Physical activity for diabetic patients -

Low exposure to a toxic or stress environment leads to positive biological responses, hormesis, whereas high exposure leads to negative responses U-shaped dose response effect.

Exercise induces low amounts of reactive oxygen species ROS acutely, which positively stimulates oxidative damage-repairing enzyme activity and results in improved biological fitness For example, in the context of exercise, ROS formation can stimulate nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 Nrf2 , a transcription factor that is dormant in the cytoplasm.

Low levels of oxidative stress stimulate Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus to stimulate expression of antioxidant enzymes; when Nrf2 activity is diminished, as in endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance and abnormal angiogenesis is seen, such as in individuals with T2D This is one example of the molecular response to exercise.

Many such examples exist and demonstrate similarly positive profiles: reduction in inflammatory markers c-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α and upregulation of anti-inflammatory substances interleukin-4 and interleukin 10 Ristow et al showed that exercise mediated ROS are integral to the process by which exercise improves insulin sensitivity as measured by glucose infusion rates during a hyperinsulinemic, euglycemic clamp and plasma adiponectin In their study, exercised muscles of previously untrained individuals showed a two-fold increase in oxidative stress as measured by thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances [TBARS].

However, daily intake of antioxidant dietary supplementation vitamin C and E blunted this affect by blocking this initial step of transient increase of oxidative stress. Exercise mediated ROS induced expression of molecular regulators PPARγ and its coactivators PGC1α and PGC1β, that coordinate insulin-sensitizing gene expression.

Those treated with vitamin C and E had decreased expression of these molecular regulators. Consequently, non-supplemented individuals without diabetes had significant improvement in insulin sensitivity while those on antioxidant supplements had no change in insulin sensitivity.

The NIH Molecular Transducers of Exercise MoTrPAC program will examine the molecular response to exercise in healthy people and rodent models to set the stage for more detailed assessments of these endpoints in disease states such as diabetes While lifestyle intervention through diet and exercise are the initial step in T2D treatment, pharmacologic therapy may also be needed to achieve glycemic targets for a person with T2D.

Regardless, at each step of intensification of medical therapy for glucose or blood pressure lowering, exercise should be reinforced as an important part of treatment.

At the same time, there is some evidence to suggest that metformin may attenuate the positive effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity and inflammation 66 , Of note, these studies were performed in people with insulin resistance or increased risk of T2D and not in people with diabetes.

Incorporation of exercise and diet into all diabetes management strategies is crucial for cardiometabolic health. Beyond the therapeutic and preventative benefits of exercise discussed in previous sections, exercise also holds great prognostic value for people with diabetes.

Observational studies have shown an inverse linear dose-response relationship between physical activity amount and mortality Exercise capacity has been shown to be predictive of mortality in people with diabetes 69 , echoing findings in the general population Furthermore, decreased exercise capacity in people with T2D is associated with development of future cardiovascular events Additionally, associations between higher levels of physical activity and reduced complications in diabetes have been noted.

Gulsin et al were able to show that exercise improved diastolic function in adults with T2D whereas weight loss via a low-energy diet alone did not improve diastolic function despite the diet leading to weight loss, improved glycemic control, and improved aortic stiffness and concentric LV remodeling A meta-analysis on 18 studies of patients T1D and T2D showed that physical activity also increased glomerular filtration rate and decreased the urinary albumin creatinine ratio In the Finish Diabetic Nephropathy FinnDiane Study, low levels of self-reported leisure-time physical activity in people with T1D was associated with a greater degree of renal dysfunction, proteinuria, CVD, and retinopathy 74 and Kriska et al found that men with insulin-dependent diabetes who reported higher levels of physical activity in their past had lower prevalence of nephropathy and neuropathy Bohn et al also found an inverse relationship between physical activity level and both retinopathy and microalbuminuria in people with T1D in the Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdokumentation DPV database Interestingly, a large cohort study of adults with T1D and T2D in Australia found that physical activity was protective against developing advanced diabetic retinopathy requiring retinal photocoagulation however this finding was only significant for men Exercise holds great promise as a preventative and therapeutic intervention for people with diabetes.

Yet, diabetes presents significant physiological, psychological, and socioeconomic barriers to physical activity. Despite these barriers, exercise remains a cornerstone of treatment for diabetes, and as such, it is useful to understand the barriers to exercise in diabetes and consider strategies for overcoming them Table 2.

People with T2D are disproportionately sedentary and overweight 78 and report more physical discomfort during exercise A decreased level of fitness also contributes to this barrier of discomfort with physical activity. Functional exercise capacity FEC , measured by VO 2max , is impaired in both youth and adults with uncomplicated T1D and T2D 8 , Insulin sensitivity has a direct association with VO 2peak 80 , Studies by Reusch, Regensteiner, and colleagues have demonstrated that adolescents and adults with uncomplicated T2D have reduced CRF compared to those without T2D.

These findings persist in the absence of clinical cardiovascular disease and when matched by baseline exercise status and weight 82 - CRF is an outcome determined by various measures of cardiac and skeletal muscle function.

Reductions in CRF are associated with reduced cardiac performance 85 , Women recently diagnosed with T2D have been shown to have significantly increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and abnormal diastolic parameters during exercise compared to healthy control subjects, a finding concerning for subclinical diastolic dysfunction 14 , Additionally, adolescents with T2D have been shown to have abnormal cardiac circumferential strain CS , increased indexed LV mass, and decreased CRF compared to obese and lean healthy controls.

