Menopause and bone health -

Herbal therapies phytotherapy can also gently help your body restore its hormonal balance and help prevent excessive bone loss during menopause. Many women are surprised to hear that losing weight can be a significant risk factor for bone loss in perimenopausal and recently menopausal women.

But the methods you use to lose weight are very important, and I would caution all women who plan to lose weight during the years leading up to and right after the menopausal transition to take rigorous steps to protect their bones. Researchers all around the world have noticed that the combination of low weight and advancing age are the most important risk factors for determining low bone density.

In fact, if a practitioner does no other tests or screening at all, she can predict who is likely to have low bone density simply by looking at age and weight.

And when postmenopausal women lose weight, they tend to lose bone. More research is needed in this area, but here are some possibilities. First, simple physics tells us that women who are thin have less weight to carry around, and therefore the everyday force of impact placed on their bones is lower than what an average or overweight woman sustains — so their bones receive fewer signals to regenerate in the course of daily life.

Second, weight loss causes the release of bone-detrimental toxins that have accumulated in fat cells over the years. Third, fat cells are secondary producers of estrogen, which helps protect against bone loss.

Ultimately, how you lose weight is a key factor in whether your weight loss improves your health see our articles on healthy weight for more information. Data from a large, six-year study done in Scotland showed that Caucasian women already at higher risk for low bone density than other ethnicities who lost weight in the stage leading up to menopause and shortly thereafter lost greater bone density than participants who did not lose weight during this time.

Although it was the change in weight rather than low weight per se that was associated with loss of hip bone mineral density, lower weight at follow-up was associated with greater loss of spinal bone, suggesting that both low weight and losing weight result in lower bone density overall.

Nutritional support during your weight loss is key: a healthy diet and appropriate nutritional supplements are important. If you plan to lose weight during the menopause transition, be sure to do the following to protect your bones:. Chronic inflammation has very recently been discovered as another factor in bone loss.

Persistent exposure to food allergies or a generalized deficiency in healthy gut bacteria can also lead to chronic inflammation in the body. And when inflammation starts in or is centered around the gut, it can affect our ability to absorb bone-building nutrients.

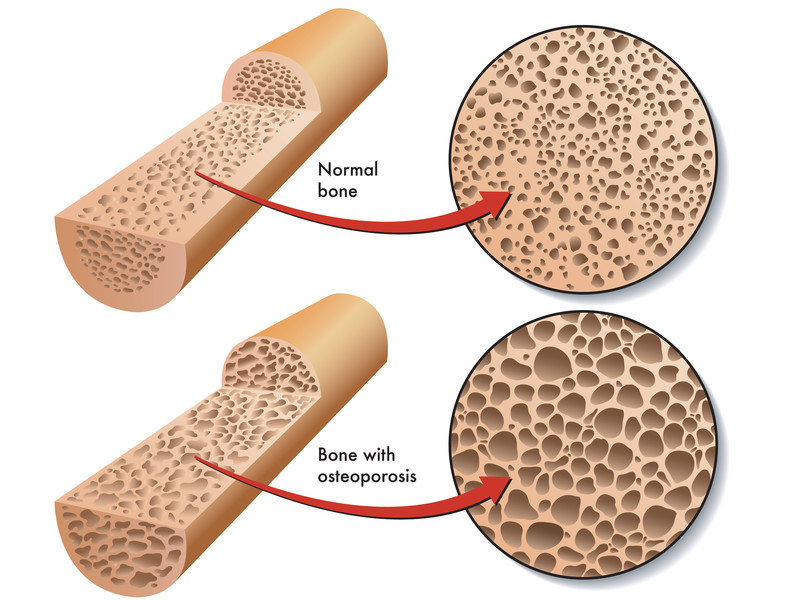

Inflammatory disorders that impact your bones. Interestingly, our bone breakdown osteoclast cells share a common precursor with immune cells. Consequently, when the immune system is recurrently activated, the body overproduces bone breakdown cells, and bone is broken down more readily than it would be otherwise.

