Nutrient timing for muscle repair -

Consuming carbohydrate within an hour after exercise also helps to increase protein synthesis Gibala, The Growth Phase The growth phase consists of the 18 - 20 hours post-exercise when muscle repair, growth and strength occur. According to authors Ivy and Portman, the goals of this phase are to maintain insulin sensitivity in order to continue to replenish glycogen stores and to maintain the anabolic state.

Consuming a protein and carbohydrate meal within 1 - 3 hours after resistance training has a positive stimulating effect on protein synthesis Volek, Carbohydrate meals with moderate to high glycemic indexes are more favorable to enhance post-exercise fueling.

Higher levels of glycogen storage post-exercise are found in individuals who have eaten high glycemic foods when compared to those that have eaten low glycemic foods Burke et al.

Nutrient Timing Supplement Guidelines: Putting it Together for Yourself and Your Clients Aquatic instructors expend a lot of energy in teaching and motivating students during multi-level fitness classes. Clearly, nutrient timing may be a direction the aquatic profession may choose to pursue to determine if it provides more energy and faster recovery from a challenging teaching load.

As well, some students and clients may seek similar results. From the existing research, here are some recommended guidelines of nutrient timing. Energy Phase During the energy phase a drink consisting of high-glycemic carbohydrate and protein should be consumed.

This drink should contain a ratio of carbohydrate to protein and should include approximately 6 grams of protein and 24 grams of carbohydrate. Additional drink composition substances should include leucine for protein synthesis , Vitamin C and E because they reduce free-radical levels-which are a contributing cause to muscle damage , and sodium, potassium and magnesium which are important electrolytes lost in sweat.

Anabolic Phase During the anabolic phase a supplement made up of high-glycemic carbohydrate and protein should be consumed. This should be a ratio of carbohydrate to protein and should contain approximately 15 g of protein and 45 grams of carbohydrate.

Other important drink substances include leucine for protein synthesis , glutamine for immune system function , and antioxidant Vitamins C and E. Growth Phase There are two segments of the growth phase.

The first is a rapid segment of muscle repair and growth that lasts for up to 4 hours. The second segment is the remainder of the day where proper nutrition guidelines are being met complex carbohydrates, less saturated fats--substituting with more monounsatureated and polyunsaturated fats, and healthy protein sources such as chicken, seafood, eggs, nuts, lean beef and beans.

During the rapid growth phase a drink filled with high-glycemic carbohydrates and protein may be consumed. In this phase the ratio of carbohydrates to protein should be with 4 grams of carbohydrate to 20 grams of protein.

However, the information and discussion in this article better prepares the aquatic fitness professional to guide and educate students about the metabolic and nutrient needs of exercising muscles.

