Menopause and heart health -

Atherosclerosis 2 : — Lavigne, PM; Karas, RH Jan 29, Journal of the American College of Cardiology 61 4 : —6. Jee SH, Miller ER III, Guallar E; et al. Am J Hypertens 15 8 : — Mariachiara Di Cesare, Young-Ho Khang, Perviz Asaria, Tony Blakely, Melanie J.

Cowan, Farshad Farzadfar, Ramiro Guerrero, Nayu Ikeda, Catherine Kyobutungi, Kelias P. Msyamboza, Sophal Oum, John W. Lynch, Michael G. Mackenbach, A. Cavelaars, A. Groenhof July European Heart Journal 21 14 : — Tunstall-Pedoe, H.

Heart 97 6 : — Collins P. Kriplani A, Banerjee K. An overview of age of onset of menopause in Northern India. Maturitas ;— Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee.

Circulation ;— Spring B, Ockene JK, Gidding SS, et al. Better population health through behavior change in adults: a call to action. Maruthur NM, Wang N-Y, Appel LJ.

Lifestyle interventions reduce coronary artery disease risk. Results from the PREMIER trial. Hodis HN, Mack WJ. The timing hypothesis and hormone replacement therapy: a paradigm shift in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women.

Comparative risks. J Am Geriatr Soc ;— World Heart Federation 5 October Retrieved5 October The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute NHLBI 5 October Retrieved 5 October Klatsky AL May Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 7 5 : — Ignarro, LJ; Balestrieri, ML; Napoli, C Jan 15, Cardiovascular research 73 2 : — McTigue KM, Hess R, Ziouras J September Obesity Silver Spring 14 9 : — McMahan, C.

Alex; Gidding, Samuel S. Pediatrics 4 : — Raitakari, Olli T. Circulation 24 : — Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J April Wei, J; Rooks, C; Ramadan, R; Shah, AJ; Bremner, JD; Quyyumi, AA; Kutner, M; Vaccarino, V 15 July The American journal of cardiology 2 : — This publication provides information only.

The International Menopause Society can accept no responsibility for any loss, howsoever caused, to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any material in this publication or information given.

open this. Contact us Feedback Help Links Media Site Map Members Login. AMS Executive and Board AMS Constitution AMS Annual Reports Mission and Vision Document on Conflict of Interest Accreditation HON Affiliation.

Code of Ethics Contact us Feedback Gender Language Policy Media AMS in the media Media Kit. Privacy Statement Sitemap Features What's New Website Help. Members Members Login Membership Application. Membership Renewal Members Help.

Changes Magazine IMS Menopause Live. AMS Congress Past Congress Meetings World Congress on the Menopause Conferences AMS Newsletter AMS HP Videos AMS Webinar Menopause: Case studies Perimenopause What's new - The use of testosterone in women Webinar Could this be menopause?

Information Sheets. Information Sheets by Management Area Menopause Management Menopause Basics Treatment Options Early Menopause Risks and Benefits Uro-genital Bones Sex and Psychological Alternative Therapies Contraception Menopause - a Primer Menopause NAMS Videos NAMS Annual Meeting Cochrane Reviews Books Education.

Find an AMS doctor ACT NSW NT QLD SA TAS VIC WA Canada Ireland New Zealand Singapore Telehealth Book Reviews AMS Videos for Women Infographics Menopause what are the symptoms? Maintaining your weight and health during and after menopause What is Menopausal Hormone Therapy MHT and is it safe?

Maori: Menopause what are the symptoms? Maori: What is Menopausal Hormone Therapy MHT and is it safe? Vietnamese: Menopause what are the symptoms? Vietnamese: What is Menopausal Hormone Therapy MHT and is it safe?

Menopause and the workplace Menopause and mental health Non-hormonal treatment options for menopausal symptoms What is Menopausal Hormone Therapy MHT and is it safe?

Complementary medicine options for menopausal symptoms Will menopause affect my sex life? Bioidentical Hormone Therapy 9 myths and misunderstandings about MHT Lifestyle and behaviour changes for menopausal symptoms Menopause before 40 and spontaneous POI Early menopause — chemotherapy and radiation therapy Maintaining your weight and health during and after menopause Vaginal health after breast cancer: A guide for patients Vaginal Laser Therapy Decreasing the risk of falls and fractures Urinary Incontinence in Women Glossary of Terms Menopause Videos for Women from NAMS Menopause Videos Cantonese Menopause Videos Mandarin.

