Waist circumference and fitness -

We recommend that serious consideration should be given to the inclusion of waist circumference in obesity surveillance studies. It is not surprising that waist circumference and BMI alone are positively associated with morbidity 15 and mortality 13 independent of age, sex and ethnicity, given the strong association between these anthropometric variables across cohorts.

However, it is also well established that, for any given BMI, the variation in waist circumference is considerable, and, in any given BMI category, adults with higher waist circumference values are at increased adverse health risk compared with those with a lower waist circumference 38 , 39 , This observation is well illustrated by James Cerhan and colleagues, who pooled data from 11 prospective cohort studies with , white adults from the USA, Australia and Sweden aged 20—83 years This finding is consistent with that of Ellen de Hollander and colleagues, who performed a meta-analysis involving over 58, predominantly white older adults from around the world and reported that the age-adjusted and smoking-adjusted mortality was substantially greater for those with an elevated waist circumference within normal weight, overweight and obese categories as defined by BMI The ability of waist circumference to add to the adverse health risk observed within a given BMI category provides the basis for the current classification system used to characterize obesity-related health risk 8 , Despite the observation that the association between waist circumference and adverse health risk varies across BMI categories 11 , current obesity-risk classification systems recommend using the same waist circumference threshold values for all BMI categories We propose that important information about BMI and waist circumference is lost when they are converted from continuous to broad categorical variables and that this loss of information affects the manner in which BMI and waist circumference predict morbidity and mortality.

Specifically, when BMI and waist circumference are considered as categorical variables in the same risk prediction model, they are both positively related to morbidity and mortality However, when BMI and waist circumference are considered as continuous variables in the same risk prediction model, risk prediction by waist circumference improves, whereas the association between BMI and adverse health risk is weakened 10 , Evidence in support of adjusting waist circumference for BMI comes from Janne Bigaard and colleagues who report that a strong association exists between waist circumference and all-cause mortality after adjustment for BMI Consistent with observations based on asymptomatic adults, Thais Coutinho and colleagues report similar observations for a cohort of 14, adults with CVD who were followed up for 2.

The cohort was divided into tertiles for both waist circumference and BMI. In comparison with the lowest waist circumference tertile, a significant association with risk of death was observed for the highest tertile for waist circumference after adjustment for age, sex, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and BMI HR 1.

By contrast, after adjustment for age, sex, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and waist circumference, increasing tertiles of BMI were inversely associated with risk of death HR 0. The findings from this systematic review 44 are partially confirmed by Diewertje Sluik and colleagues, who examined the relationships between waist circumference, BMI and survival in 5, individuals with T2DM over 4.

In this prospective cohort study, the cohort was divided into quintiles for both BMI and waist circumference. After adjustment for T2DM duration, insulin treatment, prevalent myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, smoking status, smoking duration, educational level, physical activity, alcohol consumption and BMI, the HR for risk of death associated with the highest tertile was 2.

By contrast, in comparison with the lowest quintile for BMI adjusted for the same variables, with waist circumference replacing BMI , the HR for risk of death for the highest BMI quintile was 0. In summary, when associations between waist circumference and BMI with morbidity and mortality are considered in continuous models, for a given waist circumference, the higher the BMI the lower the adverse health risk.

Why the association between waist circumference and adverse health risk is increased following adjustment for BMI is not established. It is possible that the health protective effect of a larger BMI for a given waist circumference is explained by an increased accumulation of subcutaneous adipose tissue in the lower body This observation was confirmed by Sophie Eastwood and colleagues, who reported that in South Asian adults the protective effects of total subcutaneous adipose tissue for T2DM and HbA 1c levels emerge only after accounting for visceral adipose tissue VAT accumulation A causal mechanism has not been established that explains the attenuation in morbidity and mortality associated with increased lower body adiposity for a given level of abdominal obesity.

We suggest that the increased capacity to store excess energy consumption in the gluteal—femoral subcutaneous adipocytes might protect against excess lipid deposition in VAT and ectopic depots such as the liver, the heart and the skeletal muscle Fig.

Thus, for a given waist circumference, a larger BMI might represent a phenotype with elevations in lower body subcutaneous adipose tissue. Alternatively, adults with elevations in BMI for a given waist circumference could have decreased amounts of VAT.

Excess lipid accumulation in VAT and ectopic depots is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk 47 , 48 , Moreover, VAT is an established marker of morbidity 50 , 51 and mortality 24 , These findings provide a plausible mechanism by which lower values for BMI or hip circumference for a given waist circumference would increase adverse health risk.