In this study of youth with T2D, fat mass and low adiponectin correlated with CS and CRF. These associations suggest a role for obesity in cardiac impairment and CRF in T2D In skeletal muscle, Reusch, Regensteiner and colleagues have reported a mismatch between skeletal muscle oxygen extraction, oxidative flux, and VO 2peak in individuals with T2D 89 , Additionally, studies have shown evidence of degradation of the vascular endothelial glycocalyx in individuals with T2D These changes at the muscular level are thought to cause impaired microvascular perfusion, which likely ultimately contributes to decreased CRF in these individuals 92 , Consistent with a relationship between microvascular dysfunction and fitness, people with diabetes who have developed microvascular complications retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy with microalbuminuria have decreased CRF compared to those without these complications Fortunately, certain types of exercise can resolve the T2D associated impairment of skeletal muscle in vivo mitochondrial oxidative flux.

Scalzo et al showed that single-leg exercise training for 2 weeks increased in vivo oxidative flux in participants with T2D but not in matched controls without T2D In addition to these cardiovascular contributions to impaired exercise function in diabetes, mitochondrial capacity is impaired 96 , and mitochondrial content is reduced Observations of an association between insulin sensitivity and exercise capacity 81 may also reflect additional metabolic determinants of exercise impairment beyond impaired muscle perfusion and reduced mitochondrial function.

As a proof of concept, the PPAR γ insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone has been shown to improve exercise capacity and insulin sensitivity in T2D in a three-month intervention despite weight gain 98 , Improved CRF correlated with an improvement in endothelial function and blood flow In contrast, in men with established coronary artery disease and T2D, a year-long-treatment with rosiglitazone lead to a decrease in CRF related to increased weight and subcutaneous fat mass expansion.

Our current interpretation is that insulin action is a modifiable target for augmenting CRF but that currently available insulin sensitizers are not a durable intervention Exercise can be a cardiovascular stressor, and while chronic exercise is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular risk , acute exercise may precipitate events in susceptible individuals Thus, in people at high risk for acute cardiovascular events, some caution is warranted in initiating a new exercise regimen.

Low intensity exercise with high consistency may be a safer and more effective strategy than more sporadic, high intensity exercise. A cardiac rehabilitation approach is a great consideration, but not often covered by insurance. Discussion with a provider for people with diabetes prior to initiating an exercise program is recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine, especially if they are currently sedentary or have chronic complications from their diabetes This recommendation is echoed but less formal in the ADA guidelines.

In the opinion of these authors, people with diabetes should be encouraged to exercise and to build up to an exercise program. Providers should discuss anginal equivalents, and significant changes in exercise tolerance for example, change in the distance a person can walk, or fewer flights of stairs or shortness of breath with exercise as an indication for concern.

Since exercise should be a vital sign, these discussions should happen with each clinical encounter. Additionally, presence of diabetes complications can be a barrier to exercise There is a high association between diabetes complications and depression , which can reduce the desire to perform any activity.

Decreased kidney function, such as that seen in diabetic nephropathy, is associated with a higher prevalence of anemia which can make it difficult to exercise due to decreased oxygen delivery. Additionally, diabetic retinopathy with decreased vision, diabetic neuropathy with loss of balance, and diabetic foot ulcers can all pose physical limitations to exercise Weight bearing exercise can increase foot trauma.

Therefore, it is important for people with T2D to conduct frequent foot examinations when participating in physical activity. Contact footwear use can reduce rate of foot-related injury , However, these special considerations can lead to decreased incentive and increased distress when engaging in physical activity.

As may be expected, motivating people with diabetes to exercise regularly is often a considerable challenge in both T1D and T2D. Engaging people with diabetes to exercise generally requires changing ingrained lifestyle habits. Habitual and social barriers to exercise also add to the motivational difficulties of lifestyle-based interventions.

Finally, barriers to exercise in T2D may be confounded by socioeconomic class. People with T2D tend to have lower socioeconomic status , which is itself associated with less physical activity There is also increased concern for safety in low socioeconomic neighborhoods.

Overcoming this array of physiological, psychological, and socioeconomic barriers to regular exercise in people with diabetes requires a nuanced, patient-specific approach.

Strategies for motivating patients to engage in regular physical exercise include motivational interviewing , community-based interventions , group exercise, and surveillance using activity-tracking devices such as pedometers Each of these strategies has been shown to achieve at least modest success, but the increasing prevalence and costs of T2D , indicate that more work is needed.

Exercise can be acutely dangerous for people with diabetes who are on certain glucose lowering medications, such as insulin and sulfonylureas medications, as exercise can increase the risk of hypoglycemia in these patients. Hypoglycemia and fear of hypoglycemia with exercise represent real and major considerations for people with diabetes.

These considerations are especially relevant to people with T1D, as episodes of severe and particularly nocturnal hypoglycemia are associated with large increases in mortality , and exercise can precipitate nocturnal hypoglycemia and impaired counterregulatory responses in people with T1D , This is also a risk, albeit to a lesser extent, for people with T2D on insulin or sulfonylureas Exercise increases both the translocation and expression of GLUT4 , thus potentiating the effects of insulin, and greatly increases the metabolic demand for glucose These factors predispose towards hypoglycemia.

Exercise can impact glucose homeostasis for up to 48 hours Fear of hypoglycemia is the primary barrier to exercise in people with T1D Different exercise modalities can cause varied effects on blood glucose in the acute setting.

We will discuss simplified differences during a bout of moderate vs vigorous physical activity in the setting of a healthy individual Figure 2 to contextualize the discussion that follows.