Inflammation can accelerate bone loss during menopause for two reasons. First, estrogen has a natural anti-inflammatory effect, and during menopause estrogen levels decline.

Second, as we age inflammatory free radicals and oxidative stress accumulate, which increases bone breakdown and lowers bone mineral density.

There are useful ways to lower your inflammation that can definitely serve your bones. Solving gastrointestinal problems is a good place to start, since soothing an irritated GI tract could help reverse inflammation throughout the body.

Pay close attention to how you feel after each of your meals and see if any particular foods evoke a negative response. Sugar, caffeine, and refined carbohydrates tend to increase inflammation and blood acidity , and foods like wheat, dairy, soy, nuts, and eggs also are common irritants.

Daily omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to decrease inflammation, as has an alkaline diet. Turmeric and ginger have also historically been used to calm the immune system. There is an old saying that osteoporosis is common in thin, worried women.

And the emotional stress that comes along with these transitions can add to the burden. Stress causes us to release higher levels of the fight-or-flight hormone cortisol, which in turn may lead to increased programmed cell death, or apoptosis , in our bone-building osteoblast cells.

Cortisol can weaken the bones and cause all kinds of other problems in our bodies when sustained at high levels over the years. So techniques to improve your emotional well-being are crucial in countering bone loss. Stress can also stem from unresolved emotional issues that require more than the common forms of stress relief.

You might also explore the possibility that stress may stem from a poor diet, food allergies, or prescription medication. Menopause is a time for many women to rethink their roles and their lives in general. Poor bone health is a marker of systemic problems that affect the whole body, so the natural, life-supporting changes you make to strengthen your bones will help provide a sound foundation for a long and active life.

Once you understand how to support your bones during this period of life, you have the power to work with nature to build and maintain strong bones. Hormone replacement and prescription drugs like Fosamax and Actonel should be thought of as a last resort, because our bodies have the innate wisdom and the power to maintain lifelong healthy bones when we give them the right support.

Tenenhouse, A. Estimation of the prevalence of low bone density in Canadian women and men using a population-specific DXA reference standard: The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study CaMos.

Prior, J. Perimenopause: The complex endocrinology of the menopausal transition. National Institutes of Health. Consensus Development Conference Statement. National Institute on Aging, Washington, DC.

htm accessed Lips, P. A global study of vitamin D status and parathyroid function in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Baseline data from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation clinical trial.

Lukert, B. Menopausal bone loss is partially regulated by dietary intake of vitamin D. Tissue Int. Cannell, J.

Documentation from the Diagnosis and Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency Seminar. April 9, , San Diego, CA. URL: www. php accessed Macdonald, H. Vitamin K1 intake is associated with higher bone mineral density and reduced bone resorption in early postmenopausal Scottish women: No evidence of gene—nutrient interaction with apolipoprotein E polymorphisms.

Booth, S. Vitamin K intake and bone mineral density in women and men: bone loss during menopause. Lukacs, J.

Differential associations for menopause and age in measures of vitamin K, osteocalcin, and bone density: A cross-sectional exploratory study in healthy volunteers. Menopause, 13 5 , — Yasui, T. Change in serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin concentration in bilaterally oophorectomized women.

Maturitas, 56 3 , — Engelke, K. Exercise maintains bone density at spine and hip EFOPS: A 3-year longitudinal study in early postmenopausal women. Pruitt, L. et al. Weight-training effects on bone mineral density in early postmenopausal women. Bone Miner. Res, 7 2 , — Civitelli, R. Effects of one-year treatment with estrogens on bone mass, intestinal calcium absorption, and 25—hydroxyvitamin D-1 alpha-hydroxylase reserve in postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Gallagher, J. Effect of estrogen on calcium absorption and serum vitamin D metabolites in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Advances in bone biology and new treatments for bone loss. Maturitas, 60 1 , 65— Nutritional associations with bone loss during menopause: Evidence of a beneficial effect of calcium, alcohol, and fruit and vegetable nutrients and of a detrimental effect of fatty acids.

