Video

Twin Flames Universe: A Dangerous \u0026 Deadly Obsession?Gut health and nutrient timing -

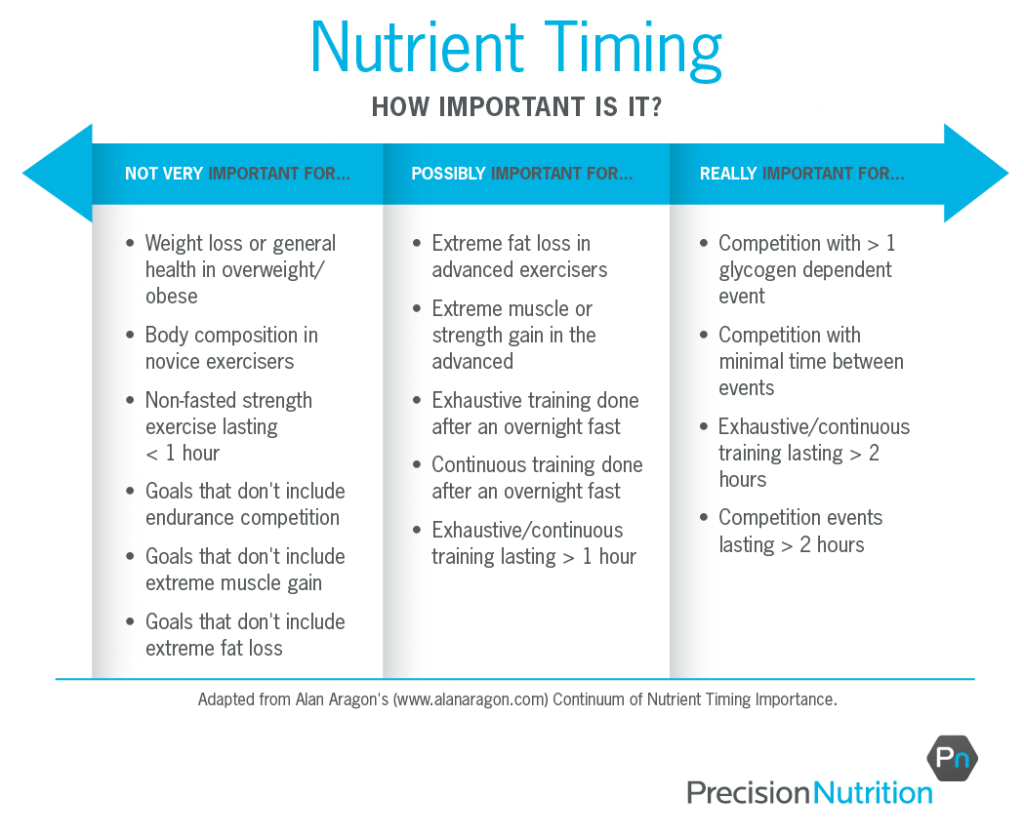

Additionally, vitamins may affect workout performance, and may even reduce training benefits. So although vitamins are important nutrients, it may be best not to take them close to your workout Nutrient timing may play an important role in pre-workout nutrition, especially if you want to maximize performance, improve body composition or have specific health goals.

Instead, what you eat for breakfast has become the hot topic. Many professionals now recommend a low-carb, high-fat breakfast, which is claimed to improve energy levels, mental function, fat burning and keep you full. However, while this sounds great in theory, most of these observations are anecdotal and unsupported by research Additionally, some studies show that protein-based breakfasts have health benefits.

However, this is likely due to the many benefits of protein, and timing probably does not play a role Your breakfast choice should simply reflect your daily dietary preferences and goals. There is no evidence to support one best approach for breakfast.

Your breakfast should reflect your dietary preferences and goals. This reduction of carbs simply helps you reduce total daily calorie intake, creating a calorie deficit — the key factor in weight loss. The timing is not important. In contrast to eliminating carbs at night, some research actually shows carbs can help with sleep and relaxation, although more research is needed on this This may hold some truth, as carbs release the neurotransmitter serotonin, which helps regulate your sleep cycle.