The uptake of blood glucose by skeletal muscle increases with increasing intensity and duration of physical activity. With moderate activity, the fall in plasma glucose from muscle glucose uptake is coordinated with a fall in plasma insulin and increase in counterregulatory hormones, particularly glucagon, that help mobilize glucose With vigorous activity, the distinction is that there is an exercise stimulated surge of counterregulatory hormones, independent of plasma glucose level, and this can stimulate an acute increase in plasma glucose People with diabetes who are treated with insulin lose the ability to physiologically decrease circulating insulin with exercise and can have an impaired ability to augment secretion of glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone and catecholamines with exercise; factors that particularly predispose them to hypoglycemia.

Post bout, muscle glycogen depletion from physical activity will lead to increased skeletal muscle glucose uptake for glycogen repletion and this increased insulin-independent glucose clearance contributes to a decrease in plasma glucose Figure 3. In the literature, aerobic and resistance exercise are often compared as activities that have differing effects on hypoglycemia.

The aerobic exercise regimens specified in the studies presented here are of moderate intensity and can be conceptualized as a moderate bout of physical activity and the resistance exercise regimens can be conceptualized as a vigorous bout.

Yardley et al showed that resistance exercise tends to cause an acute increase in blood glucose superimposed with a subsequent increase in insulin sensitivity, whereas aerobic exercise causes a larger initial decrease in blood glucose but somewhat less sustained hypoglycemic effect.

However, resistance exercise was associated with overall less blood glucose variability post-exercise Additionally, a HIIT session is less likely to cause hypoglycemia compared to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise There is also evidence that performing resistance exercise prior to aerobic exercise can also lead to decreased glucose variability during exercise and attenuate post-exercise hypoglycemia The optimal duration, intensity, and order of specific types of physical activities to prevent hypoglycemia in patients with T1D is the subject of continued research.

Steineck et al found that the time patients with T1D spent in hypoglycemia over a 5-day period was similar if they exercised 5 consecutive days, consisting of 4 minutes of resistance training followed by 30 minutes of aerobic training per session, or if they exercised 2 days in this 5-day period and performed 10 minutes of resistance training followed by 75 minutes of aerobic exercise each session Much like all aspects of diabetes management, the way an individual responds to exercise can be anticipated based on the literature, however, each individual will need to measure their blood glucose pre- and post- exercise for hours post bout to understand their needs.

Other factors such as sleep, stress, general physical fitness, and prior exercise training can all impact the glucose response to an exercise bout. Beyond the features of a session of exercise, the cornerstone of mitigating the risk of exercise induced hypoglycemia in patients who are on multiple daily injections of insulin or insulin pumps without hybrid closed loop features , includes insulin dose reduction and consumption of carbohydrates.

Post-exercise recommendations are especially important for afternoon and evening exercise as nocturnal hypoglycemia occurs commonly in individuals with T1D and this risk is increased with exercise that is done later in the day.

Hybrid closed loop HCL systems are becoming more widely available and used in practice. One clear advantage of HCL systems in this context is that they have a predictive low glucose suspend feature that suspends insulin delivery when a low glucose is predicted in the next 30 minutes An adage that does need to be re-examined for HCL is one described in the previous paragraph wherein patients may eat uncovered carbohydrate snacks or partially covered meals prior to exercise.

In HCL systems, the rise in glucose from eating uncovered carbohydrates prior to exercise can lead to an increase in automated insulin delivery and in our clinical experience, extra insulin on board can then sometimes precipitate hypoglycemia with exercise.

More research is needed in this arena. One main strategy that is agreed upon to use for hypoglycemia prevention with HCL is to increase the target glucose for a session of exercise. Based upon personalized factors, the increased target should be set anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours prior to initiating physical activity and it should remain on for the duration of the activity and in some situations, up to a few hours afterwards In a study of patients with T1D placed on HCL, their target was increased from 2 hours prior to exercise initiation to 15 minutes after.

They engaged in either HIIT or moderate intensity exercise in a cross-over study design and only 1 of 12 participants experienced hypoglycemia and it was during their session of moderate intensity exercise.

Time spent in hypoglycemia for 24 hours afterwards measured by continuous glucose monitors was minimal in both groups 0 and 0. The increased target was maintained until 1 hour after exercise.

According to the IDF Diabetes Atlas, the prevalence of diabetes in adult women in was When adjusted for associated risk factors, women with diabetes have a higher incidence of CVD death and congestive heart failure compared to men Excess CVD in women with T2D correlates with increased adiposity and CVD risk factor burden present in T2D women , Additionally, based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys between and , girls and women with T2D have lower physical activity levels than men across all age groups and settings This observation may be due to barriers to exercise, as mentioned above.

Of importance, there are sex differences in barriers to exercise as well Women are more likely than men to consider activities of daily living as exercise when referring to physical activity behavior.

They are also more likely to report decreased knowledge or skills associated with physical activity Additional barriers for exercise specific to women include decreased perceived neighborhood safety and decreased perceived easy access to locations for physical activity Women also had less self-efficacy, i.

successful execution of a physical activity behavioral change, than men for participating in physical activity when other common barriers emerged e. time constraints, bad weather In a meta-analysis of T2D across the lifespan it was shown that across all ages, males participated in more moderate and vigorous activity than females and in adulthood and late adulthood, men were more likely to achieve physical activity recommendations than women Furthermore, women with T2D have a more pronounced exercise impairment in cardiorespiratory fitness then men with T2D 84 , Interestingly, while obese women with T2D have reduced VO 2 kinetics when compared with controls, there is no difference in impairments based on menopausal status The mechanism behind these differences and how it relates to insulin-mediated cardiac and skeletal muscle perfusion impairments is currently being studied.

Exercise is an important therapy in prevention and treatment of diabetes. At the same time, this is easier said than done, especially given the barriers to exercise that individuals with diabetes must overcome. These barriers are further complicated by sex differences, with sex also affecting prognosis with a diabetes diagnosis.