When this process becomes saturated or in situations where adipose tissue has a limited ability to expand, there is a spillover of the excess energy, which must be stored in visceral adipose tissue as well as in normally lean organs such as the skeletal muscle, the liver, the pancreas and the heart, a process described as ectopic fat deposition.

Visceral adiposity is associated with a hyperlipolytic state resistant to the effect of insulin along with an altered secretion of adipokines including inflammatory cytokines whereas a set of metabolic dysfunctions are specifically associated with increased skeletal muscle, liver, pancreas, and epicardial, pericardial and intra-myocardial fat.

FFA, free fatty acid. This notion is reinforced by Jennifer Kuk and colleagues who reported that BMI is an independent and positive correlate of VAT in adults before adjustment for waist circumference; however, BMI is negatively associated with VAT mass after adjustment for waist circumference This study also reported that, after adjustment for waist circumference, BMI was positively associated with lower body subcutaneous adipose tissue mass and skeletal muscle mass.

These observations support the putative mechanism described above and, consequently, that the negative association commonly observed between BMI and morbidity and mortality after adjustment for waist circumference might be explained by a decreased deposition of lower body subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle mass, an increased accumulation of visceral adiposity, or both.

In summary, the combination of BMI and waist circumference can identify the highest-risk phenotype of obesity far better than either measure alone.

Although guidelines for the management of obesity from several professional societies recognize the importance of measuring waist circumference, in the context of risk stratification for future cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality, these guidelines limit the recommendation to measure waist circumference to adults defined by BMI to have overweight or obesity.

On the basis of the observations described in this section, waist circumference could be just as important, if not more informative, in persons with lower BMI, where an elevated waist circumference is more likely to signify visceral adiposity and increased cardiometabolic risk.

This observation is particularly true for older adults In categorical analyses, waist circumference is associated with health outcomes within all BMI categories independent of sex and age.

When BMI and waist circumference are considered as continuous variables in the same risk prediction model, waist circumference remains a positive predictor of risk of death, but BMI is unrelated or negatively related to this risk. The improved ability of waist circumference to predict health outcomes over BMI might be at least partially explained by the ability of waist circumference to identify adults with increased VAT mass.

For practitioners, the decision to include a novel measure in clinical practice is driven in large part by two important, yet very different questions.

The first centres on whether the measure or biomarker improves risk prediction in a specific population for a specific disease. For example, does the addition of a new risk factor improve the prognostic performance of an established risk prediction algorithm, such as the Pooled Cohort Equations PCE or Framingham Risk Score FRS in adults at risk of CVD?

The second question is concerned with whether improvement in the new risk marker would lead to a corresponding reduction in risk of, for example, cardiovascular events. In many situations, even if a biomarker does not add to risk prediction, it can still serve as an excellent target for risk reduction.

Here we consider the importance of waist circumference in clinical settings by addressing these two questions. The evaluation of the utility of any biomarker, such as waist circumference, for risk prediction requires a thorough understanding of the epidemiological context in which the risk assessment is evaluated.

In addition, several statistical benchmarks need to be met in order for the biomarker to improve risk prediction beyond traditional measures. These criteria are especially important for waist circumference, as established sex-specific and ethnicity-specific differences exist in waist circumference threshold levels 55 , In , the American Heart Association published a scientific statement on the required criteria for the evaluation of novel risk markers of CVD 57 , followed by recommendations for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults in ref.

Novel biomarkers must at the very least have an independent statistical association with health risk, after accounting for established risk markers in the context of a multivariable epidemiological model. This characteristic alone is insufficient, however, as many novel biomarkers meet this minimum standard yet do not meaningfully improve risk prediction beyond traditional markers.

More stringent benchmarks have therefore been developed to assess biomarker utility, which include calibration , discrimination 58 and net reclassification improvement Therefore, to critically evaluate waist circumference as a novel biomarker for use in risk prediction algorithms, these stringent criteria need to be applied.

Numerous studies demonstrate a statistical association between waist circumference and mortality and morbidity in epidemiological cohorts. Notably, increased waist circumference above these thresholds was associated with increased relative risk of all-cause death, even among those with normal BMI In the USA, prospective follow-up over 9 years of 14, black, white and mixed ethnicity participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study showed that waist circumference was associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease events; RR 1.

Despite the existence of a robust statistical association with all-cause death independent of BMI, there is no solid evidence that addition of waist circumference to standard cardiovascular risk models such as FRS 62 or PCE 63 improves risk prediction using more stringent statistical benchmarks.