Cutting carbs at night is not a good tip for losing weight, especially since carbs may help promote sleep. However, further research is needed on this. Instead, focus your efforts on consistency, daily calorie intake, food quality and sustainability.

Whether your diet is high or low in carbs, you may wonder if timing matters to reap their benefits. This article discusses whether there is a best…. While they're not typically able to prescribe, nutritionists can still benefits your overall health. Let's look at benefits, limitations, and more.

A new study found that healthy lifestyle choices — including being physically active, eating well, avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol consumption —…. Carb counting is complicated. Take the quiz and test your knowledge!

Together with her husband, Kansas City Chiefs MVP quarterback Patrick Mahomes, Brittany Mohomes shares how she parents two children with severe food…. While there are many FDA-approved emulsifiers, European associations have marked them as being of possible concern.

Let's look deeper:. Researchers have found that a daily multivitamin supplement was linked with slowed cognitive aging and improved memory. Dietitians can help you create a more balanced diet or a specialized one for a variety of conditions. We look at their benefits and limitations.

Liquid collagen supplements might be able to reduce some effects of aging, but research is ongoing and and there may be side effects. Protein powders are popular supplements that come from a variety of animal- and plant-based sources. This article discusses whether protein powders….

A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Total stool output i. Participants lost on average 5. dinner 5. Similarly, the time of main meal consumption did not significantly associate with fecal energy output or content Table 1. Regardless of the way data were expressed, fecal SCFA were not significantly different between the 2 interventions Table 2.

The last sample provided by each participant and for each intervention was sequenced using the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Using either the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity Fig.

material 3. There was no deviation of any participants from their enterotype, suggesting that the effect of meal timing was unable to supersede the effect of enterotypes. In differential analysis, the taxon relative abundance of 8 OTUs and 7 genera differed between the 2 interventions Fig.

However, these significant effects vanished when analysis was corrected for multiple testing. Otherwise, the microbiome profile remained unaffected between the 2 dietary interventions at OTU Fig.

material 4. Effect of timing of main meal consumption on the gut microbiome of healthy volunteers. a NMDS using Bray-Curtis distances of OTU community structure. b NMDS using weighted Unifrac distance analysis.

c Rarefied richness. d Chao1 index. e Exponential of Shannon index eH. NMDS, nonmetric multidimensional scaling; OTU, operational taxonomic unit. Log-relative abundance significant differences between the 2 dietary interventions.

a OTU level. b Genus level. OTU, operational taxonomic unit. Effect of the timing of main meal consumption on the relative abundance of the top 20 common OTUs group mean.

Mean microbiome profile of all participants per dietary intervention. A1—A17, microbiome profile of each participant per dietary intervention; OTU, operational taxonomic units.

The time of main meal consumption did not influence significantly the fecal concentration of total bacteria or other bacterial groups except for E. coli , which was significantly higher after the large lunch intervention. This effect remained significant regardless of the approach used to express the data Table 3.

Effect of timing of main meal consumption on blood biomarkers of cardiometabolic health. Box plots show means and quartiles. TAG, triglycerides; CRP, C-reactive protein.

White boxplot indicates the large dinner intervention, and gray boxplot indicates the large lunch intervention.

One participant had a raised CRP after the end of the second intervention due to a recent cold. Repetition of statistical analysis after exclusion of this participant did not change the difference in the mean effects observed between the 2 interventions.

This study was set out to investigate the effect of the time of main meal consumption on the gastrointestinal microbiome and cardiometabolic factors of the host. Against our hypothesis, we found that the time at which the main meal was consumed had no acute effects on fecal pH, form and texture of feces, fecal water content, total energy loss in feces, total fecal SCFA output, and the global microbial community structure or taxon relative abundance inferred using high-throughput sequencing.

When we looked at the effect of the 2 interventions on the absolute concentration of dominant bacterial species, we observed a significant increase in the absolute concentration of E. coli after consumption of the main meal as lunch.

This effect is unlikely to be a random or spurious finding as it persisted when we expressed the amount of this species as the average concentration of all samples per participant, concentration, or total output over 3-day complete fecal sample collection.