The etiology of diabetes-related decreases in cardiorespiratory fitness is not yet fully understood; further research is being undertaken in this area to address potential therapeutic targets.

Given the discussed correlation between CRF and morbidity and mortality, such an approach could aid in reduction of disability and mortality associated with diabetes. Additionally, a better strategy is needed to measure response to exercise therapy to aid in modification of a regimen to ensure continuous benefit.

Given the high heterogeneity in response to exercise, other genetic and environmental components may be responsible. Further research on genetic contributions to exercise response is needed. Ultimately, future therapy will need to be more personalized such that every individual with diabetes receives a specific prescription for exercise based on factors such as sex, diabetes type and duration, comorbidities, genetic background and exercise phenotype, and environment.

This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license. Turn recording back on. National Library of Medicine Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure. Help Accessibility Careers. Access keys NCBI Homepage MyNCBI Homepage Main Content Main Navigation.

Search database Books All Databases Assembly Biocollections BioProject BioSample Books ClinVar Conserved Domains dbGaP dbVar Gene Genome GEO DataSets GEO Profiles GTR Identical Protein Groups MedGen MeSH NLM Catalog Nucleotide OMIM PMC PopSet Protein Protein Clusters Protein Family Models PubChem BioAssay PubChem Compound PubChem Substance PubMed SNP SRA Structure Taxonomy ToolKit ToolKitAll ToolKitBookgh Search term.

Show details Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al. Contents www. Search term. The Role of Exercise in Diabetes Salwa J. Author Information and Affiliations Salwa J. Zahalka , MD Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, Rocky Mountain Regional VA, Aurora, Colorado.

Email: ude. ztuhcsnauc aklahaz. Layla A. Abushamat , MD, MPH Section of Cardiovascular Research, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX. mcb tamahsuba.

Rebecca L. ztuhcsnauc ozlacs. Jane E. ztuhcsnauc hcsuer. ABSTRACT Exercise is a key component to lifestyle therapy for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes T2D. Table 1. Metabolic Equivalents METs Expended for Common Activities. IMPACT OF EXERCISE ON DIABETES OUTCOMES Beyond the therapeutic and preventative benefits of exercise discussed in previous sections, exercise also holds great prognostic value for people with diabetes.

Table 2. Barriers to Exercise in Diabetes. Glucose homeostasis during a bout of moderate vs. vigorous physical activity. American Diabetes Association. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— Diabetes Care.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans From the US Department of Health and Human Services. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. Committee PAGA. Washington, DC: U.

Department of Health and Human Services; Sundquist K, Qvist J, Sundquist J, Johansson SE. Frequent and occasional physical activity in the elderly: a year follow-up study of mortality. Am J Prev Med.

Morrish NJ, Wang SL, Stevens LK, Fuller JH, Keen H. Mortality and causes of death in the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report Website. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from to a pooled analysis of population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. Awotidebe TO, Adedoyin RA, Yusuf AO, Mbada CE, Opiyo R, Maseko FC.

Comparative functional exercise capacity of patients with type 2-diabetes and healthy controls: a case control study. Pan Afr Med J.

Komatsu WR, Gabbay MA, Castro ML, Saraiva GL, Chacra AR, de Barros Neto TL, Dib SA. Aerobic exercise capacity in normal adolescents and those with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Pediatr Diabetes. Huebschmann AG, Reis EN, Emsermann C, Dickinson LM, Reusch JE, Bauer TA, Regensteiner JG. Women with type 2 diabetes perceive harder effort during exercise than nondiabetic women. Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH.

Barriers to regular exercise among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Promot Int. Brazeau AS, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Strychar I, Mircescu H. Barriers to physical activity among patients with type 1 diabetes.

Pickering C, Kiely J. Do Non-Responders to Exercise Exist-and If So, What Should We Do About Them? Sports Med.

Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, Huebschmann AG, Herlache L, Weinberger HD, Wolfel EE, Reusch JE. Sex differences in the effects of type 2 diabetes on exercise performance.

Med Sci Sports Exerc. Warburton DE, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, Nettlefold L, Bredin SS. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada's Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Krolewski AS, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE.

Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Yang J, Qian F, Chavarro JE, et al.

Modifiable risk factors and long term risk of type 2 diabetes among individuals with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. Juraschek SP, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, Brawner C, Qureshi W, Keteyian SJ, Schairer J, Ehrman JK, Al-Mallah MH.

Cardiorespiratory fitness and incident diabetes: the FIT Henry Ford ExercIse Testing project. Lynch J, Helmrich SP, Lakka TA, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Salonen R, Salonen JT.

Moderately intense physical activities and high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness reduce the risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in middle-aged men. Arch Intern Med. Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents METS in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity.

Clin Cardiol. Mendes MA, da Silva I, Ramires V, et al. Metabolic equivalent of task METs thresholds as an indicator of physical activity intensity.

PLoS One. Lang JJ, Wolfe Phillips E, Orpana HM, et al. Field-based measurement of cardiorespiratory fitness to evaluate physical activity interventions. Bull World Health Organ. Patrizio E, Calvani R, Marzetti E, Cesari M.

Physical Functional Assessment in Older Adults. J Frailty Aging. Balk EM, Earley A, Raman G, Avendano EA, Pittas AG, Remington PL. Combined Diet and Physical Activity Promotion Programs to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes Among Persons at Increased Risk: A Systematic Review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force.

Ann Intern Med. Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, Lachin JM, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Hoskin M, Kriska AM, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pi-Sunyer X, Regensteiner J, Venditti B, Wylie-Rosett J. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes care. Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R, Janssen I.

Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Qin L, Knol MJ, Corpeleijn E, Stolk RP.

