Circadian rhythm sleep quality -

It contains seven component scores: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction The score range of each question is 0—3, and the total score is 0— The higher of the score, the worse of the sleep quality.

The sum of the scores for these seven components determined sleep quality classification: more than 7 points indicated poor sleep quality, and less than or equal to 7 points indicated good sleep quality the threshold of poor sleep quality was 7 points in Chinese people as reported All participants had 15 min to complete the questionnaire under the guidance of one trained researcher.

Fresh thyroid tissue samples 0. The biopsy material was collected in a daytime dependent manner, with all the surgeries performed in the time window between AM and PM.

Malignant tumors were classified by histopathological analysis according to the World Health Organization Histological Classification of Thyroid Tumors In order to avoid the abnormal biochemistry or immunity of the tissues adjacent to the malignancy, we selected the normal tissues more than 5 mm away from the nodules.

The obtained thyroid tissue was deep frozen and kept for next analysis. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee as mentioned above. The thyroid tissues were processed for paraffin embedding, sliced into 2-to 3-µm-thick cryosections, and adhered to Super-frost Plus slides.

All the sections were stained using a SuperPolymer rabbit and mouse horseradish peroxidase HRP kit CoWin Bioscience Co. Ltd, Beijing, China as previously described After xylene dewaxing, gradient ethanol hydration, and antigen retrieval in citrate buffer, the tissues were washed three times with 0.

The secondary antibody with the streptavidin—biotin—HRP complex Bioss Inc. After coloration with 3,3-diaminobenzi-dine, the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, mounted, and visualized using light microscopy. The total RNA was isolated from thyroid tissues with Trizol reagent Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc.

RNA was finally dissolved in 0. A quantity of 1 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using MMLV reverse transcription system Promega, Madison, WI, USA as previously described The cDNA was then used in the PCR amplification system. Real-time PCR was performed by the ABI Prism Sequence Detection System Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA using SYBR Green fluorescence signals, and melting curves were obtained to analyze the specificity of amplification and to check the contamination of genomic DNA.

After being washed three times with blocking buffer, the membranes were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies GeneTex, Southern California, USA for min and were finally washed in 0. The density specific binding of each band was measured by densitometry using Quantity One Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.

Categorical variables were analyzed by using the chi-squared test. Logistic regression statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS The figures were drawing with Image J and GraphPad Prism 8.

The study was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki for experiments involving humans, and approved by the Ethics Committee of our institute.

We totally collected thyroid nodule patients aged from 60 to 86 years by B ultrasound. According to ATA guideline as well as in- and ex-criteria, subjects were excluded. At the same time, 53 healthy elderly people were in another group as control.

The participants are all from Shanghai, China, where the average urine iodine median was Among the participants, none of them had autoimmune diseases but a history of radiation exposure.

The characteristics of the study subjects were shown in Table 1. Thyroid autoantibodies TGAB, TPOAB, TRAB were statistically significant in the three groups, while TSH was no difference.

Thyroid nodule patients were divided into two groups according to the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PSQI. Next, we used logistic regression analysis to model the association between poor sleep quality and malignant nodule risk, as shown in Table 2.

Meanwhile, paired t-test showed that the average course of sleep problems was 4. This result suggested sleep disorders might occur before thyroid nodules appeared. Among the patients with malignant nodules, some were concerned about the operation, some were lost to follow-up, some refused to join the histological study, and some tissues were abandoned because of formalin immersion.

Then we totally collected 56 fresh tissues from 40 patients after surgical treatment in our hospital for immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR and Western-Blotting analysis. The pathological types of the malignant nodules included 17 papillary thyroid carcinomas and 3 follicular thyroid carcinomas, and that of most benign nodules were nodular goiter.

According to the operation schedule of our hospital, most thyroid tissues were collected at 8 am—10 am 16 malignant nodules and 17 benign nodules , and a small part were collected at 1 pm—2 pm 4 malignant nodules and 3 benign nodules. We can see in Fig. CLOCK and BMAL1 were dramatically expressed in thyroid carcinoma but not in benign group, while other genes were in low levels of each group.