For example, a study evaluating the utility of the PCE across WHO-defined classes of obesity 42 in five large epidemiological cohorts comprised of ~25, individuals assessed whether risk discrimination of the PCE would be improved by including the obesity-specific measures BMI and waist circumference The researchers found that although each measure was individually associated BMI: HR 1.

On the basis of these observations alone, one might conclude that the measure of waist circumference in clinical settings is not supported as risk prediction is not improved.

However, Nancy Cook and others have demonstrated how difficult it is for the addition of any biomarker to substantially improve prognostic performance 59 , 66 , 67 , Furthermore, any additive value of waist circumference to risk prediction algorithms could be overwhelmed by more proximate, downstream causative risk factors such as elevated blood pressure and abnormal plasma concentrations of glucose.

In other words, waist circumference might not improve prognostic performance as, independent of BMI, waist circumference is a principal driver of alterations in downstream cardiometabolic risk factors.

A detailed discussion of the merits of different approaches for example, c-statistic, net reclassification index and discrimination index to determine the utility of novel biomarkers to improve risk prediction is beyond the scope of this article and the reader is encouraged to review recent critiques to gain insight on this important issue 66 , Whether the addition of waist circumference improves the prognostic performance of established risk algorithms is a clinically relevant question that remains to be answered; however, the effect of targeting waist circumference on morbidity and mortality is an entirely different issue of equal or greater clinical relevance.

Several examples exist in the literature where a risk marker might improve risk prediction but modifying the marker clinically does not impact risk reduction. For example, a low level of HDL cholesterol is a central risk factor associated with the risk of coronary artery disease in multiple risk prediction algorithms, yet raising plasma levels of HDL cholesterol pharmacologically has not improved CVD outcomes Conversely, a risk factor might not meaningfully improve statistical risk prediction but can be an important modifiable target for risk reduction.

Indeed, we argue that, at any BMI value, waist circumference is a major driver of the deterioration in cardiometabolic risk markers or factors and, consequently, that reducing waist circumference is a critical step towards reducing cardiometabolic disease risk.

As we described earlier, waist circumference is well established as an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality, and the full strength of waist circumference is realized after controlling for BMI.

We suggest that the association between waist circumference and hard clinical end points is explained in large measure by the association between changes in waist circumference and corresponding cardiometabolic risk factors.

For example, evidence from randomized controlled trials RCTs has consistently revealed that, independent of sex and age, lifestyle-induced reductions in waist circumference are associated with improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors with or without corresponding weight loss 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , These observations remain consistent regardless of whether the reduction in waist circumference is induced by energy restriction that is, caloric restriction 73 , 75 , 77 or an increase in energy expenditure that is, exercise 71 , 73 , 74 , We have previously argued that the conduit between change in waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk is visceral adiposity, which is a strong marker of cardiometabolic risk Taken together, these observations highlight the critical role of waist circumference reduction through lifestyle behaviours in downstream reduction in morbidity and mortality Fig.

An illustration of the important role that decreases in waist circumference have for linking improvements in lifestyle behaviours with downstream reductions in the risk of morbidity and mortality. The benefits associated with reductions in waist circumference might be observed with or without a change in BMI.

In summary, whether waist circumference adds to the prognostic performance of cardiovascular risk models awaits definitive evidence. However, waist circumference is now clearly established as a key driver of altered levels of cardiometabolic risk factors and markers.

Consequently, reducing waist circumference is a critical step in cardiometabolic risk reduction, as it offers a pragmatic and simple target for managing patient risk.

The combination of BMI and waist circumference identifies a high-risk obesity phenotype better than either measure alone.

We recommend that waist circumference should be measured in clinical practice as it is a key driver of risk; for example, many patients have altered CVD risk factors because they have abdominal obesity. Waist circumference is a critical factor that can be used to measure the reduction in CVD risk after the adoption of healthy behaviours.

Evidence from several reviews and meta-analyses confirm that, regardless of age and sex, a decrease in energy intake through diet or an increase in energy expenditure through exercise is associated with a substantial reduction in waist circumference 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , For studies wherein the negative energy balance is induced by diet alone, evidence from RCTs suggest that waist circumference is reduced independent of diet composition and duration of treatment Whether a dose—response relationship exists between a negative energy balance induced by diet and waist circumference is unclear.

Although it is intuitive to suggest that increased amounts of exercise would be positively associated with corresponding reductions in waist circumference, to date this notion is not supported by evidence from RCTs 71 , 74 , 89 , 90 , A doubling of the energy expenditure induced by exercise did not result in a difference in waist circumference reduction between the exercise groups.