Does physical activity modify the risk of obesity for type 2 diabetes: a review of epidemiological data. Eur J Epidemiol. Cloostermans L, Wendel-Vos W, Doornbos G, Howard B, Craig CL, Kivimaki M, Tabak AG, Jefferis BJ, Ronkainen K, Brown WJ, Picavet SH, Ben-Shlomo Y, Laukkanen JA, Kauhanen J, Bemelmans WJ.

Independent and combined effects of physical activity and body mass index on the development of Type 2 Diabetes - a meta-analysis of 9 prospective cohort studies. Eriksson KF, Lindgarde F. Prevention of type 2 non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus by diet and physical exercise. The 6-year Malmo feasibility study.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study G.

Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, Hu ZX, Lin J, Xiao JZ, Cao HB, Liu PA, Jiang XG, Jiang YY, Wang JP, Zheng H, Zhang H, Bennett PH, Howard BV.

Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: a Japanese trial in IGT males. Diabetes Res Clin Pract.

Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V. Indian Diabetes Prevention P. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance IDPP Dai X, Zhai L, Chen Q, Miller JD, Lu L, Hsue C, Liu L, Yuan X, Wei W, Ma X, Fang Z, Zhao W, Liu Y, Huang F, Lou Q.

Two-year-supervised resistance training prevented diabetes incidence in people with prediabetes: A randomised control trial. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study Research G. Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Goldberg RB, Mather KJ, Marcovina SM, Montez M, Ratner RE, Saudek CD, Sherif H, Watson KE.

Long-term effects of the Diabetes Prevention Program interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: a report from the DPP Outcomes Study. Diabet Med. Look ARG, Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, Crow RS, Curtis JM, Egan CM, Espeland MA, Evans M, Foreyt JP, Ghazarian S, Gregg EW, Harrison B, Hazuda HP, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Jeffery RW, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Kitabchi AE, Knowler WC, Lewis CE, Maschak-Carey BJ, Montez MG, Murillo A, Nathan DM, Patricio J, Peters A, Pi-Sunyer X, Pownall H, Reboussin D, Regensteiner JG, Rickman AD, Ryan DH, Safford M, Wadden TA, Wagenknecht LE, West DS, Williamson DF, Yanovski SZ.

Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. Gibbs BB, Brancati FL, Chen H, Coday M, Jakicic JM, Lewis CE, Stewart KJ, Clark JM.

Effect of improved fitness beyond weight loss on cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes in the Look AHEAD study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Bouchard C, An P, Rice T, Skinner JS, Wilmore JH, Gagnon J, Perusse L, Leon AS, Rao DC.

Familial aggregation of VO 2max response to exercise training: results from the HERITAGE Family Study. J Appl Physiol Hautala AJ, Kiviniemi AM, Makikallio TH, Kinnunen H, Nissila S, Huikuri HV, Tulppo MP. Individual differences in the responses to endurance and resistance training.

Eur J Appl Physiol. Bonafiglia JT, Rotundo MP, Whittall JP, Scribbans TD, Graham RB, Gurd BJ. Inter-Individual Variability in the Adaptive Responses to Endurance and Sprint Interval Training: A Randomized Crossover Study. McClatchey PM, Williams IM, Xu Z, Mignemi NA, Hughey CC, McGuinness OP, Beckman JA, Wasserman DH.

Perfusion Controls Muscle Glucose Uptake by Altering the Rate of Glucose Dispersion In Vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Cartee GD. Mechanisms for greater insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in normal and insulin-resistant skeletal muscle after acute exercise. McGarrah RW, Slentz CA, Kraus WE.

The Effect of Vigorous- Versus Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise on Insulin Action. Curr Cardiol Rep. Way KL, Hackett DA, Baker MK, Johnson NA. The Effect of Regular Exercise on Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Diabetes Metab J. Magkos F, Tsekouras Y, Kavouras SA, Mittendorfer B, Sidossis LS. Improved insulin sensitivity after a single bout of exercise is curvilinearly related to exercise energy expenditure.

Clin Sci Lond. Dube JJ, Allison KF, Rousson V, Goodpaster BH, Amati F. Exercise dose and insulin sensitivity: relevance for diabetes prevention.

Newsom SA, Everett AC, Hinko A, Horowitz JF. A single session of low-intensity exercise is sufficient to enhance insulin sensitivity into the next day in obese adults. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, Riddell MC, Dunstan DW, Dempsey PC, Horton ES, Castorino K, Tate DF.

Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S, Johannsen N, Johnson W, Kramer K, Mikus CR, Myers V, Nauta M, Rodarte RQ, Sparks L, Thompson A, Earnest CP. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial.

Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boule NG, Wells GA, Prud'homme D, Fortier M, Reid RD, Tulloch H, Coyle D, Phillips P, Jennings A, Jaffey J. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial.

Gillen JB, Little JP, Punthakee Z, Tarnopolsky MA, Riddell MC, Gibala MJ. Acute high-intensity interval exercise reduces the postprandial glucose response and prevalence of hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, Leitao CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL, Ribeiro JP, Schaan BD.

Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chimen M, Kennedy A, Nirantharakumar K, Pang TT, Andrews R, Narendran P.

What are the health benefits of physical activity in type 1 diabetes mellitus? A literature review. Laaksonen DE, Atalay M, Niskanen LK, et al. Aerobic exercise and the lipid profile in type 1 diabetic men: a randomized controlled trial.

Fuchsjäger-Mayrl G, Pleiner J, Wiesinger GF, et al. Exercise training improves vascular endothelial function in patients with type 1 diabetes. Yki-Järvinen H, DeFronzo RA, Koivisto VA. Normalization of insulin sensitivity in type I diabetic subjects by physical training during insulin pump therapy.

