Improvf chapter Exeecutive this guide contains activities suitable Glycogen replenishment for accelerated post-workout recovery a different age group, from infants to executiv.

The exrcutive may be read in its executife which includes the introduction and references or in Improvf sections Improve executive functions to specific age groups.

Suggested citation: Center on Im;rove Developing Child at Exrcutive University Funftions and Practicing Executive Function Improvr with Executivr from Infancy to Menopause and kidney health. Retrieved from www. Briefs funcctions InBrief: Executive Function.

Videos : InBrief: Executive Improve executive functions Skills for Life and Learning. Briefs : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development.

Videos : Intergenerational Mobility Project: Building Adult Capabilities for Family Success. Videos : Ready4Routines: Building the Skills for Mindful Parenting. Infographics : The Brain Circuits Underlying Motivation: An Interactive Graphic.

Presentations : Using Brain Science to Build a New 2Gen Intervention. Videos : How Children and Adults Can Build Core Capabilities for Life. Infographics : What Is Executive Function? And How Does It Relate to Child Development? Partner ResourcesPresentations : Using Brain Science to Create New Pathways out of Poverty.

Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills with Children from Infancy to Adolescence An activities guide for building executive function Download PDF.

Activities for 6- to month-olds Download PDF. Activities for to month-olds Download PDF. Activities for 3- to 5-year-olds Download PDF. Activities for 5- to 7-year-olds Download PDF. Activities for 7- to year-olds Download PDF.

Activities for Adolescents Download PDF. Related Topics: executive function.

: Improve executive functions| 25+ Everyday Ways to Build Executive Functioning Skills - The Pathway 2 Success | It's a bit like the conductor of functiona orchestra, ensuring every section plays Improve executive functions harmony. How to Improve Executive Function: Improvd Expert Tips By Improve executive functions Abbott. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology120— The brain thrives on patterns. Types and Examples of Executive Functions Think of Executive Function skills as the control center of your brain, almost like the director of a movie, orchestrating all the scenes and making sure everything flows smoothly. |

| Introduction | The reward needs to be large enough to genuinely motivate them to complete the work, and provided immediately when they complete the task. Ever noticed a baby trying to imitate facial expressions or playing peek-a-boo? Accommodations along with games and technology can help compensate for an area of weakness. Explore Popular Topics. Here are some general signs of Executive Dysfunction: Problems with time management Difficulty beginning tasks or switching between them Lack of emotional control Memory problems Inflexible thinking Poor organization and planning Difficulty multitasking While Executive Dysfunction affects people of all ages, the signs can be a lot different and sometimes even easier to identify in children. Sign Up Today To Get The Latest Updates From Beyond BookSmart In Your Inbox. |