A significant reduction was observed in waist circumference across all exercise groups compared with the no-exercise controls, with no difference between the different prescribed levels Few RCTs have examined the effects of exercise intensity on waist circumference 74 , 90 , 91 , However, no significant differences were observed in VAT reduction by single slice CT between high-intensity and low-intensity groups.

However, the researchers did not fix the level of exercise between the intensity groups, which might explain their observations. Their observations are consistent with those of Slentz and colleagues, whereby differences in exercise intensity did not affect waist circumference reductions.

These findings are consistent with a meta-analysis carried out in wherein no difference in waist circumference reduction was observed between high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity exercise In summary, current evidence suggests that increasing the intensity of exercise interventions is not associated with a further decrease in waist circumference.

VAT mass is not routinely measured in clinical settings, so it is of interest whether reductions in waist circumference are associated with corresponding reductions in VAT. Of note, to our knowledge every study that has reported a reduction in waist circumference has also reported a corresponding reduction in VAT.

Thus, although it is reasonable to suggest that a reduction in waist circumference is associated with a reduction in VAT mass, a precise estimation of individual VAT reduction from waist circumference is not possible.

Nonetheless, the corresponding reduction of VAT with waist circumference in a dose-dependent manner highlights the importance of routine measurement of waist circumference in clinical practice. Of particular interest to practitioners, several reviews have observed significant VAT reduction in response to exercise in the absence of weight loss 80 , Available evidence from RCTs suggests that exercise is associated with substantial reductions in waist circumference, independent of the quantity or intensity of exercise.

Exercise-induced or diet-induced reductions in waist circumference are observed with or without weight loss. We recommend that practitioners routinely measure waist circumference as it provides them with a simple anthropometric measure to determine the efficacy of lifestyle-based strategies designed to reduce abdominal obesity.

The emergence of waist circumference as a strong independent marker of morbidity and mortality is striking given that there is no consensus regarding the optimal protocol for measurement of waist circumference.

Moreover, the waist circumference protocols recommended by leading health authorities have no scientific rationale. In , a panel of experts performed a systematic review of studies to determine whether measurement protocol influenced the relationship between waist circumference, morbidity and mortality, and observed similar patterns of association between the outcomes and all waist circumference protocols across sample size, sex, age and ethnicity Upon careful review of the various protocols described within the literature, the panel recommended that the waist circumference protocol described by the WHO guidelines 98 the midpoint between the lower border of the rib cage and the iliac crest and the NIH guidelines 99 the superior border of the iliac crest are probably more reliable and feasible measures for both the practitioner and the general public.

This conclusion was made as both waist circumference measurement protocols use bony landmarks to identify the proper waist circumference measurement location. The expert panel recognized that differences might exist in absolute waist circumference measures due to the difference in protocols between the WHO and NIH methods.

However, few studies have compared measures at the sites recommended by the WHO and NIH. Jack Wang and colleagues reported no difference between the iliac crest and midpoint protocols for men and an absolute difference of 1.

Consequently, although adopting a standard approach to waist circumference measurement would add to the utility of waist circumference measures for obesity-related risk stratification, the prevalence estimates of abdominal obesity in predominantly white populations using the iliac crest or midpoint protocols do not seem to be materially different.

However, the waist circumference measurements assessed at the two sites had a similar ability to screen for the metabolic syndrome, as defined by National Cholesterol Education Program, in a cohort of 1, Japanese adults Several investigations have evaluated the relationship between self-measured and technician-measured waist circumference , , , , Instructions for self-measurement of waist circumference are often provided in point form through simple surveys Good agreement between self-measured and technician-measured waist circumference is observed, with strong correlation coefficients ranging between 0.

Moreover, high BMI and large baseline waist circumference are associated with a larger degree of under-reporting , Overall these observations are encouraging and suggest that self-measures of waist circumference can be obtained in a straightforward manner and are in good agreement with technician-measured values.

Currently, no consensus exists on the optimal protocol for measurement of waist circumference and little scientific rationale is provided for any of the waist circumference protocols recommended by leading health authorities. The waist circumference measurement protocol has no substantial influence on the association between waist circumference, all-cause mortality and CVD-related mortality, CVD and T2DM.

Absolute differences in waist circumference obtained by the two most often used protocols, iliac crest NIH and midpoint between the last rib and iliac crest WHO , are generally small for adult men but are much larger for women.