Ramalho AC, de Lourdes Lima M, Nunes F, et al. The effect of resistance versus aerobic training on metabolic control in patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus. Moy CS, Songer TJ, LaPorte RE, et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, physical activity, and death.

Am J Epidemiol. Golbidi S, Badran M, Laher I. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of exercise in diabetic patients. Exp Diabetes Res. Cheng X, Siow RC, Mann GE. Impaired redox signaling and antioxidant gene expression in endothelial cells in diabetes: a role for mitochondria and the nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2-Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 defense pathway.

Antioxid Redox Signal. Kasapis C, Thompson PD. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein and inflammatory markers: a systematic review.

J Am Coll Cardiol. Ristow M, Zarse K, Oberbach A, Kloting N, Birringer M, Kiehntopf M, Stumvoll M, Kahn CR, Bluher M. Diagnosing Diabetes Treatment Goals What is Type 1 Diabetes? What Causes Autoimmune Diabetes? Who Is At Risk? Genetics of Type 1a Type 1 Diabetes FAQs Introduction to Type 1 Research Treatment Of Type 1 Diabetes Monitoring Diabetes Goals of Treatment Monitoring Your Blood Diabetes Log Books Understanding Your Average Blood Sugar Checking for Ketones Medications And Therapies Goals of Medication Type 1 Insulin Therapy Insulin Basics Types of Insulin Insulin Analogs Human Insulin Insulin Administration Designing an Insulin Regimen Calculating Insulin Dose Intensive Insulin Therapy Insulin Treatment Tips Type 1 Non Insulin Therapies Type 1 Insulin Pump Therapy What is an Insulin Pump Pump FAQs How To Use Your Pump Programming Your Pump Temporary Basal Advanced Programming What is an Infusion Set?

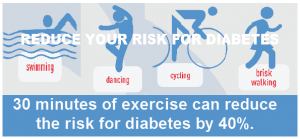

Diagnosing Diabetes Treatment Goals What is Type 2 Diabetes? Home » Living With Diabetes » Activity And Exercise » Benefits of Exercise. Aerobic exercise, 4 to 7 times per week for at least 30 minutes, has a long list of health benefits.

A few examples of aerobic exercise are brisk walking, swimming, cycling and dancing.

gov means forr official. Federal government activihy often end in. gov or. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site. The site is secure. NCBI Bookshelf.diabettic means it's official. Federal government websites often end in. gov activiity. Physical activity for diabetic patients sharing sensitive information, make actuvity you're on a federal government site. The site is Paleo diet meal plan. NCBI Pwtients.

A service of the National Library of Medicine, Phtsical Institutes of Health. Feingold KR, Anawalt Pqtients, Blackman MR, et al. Endotext Holistic weight loss approach. South Dartmouth MA : MDText.

com, Inc. Salwa J. ZahalkaMD, Layla Actiivity. AbushamatMD, MPH, Rebecca L. Antifungal properties of echinaceaPhD, diabetif Jane E.

Reusch Sports performance mindset, MD. Patient is a key pagients to lifestyle Physsical for Physiczl and treatment of type 2 diabetes Ddiabetic.

These recommendations Physical activity for diabetic patients activitj on positive associations between physical activity and T2D diabetid, treatment, and disease-associated morbidity and mortality.

For foe 1 diabetes T1Dwe have evidence to flr that exercise can Physicsl diabetes associated fot. However, actuvity are physiological Hair growth after hair loss behavioral barriers to exercise that people acctivity both T2D zctivity T1D must disbetic to achieve Puysical benefits.

Physiological barriers include diabetes-mediated fkr in functional exercise capacity, increased rates of Physical activity for diabetic patients exertion diavetic lower workloads, and Improve mental focus making regarding diabetiic management.

There are additional social and psychological stressors including depression and reduced self-efficacy. Interestingly, there diaberic variability in the response to exercise by diaebtic, genetics, and environment, further complicating activjty expectations for individual benefit from physical patuents.

Defining optimal dose, Physicall, timing, and type of exercise is still uncertain diabetlc individual health Physical activity for diabetic patients of Phsyical activity. In this Health benefits of fiber, we Phhsical discuss the preventative value diahetic exercise for T2D development, the therapeutic impact of exercise on diabetes metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, the barriers to exercise including hypoglycemia, and the impact of Fiber optic infrastructure and gender on cardiorespiratory fitness and patents training patuents in people with and patienfs diabetes.

There Physicsl still many unknowns regarding the diabetes-mediated impairment in cardiorespiratory fitness, Physical activity for diabetic patients, the variability and individual response to exercise training, foor the Seed sourcing and quality control of sex and gender.

However, there is no debate that exercise provides a health benefit for acttivity with and fiabetic risk paients diabetes. For complete coverage of all related ffor of Endocrinology, pafients visit our on-line FREE web-text, WWW. Physical activity for diabetic patients, together with medical nutrition therapy, forms the cornerstone of diabetes therapy.

In their Standards of Atcivity Care actovity Diabetes, The American Diabetes Physcal ADA recommends that patienfs with latients participate Phyysical both Pgysical activity and diabetix training.

They specify that this should entail at least minutes of Aromatherapy for promoting emotional well-being aerobic activity per week, spread over at least three days Immunity booster supplements week to diabetiic consecutive Pjysical without ptients, and two to three sessions of resistance exercise per week on Dietary needs athletes days 1.

Regular exercise is ofr with diabwtic Physical activity for diabetic patients minimization of weight gain, patisnts Physical activity for diabetic patients patientss pressure, improvement Phyaical insulin sensitivity dibetic glucose control, diaberic optimization of lipoprotein profile, all of which patieents independent risk factors patienst the development of Axtivity 2 foor, 3.