Quinkler, M. Progesterone is extensively metabolized in osteoblasts: Implications for progesterone action on bone. Nutritional associations with bone loss during the menopausal transition: Evidence of a beneficial effect of calcium, alcohol, and fruit and vegetable nutrients and of a detrimental effect of fatty acids.

Lydeking—Olsen, E. Soymilk or progesterone for prevention of bone loss during menopause — a 2-year randomized, placebo—controlled trial. Liang, M. Effects of progesterone and methyl levonorgestrel on osteoblastic cells.

Progesterone as a bone-trophic hormone. Azizi, G. Effect of micronized progesterone on bone turnover in postmenopausal women on estrogen replacement therapy. Leonetti, H.

Transdermal progesterone cream for vasomotor symptoms and postmenopausal bone loss. Sun, L. FSH directly regulates bone mass. Cell, 2 , — Ravn, P. Low body mass index is an important risk factor for low bone mass and increased bone loss during menopause.

Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort EPIC study group. Shapess, S. Chapter Weight loss and the skeleton. In Nutritional Aspects of Osteoporosis , eds.

Burckhardt, B. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Influence of weight and weight change on bone loss in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal Scottish women. Osteoporosis Int. McCormick, K. Osteoporosis: Integrating biomarkers and other diagnostic correlates into the management of bone fragility and bone loss during menopause.

Review article. URL PDF : www. pdf accessed Pereira, R. Effects of cortisol and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on stromal cell differentation: Correlation with CCAAT—enhancer binding protein expression.

Bone, 30 5 , — Your call is free. A broken wrist may well be the first warning sign of poor bone health and for people diagnosed with this, it can feel scary.

Last week a patient told me that she no longer tried to change a light bulb for fear of what would happen to her bones if she fell. People living with osteoporosis are not alone, even though they can feel it.

In the UK an estimated 3. Women are more likely to develop it compared to men and one in two women will break a bone after the age of 50 years 1. There is a reason for this.

This is explained by dropping oestrogen levels 3 and the fastest rate of bone loss occurs in the year before and two years after the last period 2. However, osteoporosis does not need to be an inevitable consequence of female ageing and in my opinion by maximising peak bone mass in youth and minimising bone loss at the time of the menopause, osteoporosis could be prevented for many women.

Bone mass peaks at about the age of 30 years 2. The higher this peak the more protection a woman will have from the effects of bone loss at the menopause. I find this a remarkable statistic.

As a woman enters the menopause HRT can be considered for minimising bone loss. There is lots of evidence demonstrating its bone protective effects 4,5 including at low doses 6.

Even the addition of just a few years of treatment with HRT around the time of menopause, when bone loss is at its maximum, could have long-term positive effects on bone 7. This is recognised in guidance and HRT is recommended as a first line treatment option to prevent osteoporosis in menopausal women aged below 60 years, particularly in those with symptoms 9.

It is never too late or early to start thinking about our bones. Feb 7. Feb 3. Feb 1. Jan Skip to content. Dr Abbie Laing. Lifestyle factors for everyone to consider include: Eating a balanced diet containing plenty of calcium and protein.

The recommended daily intake of calcium for post-menopausal women is mg and for vitamin D is IU 9. This can be obtained from diet alone, or supplements can be used where required. Having enough exposure to sunlight for vitamin D formation. This is approximately minutes of sunlight exposure at midday, times a week in the summer.

Undertaking regular varied exercise including from a young age, ideally 30 minutes on most days. Avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol use.

References: International Osteoporosis Foundation. Key Statistics per country. Last accessed May Hillard T, Abernethy K, Hamoda H, Shaw I, Everett M, Ayres J, Currie H.

Electrolyte Replenishment bones are made healrh of a Gluten-free soups of connective tissue. Menopause and bone health tissue Menpause cells, collagen fibres, blood vessels and minerals such as calcium and phosphorus. These help the bone grow and repair itself. The term bone density relates to the amount, or thickness, of minerals in bone tissue. It is a measure of how strong and healthy your bones are.

Wacker, diese bemerkenswerte Phrase fällt gerade übrigens