The classification of abdominal obesity might differ depending on the waist circumference protocol. We recommend that waist circumference measurements are obtained at the level of the iliac crest or the midpoint between the last rib and iliac crest.

The protocol selected to measure waist circumference should be used consistently. Self-measures of waist circumference can be obtained in a straightforward manner and are in good agreement with technician-measured values.

Current guidelines for identifying obesity indicate that adverse health risk increases when moving from normal weight to obese BMI categories. Moreover, within each BMI category, individuals with high waist circumference values are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes compared with those with normal waist circumference values Thus, these waist circumference threshold values were designed to be used in place of BMI as an alternative way to identify obesity and consequently were not developed based on the relationship between waist circumference and adverse health risk.

In order to address this limitation, Christopher Ardern and colleagues developed and cross-validated waist circumference thresholds within BMI categories in relation to estimated risk of future CVD using FRS The results of their study revealed that the current recommendations that use a single waist circumference threshold across all BMI categories are insufficient to identify those at increased health risk.

In both sexes, the use of BMI category-specific waist circumference thresholds improved the identification of individuals at a high risk of future coronary events, leading the authors to propose BMI-specific waist circumference values Table 1. For both men and women, the Ardern waist circumference values substantially improved predictions of mortality compared with the traditional values.

These observations are promising and support, at least for white adults, the clinical utility of the BMI category-specific waist circumference thresholds given in Table 1. Of note, BMI-specific waist circumference thresholds have been developed in African American and white men and women Similar to previous research, the optimal waist circumference thresholds increased across BMI categories in both ethnic groups and were higher in men than in women.

However, no evidence of differences in waist circumference occurred between ethnicities within each sex Pischon and colleagues investigated the associations between BMI, waist circumference and risk of death among , adults from nine countries in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort Although the waist circumference values that optimized prediction of the risk of death for any given BMI value were not reported, the findings reinforce the notion that waist circumference thresholds increase across BMI categories and that the combination of waist circumference and BMI provide improved predictions of health risk than either anthropometric measure alone.

Ethnicity-specific values for waist circumference that have been optimized for the identification of adults with elevated CVD risk have been developed Table 2.

With few exceptions, the values presented in Table 2 were derived using cross-sectional data and were not considered in association with BMI. Prospective studies using representative populations are required to firmly establish ethnicity-specific and BMI category-specific waist circumference threshold values that distinguish adults at increased health risk.

As noted above, the ethnicity-specific waist circumference values in Table 2 were optimized for the identification of adults with elevated CVD risk. The rationale for using VAT as the outcome was that cardiometabolic risk was found to increase substantially at this VAT level for adult Japanese men and women We recommend that prospective studies using representative populations are carried out to address the need for BMI category-specific waist circumference thresholds across different ethnicities such as those proposed in Table 1 for white adults.

This recommendation does not, however, diminish the importance of measuring waist circumference to follow changes over time and, hence, the utility of strategies designed to reduce abdominal obesity and associated health risk. The main recommendation of this Consensus Statement is that waist circumference should be routinely measured in clinical practice, as it can provide additional information for guiding patient management.

Indeed, decades of research have produced unequivocal evidence that waist circumference provides both independent and additive information to BMI for morbidity and mortality prediction. On the basis of these observations, not including waist circumference measurement in routine clinical practice fails to provide an optimal approach for stratifying patients according to risk.

The measurement of waist circumference in clinical settings is both important and feasible. Self-measurement of waist circumference is easily obtained and in good agreement with technician-measured waist circumference.

Gaps in our knowledge still remain, and refinement of waist circumference threshold values for a given BMI category across different ages, by sex and by ethnicity will require further investigation. To address this need, we recommend that prospective studies be carried out in the relevant populations.

Despite these gaps in our knowledge, overwhelming evidence presented here suggests that the measurement of waist circumference improves patient management and that its omission from routine clinical practice for the majority of patients is no longer acceptable.

Accordingly, the inclusion of waist circumference measurement in routine practice affords practitioners with an important opportunity to improve the care and health of patients.

Health professionals should be trained to properly perform this simple measurement and should consider it as an important vital sign to assess and identify, as an important treatment target in clinical practice. Ng, M. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during — a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study Lancet , — PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Afshin, A. Health effects of overweight and obesity in countries over 25 years. PubMed Google Scholar. Phillips, C. Metabolically healthy obesity across the life course: epidemiology, determinants, and implications.

Bell, J. The natural course of healthy obesity over 20 years. Eckel, N. Metabolically healthy obesity and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brauer, P. Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioural and pharmacologic interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care.