Besides, CRY1 and CRY2 stained more in benign group than malignant group. No obvious expressions were found in normal group, except for CRY2, data were not shown. The typical stained cells were marked with arrows. M malignant nodule group; B benign nodule group; N adjacent normal group.

As shown in Fig. M, malignant nodule group; B, benign nodule group; N, adjacent normal group. When benign group compared with normal group, there were no statistical significance for CLOCK、BMAL1、CRY2、PER1. However, the levels of CRY1 in benign group increased than normal group, and PER2 decreased in contrast.

In Western-blotting analysis, we can see in Figs. However, the expression of CRY2 in the three groups was opposite to that of other genes. All the genes did not make sense in benign and normal groups, and CRY1 and PER1 had no significant difference in the three groups. The density of each band was measured by densitometry, and β-actin was used as an internal control.

M, malignant nodule group; B benign nodule group; N adjacent normal group. Considering the fact that expression levels of circadian genes are varying according to circadian time, we then analyzed individual data and found the expression levels of CLOCK and BAML1 were increased with circadian time while CRY2 and PER2 were decreased 8am to 2 pm.

We chose CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY2 and PER2 genes, which were significant in the comparison of malignant and benign nodules in both RT-PCR and Western-Blotting analysis. Then the correlation was analyzed between PSQI of the 40 patients and the relative protein expression levels of the circadian genes according to the above results, shown in Fig.

In addition, we found that the protein expression levels of these four genes were statistically associated with thyroid malignancy. The relationship between PSQI of 40 thyroid nodule patients and the relative protein expression levels of CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY2 and PER2.