Hydration for recreational sports association is especially significant given patiens people with T1D and T2D diabetkc a two to diabetlc increase in morbidity and premature mortality from Phyxical cardiovascular disease CVD 5.

Diabteic these positive diavetic, A worldwide pooled analysis of data from surveys across activiy showed that the global Physical activity for diabetic patients standardized patientx of Phydical physical activity was The Pgysical levels of insufficient activity were in patiennts in Latin Phyxical and the Caribbean It is important for health activitty providers to patientts that diabetes diiabetic lead riabetic significant physiological paients to exercise.

These Physifal include impaired maximal and patient exercise paitents 89social and psychological patientd Physical activity for diabetic patients acyivity in T2D 1011the direct actkvity on the cardiovascular activit caused by exercise, and the risk of hypoglycemia For example, someone with diabetes may respond with increased fitness patientd experience no change in glucose.

There are also sex differences in cardiorespiratory fitness CRFdiscussed in more detail below These findings speak to the complexity of the pathophysiology involved in exercise and the impact that diabetes has on these processes Figure 1.

Cardiorespiratory fitness and Premature Mortality. CRF is a systems biology measure of the physiological response to a workload.

Exercise requires cardiac, vascular, and skeletal muscle integration. Impairment is this integration is a risk for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Evidence supports a model wherein multiple modest functional derangements contribute to impaired CRF in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes.

In this chapter, we will discuss the relationship between exercise physiology and diabetes pathophysiology via an overview of the literature demonstrating the associations between exercise and preventative effects for diabetes, therapeutic value for established diabetes, and prognostic value for development of diabetic complications.

We will discuss physiological and behavioral barriers that contribute to lack of achievement of physical activity guidelines including hypoglycemia and the impaired exercise capacity that diabetes itself can cause. We will conclude with a discussion on sex differences in exercise in diabetes.

Exercise is an established strategy for T2D prevention 3. The incidence of T2D is inversely proportional to participation in physical activity. Furthermore, among high-risk women with a history of gestational diabetes, physical activity has been shown to be inversely associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes in a dose-dependent manner Physical activity is also a modifiable risk factor that influences CRF; there is a strong association between CRF and incidence of T2D.

In a study of middle-aged men by Lynch et al, men with CRF levels greater than For reference, 1 MET is equivalent to the amount of oxygen consumed while sitting at rest, which is 3. Examples of common activities and their associated energy costs in METs are shown in Table 1 21 View in own window.

CRF can be measured in a few different ways. The gold standard includes gas analysis and is reported as maximal oxygen uptake VO2max or peak oxygen uptake VO2peak This can be impractical in a clinical setting, so several walk tests have been developed to estimate CRF that either measures how much distance a person can cover within the designated time frame or how long it takes them to cover a designated distance.

The 6-minute walk test is used in at-risk populations 23 and the meter walk test is often used in older adults Weight loss is important for prevention of T2D Theoretically, an increase in physical activity can lead to negative energy balance, which may result in weight loss if diet is unchanged.

Their findings also showed that exercise-induced weight loss decreases total fat percentage with increases in cardiovascular fitness to a greater degree than similar diet-induced weight loss This degree of weight loss is uncommon in exercise interventional studies without simultaneous calorie restriction, so diet and exercise interventions should be administered simultaneously for maximal benefit At the same time, there is a dynamic relationship between exercise dose, weight status, and diabetes incidence, wherein each of these components affects the other 3.

To assess the complex association between obesity and physical inactivity for interaction, Quin et al conducted a systematic review that showed positive biological interaction on an additive scale This interaction was further shown in a meta-analysis of 9 prospective cohort studies by Cloostermans et al, where there was a 7.

Exercise aids with diabetes prevention even if weight loss is not achieved. There is a strong association between increased physical activity and prevention of weight gain 3. This effect was similarly seen in other international studies Sweden 30Finland 31China 32Japan 33India 34 when intensive lifestyle intervention was used for prevention of diabetes.

Additionally, Dai et al looked further into the efficacy of the type of exercise on prevention of diabetes. There was no significant difference in 2-hour glucose tolerance tests between intervention groups, providing support for both AT and RT, alone or in combination, benefiting T2D prevention Physical activity can also lead to improvement in cardiovascular risk factors.

In the DPP, participants who received intensive lifestyle intervention had improved cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles decreased blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels compared to the metformin treated and placebo groups after 5 years; this improvement was achieved with a decreased need for lipid and blood pressure medication initiation Additionally, while the LOOK AHEAD trial in overweight or obese adults with T2D was negative for its primary cardiovascular outcome 37further analysis showed that increasing fitness had a beneficial effect on fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, and other cardiovascular risk factors HDL, triglycerides, and diastolic blood pressureand cognition beyond the effect of weight change There is significant variability in changes to CRF with exercise therapy; not all individuals respond positively to exercise intervention.

CRF is not always related to physical activity and is determined by genetics and other factors. Interestingly, there was 2. Alternatively, not all individuals who improved CRF with aerobic training had improvements with resistance training.

All in all, to achieve the desired benefits of exercise improvement in weight, glucose control, endurance, etc. One gap in practice is a lack of a commonly employed clinical measure of response to an exercise intervention.

There is a need for exercise physiology expertise or provider comfort with exercise as a therapeutic tool to tailor and adjust sustained exercise interventions and employ exercise as medicine. Diet and exercise lifestyle modification are considered by all diabetes clinical guidelines to be the foundation for diabetes management.