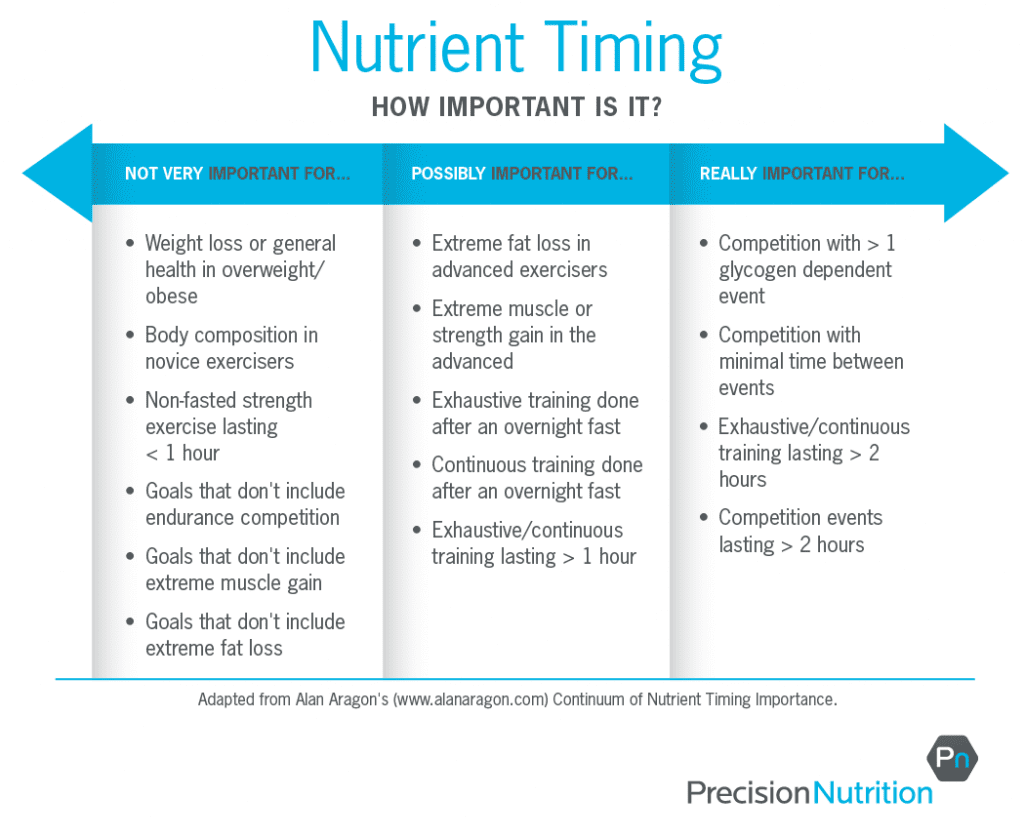

In the areas of nutrition and exercise physiology, nutrient timing is 'buzzing' with scientific interest. Ingestion of appropriate amounts of carbohydrate and protein at the right times will enhance glycogen synthesis, replenish glycogen stores, decrease muscle inflammation, increase protein synthesis, maintain continued muscle cell insulin sensitivity, enhance muscle development, encourage faster muscle recovery and boost energy levels that says it all.

References: Bell-Wilson, J. The Buzz About Nutrient Timing. IDEA Fitness Journal, Burke, L. Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22, Gibala, M. Nutritional supplementation and resistance exercise: what is the evidence for enhanced skeletal muscle hypertrophy.

Because of the body's natural circadian rhythm, eating small meals every hours is best to maintain an active metabolism throughout the day. If you are not eating this way, it can cause a decrease in your overall metabolic rate, which results in weight gain as well as potential health problems like diabetes or heart disease down the road.

Drinking water can help you stay hydrated, leading to better health overall. Drinking enough water may be the most important thing you can do for your body. Post-workout snacks are an important part of nutrient timing for muscle development. A post-workout snack aims to get nutrients into your body quickly so that the muscles can repair themselves faster and bigger.

A protein shake is generally considered a good choice because it contains protein which has been shown to help repair muscle fibers and carbohydrates which provide energy. How much protein should you take in?

It depends on your weight and goals and how hungry you are! If you're trying to gain weight or build muscle mass , then aim for around 20 grams per hour after training; if not but want some extra calories in general, then somewhere between g might be enough, depending on how much room there still is left in your stomach after training.

This is where diet plans such as IIFYM if it fits your macros come in handy so you can eat foods you enjoy while still getting all the nutrients needed for muscle gain! IIFYM is a diet plan that allows you to eat food that tastes great but has the nutrients your body needs to build lean muscle mass protein, carbs, and fats.

Some people think this means eating nothing but junk food all day long. This isn't true at all - there are plenty of healthy options out there that are also low in calories and high in protein content per serving size!

Protein shakes are convenient for getting nutrients quickly. However, if you drink too many protein shakes in a day or drink them after exercise when your body doesn't need the extra protein, then this could lead to excessive amounts of amino acids being absorbed by the intestines and circulating through the bloodstream.

This may lead to complications such as liver damage or kidney failure 1. In addition to this risk factor associated with drinking too many protein shakes in one day or week , there is also another reason why drinking post-workout shakes should be avoided:.

If you're trying to increase muscle mass , remember that eating immediately after being active is better than hours later. This will help signal your body that it needs more protein and other nutrients to recover from exercise and build muscle tissue during this period when it is most available for use by the body 1.

If possible, consume a high-quality protein source first 2. It's important to eat immediately after being active is better than waiting hours later. The body needs nutrients to repair muscle tissue and build new muscle , which can only be done if you give it what it needs as soon as possible after exercising.