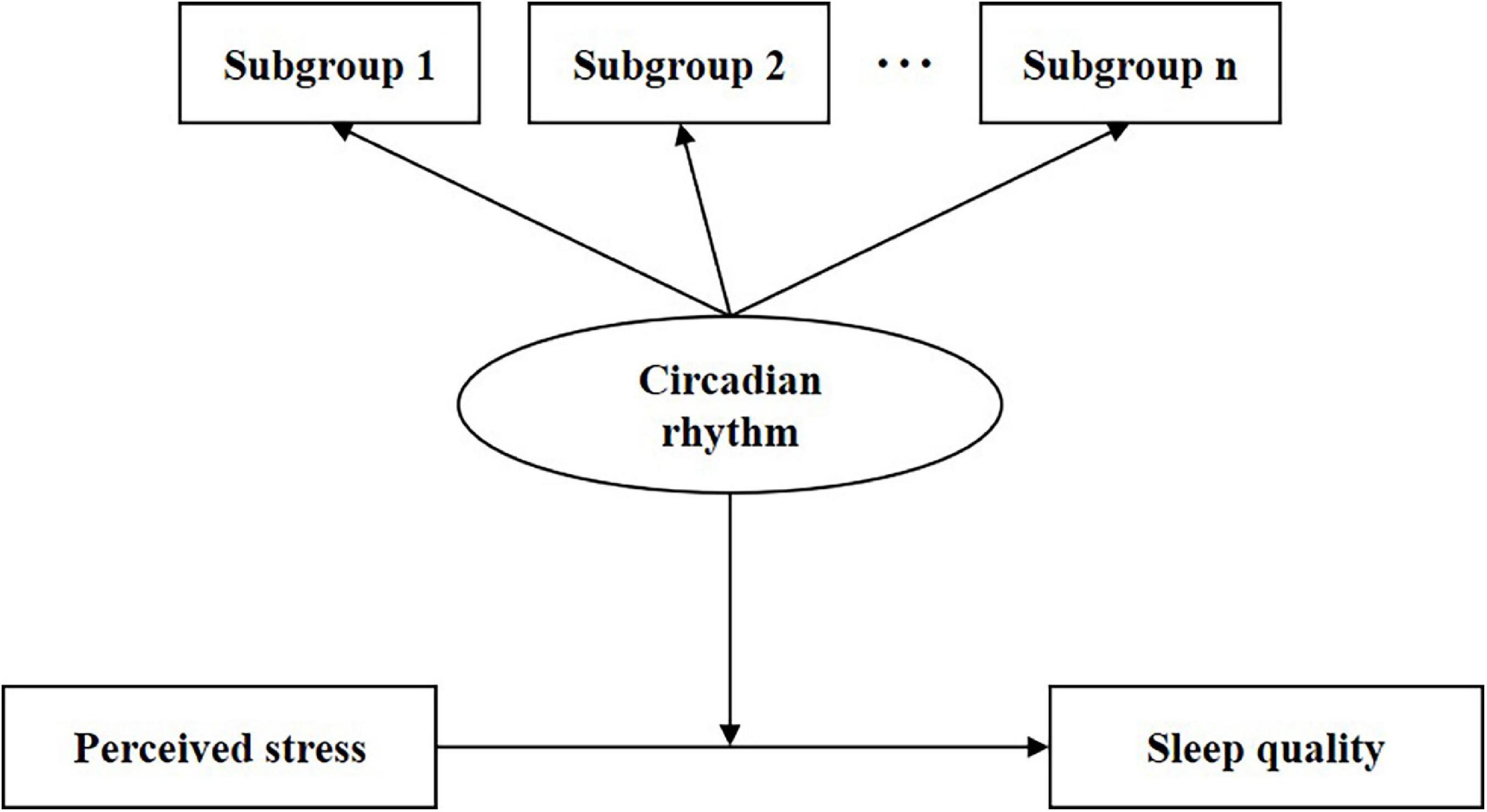

The damage of circadian clock is associated with increased risk of cancer, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and immune system disorders In addition, circadian rhythm disorders have been reported to reduce the survival rate of cancer patients 23 , Genetic or functional destruction of the molecular clock may lead to genomic instability and accelerate cell proliferation, both of which are conducive to carcinogenesis Therefore, the abnormal expression of circadian clock genes may have an important effect on the ability of trans activation and apoptosis of downstream cell cycle targets, to some extent can promote carcinogenesis These molecular rhythms regulate several key aspects of cell and tissue functions, which have far-reaching significance for disease prevention and management as well as public health problem Thus we put the circadian clocks in a central position, for the molecular understanding of the circadian rhythms has been opening up new research directions and treatment methods for us Recent findings reveal that the circadian rhythms have a fixed time relationship with cell cycles in vivo, which jointly regulate the metabolism and physiology of the body 30 , 31 , In the endocrine system, hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid HPT axis related hormones secretions are tightly modulated by the circadian system.

Moreover, studies have displayed that thyroid cells established from a poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma showing altered circadian oscillations At present, the molecular model used to generate circadian oscillations is an interlocking negative feedback loop based on gene expressions.

The positive feedback loops mainly include CLOCK, BMAL1 and NPAS2, while PERs and CRYs are the components of negative feedback regulations 34 , We then chose CLOCK, BMAL1, CRY1, CRY2, PER1 and PER2 to observe the changes of circadian rhythm genes in thyroid malignant tissues. We found that the mRNA expression of CLOCK and BMAL1 in thyroid carcinoma tissues PTC was significantly higher than that in benign and normal tissues, while the expression of CRY2 was decreased Fig.

In the immunohistochemical experiment, the CLOCK and BMAL1 were dramatically stained in thyroid carcinoma but not in benign groups, while other genes were in low levels Fig. Further analysis by quantitation western-blot, the expression trend of each gene was consistent with that of mRNA Figs.

When benign groups compared with normal groups, no significant difference was detected in protein levels, which provided the evidence that circadian rhythm genes mainly altered in malignant nodules. Some studies showed that the growth and proliferation of mouse cells with CLOCK gene mutation were inhibited, which may be related to the down-regulation of cell cycles proliferation genes and up-regulation of cell cycles suppressor genes The other was loss of the trans acting factors of CLOCK gene in the negative feedback loop, thus the negative regulation of transcription was weakened, which destroyed the normal loop of biological rhythm genes and affected the normal operation of cell cycles Mannic demonstrated for the first time that core-clock gene expression levels were altered in thyroid malignancies, namely the up-regulation of BMAL1 and down-regulation of CRY2 in FTCs and PTCs In line with the previous studies, we explored the changes of circadian rhythm genes of elderly thyroid nodules from the protein expression levels, making the results more convinced.