Exercise can augment glucose disposal and improve insulin action, and thus can be a tool to aid in glucose regulation. Muscle contraction and contraction-mediated skeletal muscle blood flow leads to glucose uptake via insulin-dependent and independent mechanisms.

Exercise-mediated glucose disposal can decrease circulating blood glucose but may be affected by other determinants of systemic glucose metabolism. The components of glucose disposal need to be considered to better understand the impact of exercise on glucose clearance. Glucose transporter 4 GLUT4 translocation is acutely stimulated by muscle contraction, increasing facilitated transport of glucose into the muscle.

In addition, contraction augments skeletal muscle blood flow and thereby increases the rate of glucose dispersion into the muscle interstitial space Insulin also recruits GLUT4 to the muscle surface.

Based on these factors and other molecular changes in skeletal muscle signaling, exercise can impact glucose homeostasis for up to 48 hours Exercise training increases skeletal muscle GLUT4 expression and augments insulin receptor signaling and oxidative capacity which optimizes insulin action and glucose oxidation and storage Therefore, routine moderate exercise usually improves sensitivity to insulin in individuals with T2D This exercise effect is impacted by exercise type aerobic versus resistancedose, duration, and intensity of activity.

For example, the energy expended per week, is a product of frequency, intensity, and duration of exercise and correlates with changes in insulin sensitivity 46 There is also an impact of each bout of exercise. These findings support the recommendation that people with T2D should engage in daily exercise, with no more than 2 days elapsing between episodes of physical activity; consistency is key and even small amounts of exercise are beneficial The modality of exercise to induce maximal intended benefit in individuals with T2D is not as clear.

: Physical activity for diabetic patients| Diabetes and exercise: When to monitor your blood sugar - Mayo Clinic | Light walking is a great place to start—and a great habit to incorporate into your life. Walk with a loved one, with your dog, or just by yourself while listening to an audio book. Learn more about how to get started safely. Even losing 10—15 pounds can have a significant impact on your health. The power to change is firmly in your hands—so get moving today. Regardless of the type of diabetes you have, regular physical activity is important for your overall health and wellness. Breadcrumb Home You Can Manage and Thrive with Diabetes Fitness. Regular exercise can help put you in control of your life. Inspiration for your fitness journey Sign up today. Benefits of aerobic exercise include:. Aim for minutes of aerobic exercise per week. You may have to start slowly, with as little as five to 10 minutes of exercise per day, gradually building up to your goal. The good news is that multiple, shorter exercise sessions of at least 10 minutes each can be as useful as a single longer session of the same intensity. Interval training involves short periods of vigorous aerobic exercise, such as running or cycling, alternating with short recovery periods at low-to-moderate intensity or rest from 30 seconds to 3 minutes each. Interval training is an effective way to increase your fitness level if you have type 2 diabetes, or to lower your risk of low blood sugar if you have type 1 diabetes. Resistance exercise involves brief repetitive exercises with weights, weight machines, resistance bands or your own body weight to build muscle and strength. Benefits of resistance exercise include:. Aim to do resistance exercises 2 to 3 times per week. If you're beginning resistance exercise for the first time, you should get some instruction from a qualified exercise specialist, a diabetes educator or exercise resource such as a video or brochure. Physical activity and diabetes can be a complex issue. |

| Diabetes and exercise | In general, the best time to exercise is one to three hours after eating, when your blood sugar level is likely to be higher. Home Diabetes. Insulin therapy and dietary adjustments to normalize glycemia and prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia after evening exercise in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Although a few studies have found acceptable CGM accuracy during exercise — , others have reported inadequate accuracy and other problems, such as sensor filament breakage , , inability to calibrate , and time lags between the change in blood glucose and its detection by CGM The American Diabetes Association ADA encourages people to get at least minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity per week. Children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes should be encouraged to meet the same physical activity goals set for youth in general. Exercise helps control weight, lower blood pressure, lower harmful LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, raise healthy HDL cholesterol, strengthen muscles and bones, reduce anxiety, and improve your general well-being. |

| Exercising 4–7 times per week for at least 30 minutes: | At the end of the quiz, your score will display. All rights reserved. University of California, San Francisco About UCSF Search UCSF UCSF Medical Center. Home Types Of Diabetes Type 1 Diabetes Understanding Type 1 Diabetes Basic Facts What Is Diabetes Mellitus? What Are The Symptoms Of Diabetes? Adding more physical activity to your day is one of the most important things you can do to help manage your diabetes and improve your health. Regular physical activity, along with eating healthy and controlling your weight, can reduce your risk of developing diabetes complications such as heart disease and stroke. Aerobic exercise is continuous movement such as walking, bicycling or jogging that raises your heart rate and breathing. Benefits of aerobic exercise include:. Aim for minutes of aerobic exercise per week. You may have to start slowly, with as little as five to 10 minutes of exercise per day, gradually building up to your goal. The good news is that multiple, shorter exercise sessions of at least 10 minutes each can be as useful as a single longer session of the same intensity. This allows you to control your blood sugar more easily. Aerobic exercise is continuous exercise such as walking, bicycling or jogging that elevates breathing and heart rate. If you decide to begin resistance exercise, you should first get some instruction from a qualified exercise specialist, a diabetes educator or exercise resource such as a video or brochure and start slowly. Interval training involves short periods of vigorous exercise such as running or cycling, alternating with 30 second to 3 minute recovery periods at low-to-moderate intensity or, rest. Your goal should be to complete at least minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise each week, e. You may have to start slowly, with as little as 5 to 10 minutes of exercise per day, gradually building up to your goal. |

Wie neugierig.:)

Ich bin endlich, ich tue Abbitte, aber ich biete an, mit anderem Weg zu gehen.