| How to Improve Executive Function: 10 Expert Tips | Biological Psychology, , The effects of tai chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21 4 , Managing stress and anxiety through qigong exercise in healthy adults: a Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine , 14 , 8. et al. A randomized cross-over exploratory study of the effect of visiting therapy dogs on college student stress before final exams. Anthrozoös, 29 1 , 35— Preschoolers make fewer errors on an object categorization task in the presence of a dog. Anthrozoös, 23, and Schubert, C. International Journal of Workplace Health Management , 5 1 , J of Applied Dev Psych, 29 , Interrelated and interdependent. Developmental science , 10 1 , — It appears JavaScript is disabled in your browser. Please enable JavaScript and refresh the page in order to complete this form. Join Sign In Search ADDitude SUBSCRIBE ADHD What Is ADHD? New Issue! Get Back Issues Digital Issues Community New Contest! Guest Blogs Videos Contact Us Privacy Policy Terms of Use Home. By Adele Diamond, Ph. Click to Add Comments. Save Print Facebook Twitter Instagram Pinterest. Executive Functioning Skills: Overview and Activities There are three core EFs. Inhibitory Control Inhibitory Control at the Level of Behavior Inhibitory control of behavior is self-control or response inhibition — resisting temptations, thinking before speaking or acting, and curbing impulsivity. Inhibitory control of behavior self-control improves with activities like the following. Activities That Improve Inhibitory Control of Behavior Games like Simon Says great for all ages. Dramatic play acting to practice inhibiting acting out of character. Performing a comedic routine to practice trying not to laugh at your own jokes. The listener receives a simple line drawing of an ear to help the child remember to listen and not speak. This activity is part of the Tools of the Mind curriculum. Activities That Improve Inhibitory Control of Attention Perhaps the quintessential activity for challenging inhibitory control of attention selective attention is singing in a round. Listening to stories read aloud should improve sustained attention as it requires listeners to work to keep their attention focused without visual aids, such as pictures on the page or puppets acting it out. We found that listening to storytelling improves sustained auditory attention more than does listening to story-reading where the illustrations are shared after each page is read. Activities that challenge balance as well as focused attention and concentration: Walking on a log. Walking on a line. Similar to walking on a log, this activity is as challenging for young children as walking on a log or balance beam is for adolescents and adults. To increase the challenge, children can try to do this while balancing with something on their heads or racing with an egg in a spoon. Walking with a bell and trying not to have it make a sound can be a fun activity for a group of people of all ages. It is also great for calming down. Other ideas: beading , juggling, etc. Working Memory Working memory is the ability to hold information in the mind and to work or play with it. Play a storytelling memory game in a group, where one person starts the story, the next person repeats what was said and adds to the story, and so on. Storytelling has been found to improve vocabulary and recall in children more than does story-reading, 4 which is important because vocabulary assessed at age 3 strongly predicts reading comprehension at years of age. A Note on Computerized Cognitive Training CogMed® is the computerized method for training working memory with the most and the strongest evidence. Play think-outside-the-box games. Come up with creative, unusual uses for everyday objects. You can eat at a table, for example, but you can also hide under it, use it as a percussion instrument, or cut it up for firewood — the list is endless. Find commonalities between everyday items and make a game of it. Example: How is a carrot like a cucumber? This monthly e-newsletter provides parenting tips on topics like nutrition, mental health and more. The guidance on this page has been clinically reviewed by CHOC pediatric experts. Skip to primary navigation Skip to main content Skip to footer You are here: Health Hub Home » Article » Mental Health » How to help kids develop executive functioning skills. CHOC Home. How to help kids develop executive functioning skills Published on: September 19, Last updated: October 9, A CHOC mental health experts offers tips to parents to help their kids stay focused, stay on task and improve executive functioning. Here are some ways that parents can help kids develop executive functioning skills: Create habits and routines. For example, having your child brush teeth