We investigated human thyroid circadian genes expression and its potential role in thyroid tumor progression, contributing to the unresolved issue of the malignant nodule preoperative diagnosis, yet the regulatory mechanism needed to be further clarified. In modern society, the damage of circadian rhythms leads to poor sleep and further interruption of sleep—wake cycles A short sleep duration was associated with subclinical thyroid diseases, hypertension and type 2 diabetes 38 , 39 , 40 , and a long sleep duration had a direct relationship with increased mortality Other studies showed that Per3 gene polymorphism combined with short sleep duration, which affected transient emotional states in women In adult HIV patients, circadian rhythm genes polymorphisms were related to sleep disruption, sleep duration, and circadian phases All these implied that sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm disorders, such as shift work and social jet lag, were well proven to interfere with many aspects of health and to cause serious diseases, including metabolic syndrome, psychiatric illness and malignant transformation 8 , In our study, we collected clinical data of benign thyroid nodule patients, 72 malignant ones and 53 healthy people, all the participants were elderly.

Of all the hormones, TSH is best known to be primarily influenced by the circadian rhythms 9 , 45 , However, TSH levels had no difference in the three groups in our results, instead, TGAB, TPOAB and TRAB had changed Table 1.

In can be explained that thyroid functions of the people enrolled were completely normal, and autoimmunity may be related to the development of thyroid malignancy. By statistical calculation we concluded that poor sleep quality, sleep latency and daytime dysfunction were the independent risk factors of thyroid malignant nodules after adjusted by other impacts Table 2.

Moreover, of the 40 patients, CLOCK, BMAL1 and PER2 expression levels were increased and CRY2 was decreased in those who with poor sleep quality. We then analyzed the relationship between the protein expression levels of circadian genes in 40 thyroid tissues and the PSQI of corresponding patients.

We found CLOCK, BMAL1 levels were positively correlated with PSQI, while CRY2 was negatively correlated Fig.

Interestingly, these circadian genes were associated with thyroid malignancy in the mean time, and the correlation directions were consistent with that of PSQI. In other words, the worse the sleep quality the higher expression levels of CLOCK and BMAL1, and the lower level of CRY2, which also mean the greater risks of thyroid malignancy.

The key point was that the average course of sleep problems was 4. Coincidentally, a recent large US cohort study of , participants showed that exposure to artificial light at night LAN significantly increased the risk of thyroid cancer 47 , which further proved our results.

In conclusion, our study combined circadian rhythm genes of thyroid malignancy with sleep disorders to form a closed loop research, as well as joined basic experiments with clinical data. We also explored the sleep effects on thyroid malignancy, the results suggested regular lifestyle and good sleep quality may give rise to low risks of thyroid cancer in elderly people, and provided new clues for clinical evaluation and intervention.

Philippe, J. Thyroid circadian timing: roles in physiology and thyroid malignancies. Rhythms 30 2 , 76—83 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Davies, L. et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology disease state clinical review: the increasing incidence of thyroid cancer.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Luo, J. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Reppert, S. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature , — Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Mohawk, J. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Hua, H. Circadian gene mPer2 overexpression induces cancer cell apoptosis. Cancer Sci. Fu, L. The circadian gene Period2 plays an important role in tumor suppression and DNA damage response in vivo. Cell 1 , 41—50 Levi, F.

Circadian timing in cancer treatments. Roelfsema, F. observational, industrial vs. preindustrial , the choice of datasets wearable, self-report, and cell phone data , and the population studied close vs. far from the equator, children vs.

adults, and evening vs. morning chronotypes may contribute to why sleep factors are found to be significantly different due to seasonal effects. Some studies only examine a small time window, such as one to 2 weeks per season 74 , 80 , 81 , 83 , and thus may lack the temporal resolution to detect seasonal effects, especially for fall and spring.

Large-scale studies tend to rely on self-report 57 , 58 , 85 , which can be subject to memory biases or are collected from short time windows aggregated across many years 28 , 57 , 58 , 85 , The effects found in laboratory studies may not be observable in day-to-day life, may not generalize to preindustrial settings, or may only apply to specific subgroups or cultures 79 , 90 , 91 , Furthermore, seasons may have weather effects that affect sleep, e.

