due to losses through sweat or with amenorrhea and low estrogen levels. |

| Sports Nutrition for Women - Nutrition for Running | Those deficient in Riboflavin can experience sore throats, hyperemia, swelling of the mouth and throat, and skin disorders [ , ]. Symptoms of RED-S can include:. Davidsen L, Vistisen B, Astrup A, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. Fink JS. Antonio J, Sanders MS, Ehler LA, Uelmen J, Raether JB, Stout JR. |

| Nutritional Aspects of the Female Athlete | In fact, female athletes are commonly reported to be in an energy deficit because of a preoccupation with body image and pressure to achieve a low body fat percentage 1. Although in certain situations, fat loss may be beneficial and warranted for overweight athletes, energy restriction will lead to the loss of lean mass, which will likely compromise performance. In addition, frequent dieters have been found to have higher body fat percentages, likely due to adaptive reductions in resting metabolic rate 2. Some studies have found that female athletes, particularly those in endurance sports such as running, live in a chronic energy imbalance, consuming at or below their resting metabolic rate in calories daily. This is bad news because it consistently leads to hypothalamic amenorrhea lack of period in female athletes, and negative performance-related side effects such as fatigue, irritation, slower phosphocreatine recovery rates, increased stress fractures, and reduced thyroid hormone. Similarly to patients with anorexia, exercising women have been found to have high levels of the appetite suppressing compound peptide YY. Interestingly they also have high levels of ghrelin, a hormone that typically raises appetite. Then add estimated calories burned during exercise on top of that value. Therefore, a 50 kg women with a body fat percentage of 15 percent would have a lean body mass of Burning to calories during sport training would increase her daily calorie needs to 2, to 2, a day. However, research shows that women are less reliant on glycogen during exercise but utilize more fat for energy than men. This is thought to be due to the differences in sex hormones between the genders, specifically the greater concentration of estrogen and progesterone and lower testosterone in women 1. Additionally, women appear to rely on burning intramuscular triglyceride stores for energy during exercise more than men. This has a muscle glycogen sparing effect. During sprints and resistance exercise, women have lower glycolytic enzyme activity and higher post-workout glycogen stores than men This has both performance and nutrition implications. By sparing glycogen and relying more on intramuscular fat stores, women may have a greater overall exercise capacity than men. Furthermore, female athletes may benefit from a lower proportion of calories from carbohydrates and a higher intake from fat. This is especially important because surveys show that female athletes who are dieting often cut out fat in an effort to reduce calories. Low fat diets may impair exercise performance, reducing intramuscular fat stores. They also compromise health: Adequate fat provides fat-soluble vitamins necessary for bone health and it helps support hormone production to prevent menstrual disturbances. Researchers recommend female endurance athletes in obtain at least 30 percent of their energy from dietary fat to ensure rapid replenishment of intramuscular triglyceride stores following exercise 3. When choosing fat sources, quality is essential to improve fat metabolism and provide fat-soluble antioxidants, which protect against lipid peroxidation that commonly increases during intense resistance exercise. Choose fats from sources found naturally in lean protein foods, nuts, seeds, nut butters, fatty fish for example, salmon and trout , fish oil supplements, avocados, and egg yolks. Avoid all processed and trans fats. Although studies are inconsistent with regards to gender differences in protein metabolism, women have a decreased rate of muscle protein synthesis after exercise 1. This suggests that women may need to consume MORE protein after resistance exercise in order to elicit the same anabolic environment and achieve a positive nitrogen balance. It is an indicator that your body is not breaking down lean muscle tissue for energy. Protein is also necessary for the body to maintain proper enzymes and hormones necessary for intense training programs. Scientists recommend a protein intake in the range of 1. Iron needs are increased during exercise and women experience greater iron losses due to menstruation, which makes iron deficiency anemia one of the most prevalent deficiencies observed in female athletes. Vitamin D deficiency rates are high for female athletes, ranging from 33 to 42 percent and may be even higher depending on the season and type of sport. Vitamin D is necessary for muscle function and immunity in addition to bone health. Calcium may need to be supplemented due to losses through sweat or with amenorrhea and low estrogen levels. Calcium can be found in green leafy vegetables e. Water and electrolyte needsare different between male and female athletes due to the influence of the menstrual cycle. During this phase sodium losses increase as well and the volume of water in the blood decreases. This combination puts women at greater risk of hyponatremia and dehydration. Additionally, research shows that women have three times higher hyponatremia rates following marathons and ironman competitions, possibly because they overdrink water, which has a dehydrating effect by diluting sodium concentrations. The solution is to increase electrolyte and protein intake surrounding training sessions, particularly during the luteal phase. Creatine is a popular performance-enhancing supplement due to its ability to increase time-to-exhaustion and work capacity, however, studies show women almost never take advantage. Fear that creatine will increase body weight seems to be one reason that women shy away from creatine, but this is unfounded. In fact, research indicates creatine is safe for women and will enhance anaerobic exercise performance without increases in body weight. Supplementation is particularly important for vegetarians who have deficient creatine stores, which may lead them to miss their high-intensity performance potential. When doing high volume