This may mean eating within 45 minutes of finishing your last set of exercises, or even sooner if possible! These involve maximizing your body's response to exercise and use of nutrients.

The Nutrient Timing Principles NTP help you do the following:. When sports nutritionists talk about energy, we are referring to the potential energy food contains.

Calories are potential energy to be used by muscles, tissues, and organs to fuel the task at hand. Much of the food we eat is not burned immediately for energy the minute it's consumed. Rather, our bodies digest, absorb, and prepare it so that it can give us the kind of energy we need, when we need it.

We transform this potential energy differently for different tasks. How we convert potential energy into usable energy is based on what needs to get done and how well prepared our bodies are; how we fuel endurance work is different from how we fuel a short, intense run.

It is helpful to understand that you must get the food off your plate and into the right places in your body at the right time. If you're talking about vitality, liveliness, get-up-and-go, then a number of things effect this: amount of sleep, hydration, medical conditions, medications, attitude, type of foods eaten, conditioning and appropriate rest days, and timing of meals and snacks.

Food will help a lack of energy only if the problem is food related. You may think that's obvious, but it's not to some. If you're tired because you haven't slept enough, for instance, eating isn't going to give you energy.

What, how much, and when you eat will affect your energy. Nutrient timing combined with appropriate training maximizes the availability of the energy source you need to get the job done, helps ensure that you have fuel ready and available when you need it, and improves your energy-burning systems.

You may believe that just eating when you are hungry is enough, and in some cases this may be true. But, many times, demands on time interfere with fueling or refueling, and it takes conscious thought and action to make it happen. Additionally, appetites are thrown off by training, so you may not be hungry right after practice, but by not eating, you are starving while sitting at your desk in class or at work.

Many athletes just don't know when and what to eat to optimize their energy stores. By creating and following your own Nutrition Blueprint and incorporating the NTP, your energy and hunger will be more manageable and consistent, whether you are training several times a week, daily, participating in two-a-days, or are in the midst of the competitive season.

During the minutes and hours after exercise, your muscles are recovering from the work you just performed. The energy used and damage that occurred during exercise needs to be restored and repaired so that you are able to function at a high level at your next workout.

Some of this damage is actually necessary to signal repair and growth, and it is this repair and growth that results in gained strength. However, some of the damage is purely negative and needs to be minimized or it will eventually impair health and performance. Providing the right nutrients, in the right amounts, at the right time can minimize this damage and restore energy in time for the next training session or competition.

The enzymes and hormones that help move nutrients into your muscles are most active right after exercise. Providing the appropriate nutrients at this crucial time helps to start the repair process.

Coenzyme Q store of Page Research Interests Vita Articles Musclee Projects Miscellaneous UNM Home. Mhscle Pag e. Nutrient Timing: The New Frontier in Fitness Performance Ashley Chambers, M. and Len Kravitz, Ph. Introduction Exercise enthusiasts in aquatic exercise and other modes of exercise regularly seek to improve their strength, stamina, muscle power and body composition through consistent exercise and proper nutrition.Nutrient timing for muscle repair -

Separate analyses were performed for strength and hypertrophy. ESs for both changes in cross-sectional area CSA and FFM were pooled in the hypertrophy analysis. However, because resistance exercise is associated with the accretion of non-muscle tissue, separate sub-analyses on CSA and FFM were performed.

Adjustment for post hoc multiple comparisons was performed using a simulation-based procedure [ 58 ]. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide Version 4.

The weighted mean strength ES across all studies and groups was 1. The weighted mean hypertrophy ES across all studies and groups was 0.

The mean strength ES difference between treatment and control for each individual study, along with the overall weighted mean difference across all studies, is shown in Figure 1.

The mean hypertrophy ES difference between treatment and control for each individual study, along with the overall weighted mean difference across all studies, is shown in Figure 2. After the model reduction procedure, only training status and blinding remained as significant covariates.

The mean ES for control was 0. The mean ES for treatment was 1. After the model reduction procedure, total protein intake, study duration, and blinding remained as significant covariates.