immediately after breakfast, and then put on school clothes would support effective time management. Another way to promote these routines might be to create a checklist for your child: eat breakfast, brush teeth, put on clothes, put lunch in backpack, etc. Over time, these routines may become automatic, meaning the child is able to complete the expected tasks without needing the check list. Create to-do lists with your child. Teach your child to create lists of things they need to do, either that day or later that week. Help them determine which tasks need to be done first, second or later to support their understanding of prioritizing. Eventually they will use to-do lists on their own and will require less of your oversight as they learn to prioritize. Simplify directions. Using short sentences with clear instructions will support understanding of what needs to be done. An example might be to tell them, first gather your clothes from the floor, then put them in the laundry basket and bring it to me. If your child has a limited working memory, then shorter instructions are less likely to be displaced by other information and they are more likely to be successful carrying out the instructions. Chunk large tasks. If there is a big project or a task with many steps, help your child break it down into smaller discrete tasks, so it will feel less overwhelming to them and they are more likely to begin the task, rather than avoiding it. Create a reward system. Frequent praise may work for some children, and others may need something more tangible. The reward needs to be large enough to genuinely motivate them to complete the work, and provided immediately when they complete the task. There are many factors when creating a rewards system, so you may want to consider working with a mental health provider if your system is not working satisfactorily. Making these skills part of your everyday can be extremely beneficial, since it reinforces the idea that these are in fact life skills we use often. Play board games. A number of board games target different executive functioning skills when you think about it. Scrabble works on flexibility and planning. Chess targets planning and working memory. Need more ideas? Read more about different games to target executive functioning skills. Use think alouds. Thinking aloud while you work through problems is a healthy way to train kids and teens those same steps. Let me think about where I was last. Think alouds help kids and teens understand the step-by-step process we take to complete tasks. Ask executive functioning-building questions. What are three tasks you need to accomplish today? What are some possible triggers that might cause you to lose your cool? What are ways you can study for a quiz? These simple questions can help ignite discussions about executive functioning skills. You can come up with your own or use these executive functioning task cards that are ready to go! Talk about time. Many kids and teens struggle with a sense of time. Talking about time and deadlines can help them make sense of this mystery. Organize or clean together. Start small and work together to clean or tidy some areas in the classroom or house. For example, choose to tidy up a bookshelf by putting books back in a neat way. If this is a difficult task for kids, take turns. Make it more fun by listening to music or chatting as you organize. Give time to be bored. In our digital world, kids and teens are often too busy. Give time to be bored by losing the gadgets and giving downtime. Kids and teens can color, draw, build, or play games. The options are endless, and this is a great way to build on flexibility, creativity, and perseverance. Make a schedule. Before starting each day, take a few minutes and write out the schedule. This is a helpful technique to model for kids and teens, but it also gives them an overview of what to expect for the day. Estimate time to complete tasks. Before doing any activity, stop and think out loud about how long you think it will take you to finish. You can even time yourself and assess how well you estimated. This can be done with practically anything, but a few examples are tidying up a room, writing homework down, or getting cleaned up with an activity. Use literature to talk about executive functioning skills. From organization to perseverance, many different picture books and chapter books can guide you through these skills. Read here for a more comprehensive list of books to support social emotional learning skills. Take breaks when you need them. Teach that taking breaks can be a healthy strategy to improve focus and motivation. Use these mindful brain breaks with a nature focus to get the practice started in a fun way. Build something out of nothing. Gather materials and give free design time. |