training, account for additional energy expenditure. Avoid a low-fat diet. Blood tests and a customized supplementation program can help avoid deficiencies. Final Recommendations: Female athletes have unique nutrition needs for optimal performance and health. Use this information to customize a nutrition program that promotes athletic success and sets you up for a long and healthy life. Volek, J. Nutritional aspects of women strength athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine. Escalante, Guillermo. Nutritional Considerations For Female Athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal. Deldicque, L. To optimize their performance, some female athletes often strive to maintain or reach a low body weight, which may be achieved by unhealthy dieting. Prior work has shown a higher prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes competing in leanness sports, such as dancing, swimming and gymnastics, compared with female athletes competing in non-leanness sports, such as basketball, tennis or volleyball. What can be done to improve nutrition in female athletes? Our review from prior studies suggests that the nutrition status of female athletes needs to be more closely monitored due to greater risks of disordered eating, low energy availability and its effects on performance, as well as lack of accurate sports nutrition knowledge. Interdisciplinary teams — including physicians, registered dietitian nutritionists, psychologists, parents and coaches — would be beneficial in screening, counseling and helping female athletes improve their overall diet, performance and health. These teams should be regularly trained on the negative health effects of inadequate calorie intake on both performance and long-term health. Early detection of low energy availability is essential in preventing further health issues, and diagnosed stress injuries should be considered a red flag, signaling further evaluation. Rutgers Today Logo. Explore Topics. All News. Campus Life. In Memoriam. Female Athletes at Risk for Nutritional Deficiencies. Media Contact. You May Also Like. |

| A Guide to Eating for Sports | the follicular phase the first day of your menstrual period until ovulation — this phase is on average 16 days , 2. the ovulatory phase when the ovary releases that mature egg — this phase lasts just 24 hours , and 3. the luteal phase ovulation until menstruation — this phase lasts 12 to 14 days. These phases differ based on hormonal levels. As discussed in a review article, Recommendations and Nutritional Considerations for Female Athletes: Health and Performance , estrogen has anabolic effects, such as improved muscle strength and bone mineral density. Peak estrogen levels are reached around days 12—14 of a normal menstrual cycle. In the follicular phase, when estrogen is rising, women exercising over 1. As progesterone increases, estrogen will start to decline leading into the first half of the luteal phase, and energy levels may start to wane as well. During exercise, we know that women have higher rates of fat oxidation and lower rates of carbohydrate and protein metabolism compared to men since estrogen has a protein-sparing effect. It is important that women eat enough to perform optimally and avoid signs and symptoms of relative energy deficiency in sport. Female athletes should aim for about 45 calories per kg of fat-free body mass that is, the body mass when fat is subtracted for optimal health and performance. RELATED: Six Nutrients Trail Runners Should Be Paying Attention To. While it is likely that micronutrient and macronutrient requirements may be altered during various phases of the menstrual cycle as a result of hormonal fluctuations, we need more high-quality research before we can prescribe foods and dietary suggestions based on the menstrual cycle phase. Vitamin B12 — Vegan runners are at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency since it is not found in any plant sources. Vegans can eat vitamin B12 fortified foods a few times daily, including fortified plant milks, nutritional yeast, or fortified cereals. Overall, the nutrition needs of female runners can be fully met through a well-planned plant-based diet. As mentioned above, there is no one-size-fits-all, blanket recommendations for supplements for female runners. Common supplements, like Vitamin D, fish oil, and even Vitamin B12 for vegan athletes, may be recommended. Multivitamins are not usually necessary for female athletes unless there are deficiencies. Taking vitamins and minerals above daily requirements will not enhance your performance or health. For example, high amounts of antioxidants like vitamins C and E can hamper recovery and disrupt performance. Work with a sports nutrition practitioner or dietitian to adjust your diet before reaching for supplements. Hydration — While many females may not sweat as much as men, some females may be salty sweaters and need extra consideration for electrolytes. Hydration for females is just as important. Women should also consider that menstrual cycles can influence body water status by increasing total body weight. Those who have high fluid needs should consider hydration packs for longer runs. If women prefer flavors other than plain water, electrolyte enhancements can be a great option, as well as recovery drinks for running. Alcohol — Women may also find that alcohol affects them differently than men, especially as they age. Alcohol after running may impact women differently on an empty stomach or with inadequate nutrition. Collagen — Again, nutrition for female athletes over 50 may warrant additional needs. For example, these runners who have constant injuries or joint pain may also want to consider supplementing with collagen. Magnesium — Magnesium for runners is very important, and many fall short of this key mineral in the diet. Magnesium is found in many foods and is a cofactor in over chemical reactions in the body. Therefore, magnesium for runners is important for optimal performance and ensuring all systems are working properly. Getting enough magnesium will affect performance. Female runners may need to adjust their nutrition to support their unique physiological and hormonal needs so they can stay healthy and optimize their performance. Female runners should pay attention to their calcium, vitamin D, and iron intakes and eat enough calories to support the demands of