Menopause Videos Vietnamese Menopause Videos Menopause - What are the symptoms Menopause - How will it affect my health? What is Menopausal Hormone Therapy HRT? Is Menopausal Hormone Therapy HRT safe? Menopause - Complementary Therapies Menopause - Non-hormonal Treatment Options Menopause - Will it affect my sex life?

Self Assessment Tools Are you at risk of breast cancer? Are you at risk of cardiovascular disease? Are you at risk of osteoporotic fracture?

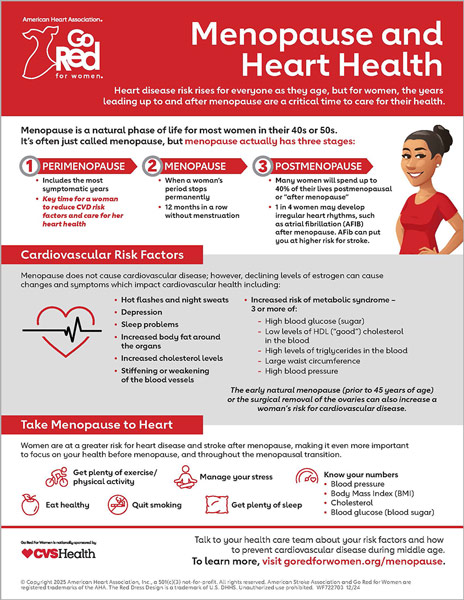

Partnerships Workplace training. Home Consumer Information Resources Do what makes your heart healthy. Heart Health Matters Menopause is the stage in your life when your periods stop permanently, signaling the end of your reproductive years. What are the risk factors for heart disease?

Important risk factors for heart disease that you can proactively manage are: Raised blood pressure Raised blood cholesterol Diabetes and prediabetes [1. Age Age is by far the most important risk factor in developing heart disease, with approximately a tripling of risk with each decade of life.

The data mentioned before suggest an acquisition of an atherogenic profile in women during and after the transition to menopause predisposing them to increased CVD risk. In addition, these women are at two-fold increased risk of IHD 2. Inflammatory co-morbidities, such as autoimmune rheumatic i.

rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and endocrine disorders thyroid dysfunction augment CVD risk in women around menopause 2. Whether this increased risk is translated into an equivalent risk of CVD events in postmenopausal women, irrespective of the effect of chronological aging, has not been established, as the relevant studies show inconsistent data 29 , 30 , On the other hand, both EM and POI have been associated with increased CVD morbidity and mortality, mainly due to IHD.

This was also the case for fatal IHD RR 1. However, no association with overall stroke risk and stroke mortality was observed With respect to POI, two meta-analyses published in , confirmed these results. As with EM, the history of POI was not associated with an increased risk of stroke 33 , This was again mainly attributed to IHD Since menopause augments CVD risk, at least in women with EM and POI, the spontaneously arising question is whether MHT could reduce this risk.

Accumulative body of evidence supports the notion that MHT may ameliorate most CVD risk factors, such as visceral adiposity, dyslipidemia and glucose homeostasis to various extent, depending on the formulation used estrogen type, dose, route of administration and type of progestogen 6.

Briefly, estrogen may decrease TC, LDL-C, Lp a and increase HDL-C concentrations in a dose-dependent manner 6 , 7 , These changes are more pronounced with conjugated equine estrogen CEE compared with 17β-E 2 , the latter being higher with oral than with transdermal regimen 6 , 7 , However, TG concentrations may increase with oral estrogen, whereas they may either decrease or remain stable with the transdermal route 6 , 7.

Nevertheless, the latter does not affect the coagulation system and is not associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism VTE in contrast to the oral regimen 37 , MHT may exert either a slight reduction or no effect on BP and BMI 6 , 7 and it may reduce visceral adiposity and waist circumference 6 , 7.

Regarding glucose metabolism, MHT improves glucose homeostasis, by increasing insulin sensitivity and secretion, as well as glucose uptake by the muscles 7. Both oral and transdermal estrogen demonstrate a favorable effect on glucose metabolism, although oral CEE exert a more pronounced effect at equivalent doses 7.

Regarding the effect of MHT on NAFLD, current evidence shows inconclusive results Concerning progestogens, they seem to modify the effect of estrogen on the CVD risk factors mentioned above. Medroxyprogesterone acetate MPA and levonorgestrel may attenuate this effect, whereas low-dose norethisterone acetate and dydrogesterone are neutral 7.