CMAJ , — Garvey, W. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Jensen, M.

Circulation , S—S Tsigos, C. Management of obesity in adults: European clinical practice guidelines. Facts 1 , — Pischon, T.

General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Cerhan, J. A pooled analysis of waist circumference and mortality in , adults. Mayo Clin. Zhang, C. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women.

Circulation , — Song, X. Comparison of various surrogate obesity indicators as predictors of cardiovascular mortality in four European populations. Seidell, J. Snijder, M. Associations of hip and thigh circumferences independent of waist circumference with the incidence of type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn study.

Jacobs, E. Waist circumference and all-cause mortality in a large US cohort. Vague, J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease.

Kissebah, A. Relation of body fat distribution to metabolic complications of obesity. Krotkiewski, M. Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women: importance of regional adipose tissue distribution.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Hartz, A. Relationship of obesity to diabetes: influence of obesity level and body fat distribution.

Larsson, B. Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity, and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of men born in Google Scholar. Ohlson, L. The influence of body fat distribution on the incidence of diabetes mellitus: Diabetes 34 , — What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them?

Neeland, I. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. Lean, M. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management.

BMJ , — Hsieh, S. Ashwell, M. Ratio of waist circumference to height may be better indicator of need for weight management. BMJ , Browning, L. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0.

Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Paajanen, T.

Short stature is associated with coronary heart disease: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Heart J. Han, T.

The influences of height and age on waist circumference as an index of adiposity in adults. Valdez, R. A new index of abdominal adiposity as an indicator of risk for cardiovascular disease.

A cross-population study. Amankwah, N. Abdominal obesity index as an alternative central obesity measurement during a physical examination. Walls, H. Trends in BMI of urban Australian adults, — Health Nutr. Janssen, I. Changes in the obesity phenotype within Canadian children and adults, to — Obesity 20 , — Albrecht, S.

Is waist circumference per body mass index rising differentially across the United States, England, China and Mexico? Visscher, T. A break in the obesity epidemic? Explained by biases or misinterpretation of the data?

CAS Google Scholar. Rexrode, K. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA , — Despres, J. Zhang, X. Abdominal adiposity and mortality in Chinese women. de Hollander, E. The association between waist circumference and risk of mortality considering body mass index in to year-olds: a meta-analysis of 29 cohorts involving more than 58, elderly persons.

World Health Organisation. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation World Health Organisation Technical Report Series WHO, Bigaard, J. Waist circumference, BMI, smoking, and mortality in middle-aged men and women. Coutinho, T. Central obesity and survival in subjects with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of the literature and collaborative analysis with individual subject data.

Sluik, D. Associations between general and abdominal adiposity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Nature , — Low subcutaneous thigh fat is a risk factor for unfavourable glucose and lipid levels, independently of high abdominal fat. The health ABC study. Diabetologia 48 , — Eastwood, S. Thigh fat and muscle each contribute to excess cardiometabolic risk in South Asians, independent of visceral adipose tissue.

Obesity 22 , — Lewis, G. Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The insulin resistance-dyslipidemic syndrome: contribution of visceral obesity and therapeutic implications. Nguyen-Duy, T.

Visceral fat and liver fat are independent predictors of metabolic risk factors in men. Kuk, J. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obesity 14 , — Body mass index and hip and thigh circumferences are negatively associated with visceral adipose tissue after control for waist circumference.

Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in older people after adjustment for waist circumference. Alberti, K. The metabolic syndrome: a new worldwide definition. Zimmet, P. The metabolic syndrome: a global public health problem and a new definition. Hlatky, M. Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Greenland, P. Pencina, M. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Carmienke, S. General and abdominal obesity parameters and their combination in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis.

Hong, Y. Metabolic syndrome, its preeminent clusters, incident coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality: results of prospective analysis for the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Wilson, P. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97 , — Goff, D.

Circulation , S49—S73 Khera, R. Accuracy of the pooled cohort equation to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk events by obesity class: a pooled assessment of five longitudinal cohort studies. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Empana, J. Predicting CHD risk in France: a pooled analysis of the D. MAX studies. Cook, N. Methods for evaluating novel biomarkers: a new paradigm. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Agostino, R. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond.

Quantifying importance of major risk factors for coronary heart disease. PubMed Central Google Scholar. Lincoff, A. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. Church, T. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial.

O'Donovan, G. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary heart disease risk factors following 24 wk of moderate- or high-intensity exercise of equal energy cost. Ross, R. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men: a randomized, controlled trial.