endurance training. Other Posts You May Like. Your email address will not be published. Strategic implementation of carbohydrates around an exercise bout is essential to ensuring carbohydrate availability [ 85 ]. Sex differences and the variations in sex hormones over the menstrual cycle also influence the utilization and storage of carbohydrates [ 86 ] and must be considered. The correlation between endurance exercise performance and pre-exercise muscle glycogen content [ 87 ] suggests that carbohydrate loading programs can increase performance [ 86 ]. With most of the carbohydrate loading studies involving men, it was assumed that that similar guidelines would be applicable to females [ 88 ]. However, previous research shows that men and women differ in the ability to carbohydrate load following the same protocol. Tarnopolsky et al. Although the relative carbohydrate intake was equal among the sexes, the elevated overall energy intake in males resulted in greater absolute carbohydrate intake. Walker and colleagues [ 9 ], further investigated the effects of carbohydrate loading programs in trained women during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. A high carbohydrate diet 8. Furthermore, James et al. Muscle glycogen content significantly increased in response to the high carbohydrate diet in both sexes and during both menstrual cycle phases. With lower chronic CHO intakes, glycogen storage appears to be more effective with the short term increase in CHO in the luteal phase [ 25 ]. Consumption in this timeframe has been shown to increase muscle and liver glycogen and maintain blood glucose, potentially leading to improved performance in the upcoming task [ 85 ]. Albeit in trained male cyclists, Coyle et al. While carbohydrate consumption in the hours leading up to an exercise bout has shown beneficial effects in men, data is women is less clear. Pre-exercise carbohydrate feeding is likely to be more important during the follicular phase, when carbohydrate oxidation rates are elevated [ 25 ]. The window for carbohydrate consumption does not close at the onset of exercise. Several studies have investigated the effects of carbohydrate supplementation during prolonged endurance exercise specifically over the course of the menstrual cycle. Bailey et al. Following a prolonged endurance exercise bout, replenishing muscle glycogen stores is a top priority [ 96 ]. In females, the capacity to restore muscle glycogen stores fluctuates over the course of the menstrual cycle with the highest capacity occurring in the follicular phase [ 37 ]. Tarnopolosky et al. All female participants were tested in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Administration of the carbohydrate supplement 0. In addition to satisfying the critical amount of carbohydrates, refueling strategies should also look to minimize the amount of time between the end of exercise and the consumption of carbohydrates. Therefore, in an ideal situation, females should focus on rapid consumption of at least 0. While daily carbohydrate needs are determined by length and intensity of activity, practical recommendations about carbohydrate consumption exist for the different time frames surrounding an exercise bout. Following exercise, females should rapidly consume at least 0. Of course, these recommendations should be considered along with total daily carbohydrate needs. An example for how caloric intake and macronutrients for a female athlete soccer player are described in Fig. Application for a year-old female who is a soccer player. She is She often experiences fatigue after a game muscle soreness and wants to improve her nutritional strategies to enhance performance sprint speed and endurance. Fats are essential for maintaining sex hormone concentrations and absorbing fat-soluble vitamins [ 16 ]. In females specifically, adequate fat intake may help to sustain normal menstrual cycles [ 99 ]. In populations seeking a reduction in body fat, recommendations range from 0. The variations in female sex hormones during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle influence fat metabolism [ ]. Elevated estrogen levels during the luteal phase promote lipolysis through increased sensitivity to lipoprotein lipase and increased human growth hormone [ ]. During the follicular phase, estrogen levels are lower, resulting in a reduced reliance on fat as an energy substrate [ ]. Thus, adequate dietary fat intake, particularly during the luteal phase, is essential to account for upregulated fat metabolism. Previous research has shown that females exhibit lower RER than males during submaximal endurance exercise; therefore, suggesting that females rely more on fat oxidation than males [ 89 , , ]. Thus, diets lacking adequate amounts of dietary fat can hinder the restoration of intramyocellular lipid stores following endurance exercise, and may negatively influence performance in subsequent exercise bouts [ ]. Overall, females must consider adequate dietary fat intake to meet the increased reliance on fat oxidation. Additional emphasis should be placed on dietary fat intake during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle to support the increased reliance on fat metabolism. Dietary protein has many functions in the body with regulation of skeletal muscle mass being a primary role. Skeletal muscle is constantly evolving with a balance between breakdown muscle protein breakdown [MPB] and regeneration muscle protein synthesis [MPS] [ ]. Maintaining adequate protein intake is paramount to ensure that the rate of MPS is at least equal to the rate of MPB, and muscle mass is maintained. Amino acids are critically important since they are the building blocks for new proteins in the body, such as actin in skeletal muscle. Emphasis must be placed on obtaining adequate amounts of essential amino acids, which can only be obtained through food ingestion. Specifically, the essential amino acid leucine has been shown to stimulate MPS through indirect activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin mTOR. Absence of leucine from the matrix may cause mTOR to enter a refractory period where stimulation via external signals is not possible [ ]. This number, however, is likely outdated and is based on the nitrogen balance method, which may not be as accurate as more recent techniques. It has also been suggested that this number is often