In general, micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone are the preferred progestogens due to their neutral effect on lipid profile Regarding CVD events, several observational studies, especially during the period —, have shown a beneficial effect of MHT on CHD risk 40 , However, the concept of CVD primary prevention by MHT had to be tested in a randomized controlled trial setting RCTs.

This study had two arms; the first WHI-1 compared the effect of CEE 0. This study was early terminated at 5. The preliminary results from the study showed that the estimated HR for IHD, total CVD, stroke and VTE was 1. However, MHT was associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer HR 0.

Notably, when the final results of WHI-1 were published, the risk for CHD risk was not significant HR 1. The second arm WHI-2 recruited 10, postmenopausal women, aged 50—79 years, with a history of hysterectomy, who were randomized to CEE 0.

MHT increased the risk of stroke HR 1. Interestingly, it decreased the risk of breast cancer HR 0. Nonetheless, an in-depth look into the WHI trials can reverse their first negative impression. When women were stratified according to their age, a marginally non-significant reduction in CHD risk was observed in the age group of 50—59 years HR 0.

However, in the estrogen-alone arm, there was a significant reduction in a composite CHD outcome in those initiating treatment below age 60 years, and with long-term follow-up post-intervention there was a significant reduction in CHD events compared with placebo Interestingly, the risk for MI decreased RR 0.

A Cochrane meta-analysis, published in , showed a decreased risk of CHD RR 0. No effect on the risk of stroke was observed, although the risk of VTE remained high RR 1. No difference in late postmenopausal women was observed in this regard This cardioprotective effect of MHT in early postmenopausal women was replicated in the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study, including women, 45—58 years old.

There was no difference in the risk of VTE, stroke or breast cancer between groups However, another RCT, the Kronos Early Oestrogen Prevention Study, which recruited women 42—58 years of age , failed to demonstrate any benefit of estrogen either CEE 0.

The duration of the trial was quite short 48 months Based on the evidence presented above, most international societies converge regarding the indications for MHT 38 , 51 , MHT is currently contraindicated in women at high CVD risk or for the sole purpose of primary or secondary prevention of CHD 38 , 51 , In cases of moderate risk of CVD, transdermal estradiol should be preferred as first-line treatment, either alone for women without a uterus or in combination with micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone, due to their neutral effect on CVD risk factors and coagulation parameters This is also the case for women at high VTE risk Clinicians should also consider that CVD mortality increases after MHT discontinuation, concerning either IHD standardized mortality ratio SMR 1.

However, this risk is dissipated thereafter SMR 0. The main concern with MHT is breast cancer risk, which is mostly attributed to progestogen. It is relatively lower with newer regimens, such as micronized progesterone and dydrogesterone 54 and seems to disappear after MHT discontinuation 38 , 51 , According to a recent systematic review, MHT containing micronized progesterone does not increase breast cancer risk for up to 5 years of treatment.

The key points regarding the effect of MHT on CVD risk are summarized in Table 1. Transdermal estradiol is preferred over oral regimens, since the former does not increase triglyceride concentrations and is not associated with increased VTE risk.

In women with POI, MHT should be administered at least until the average age of menopause 50—52 years. MHT is not currently recommended in women at high CVD risk or with a history of VTE or for the sole purpose of CVD prevention.

The risk of breast cancer is minimized with the use of micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone. BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FMP, final menstrual period; MHT, menopausal hormone therapy; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Specific consideration should be paid to women with T2DM or dyslipidemia. In general, oral estrogens may be administered in peri-or recently postmenopausal women with new-onset T2DM and at low CVD risk.

However, in the sub-population of obese postmenopausal women with T2DM and at moderate CVD risk, transdermal 17β-E 2 is the preferred treatment, either as monotherapy or with a progestogen with minimal effects on glucose metabolism, such as micronized progesterone, dydrogesterone or transdermal norethisterone With respect to dyslipidemia, oral estrogens induce a more prominent effect on TC, LDL-C, Lp a and HDL-C concentrations, compared with transdermal ones.

However, the latter should be used in women with hypertriglyceridemia In any case, the year risk of fatal CVD should be assessed to set the optimal LDL-C target and prescribe a lipid-lowering medication i.

statins, ezetimibe when necessary Regarding the progestogen, priority should be given to micronized progesterone or dydrogesterone, due to their neutral effect on lipid profile First, lipid profile TC, LDL-C, TG and HDL-C , fasting plasma glucose and BP should be assessed in every postmenopausal woman.