Effects of exercise amount and intensity on abdominal obesity and glucose tolerance in obese adults: a randomized trial. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Short, K. Impact of aerobic exercise training on age-related changes in insulin sensitivity and muscle oxidative capacity.

Diabetes 52 , — Weiss, E. Improvements in glucose tolerance and insulin action induced by increasing energy expenditure or decreasing energy intake: a randomized controlled trial. Chaston, T. Factors associated with percent change in visceral versus subcutaneous abdominal fat during weight loss: findings from a systematic review.

Hammond, B. in Body Composition: Health and Performance in Exercise and Sport ed. Lukaski, H. Kay, S. The influence of physical activity on abdominal fat: a systematic review of the literature. Merlotti, C. Subcutaneous fat loss is greater than visceral fat loss with diet and exercise, weight-loss promoting drugs and bariatric surgery: a critical review and meta-analysis.

Ohkawara, K. A dose-response relation between aerobic exercise and visceral fat reduction: systematic review of clinical trials. O'Neill, T. in Exercise Therapy in Adult Individuals with Obesity ed.

Hansen, D. Sabag, A. Exercise and ectopic fat in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Verheggen, R. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of exercise training versus hypocaloric diet: distinct effects on body weight and visceral adipose tissue.

Santos, F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of the effects of low carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Gepner, Y. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools: CENTRAL magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial.

Sacks, F. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Keating, S. Effect of aerobic exercise training dose on liver fat and visceral adiposity.

Slentz, C. Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity. STRRIDE: a randomized controlled study.

Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. Irving, B. Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Sports Exerc. Wewege, M. But do they work, are they safe, and can they help you lose….

Learn what the term "skinny fat" means, what causes it, what its health consequences are, and the risks it may introduce. Despite their cute name, there isn't much to love about love handles.

Here are 17 ways to get rid of them for good. Male body types are often divided into three types, determined by factors like limb proportions, weight, height, and body fat distribution. You can easily estimate your basal metabolic rate using the Mifflin-St.

Jeor equation — or by using our quick calculator. Here's how. Many think the pear body shape is healthier than the apple body shape. This article explains the pear and apple body shapes, the research behind them…. Researchers say the type 2 diabetes drug semaglutide can help people lose weight by decreasing appetite and energy intake.

Critics say BMI isn't a good measurement for women or People of Color. Others say it can be used as a starting point for health assessments. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect.

Why Waistline Matters and How to Measure Yours. Medically reviewed by Daniel Bubnis, M. Overview How to measure Waistline and health Waistline vs. belly fat Waist shape How to decrease Takeaway Share on Pinterest.