Interestingly, this signal was not replicated using high-throughput sequencing most likely due to different expression of data absolute vs.

relative abundance and other counterbalancing changes. With the exception of the significant effect of our intervention on E. coli , these findings are against our hypothesis and those results presented previously in cross-sectional research [ 5 ].

It could be postulated that the E. Kaczmarek et al. Another study investigating the effects of the Western diet on the gastrointestinal microbiome of mice found that it caused an increase in fecal E.

coli levels [ 15 ]. It is therefore possible that a similar response to the Western diet occurred in our participants. Diet has been previously shown to influence fecal SCFA content [ 16 ], but evidence implicating main meal timing is scarce.

We found no significant differences between the lunch and dinner meal interventions for any of the 10 SCFA tested. This observation agrees with previous cross-sectional research in which eating behavior i. Similarly, we found no difference between the 2 interventions on blood biomarkers of CVD risk.

This means that the time at which the main meal was consumed had no acute effects on blood CVD biomarkers such as blood lipids, insulin resistance, or low-grade inflammation, despite weight gain following the intervention with large dinner.

Supporting the findings from this study, a recent weight loss study comparing the effects of a large lunch with a large dinner [ 9 ] found that although a decrease in blood lipids was noted for both groups and in parallel to their weight loss, the change in blood lipid level was not significantly different between the 2 interventions.

Similarly, a crossover RCT investigating snacking times 10 a. found that time of consumption of a high-fat, high-carbohydrate snack had no significant effects on serum triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, but late snacking produced a significant increase in total and LDL cholesterol [ 17 ].

Neither fasted blood insulin, glucose, nor HOMA-IR was responsive to different timing of the main meal. These findings are supported by previous research and a recent meta-analysis where snacking time had no effect on HOMA-IR, insulin, or glucose levels [ 17, 18 ].

Contrary to this evidence, when meal times were delayed by 5 h, plasma glucose rhythms were also delayed by approximately 5 h and average glucose concentration decreased [ 19 ]. Madjd et al. This result was, however, dependent on weight loss, which in the current study was not observed in the intervention with lunch as the main meal, and although weight gain was observed in the other group, the magnitude of this effect was very modest and perhaps too small to evoke an acute effect in young otherwise healthy subjects.

Two proinflammatory cytokines and CRP were measured here as markers of low-grade systemic inflammation, particularly as these markers are often elevated in obese individuals [ 20 ]. Although the origin of this low-grade inflammation remains unknown, there is accumulating evidence to suggest that this might be due to the effect of diet on the gut microbiome and associated endotoxemia [ 2 ].

Our results suggest that time of main meal consumption is unlikely to be a contributor to low-grade inflammation, and this effect is unlikely to be associated with changes in the gut microbiome. Bomb calorimetry was used on all stool samples from all participants to estimate intestinal absorption capacity [ 21 ] and the effect of the 2 interventions on the percentage of fecal water content and the Bristol Stool Scale as proxies of gastrointestinal motility.

Nutrient load has previously been shown to be associated with changes to the microbiome and correlating with changes to energy loss in stool [ 22 ]. Nonetheless, this RCT is the first of its kind to investigate the associations between time of food consumption, energy content of stool, and microbiome changes and found no statistically significant association between time of main meal and cumulative energy content of fecal samples.

Average fecal energy content met expected healthy values for both interventions [ 23 ]. This well-controlled study is not without its limitations. The study is of modest sample size, but the size effect and associated p values observed suggest that this study is unlikely to suffer from loss of statistical power.

Recruitment of more participants is unlikely to have altered the primary findings presented; therefore, extension of recruitment was deemed unnecessary.

It is however possible that the discordant results for E. We are also unable to comment on long-term effects that meal timing may have on the gut microbiome and cardiometabolic factors. With this in mind, the current study has several strengths. A robust study design was employed, with each participant acting as their own control.