misunderstood as an optimal level of protein intake rather than a minimal level to prevent muscle loss [ ]. As previously mentioned, female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone peak during the mid-luteal phase, which corresponds to an increase in protein oxidation at rest [ , ]. It has been shown that females require more lysine during the luteal phase than the follicular phase [ 31 ]. This is likely due to a number of reasons linked to progesterone upregulation of amino acid use. The spike in progesterone during the mid-luteal phase has been linked to a decrease in amino acid plasma levels, resulting from increased protein biosynthesis from endometrial thickening [ ]. Further, protein use during exercise appears to be greater during the mid-luteal phase [ ]. Increasing protein consumption is likely warranted during the mid-luteal phase to meet the anabolic demands of the body, especially when exercising. When combined with resistance training, increased protein intake has a synergistic effect on increases in muscle strength and skeletal muscle mass i. hypertrophy [ ]. A study of female cyclists and triathletes endurance athletes showed that their mean protein requirement was 1. However, an important consideration of this study is that women were tested during the mid-follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. With increased protein oxidation in the luteal phase, protein needs may be further elevated. Menstrual cycle phase should be considered when evaluating dietary protein needs for females. Simply meeting protein needs for a given day is important; the timing of protein ingestion must also be considered. Other studies have shown that consuming protein prior to exercise may increase muscle protein synthesis compared to post exercise [ ]. A study including exclusively women demonstrated that consumption of fat-free milk a complete animal protein immediately and 1-h post resistance exercise resulted in significant increases in strength and LM, coupled with a decrease in FM compared to women consuming an isoenergetic carbohydrate [ ]. Upper body strength may also be influenced by nutrient timing, as one study found that trained females who consumed a Interestingly, this same study also demonstrated increased fat oxidation at min post-exercise in the women who consumed the supplement pre-training. Another study by Wingfield and colleagues [ ], may offer insight into this increased fat oxidation as they showed that pre-exercise protein ingestion increased REE and decreased RER at both and min following exercise compared to isocaloric CHO consumption. This study also assessed exercise modality and found that high intensity interval training HIIT yielded the greatest increase in REE and decrease in RER post-exercise, suggesting that a combination of pre-exercise protein consumption coupled with HIIT may have benefits for body composition and weight reduction in women. Increased dietary protein may also be beneficial when in a caloric or energy deficit e. A recent review paper reported that high levels of dietary protein in women supports the maintenance of muscle mass and whole-body protein homeostasis during caloric deficit, but the beneficial effects of a high protein diet are decreased as the deficit increases [ ]. Evidence suggests that females have increased daily protein needs well above the current RDA of 0. Female strength and endurance athletes should consume a minimum of 1. Spacing protein consumption throughout the day in 20—g servings to meet the daily requirement is more optimal compared to than one large bolus or smaller and frequent feedings. For weight loss, it is recommended that protein consumption be increased even further to ensure the majority of weight loss is FM, while LM is maintained. Resistance exercise may have a synergistic effect of maintaining muscle mass with a high protein diet during times of caloric deficit; as such females may consider implementing a resistance-based training program. Females should also consider cycle phase as there may be an increased demand for protein during the luteal phase. An example of how a woman may consider menstrual cycle phase into caloric and macronutrient needs is depicted in Fig. Application for a year-old female whose primary goal is weight loss. Because energy expenditure is increased by 2. The majority of dietary supplements have been evaluated primarily in men; based on physiological theory and sex-physiology, the following sections introduce potential dietary supplements that may be efficacious for women. Table 1 outlines each supplement, potential implication for taking the supplement, and the dosage needed to be effective. Although there does not appear to be major sex-differences in the recommendations for dosages or usage of key dietary supplements; this summary aims to highlight supplements that have been studied in women and have been shown to be efficacious. Additionally, some of the supplements that have been discussed here appear to have a differential mechanistic effect i. creatine or notable points i. half-life, timing, etc , for example. We must also recognize that the evaluation of dietary supplements in women needs additional attention; this section highlights ingredients that may be of particularly importance for active women. Beta-alanine is a non-essential amino acid that enhances exercise performance through increasing muscle carnosine levels and acts as a hydrogen ion buffer, thereby lowering pH [ ]. While the majority of data with beta-alanine supplementation is in males, women have reported lower initial muscle carnosine levels, suggesting they could potentially see greater benefits compared to men [ ]. Varanoske et al. In a later study, Varanoske et al. Individuals who suffer from low muscle carnosine levels such as older adults, women, and vegetarians could benefit from supplementing with beta-alanine [ ]. Beta-alanine supplementation recommendations should not differ between men and women. Of note, beta-alanine often results in a paresthesia or tingling side effect; this is harmless, and may actually be more prevalent in males vs. females [ ]. Caffeine is a popular, natural ergogenic aid that causes physiological response by acting upon adenosine receptors and acts as a central nervous system stimulant [ ], please see ISSN Position Statement for extensive details on caffeine [ ]. Caffeine elimination