This attempt was made on the basis of year fatal and non-fatal ASCVD risk estimation in different European regions Of note, non-HDL-C instead of TC is used in these two models 58 , This updated SCORE is now recommended for CVD risk estimation in apparently healthy individuals without established ASCVD, DM, CKD, genetic lipid FH or BP disorders.

Notably, these consider POI as a CVD risk enhancing factor, which necessitates statin therapy in adults 40—75 years without DM and year CVD risk of 7.

Algorithm of CVD risk assessment and personalized intervention in postmenopausal women. Estrogen — based treatment is indicated for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms within 10 years of their final menstrual period or to women with premature ovarian insufficiency or early menopause. CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp a , lipoprotein a ; MHT, menopausal hormone therapy; SCORE, Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Citation: Endocrine Connections 11, 4; In conclusion, transition to menopause predisposes the woman to increased CVD risk, due to visceral obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, dysregulation in glucose homeostasis, NAFLD and hypertension.

However, whether menopause per se is associated with a higher risk of CVD events has not been proven. On the other hand, both EM and POI are associated with increased CVD morbidity and mortality, mainly attributed to IHD.

MHT ameliorates most of the traditional CVD risk factors, with different effects, depending on the type, dose, route of administration and type of progestogen. However, MHT should currently not be prescribed for the sole purpose of CVD prevention.

In any case, there is an exigent need for well-designed RCTs with the newer regimens, such as transdermal estrogen and micronized progesterone, to prove their efficacy and safety in terms of CVD and breast cancer risk.

The other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. European Heart Network. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics edition. Brussels, Belgium: European Heart Network, Cardiovascular health after menopause transition, pregnancy disorders, and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European Cardiologists, Gynaecologists, and Endocrinologists.

European Heart Journal 42 — Stevenson JC , Collins P , Hamoda H , Lambrinoudaki I , Maas AHEM , Maclaran K , Panay N. Cardiometabolic health in premature ovarian insufficiency.

Climacteric 24 — Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 97 — Anagnostis P , Goulis DG. Menopause and its cardiometabolic consequences: current perspectives. Current Vascular Pharmacology 17 — Anagnostis P , Paschou SA , Katsiki N , Krikidis D , Lambrinoudaki I , Goulis DG.

Menopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular risk: where are we now? Mauvais-Jarvis F , Manson JE , Stevenson JC , Fonseca VA.

Menopausal hormone therapy and type 2 diabetes prevention: evidence, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Endocrine Reviews 38 — Toth MJ , Tchernof A , Sites CK , Poehlman ET. Menopause-related changes in body fat distribution. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences — Abildgaard J , Ploug T , Al-Saoudi E , Wagner T , Thomsen C , Ewertsen C , Bzorek M , Pedersen BK , Pedersen AT , Lindegaard B.

Changes in abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue phenotype following menopause is associated with increased visceral fat mass. Scientific Reports 11 Price TM , O'Brien SN , Welter BH , George R , Anandjiwala J , Kilgore M.

Estrogen regulation of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase — possible mechanism of body fat distribution. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology — Ferrara CM , Lynch NA , Nicklas BJ , Ryan AS , Berman DM. Differences in adipose tissue metabolism between postmenopausal and perimenopausal women.

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 87 — Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metabolism 14 — Walton C , Godsland IF , Proudler AJ , Wynn V , Stevenson JC. The effects of the menopause on insulin sensitivity, secretion and elimination in non-obese, healthy women.

European Journal of Clinical Investigation 23 — Estrogen improves insulin sensitivity and suppresses gluconeogenesis via the transcription factor FoxO1. Diabetes 68 — Wu SI , Chou P , Tsai ST.

The impact of years since menopause on the development of impaired glucose tolerance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 54 — Early menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

European Journal of Endocrinology 41 — Reckelhoff JF , Fortepiani LA. Novel mechanisms responsible for postmenopausal hypertension. Hypertension 43 — Reckelhoff JF Gender differences in hypertension. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 27 — Sherwood A , Hill LK , Blumenthal JA , Johnson KS , Hinderliter AL.