Furthermore, each participant had a personalized diet which equated their energy requirements and was based on their food preferences, and meals were provided to maximize compliance and accurate dietary intake assessment. This hypothesis testing study investigating the effects of the time of main meal consumption on the microbiome and the host found that main meal timing had minimal acute effects on cardiometabolic factors in the blood, intestinal absorption capacity, or on microbiome composition or activity.

It is therefore unlikely that either a large lunch or a large dinner affects the diurnal rhythms of the gut microbiota and, by proxy, the onset of noncommunicable diseases influenced by the latter. In a presumptive causal pathway between timing of meal and risk of CVD onset, the gut microbiota is likely not to be implicated, at least in the short term.

Future investigations should look to expand upon the findings of this study with longer duration of dietary interventions. The study received approval by the MLVS Research Ethics Committee at the University of Glasgow Reference number: Miss Katrina Ballantyne received a summer undergraduate student bursary by the Rank Prize Funds.

conducted the clinical aspects of the research and data collection; R. conducted the laboratory analysis of samples; B. performed the statistical analysis of the data and microbiome bioinformatics; K.

designed and supervised the research, wrote the paper with the support of R. and D. Although our findings need to be confirmed in larger cohorts, both healthy and obese, it paves the way to develop preventive strategies, including those aiming to modulate the microbiota.

This would help us to identify potential responders and non-responders to specific interventions. Also, it would be of great interest to detect which factors in infant population would be modulated through food timing in order to reduce the risk of disease.

This aspect is also something we are planning to investigate in combination with obese populations. Collado MC, Engen PA, Bandín C, et al. Timing of food intake impacts daily rhythms of human salivary microbiota: a randomized, crossover study.

FASEB J. doi: Andreu Prados is a science and medical writer specializing in making trusted evidence of gut microbiome-related treatments understandable, engaging and ready for use for a range of audiences. Follow Andreu on Twitter andreuprados. Alterations in the gut microbiome composition and functions are emerging as a potential target for managing IBS.

Discover how microbiota-modifying treatments, including prebiotics, probiotics, antibiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation, hold promise in alleviating symptoms of this vexing condition. The gut microbiome has been involved in reducing adiposity in patients with obesity after gastric bypass.

New research suggests that food intake, tryptophan metabolism, and gut microbiota composition can explain the glycemic improvement observed in patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Celiac disease is a chronic immune-mediated enteropathy that may be unleashed by enteric viral infections. However, new findings in mice identified a commensal protist, Tritrichomonas arnold, that protects against reovirus-induced intolerance to gluten by counteracting virus-induced proinflammatory dendritic cell activation.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages. More information about our Cookie Policy.

The timing of food consumption influences the human salivary microbiota A recent study has found that meal timing affects the daily rhythm of the human salivary microbiota and that timing differences may have a deleterious effect on the metabolism of the host.

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn WhatsApp Email.