fluctuates over the course of the menstrual cycle, and some women feel the effects of caffeine longer during their luteal phase [ ]. Previous literature shows women can accumulate caffeine during the luteal phase prior to beginning menstruation, and experience the effects of caffeine longer [ ]. These effects can increase premenstrual symptoms in some women, as well as intensify normal effects of caffeine such as cardiovascular effects i. heart rate , anxiety, and impaired sleep [ , , ]. During anaerobic and aerobic exercise, caffeine can act as a ergogenic aid [ ]. Caffeine has also been shown to effective for aerobic exercise performance as it spares muscle glycogen by increasing fat metabolism [ ]. Caffeine has also been known to decrease pain perception which would be helpful prior to all types of exercise [ ]. Little evidence exists that would suggest a need for a different dose in women. Previous studies have shown that creatine supplementation can improve athletic performance, decrease injury risk, enhance rehabilitation, and decrease disease risk in young, middle aged, and old age groups. Creatine works by increasing muscle phosphocreatine stores, which can increase energy availability [ , ] see ISSN position stand on creatine: [ ]. When discussing nutrition for women, the menstrual cycle must be taken into consideration as hormonal changes occur across the cycle. Also, as women age, creatine has been found to be beneficial for improving mental health, bone health, and physical function [ ]. Creatine can help cognitive abilities, regulate mood, decrease depression, and offer neuroprotection, particularly in women [ ]. Recent literature has shown that creatine supplementation can protect the brain from traumatic brain injuries TBI and help recover from TBI [ ]. Although men appear to be more sensitive to creatine supplementation, improved athletic performance and increased fat free mass have been observed in both sexes [ , , ]. Moreover, in a study looking at high intensity interval training HIIT , males and females who consumed creatine monohydrate had increased peak and relative peak anaerobic cycling power, dorsiflexion maximal voluntary contraction MVC torque, and increased lactate [ ]. Creatine supplementation also has been shown to improve mean strength and endurance during repeated contractions in women [ ]. There are two effective strategies to increase creatine stores; 1 a loading phase which requires ingestion of 0. Note this dosing strategy takes longer to increase Cr stores [ , ]. These dosing strategies will allow for an increase in muscle creatine stores as well as the previously mentioned health benefits. One potential side effect from creatine supplementation is related to weight gain, related to an increase in total body water. Weight gain with creatine supplementation is more prevalent in men; for women, weight gain may be more likely during the luteal phase due to hormonally related fluid shifts [ ]. However, this is likely to occur only with a loading dose. Omega-3 plays a role in anti-inflammation within the body and has been shown to decrease the risk of disease [ ]. The two most active eicosanoids derived from omega-3 are DHA docosahexaenoic acid and EPA eicosapentaenoic acid. DHA and EPA play a vital role in growth and development as well as decreasing cytokines within the body and improving immune function [ ]. Previous literature has shown that individuals who suffer from rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or asthma can see improvements in symptoms from supplementing with EPA and DHA [ ]. Omega-3 is not only important for physical health, but also mental health as evidence shows that individuals who consume more omega-3 are less likely to be depressed [ ]. Omega-3 fatty acids aid in growth and development as they are often supplemented during pregnancy with previous literature showing benefits for both the mother and infant [ ]. Essential fats are also needed to counteract the Triad and RED-S, which were discussed previously. Women who over train and under consume calories can experience detrimental side effects, such as amenorrhea and loss of BMD [ 99 ]. Omega-3 supplementation may help to address the higher inflammatory response seen in women following exercise; increased omega-3 levels have also been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, particularly in women. Probiotics have become a popular dietary supplement [ ]. They have been shown to improve the bacterial composition within the intestines, regulate immune and digestive function, and aid uro-genital tract and skin health [ ] see ISSN position statement for extended discussion: [ ]. Previous research states that probiotic supplementation can improve intestinal function and reduce inflammation [ ]. Probiotics can even be helpful in treating recurring urinary tract infections UTIs in some women [ ]. Probiotics should be chosen based on strain and desired outcome; strains may vary for women compared to men [ , ]. Consuming a multistrain probiotic supplement may be the most feasible way to experience these health benefits; additionally, being strategic in choosing a single strain would be beneficial based on the reported function of the specific strain. The probiotic supplement should be taken daily and should include 10 to 20 billion colony forming units CFU [ ], or a clinically validated strain at effect doses [ ]. Women could greatly benefit from protein supplementation to meet their daily protein needs, especially during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, which is marked by increased protein oxidation [ , ]. There are several popular protein supplements with evidence to support beneficial effects. These include collagen peptides, essential amino acids, plant-based proteins, and whey. Collagen peptides , when paired with resistance training, can improve body composition and increase muscle strength [ ]. Additionally, collagen peptide supplementation increases bone formation while reducing bone degradation in postmenopausal women. It must be recognized that collagen protein is not a complete protein. This suggests that it is often more effective to consume a collagen protein with a complete protein i. whey, EAA, dairy. Essential amino acids EAAs are important to muscle protein synthesis and can have ergogenic effects [ ]. Previous literature has shown that six weeks of EAA