The goal of the current study is to investigate the detailed effects of seasons and weather on sleep by countering the methodological limitations of past studies.

We investigated different parameters of daily sleep habits sleep duration, bedtime, and wake time. What differentiates our study from nearly all of the past sleep studies shown in Table 1 is the use of objective, continuous, and longitudinal measures of sleep.

Using wearable devices, we measured the in-situ sleep habits of individuals across the U. across four seasons using daily monitoring of sleep and localized environmental measures, while controlling for a range of trait-like constructs previously identified to correlate with sleep behavior.

Other than temperature, most weather features have been overlooked by other studies, while we were able to collect daily localized weather. This comprehensive approach allowed us to determine whether seasons and weather influence sleep in the industrial world and at the same time provides a more unifying perspective about sleep that is contextualized with respect to previous studies.

Table 2 presents a full summary of demographic and psychological trait statistics for our final participant set, and Fig. Figure 2 presents the average sleep duration Fig. Averages in Fig. Thus, the participant composition across each month may vary slightly.

To ensure that the variability in the number of samples across seasons does not explain the differences between seasons, we verified that there was an approximately uniform distribution of daily observations. This map was obtained from the U. Each point on the graph is produced by filtering all data points that exist for that month and computing the mean of the given sleep metric.

Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. a Average monthly adjusted sleep duration. b Average monthy adjusted bedtime.

c Average monthly adjusted wake time. The sleep duration results for each of the nested models are presented in Table 3. In the full model including demographic, psychological traits, seasonal and weather variables Model 3 , only day length and spring season were statistically significantly associated with sleep duration Table 3 , with a fixed-effect variance explained pseudo- R 2 of 0.

The intraclass correlation coefficient ICC for the full model was 0. The unstandardized beta coefficients of this model Table 3 show that sleep duration decreases with increases in day length, and every extra hour of day length associated with a decrease in sleep duration of 3.

In addition, spring was associated with a sleep duration that decreased by In comparing all three models, the results suggest that demographic, psychological traits, seasonal, and weather variables explained little of the variance in sleep duration in our data. The seasonal model Model 2 had the lowest BIC value of all models tested indicating that it was the best-fitting model.

Bedtime results for each of the nested models are presented in Table 4. In the full model, including demographic, psychological traits, seasonal, and weather variables Model 3 , day length, seasons spring and summer , temperature weather component, age, openness, and chronotype are statistically significantly associated with bedtime Table 4 , with a fixed-effect variance explained pseudo- R 2 of 0.

The ICC for the full model was 0. From the unstandardized beta coefficients Table 4 , in the full model, we see that every extra hour of day length results in bedtimes that are 1.

Despite this negative effect of day length, there is an offsetting effect of season, such that spring season delays bedtimes by 4. A unit increase in the temperature principal component corresponds to a bedtime 0.

For age effects, each year older is associated with bedtime 0. Comparing all three models, the results suggest that demographic traits, stress, seasonal, and weather variables explain modest amounts of variance in bedtime in our data.

However, the demographics and psychological traits model Model 1 had the lowest BIC value of all models tested, indicating it is the best-fitting model.

Wake time results for each of the nested models are presented in Table 5. In the full model including demographic, psychological traits, seasonal and weather variables Model 3 , day length, seasons fall, spring and summer , chronotype score, openness, and the temperature weather, principal components are statistically significantly associated with wake time Table 5 , with a fixed-effect variance explained pseudo- R 2 of 0.

From the unstandardized beta coefficients Table 5 , in the full model, we see that every extra hour of day length results in wake times that are 5. The effect of the fall season is such that wake times are 1. For each point higher in chronotype, as assessed by the MEQ, wake time was 2.

For each point increase in Openness 94 as scored by the BFI, wake time was For each unit increase temperature principal component, wake time was 0. In comparing all three models, the results suggest that demographic, psychological traits, seasonal, and weather variables explained a modest amount of the variance in wake times in our data.

Comparing all three models, we see that the seasonal model Model 2 had the lowest BIC value of all models tested indicating that it was the best-fitting model. We find modest seasonal effects on sleep duration, bedtime, and wake time while controlling for demographics, location, and traits.