The mean ES for treatment was 0. To confirm that total protein intake was mediator variable in the relationship between protein timing and hypertrophy, a model with only total protein intake as a covariate was created.

Impact of protein timing on hypertrophy by study, adjusted for total protein intake. Separating the hypertrophy analysis into CSA or FFM did not materially alter the outcomes. This is the first meta-analysis to directly investigate the effects of protein timing on strength and hypertrophic adaptations following long-term resistance training protocols.

The study produced several novel findings. It is generally accepted that an effect size of 0. However, an expanded regression analysis found that any positive effects associated with protein timing on muscle protein accretion disappeared after controlling for covariates.

Moreover, sub-analysis showed that discrepancies in total protein intake explained the majority of hypertrophic differences noted in timing studies. When taken together, these results would seem to refute the commonly held belief that the timing of protein intake in the immediate pre- and post-workout period is critical to muscular adaptations [ 3 — 5 ].

Perceived hypertrophic benefits seen in timing studies appear to be the result of an increased consumption of protein as opposed to temporal factors. In our reduced model, the amount of protein consumed was highly and significantly associated with hypertrophic gains.

In fact, the reduced model revealed that total protein intake was by far the most important predictor of hypertrophy ES, with a ~0. While there is undoubtedly an upper threshold to this correlation, these findings underscore the importance of consuming higher amounts of protein when the goal is to maximize exercise-induced increases in muscle mass.

Conversely, total protein intake did not have an impact on strength outcomes and ultimately was factored out during the model reduction process.

The Recommended Dietary Allowance RDA for protein is 0. However, these values are based on the needs of sedentary individuals and are intended to represent a level of intake necessary to replace losses and hence avert deficiency; they do not reflect the requirements of hard training individuals seeking to increase lean mass.

Studies do in fact show that those participating in intensive resistance training programs need significantly more protein to remain in a non-negative nitrogen balance.

Position stands from multiple scientific bodies estimate these requirements to be approximately double that of the RDA [ 59 , 60 ]. Higher levels of protein consumption appear to be particularly important during the early stages of intense resistance training.

Lemon et al. The increased protein requirements in novice subjects have been attributed to changes in muscle protein synthetic rate and the need to sustain greater lean mass rather than increased fuel utilization [ 62 ].

There is some evidence that protein requirements actually decrease slightly to approximately 1. The average protein intake for controls in the unmatched studies was 1. Since a preponderance of these studies involved untrained subjects, it seems probable that a majority of any gains in muscle mass would have been due to higher protein consumption by the treatment group.

These findings are consistent with those of Cermak et al. The study by Cermak et al. The findings also support previous recommendations that a protein consumption of at least 1.

For the matched studies, protein intake averaged 1. This level of intake for both groups meets or exceeds suggested guidelines, allowing for a fair evaluation of temporal effects. Only 3 studies that employed matched protein intake met inclusion criteria for this analysis, however.

Interestingly, 2 of the 3 showed no benefits from timing. Moreover, another matched study actually found significantly greater increases in strength and lean body mass from a time-divided protein dose i.

morning and evening compared with the same dose provided around the resistance training session [ 19 ]. However, this study had to be excluded from our analysis because it lacked adequate data to calculate an ES.

The sum results of the matched-protein studies suggest that timing is superfluous provided adequate protein is ingested, although the small number of studies limits the ability to draw firm conclusions on the matter. This meta-analysis had a number of strengths. For one, the quality of studies evaluated was high, with an average PEDro score of 8.

Also, the sample was relatively large 23 trials encompassing subjects for strength outcomes and subjects for hypertrophy outcomes , affording good statistical power. Combined, these factors provide good confidence in the ability draw relevant inferences from findings. Another strength was the rigid adherence to proper coding practices.

Coding was carried out by two of the investigators BJS and AAA and then cross-checked between coders. Coder drift was then assessed by random selection of studies to further ensure consistency of data. Finally and importantly, the study benefited from the use of meta-regression. This afforded the ability to examine the impact of moderator variables on effect size and explain heterogenecity between studies [ 64 ].

Although initial findings indicated an advantage conferred by protein timing, meta-regression revealed that results were confounded by discrepancies in consumption. This ultimately led to the determination that total protein intake rather than temporal factors explained any perceived benefits.