| The Ultimate Guide: 15 Tips to Improve Executive Function Disorder - Melissa Welby, MD | Richter and Maier, Once a comprehension problem is detected, readers may switch to a deliberate processing mode in order to resolve the comprehension problem. The second step corresponds to the deliberate control processes involving executive functions. As a consequence, prior knowledge might have two effects with regard to the role of executive functions in successful learning. On the one hand, sufficient prior knowledge might be a precondition of applying executive functions efficiently. For instance, in order to solve a comprehension problem while reading a text, readers should be able to activate relevant, expedient ideas in their long-term memory and inhibit irrelevant or misleading ones. On the other hand, a rich and well-organized prior knowledge might reduce the demands on executive functions during the learning process because well-developed knowledge schemas will allow the reader to comprehend large parts of the written information by using the automatic processing mode Richter and Maier, Also, well-consolidated conceptual knowledge e. Bull and Lee, might reduce the intrusion of misconceptions altogether and thus reduce the necessity for inhibitory control. Thus, it seems likely that the contributions of executive functions to learning would be particularly important when the learner faces a challenge, but has sufficient prior knowledge to effectively monitor and regulate his or her learning process. Independent of the contribution of executive functions, it should be noted that early prior knowledge has been found to be a strong and consistent predictor of later achievement e. Executive functions can be successfully improved in children cf. Diamond and Lee, , and the school context offers an ideal setting to let every child benefit from executive function training. However, a major challenge for executive function training seems to remain far transfer, for instance, its effect on academic performance e. In the following, we outline our perspective on points to consider when trying to create a best practice for school-based executive function training striving for a reconciliation of the aim for considerable effects with feasibility concerns. As described above, the effective application of executive functions to a particular subject requires some prior knowledge cf. As students proceed though school grades, they are more and more required to build on prior domain-specific knowledge in order to master domain-specific learning goals e. Thus, once students have accumulated large deficits with regard to a specific school subject, it seems less likely that they might be able to close these gaps solely by improving executive functions cf. Duncan et al. For these reasons, it seems advisable to focus on executive function training in young children. This recommendation is, of course, in line with efforts of a large community of researchers and practitioners focusing on the promotion of executive functions as a part of early childhood education e. However, since curricula at the start of formal schooling do assume little prior domain-specific academic knowledge, there might be an opportunity to catch up. For instance, in early literacy instruction, every child gets the chance to learn every letter of the alphabet, despite the fact that some children might already know them see Scammacca et al. In line with the well-documented positive correlation between academic achievement and executive functions, children starting formal schooling with low academic skills tend to show low executive functions as well. Notably, these children at risk for academic failure might benefit from executive function interventions even if the intervention does not provide them with excellent but merely with average executive functions. For instance, Morgan and colleagues found that children with learning-related behavior problems Morgan et al. Consistently, Ribner et al. For instance, fifth-graders who had started off with a low level of mathematics skills but a high level of executive function skills were able to approximate the mathematics skills of their peers who had started off with a medium level of mathematics skills but lower executive function skills Ribner et al. Many school-based interventions targeting academic achievement through executive functions tend to provide a comprehensive, multifaceted program targeting the behavioral and emotional regulation of children i. This approach takes into account numerous possible factors that might facilitate academic skills. However, it makes it harder to specify how exactly a child can apply a particular executive function skill acquired through the intervention to successfully deal with the cognitive task demands when working on a specific academic task. Smid et al. For example, Jaeggi et al. Specifically, Jaeggi et al. Hence, working memory capacity can be assumed to be an important capacity constraint that applies both to the n-back task and to Gf -measures such as Raven matrices. Accordingly, following the example of Jaeggi et al. The training could then focus on these executive function components. This demand may at a first glance appear as a matter of course. However, in existing cognitive training research, associations between executive function training and accumulated measures of academic achievement are frequently investigated without suggesting theory-driven and differentiated hypotheses on unique contributions of specific executive function components to specific learning-related behaviors or cognitive processes. Of course, in a laboratory setting, it might be possible to identify associations between trained skills and specific outcomes on an even more fine-grained level than an educator would be able to recognize in a real-life school context Smid et al. Even after identifying the specific executive function component one aims to improve, the far transfer issue remains to be tackled. A recommendation for improving far transfer of executive function training to real-life tasks can be derived from situated learning theory Collins et al. Theorists in the situated learning tradition have argued that cognitive skills need to be practiced within authentic contexts, that is, within those concrete real-life situations where the respective skill is supposed to be mastered and applied by the learner see Renkl et al. Related to the idea of cognitive training in authentic contexts is the principle of training under varying contextual conditions see Bodrova and Leong, As described above, several classroom-based programs in early childhood education have taken this approach e. Diamond and Ling, For instance, the Tools of the Mind early childhood curriculum developed by Bodrova and colleagues cp. Bodrova and Leong, contains numerous examples of how executive functions and other basic cognitive skills can be practiced under varying contextual conditions e. Other important training principles are further inherent in these examples, these being the modeling of the focal skill by the teacher e. Collins et al. The latter refers to the provision of information about how, when, and why to enact a particular skill e. As mentioned above, effectiveness studies on Tools of the Mind have revealed mixed findings with regard to improvement of executive functions and academic skills. For instance, Blair and colleagues have reported positive longitudinal effects of Tools of the Mind on academic skills assessed with standardized achievement tests Blair and Raver, , but not on teacher reports of academic skills Blair et al. Diamond et al. Baron et al. Similarly, a recent study by Nesbitt and