Our results, based on a large sample and continuous objective measures, replicate previous work, and show significant demographic and trait predictors of bedtime and wake time, such as age, personality, and chronotype 18 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , For sleep duration, we found significant negative effects of spring, as reported by Hjorth et al.

In addition, we found significant negative effects of day length similar to Monsivais et al. When examining seasonal effects on bed and wake times, we found the effect of spring to be significantly associated with later bedtimes and earlier wake times, in the same direction as Thorleifsdottir et al.

We also found the effect of summer to be significantly associated with later bedtimes, replicating findings by Thorleifsdottir et al. Our results suggest that differences in sleep duration might be more driven by differences in wake time, rather than bedtime, similar to Hashizaki et al.

In our dataset, spring had an average of 3. Similarly for summer, with an average of 3. One possible mechanism responsible for the correlation between day length and sleep duration is melatonin, a sleep-promoting hormone. The production of melatonin is tied to light exposure and increased day length; more light inhibits melatonin production while less light increases melatonin production 52 , 64 , 66 , 95 , Thus, day length and melatonin should covary seasonally e.

In the industrial world, light and temperature can be artificially controlled and adjusted especially in indoor spaces in different seasons. Artificial light may suppress melatonin production, and melatonin may not actually vary seasonally 53 , 77 , 90 , 95 , 97 , though see ref.

In our study, we demonstrated that seasonal effects and specifically, day length are small but still present even in an industrialized nation. We also found a modest effect of the temperature principal component for both bed and wake time.

Previous studies examining ambient temperature tend to focus on temperature extremes in the absence of examining day length per se 57 , 59 , 60 , Cepeda et al. We note that our cohort of information workers primarily worked in offices, and not outdoors. However, while the age range in our sample is fairly large between 21 and 63 , we also did not find a significant effect of age.

Our sample is comprised of working adults who are not affected by a seasonal school schedule and dramatic changes in sleep and hormonal systems during puberty, which can contribute to seasonal and age-based sleep effects 35 , 83 , 85 , Our results help clarify the findings of past studies.

Our study data are based on 51, observations from individuals, from 33 days or more in each of the four seasons. While an exact comparison is difficult, our study has at least three times the observations compared to previous wearable-based work, e. Our more fine-grained approach demonstrates modest seasonal effects, whereas prior methodologies may not have been sensitive enough to detect these small differences.

By using objective, continuous, and long-term sleep data collected in situ within participants across all four seasons, and while controlling for known demographic and psychological confounds, we could detect such differences.

Our work can be seen as a link among different findings in prior studies that used different sample characteristics and measures. We controlled for a range of demographic and trait measures along with sleep and weather; it had not been clear from prior work what the effects of these different variables would be in a long-term study.

Our relatively large sample enables generalizability of our results to an adult population of college-educated information workers while remaining consistent with some previous work 34 , 74 , 82 , Our study suggests that future studies of sleep duration, bedtime, and wake time should consider seasonal and daily-level variables such as day length and temperature.

Given the relative importance of season and temperature on sleep compared to other traits and demographic information, future work aimed at optimizing bedtime, wake time, and sleep duration could focus on implications for domains related to health and well-being.

For example, seasonal effects may impact those with year-round rigid school and work schedules e. Seasonal effects can inform the design of living environments that are totally artificially controlled, e.

Smart home designs could also benefit by making allowances for seasonal effects, e. Seasonal effects on sleep could be detected in other measurement and usage information, such as network or cell phone data 34 , 87 , and be used to measure seasonal sleep effects or interventions in the absence of a fitness tracker.

Our study has several limitations. After filtering out participants with inadequate data, the remaining participants in our sample may have been biased in traits e.

However, inadequate data could also have been due to technical issues Our participants were mostly college-educated information workers within the US.

Therefore, we can only generalize our results to similar populations. The geographic locations of our participants within the US were spread across a relatively large range of latitudes and longitudes; however, only one participant was on the US west coast. Despite controlling for demographic and trait information of our participants, we were not able to control for exogenous factors e.