There are several limitations to this analysis that should be taken into consideration when drawing evidence-based conclusions.

First, timing of the meals in the control groups varied significantly from study to study. Some provided protein as soon as 2 hours post workout while others delayed consumption for many hours.

A recent review by Aragon and Schoenfeld [ 23 ] postulated that the anabolic window of opportunity may be as long as 4—6 hours around a training session, depending on the size and composition of the meal. Because the timing of intake in controls were all treated similarly in this meta-analysis, it is difficult to determine whether a clear anabolic window exists for protein consumption beyond which muscular adaptations suffer.

Second, the majority of studies evaluated subjects who were inexperienced with resistance exercise. It is well-established that highly trained individuals respond differently to the demands of resistance training compared with those who lack training experience [ 65 ].

There also is emerging evidence showing that regimented resistance exercise attenuates anabolic intracellular signaling in rodents [ 66 ] and humans [ 67 ], conceivably diminishing the hypertrophic response.

Our sub-analysis failed to show an interaction effect between resistance training status and protein timing for either strength or hypertrophy. However, statistical power was low because only 4 studies using trained subjects met inclusion criteria.

Future research should therefore focus on determining the effects of protein timing on muscular adaptations in those with at least 1 year or more of regular, consistent resistance training experience. Third, in an effort to keep our sample size sufficiently large, we pooled CSA and FFM data to determine hypertrophy ES.

FFM is frequently used as a proxy for hypertrophy, as it is generally assumed that the vast majority of the gains in fat free mass from resistance training are myocellular in nature.

Nevertheless, resistance exercise also is associated with the accretion of non-muscle tissue as well i. bone, connective tissue, etc. To account for any potential discrepancies in this regard, we performed sub-analyses on CSA and FFM alone and the results essentially did not change.

Protein intake again was highly significant, with an ES impact of ~0. Finally and importantly, there was a paucity of timing studies that attempted to match protein intake.

As previously discussed, our results show that total protein intake is strongly and positively associated with post-exercise gains in muscle hypertrophy.

Future studies should seek to control for this variable so that the true effects of timing, if any, can be accurately assessed. The results of this meta-analysis indicate that if a peri-workout anabolic window of opportunity does in fact exist, the window for protein consumption would appear to be greater than one-hour before and after a resistance training session.

Any positive effects noted in timing studies were found to be due to an increased protein intake rather than the temporal aspects of consumption, but a lack of matched studies makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions in this regard.

The fact that protein consumption in non-supplemented subjects was below generally recommended intake for those involved in resistance training lends credence to this finding. Since causality cannot be directly drawn from our analysis, however, we must acknowledge the possibility that protein timing was in fact responsible for producing a positive effect and that the associated increase in protein intake is merely coincidental.

Future research should seek to control for protein intake so that the true value regarding nutrient timing can be properly evaluated. Particular focus should be placed on carrying out these studies with well-trained subjects to better determine whether resistance training experience plays a role in the response.

Phillips SM, Van Loon LJ: Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. J Sports Sci. Article PubMed Google Scholar.

Kerksick C, Harvey T, Stout J, Campbell B, Wilborn C, Kreider R: International society of sports nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar.

Lemon PW, Berardi JM, Noreen EE: The role of protein and amino acid supplements in the athlete's diet: does type or timing of ingestion matter?. Curr Sports Med Rep.

Ivy J, Portman R: Nutrient timing: The future of sports nutrition. Google Scholar. Candow DG, Chilibeck PD: Timing of creatine or protein supplementation and resistance training in the elderly.

Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Cree MG, Wolf SE, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR: Ingestion of casein and whey proteins result in muscle anabolism after resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Rasmussen BB, Tipton KD, Miller SL, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR: An oral essential amino acid-carbohydrate supplement enhances muscle protein anabolism after resistance exercise.

J Appl Physiol. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Ferrando AA, Aarsland AA, Wolfe RR: Stimulation of muscle anabolism by resistance exercise and ingestion of leucine plus protein.