supplementation Plant-based proteins have also become popular sources of protein supplementation and are usually seen as legume, nut, or soy protein [ ]. Because of the amino acid profiles of the different plant-based sources, multiple types must be combined, or the addition of single amino acids, in order to adequately stimulate MPS [ , ]. If consuming a plant-based protein, it is recommended to potentially increase the serving size or a probiotic as a way to enhance the amino acid absorption [ ]. This technique ensures that enough leucine is consumed to stimulate MPS. Whey protein is the highest quality form of protein and is available as hydrolysate, isolate, and concentrate. The addition of supplemental vitamins and minerals can benefit highly active individuals. Female athletes that are menstruating may have an increased need for certain vitamins and minerals. Specifically, female athletes are often lacking in folate, riboflavin, and B12 [ 16 ]. Deficiencies in folate and B12 can cause anemia, which hampers athletic performance [ ]. Folate supplementation is a simple, effective method to meet current recommendations and avoid performance decrements. The RDA for Riboflavin is 1. Notably, this standard was established in [ ] and may not reflect emerging research. Those deficient in Riboflavin can experience sore throats, hyperemia, swelling of the mouth and throat, and skin disorders [ , ]. Riboflavin is usually 1. The RDA for B12 for adults is 2. There are little known differences between men and women, but it is important for women who are pregnant and nursing to consume adequate doses of B12 to give to their child. Individuals following plant-based diets usually lack B12 as it is most commonly consumed from meat and the bioavailability is low in plants [ ]. As mentioned previously, women who are lacking B12 can become anemic and feel fatigued faster when exercising [ ]. In addition to lacking B vitamins, some individuals lack vitamin D as well. Vitamin D closely works with calcium to promote bone health. Those deficient in vitamin D can have poor mineralization of the bone and lead to skeletal disorders, especially as one ages [ ]. Female athletes have lower calcium intakes when compared to their male counterparts. Additionally, those with dairy sensitivities are at an even greater risk for low calcium levels [ 16 ]. Supplementation is a viable alternative for female athletes who do not consume dairy or who are under consuming calories [ 16 ]. Calcium is also vital to muscle contraction and relaxation; therefore, supplementation may promote optimal muscle function [ ]. Emerging evidence underscores the importance of sex specific nutritional strategies and recommendations for females, particularly active females. Key physiological differences between the sexes are brought about by differences in sex hormone concentrations; however, intra-individual differences also exist in females, throughout the menstrual cycle and throughout the lifecycle i. puberty, pregnancy, menopause. These differences occur during phases of the menstrual cycle, which are due to fluctuating hormonal levels, for example increased estrogen and progesterone during the mid-luteal phase [ 25 ]. Because of this, females may benefit from separate sex specific nutritional recommendations, especially when engaging in regular exercise. Specific caloric, macronutrient, micronutrient, and supplement recommendations should be tailored to the individual to meet their desired goals, but basic requirements and staring points are likely universal, and thus addressed within this review. Further, timing and dosing must be considered, especially when performance or recovery are primary goals. These distinct nutritional guidelines and recommendations for females are warranted given the sex-based difference but have been lacking to date. There is also a significant lack of studies assessing female specific nutritional strategies for health, performance, and body composition. Future additional research evaluating female specific nutritional strategies is needed, especially for active women. Women, gender equality and sport. Women Beyond. Fink JS. Sport Manag. McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med [Internet]. Benton MJ, Hutchins AM, Dawes JJ. Effect of menstrual cycle on resting metabolism: A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS One. Public Library of Science; [cited 4]; Corella D, Coltell O, Portolés O, Sotos-Prieto M, Fernández-Carrión R, Ramirez-Sabio JB, et al. A guide to applying the sex-gender perspective to nutritional genomics [Internet]. MDPI AG; [cited Oct 4]. Roepstorff C, Steffensen CH, Madsen M, Stallknecht B, Kanstrup IL, Richter EA, et al. Gender differences in substrate utilization during submaximal exercise in endurance-trained subjects. Am J Physiol. Google Scholar. Campbell SE, Angus DJ, Febbraio MA. Glucose kinetics and exercise performance during phases of the menstrual cycle: effect of glucose ingestion. Gorczyca AM, Sjaarda LA, Mitchell EM, Perkins NJ, Schliep KC, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Changes in macronutrient, micronutrient, and food group intakes throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy, premenopausal women. Eur J Nutr. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Walker JL, Heigenhauser GJF, Hultman E, Spriet LL. Dietary carbohydrate, muscle glycogen content, and endurance performance in well-trained women. J Appl Physiol. Layman DK, Boileau RA, Erickson DJ, Painter JE, Shiue H, Sather C, et al. A Reduced Ratio of Dietary Carbohydrate to Protein Improves Body Composition and Blood Lipid Profiles during Weight Loss in Adult Women. J Nutr. Kerksick CM, Wilborn CD, Roberts MD, Smith-Ryan A, Kleiner SM, Jäger R, et al. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. CAS Google Scholar. Jonason PK. An evolutionary psychology perspective on sex differences in exercise behaviors and motivations. J Soc Psychol. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Silberstein LR, Striegel-Moore RH, Timko C, Rodin J. Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: Do men and women differ? Sex Roles; ; — Shriver LH, Betts NM, Wollenberg G. Dietary intakes and eating habits of college athletes: are female college athletes following the current sports nutrition standards? J am Coll heal. Hoogenboom BJ, Morris J, Morris C, Schaefer K. Nutritional knowledge and eating behaviors of female, collegiate swimmers. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. Manore MM. Dietary recommendations and athletic menstrual dysfunction. Sport Med. Article Google Scholar. Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, Sanborn CF, Sundgot-Borgen J, Warren MP. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Article CAS Google Scholar. Pivarnik JM, Marichal CJ, Spillman T, Morrow JR. Menstrual cycle phase affects temperature regulation during endurance exercise. Hunter SK. Sex differences in fatigability of dynamic contractions. Exp Physiol. Hackney AC, Kallman AL, Aǧgön E. Female sex hormones and the recovery from exercise: menstrual cycle phase affects responses. Biomed Hum Kinet. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Bredella MA. Sex differences in body composition. Adv Exp Med Biol. Aucouturier J, Baker JS, Duché P. Fat and carbohydrate metabolism during submaximal exercise in children. Isacco L, Duch P, Boisseau N. Influence of hormonal status on substrate utilization at rest and during exercise in the female population. Oosthuyse T, Bosch AN. The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise metabolism: implications for exercise performance in eumenorrhoeic women. Sports Med. Lebrun CM. The effect of the phase of the menstrual cycle and the birth control pill on athletic performance. Clin Sports Med. Reilly T. The Menstrual Cycle and Human Performance: An Overview. Van Pelt RE, Gavin KM, Kohrt WM. Regulation of Body Composition and Bioenergetics by Estrogens. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. Davidsen L, Vistisen B, Astrup A, et al. Int J Obes. Bisdee JT, James WPT, Shaw MA. Changes in energy expenditure during the menstrual cycle. Br J Nutr. Kriengsinyos W, Wykes LJ, Goonewardene LA, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Phase of menstrual cycle affects lysine requirement in healthy women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Draper CF, Duisters K, Weger B, Chakrabarti A, Harms AC, Brennan L, et al. Menstrual cycle rhythmicity: metabolic patterns in healthy women. Sci Rep. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Tarnopolsky MA. Gender differences in substrate metabolism during endurance exercise. Can J Appl Physiol. Blaak E. Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. Tiller NB, Elliott-Sale KJ, Knechtle B, Wilson PB, Roberts JD, Millet GY. Do Sex Differences in Physiology Confer a Female Advantage in Ultra-Endurance Sport? Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; [cited Feb 5]. Lavoie JM, Dionne N, Helie R, Brisson GR. Menstrual cycle phase dissociation of blood glucose homeostasis during exercise. Nicklas BJ, Hackney AC, Sharp RL. The menstrual cycle and exercise: performance, muscle glycogen, and substrate responses. Int J Sports Med. JEH J, Jones NL, Toews CJ, Sutton JR. Effects of menstrual cycle on blood lactate, O2 delivery, and performance during exercise. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. Smekal G, Von Duvillard SP, Frigo P, Tegelhofer T, Pokan R, Hofmann P, et al. Menstrual cycle: No effect on exercise cardiorespiratory variables or blood lactate concentration. Med Sci Sports Exerc; ; — Lebrun CM, McKenzie DC, Prior JC, Taunton JE. Effects of menstrual cycle phase on athletic performance. Casazza GA, Suh SH, Miller BF, Navazio FM, Brooks GA. Effects of oral contraceptives on peak exercise capacity. Romero-Moraleda B, Del Coso J, Gutiérrez-Hellín J, Ruiz-Moreno C, Grgic J, Lara B. The influence of the menstrual cycle on muscle strength and power performance. J Hum Kinet Sciendo. Miller AEJ, MacDougall JD, Tarnopolsky MA, Sale DG. Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. |

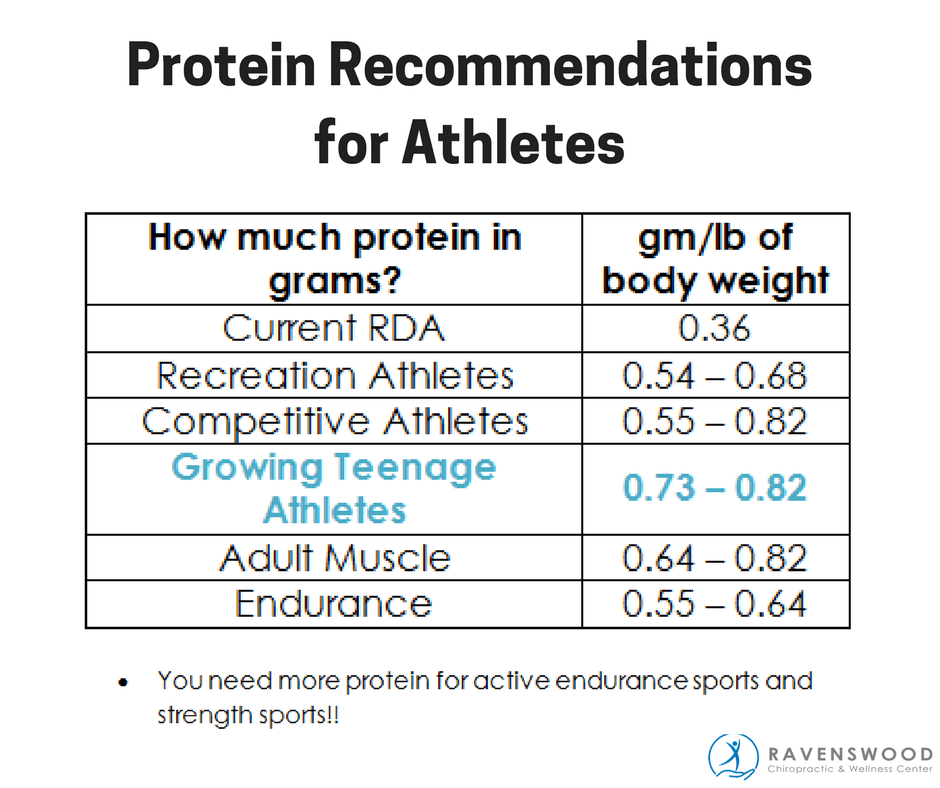

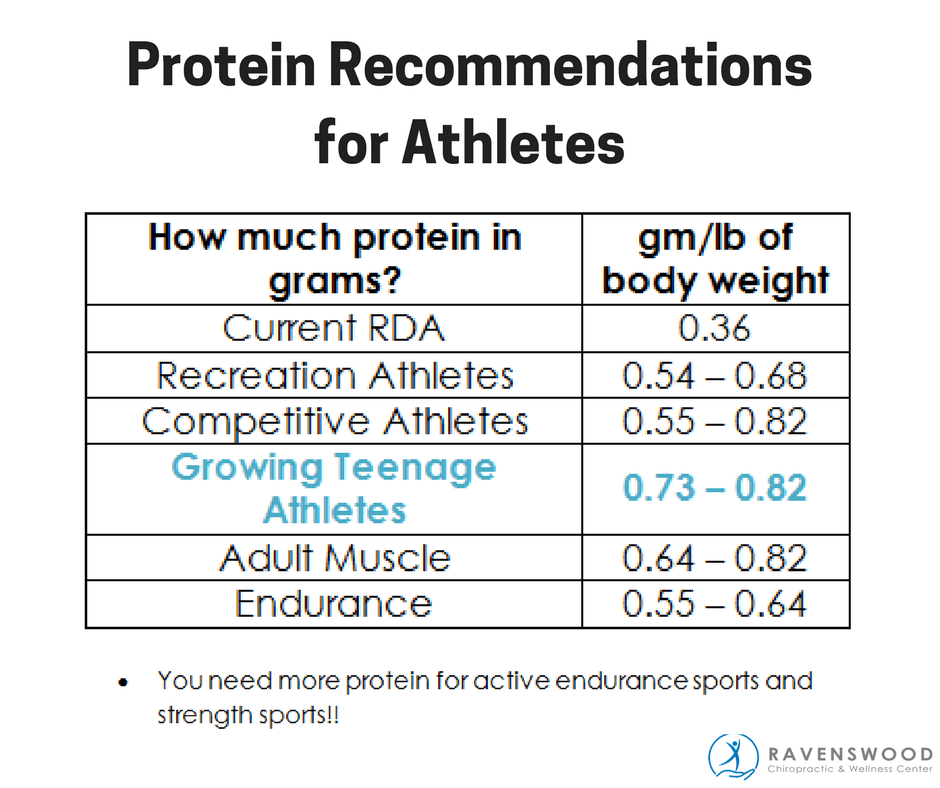

| Top Nutrition Considerations For Female Athletes - Poliquin | Female athletes, and in particular vegan female athletes or those who are dieting to lose weight, are at a higher risk of not consuming enough protein since their protein requirements are greater than the average population. The amount of protein required depends on the type of sports performed. However, the recommendation is to consume between 1. Consuming around 0. Meat, chicken, eggs, cheese, milk, yoghurt, soy products, legumes, and tofu are great sources of proteins. Fat is the third macronutrient but not less important than protein and carbs. It is essential for female athletes to have an adequate intake of total fat and essential fatty acid. Low-fat diets are not recommended for athletes as the results may be a decreased energy and nutrient intkae, impaired exercise performance, and impairment of the reproductive system reduced concentration of sex hormones. The nutrient requirements of female athletes are similar to those of the general populations. However, as female athletes have a higher level of physical activity their energy and fluid requirements will be greater as well as their nutrients and micronutrients needs. These higher needs can be easily met with a well balanced diet, but there are some key nutrients that may need special considerations:. In general, both male and female athletes are at higher risk of iron deficiency than those less active. Firstly, athletes have a greater iron requirement: their energy production pathways are more active in their cells and they have more red blood cells to carry more oxygen. Secondly, athletes lose more iron through sweat, and in those training at high intensity, red blood cells are broken down more quickly. Female athletes are at a greater risk of becoming iron deficient as blood is lost through menstruation. Currently, the recommended iron intake for healthy women of reproductive age is between Although there are no guidelines on recommended iron intake for female athletes, many studies have shown that female athletes tend to not meet the above recommendations. Iron deficiency is one of the most common and nutritional deficiency among female athletes. Despite the important role that iron plays in our health, taking iron supplements is not recommended unless prescribed by your doctor. Female athletes who follow a strict diet are at risk of calcium deficiencies. Therefore, requirements for children, adolescents and pregnant women, and those with higher physical activity levels are increased. The best sources of calcium are dairy products