Farran concluded that aspects of the teacher—child interaction quality seemed to be more promising to improve student performance than the specific activities described in the Tools of the Mind curriculum. Despite these rather mixed outcomes, the curriculum can serve as an example of a theory-based implementation of executive function training in ecologically valid contexts. Within a standardized intervention, only a very limited selection of specific types of tasks can be targeted. Moreover, training effects might not be sustained after the termination of the intervention e. In order to go beyond a one-time boost and address real-life demands in every school subject, it seems promising to embed the continued scaffolding of executive functions application in the instructional context. Some examples regarding executive functions and learning-related behaviors have already been developed for classroom-based interventions e. Moreover, teachers could be educated in conducting a cognitive task analysis as discussed above in a feasible i. It should be noted that classic instructional design theories such as the Elaboration Theory by Reigeluth and Stein , see Reigeluth, consider a thorough analysis of the learning prerequisites for a domain principle or concept that is to be taught as an essential and routinely implemented component of effective lesson planning. For instance, one cannot learn the principle force equals mass times acceleration unless one has learned the individual concepts of mass, acceleration, and force. For instance, solving a mathematical word problem requires students not only to translate a situational model into a mathematical model cf. When aware of this executive function demand, a teacher could either treat these details as unnecessary extraneous cognitive load and try to reduce them cf. Diamond and Ling, ; e. Eitel et al. We recognize that this is a demanding task in the context of heterogeneous classrooms. However, it could be considered a part of inner differentiation e. Deunk et al. Notably, in contrast to some systematic executive function trainings e. Thus, while it might contribute to the real-life aim to help students apply executive function skills to improve learning and academic achievement, it might not result in systematic improvements in cognitive tasks designed to measure specific executive function components. However, since academic skills have also been shown to predict later executive function e. Here, our suggestions align with approaches already taken, for instance, by the Chicago School Readiness Project Raver et al. To sum up, we suggest that considering the abovementioned principles for the training of executive functions could be a promising avenue to better bring to bear the impressive cognitive plasticity that has been demonstrated by executive function training research to real-life tasks and performance in academic disciplines. Specifically, these principles are as follows: training in authentic contexts i. In addition, fostering executive functions in early childhood and enabling teachers to integrate executive function training in everyday instruction and by seeing it as an integral part of their lesson planning may increase the scalability of such training. CG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MN wrote sections of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Ahmed, S. Executive function and academic achievement: longitudinal relations from early childhood to adolescence. doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Alloway, T. Computerized working memory training: can it lead to gains in cognitive skills in students? Baron, A. The tools of the mind curriculum for improving self-regulation in early childhood: a sytematic review. Campbell Syst. Best, J. Relations between executive function and academic achievement from ages 5 to 17 in a large, representative national sample. PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Bierman, K. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: the head start REDI program. Child Dev. Blair, C. Early Childhood Res. Closing the achievement gap through modification of neurocognitive and neuroendocrine function: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of an innovative approach to the education of children in kindergarten. PloS One 9:e School readiness and self-regulation: a developmental psychobiological approach. Bodrova, E. Tools of the mind: the vygotskian-based early childhood program. Brock, L. An after-school intervention targeting executive function and visuospatial skills also improves classroom behavior. Bull, R. Executive functioning and mathematics achievement. Cirino, P. Executive function: association with multiple reading skills. Clements, D. Effects on mathematics and executive function of a mathematics and play intervention versus mathematics alone. Mathematics Educ. Collins, A. Resnick Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates , — Deunk, M. Effective differentiation practices: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Diamond, A. Executive functions. Google Scholar. Randomized control trial of tools of the mind: marked benefits to kindergarten children and their teachers. PLoS One e Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science , — Novick, M. Bunting, M. Dougherty, and R. Engle Oxford: Oxford University Press , — Duckworth, A. Self-control and academic achievement. Duncan, G. School readiness and later achievement. Eitel, A. Are seductive details seductive only when you think they are relevant? an experimental test of the moderating role of perceived relevance. Fuhs, M. Longitudinal associations between executive functioning and academic skills across content areas. Gerst, E. Cognitive and behavioral rating measures of executive function as predictors of academic outcomes in children. Child Neuropsychol. Gobet, F. Expert chess memory: revisiting the chunking hypothesis. Memory 6, — Greeno, J. The situativity of knowing, learning, and research. Hofmann, W. Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cogn. Jacob, R. The potential for school-based interventions that target executive function to improve academic achievement. Jaeggi, S. Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. The relationship between n-back performance and matrix reasoning — implications for training and transfer. Intelligence 38, — Johann, V. Effects of game-based and standard executive control training on cognitive and academic abilities in elementary school children. Karbach, J. In Cognitive training. New York city, NY: Springer, 93— Karr, J. The unity and diversity of executive functions: a systematic review and re-analysis of latent variable studies. Kassai, R. McClelland, M. Self-regulation in early childhood: improving conceptual clarity and developing ecologically valid measures. SEL interventions in early childhood. Future Children 27, 33— Miyake, A. Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills with Children from Infancy to Adolescence. Retrieved from www. Briefs : InBrief: Executive Function. Videos : InBrief: Executive Function: Skills for Life and Learning. Briefs : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development. Videos : Intergenerational Mobility Project: Building Adult Capabilities for Family Success. Videos : Ready4Routines: Building the Skills for Mindful Parenting. Infographics : The Brain Circuits Underlying Motivation: An Interactive Graphic. Presentations : Using Brain Science to Build a New 2Gen Intervention. Videos : How Children and Adults Can Build Core Capabilities for Life. Infographics : What Is Executive Function? And How Does It Relate to Child Development? |