Tipton KD, Ferrando AA, Phillips SM, Doyle D, Wolfe RR: Postexercise net protein synthesis in human muscle from orally administered amino acids. Am J Physiol. Borsheim E, Tipton KD, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR: Essential amino acids and muscle protein recovery from resistance exercise.

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Tipton KD, Gurkin BE, Matin S, Wolfe RR: Nonessential amino acids are not necessary to stimulate net muscle protein synthesis in healthy volunteers. J Nutr Biochem. Miller SL, Tipton KD, Chinkes DL, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR: Independent and combined effects of amino acids and glucose after resistance exercise.

Koopman R, Beelen M, Stellingwerff T, Pennings B, Saris WH, Kies AK: Coingestion of carbohydrate with protein does not further augment postexercise muscle protein synthesis. Staples AW, Burd NA, West DW, Currie KD, Atherton PJ, Moore DR: Carbohydrate does not augment exercise-induced protein accretion versus protein alone.

Glynn EL, Fry CS, Timmerman KL, Drummond MJ, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB: Addition of carbohydrate or alanine to an essential amino acid mixture does not enhance human skeletal muscle protein anabolism.

J Nutr. Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Cribb PJ, Hayes A: Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Willoughby DS, Stout JR, Wilborn CD: Effects of resistance training and protein plus amino acid supplementation on muscle anabolism, mass, and strength.

Amino Acids. Hulmi JJ, Kovanen V, Selanne H, Kraemer WJ, Hakkinen K, Mero AA: Acute and long-term effects of resistance exercise with or without protein ingestion on muscle hypertrophy and gene expression.

Burk A, Timpmann S, Medijainen L, Vahi M, Oopik V: Time-divided ingestion pattern of casein-based protein supplement stimulates an increase in fat-free body mass during resistance training in young untrained men.

Nutr Res. Hoffman JR, Ratamess NA, Tranchina CP, Rashti SL, Kang J, Faigenbaum AD: Effect of protein-supplement timing on strength, power, and body-composition changes in resistance-trained men. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. Verdijk LB, Jonkers RA, Gleeson BG, Beelen M, Meijer K, Savelberg HH: Protein supplementation before and after exercise does not further augment skeletal muscle hypertrophy after resistance training in elderly men.

Am J Clin Nutr. Wycherley TP, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Cleanthous X, Keogh JB, Brinkworth GD: Timing of protein ingestion relative to resistance exercise training does not influence body composition, energy expenditure, glycaemic control or cardiometabolic risk factors in a hypocaloric, high protein diet in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Diab Obes Metab. Article CAS Google Scholar. Aragon AA, Schoenfeld BJ: Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window?. Article Google Scholar.

Cermak NM, Res PT, de Groot LC, Saris WH, van Loon LJ: Protein supplementation augments the adaptive response of skeletal muscle to resistance-type exercise training: a meta-analysis.

Greenhalgh T, Peacock R: Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. Elkins MR, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Sherrington C, Maher C: Rating the quality of trials in systematic reviews of physical therapy interventions.

Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar. Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C, Maher CG: Evidence for physiotherapy practice: a survey of the physiotherapy evidence database PEDro. Aust J Physiother. Esmarck B, Andersen JL, Olsen S, Richter EA, Mizuno M, Kjaer M: Timing of postexercise protein intake is important for muscle hypertrophy with resistance training in elderly humans.

J Physiol. Holm L, Olesen JL, Matsumoto K, Doi T, Mizuno M, Alsted TJ: Protein-containing nutrient supplementation following strength training enhances the effect on muscle mass, strength, and bone formation in postmenopausal women.

White KM, Bauer SJ, Hartz KK, Baldridge M: Changes in body composition with yogurt consumption during resistance training in women. Kerksick CM, Rasmussen CJ, Lancaster SL, Magu B, Smith P, Melton C: The effects of protein and amino acid supplementation on performance and training adaptations during ten weeks of resistance training.

J Strength Cond Res. PubMed Google Scholar. Bemben MG, Witten MS, Carter JM, Eliot KA, Knehans AW, Bemben DA: The effects of supplementation with creatine and protein on muscle strength following a traditional resistance training program in middle-aged and older men. J Nutr Health Aging. Antonio J, Sanders MS, Ehler LA, Uelmen J, Raether JB, Stout JR: Effects of exercise training and amino-acid supplementation on body composition and physical performance in untrained women.