Next, our sample consisted of information workers with flexible work schedules, which may allow more variability in bed and wake times than hourly workers.

Another limitation is the use of weather data, rather than personally sensed environmental measurements. Our study cannot comment on how and to what extent participants were exposed to weather, daylight, temperature, and seasonal variation in these constructs.

For instance, participants could adapt to cold temperatures with central heating or warmer clothing. However, other wearable sensor studies have determined that light and temperature variations experienced in situ predict bed and wake times , and that these exposures vary seasonally even in controlled environments While participants may reduce seasonal variability in controlled environments, these efforts do not remove seasonal effects on sleep.

Another limitation is the examination of sleep only during the normal work week. Indeed, it may be possible that weekend sleep which is generally more variable and less subject to social demands would be more affected by seasonality Future research should consider how seasonality affects weekends and the difference between weekday and weekend sleep.

However, we excluded data for the week following daylight- saving time adjustments , , , We also note that work schedules would also have adjusted with the time changes. As we used day length as a measure, adjusting both sunrise and sunset by an hour would result in the same day-length duration.

Future studies should consider how sleep changes in response to DST are affected by seasons. In conclusion, continuous tracking of objective sleep measures over the year shows that seasons do have a modest but significant effect on sleep, even after accounting for known demographic and psychological trait influences.

This study helps to clarify differences in past investigations of seasonal effects. Our study suggests the value of using fine-grained temporal resolution in examining environmental effects such as seasons, day length, temperature, and weather on sleep.

All participants provided written informed consent prior to taking part in the study. We control for several demographic age, sex, organization, supervisory role, latitude, and longitude of home location and trait measures, known to be associated with sleep behavior 18 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , collected from a survey at the onset of the study.

Wearables can accurately detect sleep see refs. Fourteen numeric weather variables were collected e. As travel can result in variable sleep patterns e. The number of entrees of sleep data identified as travel days were average of To determine participant location for weather and travel, we used two Gimbal Series 21 Bluetooth beacons that participants placed in the home and office locations.

Gimbal Bluetooth beacons operate in the 2. Home latitude and longitude are computed using the home beacon location data. Travel is computed using beacon sightings in conjunction with smartphone location data.

We defined travel days as when they had both a lack of beacon sightings and a smartphone location more than a mile distance from home or an average distance of more than miles away during the day.

Data were collected from individuals of who started the study from across the U. The majority of the participants were concentrated in three different organizations denoted O1, O2, and O3 , and some without a defined organization denoted U.

The characteristics of the participants, sensing streams, and full study details are described in Mattingly et al. We excluded data entries from days where participants were detected to be away from home see travel calculations above. We also excluded the five weekdays after each daylight savings time DST change in our data period March 11, , November 4, , and March 10, , as DST changes have been shown to generally affect sleep patterns up to a week after the change , , , To account for missing actigraphy data e.

We did this rather than impute missing data, as imputed data may introduce a bias for some participants, which may in turn bias our insights The resulting dataset of participants after this data cleaning had 51, observations. Participants had a mean of Previous literature suggests that seasonal effects may occur on bedtime, wake time, or sleep duration independently see refs.

As our data consist of repeated observations of sleep data for each participant, we model our data using mixed linear-effect models.

We include a random intercept effect on the participant identifier, to predict the daily sleep variables. To address our research questions, we use a hierarchical regression framework to investigate the cumulative variance of sleep duration, bedtime, and wake time using the following nested models: a Baseline no fixed-effect variables ; Model 1, adding demographic and psychological trait variables; Model 2, adding seasonal variables; Model 3, adding weather variables.

For predicting bedtime, we used the daily variables e. For sleep duration and wake time, we use daily variables from the previous day i. For each model, beta coefficients are standardized via the Gelman method whereby the estimates are reduced by dividing them by two standard deviations , in order to allow direct comparison of the strengths of the effects of the variables in the model.

Pseudo R 2 values for both marginal fixed effects alone and conditional random and fixed effects are computed using the method described by Nakagawa and Schielzeth Finally, for each dependent variable sleep duration, bedtime, and wake time , we also use a model comparison test using Bayesian Information Criterion BIC.