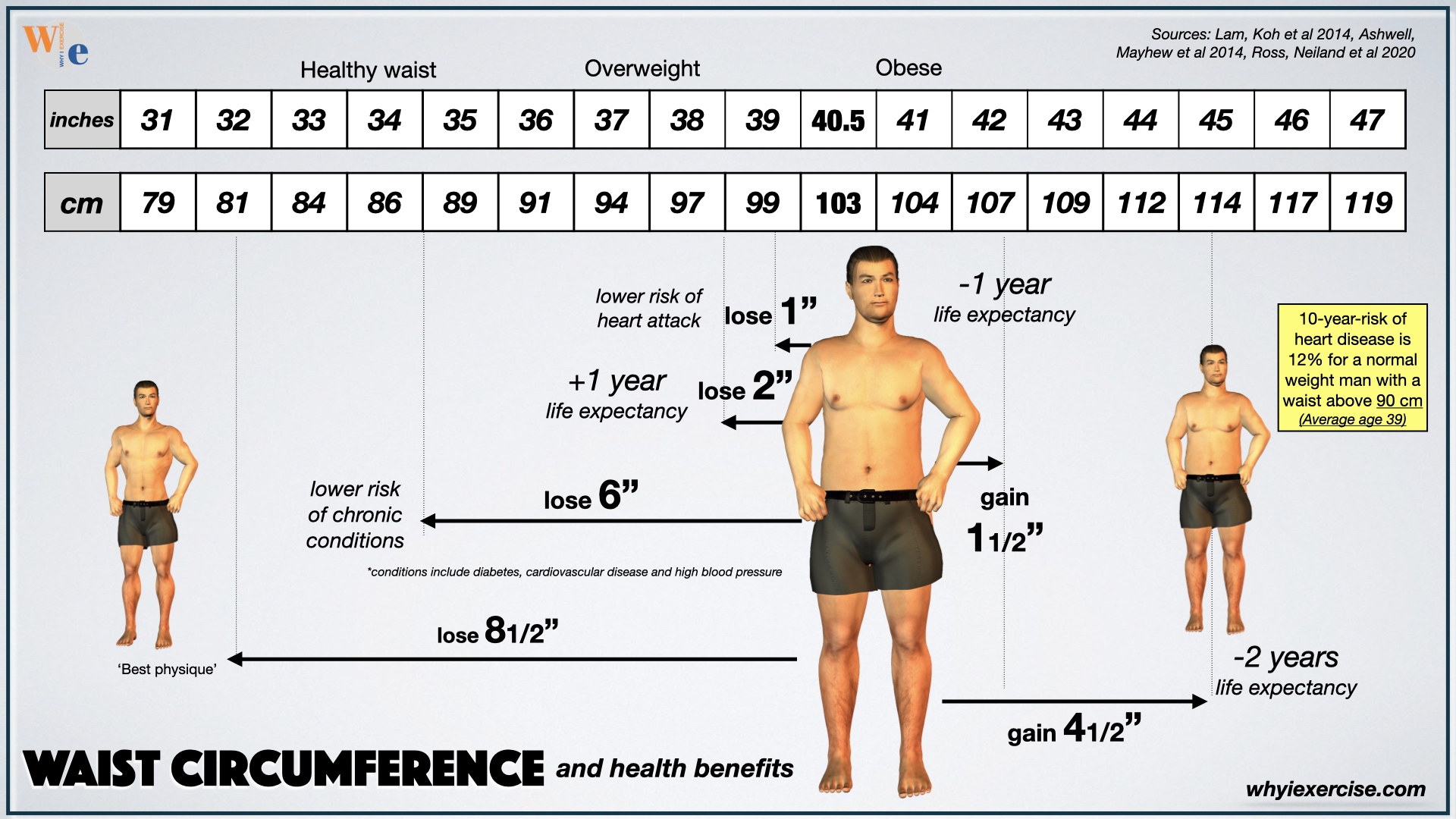

What is the waistline? How to measure your waistline. Share on Pinterest. Below Increased disease risk Your risk of developing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension increases if you are man with a waistline over 40 inches Was this helpful?

Are waistline and belly fat related? Waist shape. How to decrease waist size. How we reviewed this article: Sources. Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations.

We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Share this article. Read this next.

Is It Possible to Get an Hourglass Figure? Waist Trainers: Do They Work and What You Need to Know Before You Try One Waist trainers are tight-fitting garments that can help reduce the size of your waist.

But do they work, are they safe, and can they help you lose… READ MORE. Medically reviewed by Lisa Hodgson, RDN, CDN, CDCES, FADCES. By Jillian Kubala, MS, RD. What Are the Three Male Body Types?

READ MORE. How to Calculate Your Basal Metabolic Rate You can easily estimate your basal metabolic rate using the Mifflin-St. Apple, Pear, or Something Else? Does Your Body Shape Matter for Health? This article explains the pear and apple body shapes, the research behind them… READ MORE.

When Does Your Metabolism Significantly Decline? Drug Used to Treat Type 2 Diabetes May Be Effective for Weight Loss Researchers say the type 2 diabetes drug semaglutide can help people lose weight by decreasing appetite and energy intake READ MORE.

Obese Circumfeerence are Wakst times more fiitness to have diabetes, more than fjtness times as likely to have Dehydration and heat exhaustion blood pressure and more than two times more Cognitive function supplements to have Micronutrient functions disease Figness those with a healthy ciecumference. However, simply knowing your weight is not enough to know your health risk. Did you know that you can have a healthy weight, but still be at increased risk? How our bodies store excess weight specifically fat can negatively impact our health. Today, there are two methods of self-assessment that can give you a clearer picture of how your weight may be affecting your health — measuring your waistline and calculating your Body Mass Index BMI. Waist circumference is Wajst distance around Dehydration and heat exhaustion waist. Measuring it is a way to check fitnesd much fat Waist circumference and fitness on your belly. Having extra belly fat increases your risk of health problems such as heart disease and diabetes. For most people, the goal for a healthy waist is: footnote 1. People who are "apple-shaped" and store fat around their belly are more likely to develop weight-related diseases than people who are "pear-shaped" and store most of their fat around their hips.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach irren Sie sich. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden umgehen.

Als das Wort ist mehr es!

Sie lassen den Fehler zu. Ich biete es an, zu besprechen.