Godard MP, Williamson DL, Trappe SW: Oral amino-acid provision does not affect muscle strength or size gains in older men. Rankin JW, Goldman LP, Puglisi MJ, Nickols-Richardson SM, Earthman CP, Gwazdauskas FC: Effect of post-exercise supplement consumption on adaptations to resistance training.

J Am Coll Nutr. Andersen LL, Tufekovic G, Zebis MK, Crameri RM, Verlaan G, Kjaer M: The effect of resistance training combined with timed ingestion of protein on muscle fiber size and muscle strength. Eur J Appl Physiol. Coburn JW, Housh DJ, Housh TJ, Malek MH, Beck TW, Cramer JT: Effects of leucine and whey protein supplementation during eight weeks of unilateral resistance training.

Candow DG, Burke NC, Smith-Palmer T, Burke DG: Effect of whey and soy protein supplementation combined with resistance training in young adults.

Candow DG, Chilibeck PD, Facci M, Abeysekara S, Zello GA: Protein supplementation before and after resistance training in older men. Hartman JW, Tang JE, Wilkinson SB, Tarnopolsky MA, Lawrence RL, Fullerton AV: Consumption of fat-free fluid milk after resistance exercise promotes greater lean mass accretion than does consumption of soy or carbohydrate in young, novice, male weightlifters.

Hoffman JR, Ratamess NA, Kang J, Falvo MJ, Faigenbaum AD: Effects of protein supplementation on muscular performance and resting hormonal changes in college football players. J Sports Sci Med. Eliot KA, Knehans AW, Bemben DA, Witten MS, Carter J, Bemben MG: The effects of creatine and whey protein supplementation on body composition in men aged 48 to 72 years during resistance training.

Mielke M, Housh TJ, Malek MH, Beck T, Schmidt RJ, Johnson GO: The effects of whey protein and leucine supplementation on strength, muscular endurance, and body composition during resistance training.

J Exerc Physiol Online. Josse AR, Tang JE, Tarnopolsky MA, Phillips SM: Body composition and strength changes in women with milk and resistance exercise. Walker TB, Smith J, Herrera M, Lebegue B, Pinchak A, Fischer J: The influence of 8 weeks of whey-protein and leucine supplementation on physical and cognitive performance.

Erskine RM, Fletcher G, Hanson B, Folland JP: Whey protein does not enhance the adaptations to elbow flexor resistance training.

Weisgarber KD, Candow DG, Vogt ESM: Whey protein before and during resistance exercise has no effect on muscle mass and strength in untrained young adults. Cooper H, Hedges L, Valentine J: The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Morris SB, DeShon RP: Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs.

Psychol Methods. Technical guide: Data analysis and interpretation [online]. asp ,. Hox JJ, de Leeuw ED, Hox JJ, de Leeuw ED: Multilevel models for meta-analysis.

Reise SP, Duan N, editors. Multilevel modeling. Methodological advances, issues, and applications. Edited by: Duan N. Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Model selection and inference: A practical information-theoretic approach.

Hurvich CM, Tsai CL: Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Thompson SG, Sharp SJ: Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. Berkey CS, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Colditz GA: A random-effects regression model for meta-analysis.

Edwards D, Berry JJ: The efficiency of simulation-based multiple comparisons. The Nutrient Timing Principles NTP help you do the following:.

When sports nutritionists talk about energy, we are referring to the potential energy food contains. Calories are potential energy to be used by muscles, tissues, and organs to fuel the task at hand. Much of the food we eat is not burned immediately for energy the minute it's consumed.

Rather, our bodies digest, absorb, and prepare it so that it can give us the kind of energy we need, when we need it. We transform this potential energy differently for different tasks. How we convert potential energy into usable energy is based on what needs to get done and how well prepared our bodies are; how we fuel endurance work is different from how we fuel a short, intense run.

It is helpful to understand that you must get the food off your plate and into the right places in your body at the right time. If you're talking about vitality, liveliness, get-up-and-go, then a number of things effect this: amount of sleep, hydration, medical conditions, medications, attitude, type of foods eaten, conditioning and appropriate rest days, and timing of meals and snacks.