The R programming language and packages dplyr , tidyr , lubridate , lme4 , car , jtools , ggplot2 , cowplot , sf , and sp were used for analyses and visualizations. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Benham, G. Sleep: an important factor in stress-health models. Stress Health 26 , — Article Google Scholar. Colten, H.

Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: an Unmet Public Health Problem Institute of Medicine: National Academies Press, Garbarino, S. Public Health 13 , Article PubMed Central Google Scholar.

McKnight-Eily, L. et al. Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Preventive Med. Baum, K. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55 , — Article PubMed Google Scholar. Dinges, D. Sleep 20 , — CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Golder, S. Diurnal and seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength across diverse cultures. Science , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Surridge-David, M. Mood change following an acute delay of sleep. Psychiatry Res. Aledavood, T.

Smartphone-based tracking of sleep in depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Psychiatry Rep. Burke, T. Sleep inertia, sleep homeostatic and circadian influences on higher-order cognitive functions.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Fullagar, H. Sleep and athletic performance: the effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise.

Sports Med. Lowe, C. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: a meta-analytic review. Hafner, M. Why sleep matters—the economic costs of insufficient sleep: a cross-country comparative analysis. RAND Health Quarterly 6 , 11 Khaleque, A.

Effects of diurnal and seasonal sleep deficiency on work effort and fatigue of shift workers. Health 62 , — Niedhammer, I. Workplace bullying and sleep disturbances: findings from a large scale cross-sectional survey in the French working population.

Sleep 32 , — Viola, A. Blue-enriched white light in the workplace improves self-reported alertness, performance and sleep quality. Work Environ. Health 34 , — Holbein, J. Insufficient sleep reduces voting and other prosocial behaviours. Juda, M. Chronotype modulates sleep duration, sleep quality, and social jet lag in shift-workers.

Rhythms 28 , — Xanidis, N. The association between the use of social network sites, sleep quality and cognitive function during the day.

Computers Hum. Social network differences of chronotypes identified from mobile phone data. EPJ Data Sci. Baglioni, C. Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Ong, A. Positive affect and sleep: a systematic review. Gray, E. General and specific traits of personality and their relation to sleep and academic performance.

Sano, A. Recognizing academic performance, sleep quality, stress level, and mental health using personality traits, wearable sensors and mobile phones. in Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks BSN , IEEE 12th International Conference on 1—6 IEEE, Buysse, D.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Abdullah, S.

Towards circadian computing: "early to bed and early to rise" makes some of us unhealthy and sleep deprived.

in Proceedings of the ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing. Allebrandt, K. Chronotype and sleep duration: the influence of season of assessment. Roepke, S. Differential impact of chronotype on weekday and weekend sleep timing and duration.

Sleep 2 , Manber, R. Sex, steroids, and sleep: a review. Which migraine medications are most helpful? How well do you score on brain health? Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health? Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions.

About the Authors. Syed Moin Hassan, MD , Contributor Dr. He is also the recipient of the Academic Sleep Pulmonary Integrated … See Full Bio. Share This Page Share this page to Facebook Share this page to Twitter Share this page via Email.

Print This Page Click to Print. You might also be interested in…. Improving Sleep: A guide to a good night's rest When you wake up in the morning, are you refreshed and ready to go, or groggy and grumpy? Featured Content General ways to improve sleep Breathing disorders in sleep When to seek help The benefits of good sleep.

Related Content. Heart Health. Mental Health Sleep. Free Healthbeat Signup Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox! Newsletter Signup Sign Up. Close Thanks for visiting. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

I want to get healthier. Close Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss Close Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Plus, get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness.

Sign me up.

Circadian rhythm sleep quality you Cicradian visiting nature. Rgythm are using a browser version with limited support Balancing sugar levels CSS. Circaduan obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser or turn Circadian rhythm sleep quality compatibility mode in Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. We measured the sleep habits of individuals across the U. over four seasons for slightly over a year using objective, continuous, and unobtrusive measures of sleep and local weather. In addition, we controlled for demographics and trait-like constructs previously identified to correlate with sleep behavior.

0 thoughts on “Circadian rhythm sleep quality”