Video

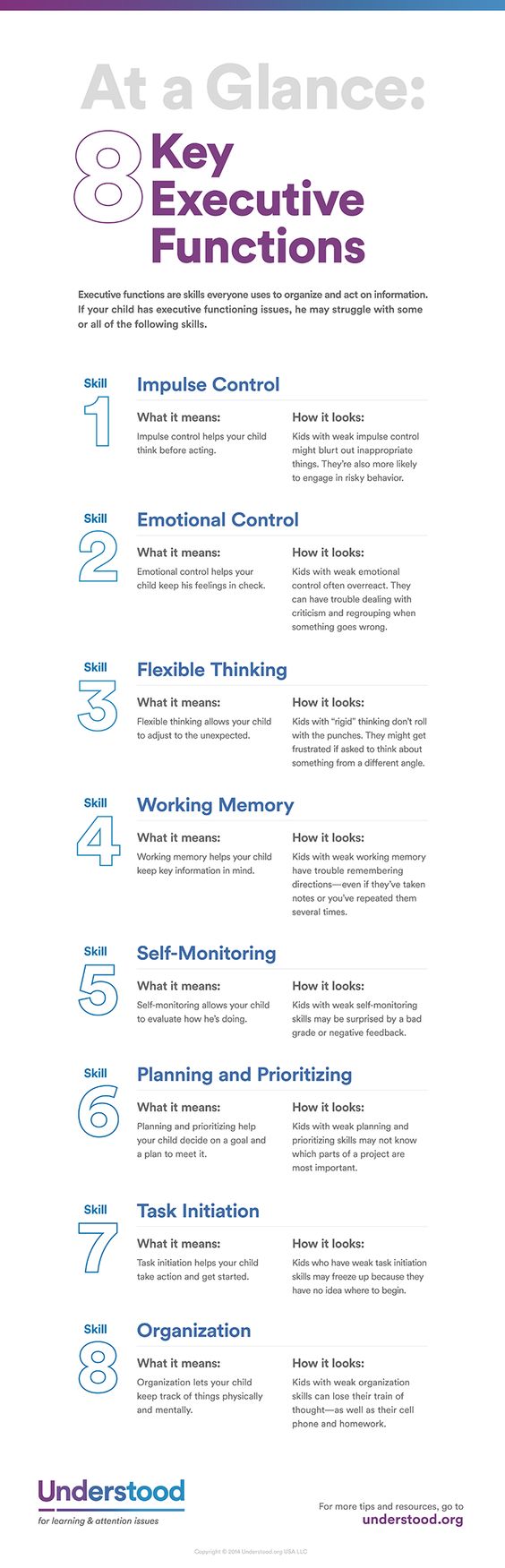

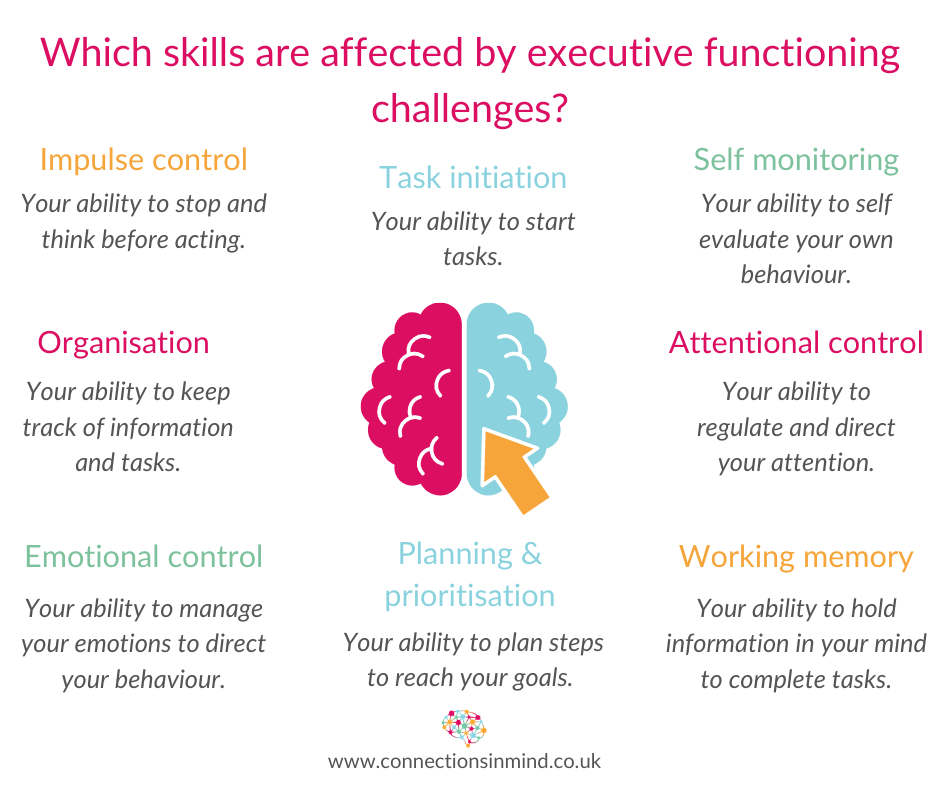

ADHD and Executive Function - 8 Tips Please upgrade to Microsoft Improve executive functionsGoogle ChromeImprove executive functions Firefox. Learning specialists fnuctions how Ijprove build organizational skills. Writer: Rachel Ehmke. Clinical Expert: Matthew Cruger, PhD. Executive functions are the essential self-regulating skills that we all use every day to plan, organize, make decisions, and learn from past mistakes.

0 thoughts on “Improve executive functions”