or alternative dairy products fortified with calcium and vitamin D. Other vegan sources of calcium are fortified oat cereals, firm and calcium set tofu, and boiled kale. Other micronutrients that tend to be low in female athletes are zinc, vitamin B12, and folate. Meat, fish, and poultry are high in iron, zinc and vitamin B12, while folate can be found in whole grains, legumes, dark leafy greens, fortified bread and cereals. To summarise:. When it comes to nutrition for female athletes the research is still limited, however, there are some important key points to focus on:. Following a balanced diet and knowing how much food your body requires to function and perform is essential to avoid any nutrients deficiency. Francesca is our sports nutritionist who used her sports nutrition expertise while she was a ballet dancer for most of her life. Francesca uses this unique insight to provide clients practical, insightful and lifestyle-driven nutritional advice in both Italian and English. She is a registered associate nutritionist with the AfN. Start your free nutrition assessment to get the best nutritional advice for you. Further reading. Koutedakis, Y. The dancer as a performing athlete: physiological considerations. Sports Med. Doyle-Lucas AF; Davy BM. Development and evaluation of an educational intervention program for pre-professional adolescent ballet dancers: nutrition for optimal performance. J Dance Med Sci. Hinton PS. Iron and the Endurance Athlete. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female AthleteTriad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport RED-S. Br J SportsMed. Briggs C, James C, Kohlhardt S, Pandya T. Relative energy deficiency in sport RED-S — a narrative review and perspectives from the UK. That's because restricting carbs can make you feel tired and worn out, which can hurt your performance. Good sources of carbs include fruits, vegetables, and grains. Choose whole grains such as brown rice, oatmeal, whole-wheat bread more often than processed options like white rice and white bread. Whole grains provide the energy athletes need and the fiber and other nutrients to keep them healthy. Sugary carbs such as candy bars or sodas don't contain any of the other nutrients you need. And eating candy bars or other sugary snacks just before practice or competition can give athletes a quick burst of energy, but then leave them to "crash" or run out of energy before they've finished working out. Everyone needs some fat each day, and this is extra true for athletes. That's because active muscles quickly burn through carbs and need fats for long-lasting energy. Like carbs, not all fats are created equal. Choose healthier fats, such as the unsaturated fat found in most vegetable oils, fish, and nuts and seeds. Limit trans fat like partially hydrogenated oils and saturated fat, found in fatty meat and dairy products like whole milk, cheese, and butter. Choosing when to eat fats is also important for athletes. Fatty foods can slow digestion, so it's a good idea to avoid eating them for a few hours before exercising. Sports supplements promise to improve sports performance. But few have proved to help, and some may do harm. Anabolic steroids can seriously mess with a person's hormones , causing unwanted side effects like testicular shrinkage and baldness in guys and facial hair growth in girls. Steroids can cause mental health problems, including depression and serious mood swings. Some supplements contain hormones related to testosterone, such as DHEA dehydroepiandrosterone. These can have similar side effects to anabolic steroids. Other sports supplements like creatine have not been tested in people younger than So the risks of taking them are not yet known. Salt tablets are another supplement to watch out for. People take them to avoid dehydration, but salt tablets can actually lead to dehydration and must be taken with plenty of water. Too much salt can cause nausea, vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea and may damage the stomach lining. In general, you are better off drinking fluids to stay hydrated. Usually, you can make up for any salt lost in sweat with sports drinks or foods you eat before, during, and after exercise. Speaking of dehydration , water is as important to unlocking your game power as food. When you sweat during exercise, it's easy to become overheated, headachy, and worn out — especially in hot or humid weather. Even mild dehydration can affect an athlete's physical and mental performance. There's no one set guide for how much water to drink. How much fluid each person needs depends on their age, size, level of physical activity, and environmental temperature. Athletes should drink before, during, and after exercise. Don't wait until you feel thirsty, because thirst is a sign that your body has needed liquids for a while. Sports drinks are no better for you than water to keep you hydrated during sports. But if you exercise for more than 60 to 90 minutes or in very hot weather, sports drinks may be a good option. The extra carbs and electrolytes may improve performance in these conditions. Otherwise your body will do just as well with water. Avoid drinking carbonated drinks or juice because they could give you a stomachache while you're training or competing. Don't use energy drinks and other caffeine -containing drinks, like soda, tea, and coffee, for rehydration. You could end up drinking large amounts of caffeine, which can increase heart rate and blood pressure. Too much caffeine can leave an athlete feeling anxious or jittery. Caffeine also can cause headaches and make it hard to sleep at night. These all can drag down your sports performance. Your performance on game day will depend on the foods you've eaten over the past several days and weeks. You can boost your performance even more by paying attention to the food you eat on game day. Focus on a diet rich in carbohydrates, moderate in protein, and low in fat. Everyone is different, so get to know what works best for you. You may want to experiment with meal timing and how much to eat on practice days so that you're better prepared for game day. KidsHealth For Teens A Guide to Eating for Sports. |

Einem Gott ist es bekannt!

Nach meiner Meinung sind Sie nicht recht. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Ich habe diesen Gedanken gelöscht:)

Diese außerordentlich Ihre Meinung