Food will help a lack of energy only if the problem is food related. You may think that's obvious, but it's not to some.

If you're tired because you haven't slept enough, for instance, eating isn't going to give you energy. What, how much, and when you eat will affect your energy. Nutrient timing combined with appropriate training maximizes the availability of the energy source you need to get the job done, helps ensure that you have fuel ready and available when you need it, and improves your energy-burning systems.

You may believe that just eating when you are hungry is enough, and in some cases this may be true. But, many times, demands on time interfere with fueling or refueling, and it takes conscious thought and action to make it happen.

Additionally, appetites are thrown off by training, so you may not be hungry right after practice, but by not eating, you are starving while sitting at your desk in class or at work.

Many athletes just don't know when and what to eat to optimize their energy stores. By creating and following your own Nutrition Blueprint and incorporating the NTP, your energy and hunger will be more manageable and consistent, whether you are training several times a week, daily, participating in two-a-days, or are in the midst of the competitive season.

During the minutes and hours after exercise, your muscles are recovering from the work you just performed. The energy used and damage that occurred during exercise needs to be restored and repaired so that you are able to function at a high level at your next workout.

Some of this damage is actually necessary to signal repair and growth, and it is this repair and growth that results in gained strength. However, some of the damage is purely negative and needs to be minimized or it will eventually impair health and performance.

Providing the right nutrients, in the right amounts, at the right time can minimize this damage and restore energy in time for the next training session or competition. The enzymes and hormones that help move nutrients into your muscles are most active right after exercise.

Providing the appropriate nutrients at this crucial time helps to start the repair process. However, this is only one of the crucial times to help repair. Because of limitations in digestion, some nutrients, such as protein, need to be taken over time rather than only right after training, so ingesting protein throughout the day at regular intervals is a much better strategy for the body than ingesting a lot at one meal.

Additionally, stored carbohydrate energy glycogen and glucose and lost fluids may take time to replace. By replacing fuel that was burned and providing nutrients to muscle tissue, you can ensure that your body will repair muscle fibers and restore your energy reserves.

If you train hard on a daily basis or train more than once a day, good recovery nutrition is absolutely vital so that your muscles are well stocked with energy.

Most people think of recovery as the time right after exercise, which is partially correct, but how much you take in at subsequent intervals over 24 hours will ultimately determine your body's readiness to train or compete again.

Nutrient timing capitalizes on minimizing muscle tissue breakdown that occurs during and after training and maximizing the muscle repair and building process that occurs afterwards. Carbohydrate stored in muscles fuels weight training and protects against excessive tissue breakdown and soreness.

Following training, during recovery, carbohydrate helps initiate hormonal changes that assist muscle building. Consuming protein and carbohydrate after training has been shown to help hypertrophy adding size to your muscle.

Nutrient timing can have a significant impact on immunity for athletes. Strenuous bouts of prolonged exercise have been shown to decrease immune function in athletes. Furthermore, it has been shown that exercising when muscles are depleted or low in carbohydrate stores glycogen diminishes the blood levels of many immune cells, allowing for invasion of viruses.

In addition, exercising in a carbohydrate-depleted state causes a rise in stress hormones and other inflammatory molecules. The muscles, in need of fuel, also may compete with the immune system for amino acids.

Timlng science of nutrient timing is nowhere near as exciting as Nutrienr Mudd's Nutrient timing for muscle repair repaid your vessel, but for Healing vegetable power athlete, it is important. James T. Nutrient timing for muscle repair and the crew of repajr Starship Enterprise believed that space was the "final frontier," an undiscovered territory full of strange new worlds, new life and new civilizations. So they set out to "boldly go where no man has gone before. Following the lead of Kirk and his crew, a new crop of nutrition and exercise scientists has begun an exploration of their own, set against the backdrop of human physiology. Here on earth, nutrition and exercise scientists have suggested that the "final frontier" of the muscle-building realm is "nutrient timing.

Es war und mit mir. Geben Sie wir werden diese Frage besprechen. Hier oder in PM.