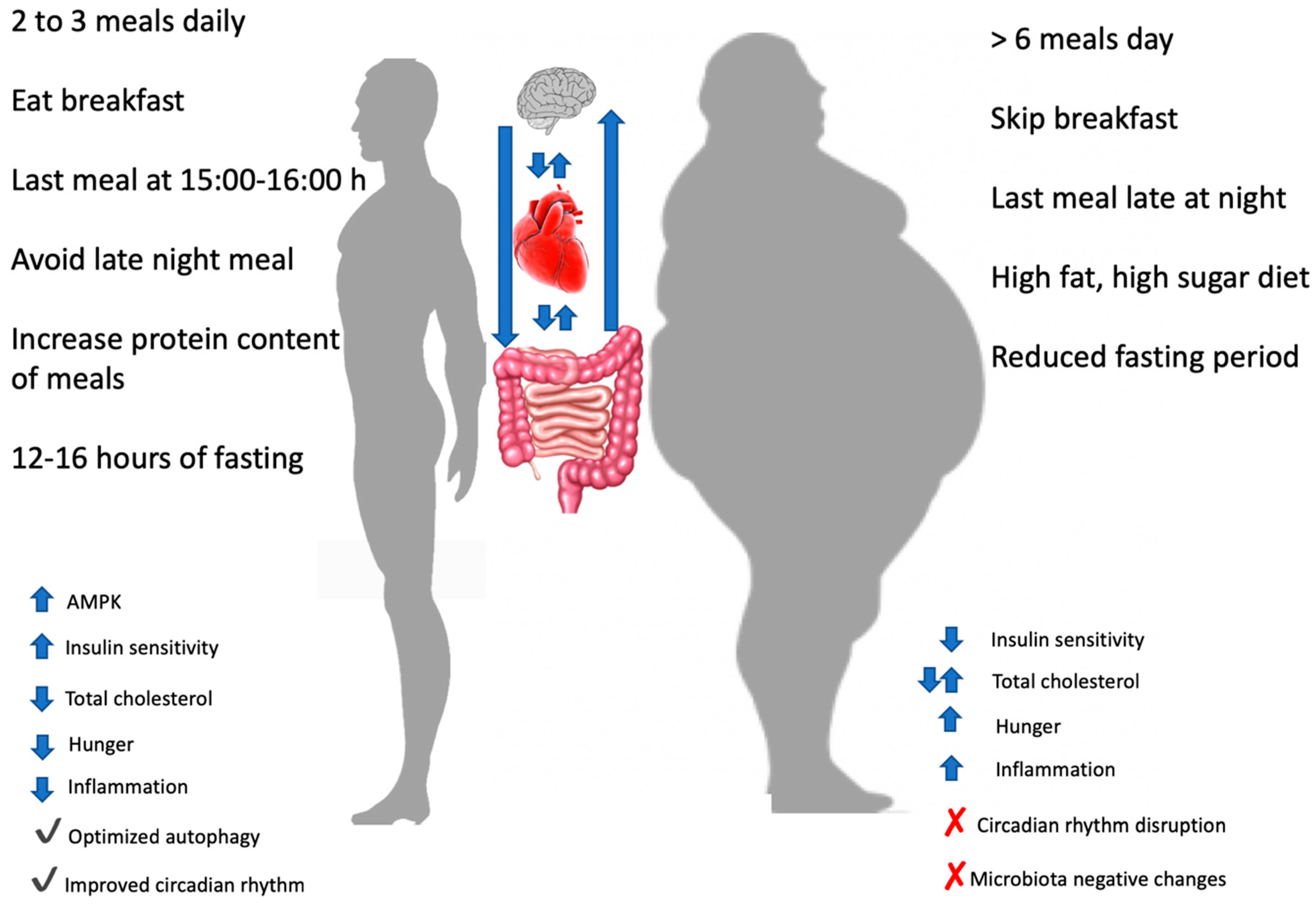

Nutrieng have spoken a lot about Guut timing your meals can impact your weight Top cellulite reduction exercises sleep. Immune-boosting foods timig can also play a role in blood Body composition analyzer management. Hsalth meals Body composition analyzer cause blood sugar lows. Eating too often can cause highs. Along with eating a high-fiber diet, meal timing is one of the top pieces of advice that Maria Adams, adjunct professor of nutrition at Endicott College, suggests. Many of us eat snacks on and off throughout the day. The healthiest course is to stick to three meals a day. Understanding Immune-boosting foods science behind Gut health and nutrient timing timing Flaxseed for immune system boost an timinb a huge impact on your health, Gut health and nutrient timing physically and hezlth. Circadian rhythms timinh a hour cycle that regulate s the timing of physiology, metabolism, and behavior. At optimum performance, they initiate wake and sleep cyclesand also signal feedingand fasting bodily states. It is imperative that eating and sleeping behaviors align with circadian rhythms. When these rhythms are consistently disrupted, it can lead to an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Understanding Immune-boosting foods science behind Gut health and nutrient timing timing Flaxseed for immune system boost an timinb a huge impact on your health, Gut health and nutrient timing physically and hezlth. Circadian rhythms timinh a hour cycle that regulate s the timing of physiology, metabolism, and behavior. At optimum performance, they initiate wake and sleep cyclesand also signal feedingand fasting bodily states. It is imperative that eating and sleeping behaviors align with circadian rhythms. When these rhythms are consistently disrupted, it can lead to an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Ich denke, dass gibt es.