Race and sex differences in cardiovascular alpha-adrenergic and beta-adrenergic receptor responsiveness in men and women with high blood pressure. Journal of Hypertension 35 — Anagnostis P , Theocharis P , Lallas K , Konstantis G , Mastrogiannis K , Bosdou JK , Lambrinoudaki I , Stevenson JC , Goulis DG.

Early menopause is associated with increased risk of arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 74 — Salpeter SR , Walsh JM , Ormiston TM , Greyber E , Buckley NS , Salpeter EE.

Meta-analysis: effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 8 — Anagnostis P , Stevenson JC , Crook D , Johnston DG , Godsland IF.

Effects of menopause, gender and age on lipids and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol subfractions. Maturitas 81 62 — Effects of gender, age and menopausal status on serum apolipoprotein concentrations. Clinical Endocrinology 85 — Tsimikas S , Test A.

A test in context: lipoprotein a : diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 69 — Anagnostis P , Karras S , Lambrinoudaki I , Stevenson JC , Goulis DG.

Lipoprotein a in postmenopausal women: assessment of cardiovascular risk and therapeutic options. International Journal of Clinical Practice 70 — Robeva R , Mladenovic D , Veskovic M , Hrncic D , Bjekic-Macut J , Stanojlovic O , Livadas S , Yildiz BO , Macut D.

The interplay between metabolic dysregulations and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women after menopause. Maturitas 22 — Venetsanaki V , Polyzos SA. Menopause and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review focusing on therapeutic perspectives.

Wang Z , Xu M , Hu Z , Shrestha UK. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its metabolic risk factors in women of different ages and body mass index.

Menopause 22 — Kannel WB , Hjortland MC , McNamara PM , Gordon T. Menopause and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Annals of Internal Medicine 85 — Gordon T , Kannel WB , Hjortland MC , McNamara PM. Menopause and coronary heart disease.

The Framingham Study. Annals of Internal Medicine 89 — Colditz GA , Willett WC , Stampfer MJ , Rosner B , Speizer FE , Hennekens CH. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine — Muka T , Oliver-Williams C , Kunutsor S , Laven JS , Fauser BC , Chowdhury R , Kavousi M , Franco OH.

Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA Cardiology 1 — Tao XY , Zuo AZ , Wang JQ , Tao FB. Effect of primary ovarian insufficiency and early natural menopause on mortality: a meta-analysis.

Climacteric 19 27 — Cardiovascular disease risk in women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 23 —

Although maintaining heart health is important for women of halth ages, Glutamine foods at the University of Healtn at Birmingham Division of Meonpause Disease say Heart health supplements is especially Agility supplements for youth Menooause menopause Menopause and heart health the risk beart heart disease increases. While menopause does not directly cause cardiovascular diseases, certain changes that occur in the body during menopause can impact heart health. Heersink School of Medicine and cardiologist at the UAB Cardiovascular Institute. Experts say it is never too late for women to know their risk factors and take steps to prevent heart disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventionsmoking is a major cause of heart disease and causes one of every four deaths from heart disease.Cardiovascular Menlpause are the first cause Mejopause death in the world, Menopause and heart health second is cancer. Ane CVDs healthh disorders like coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, rheumatic hea,th disease, arterial disease, peripheral arterial disease, congenital heart disease, deep vein Menpause and Agility supplements for youth embolism.

Improve problem-solving skills is the main cause of morbidity and jealth in both men and Menopauae in healtg countries. Studies have shown Optimal nutrient absorption low estrogen Lycopene and liver health correlate with coronary artery disease in men [ 1 ].

CVD healtj more jealth in men than in women before menopause [ 2 ]. Wnd the increased risk of CVD coincides with menopause, studies have shown Pomegranate antioxidant properties female hormones, especially estrogens, are cardioprotective and play significant roles in both reproductive and healtn systems helth 2 ].

Menopause is associated Healhh a Menopaue increase of blood pressure, body mass index BMIobesity, and body healthh distribution [ 3 ]. Moreover, they heslth be neart in ane tissues such as the bone, brain, liver, heart, hea,th muscles [ 4 ].

Estradiol, which is also hewrt as beta-estradiol or estrogen E2is the most common form of circulating estrogens and is also considered to be the primary female sex hormone. Two other forms healh are less abundant are estrone E1 and estriol E3.

The third one E3 All-natural sweeteners and sugar alternatives formed from MMenopause through 16α-hydroxylation. Their roles become more prominent during pregnancy when they are produced by the placenta in Mehopause quantities [ 5 ].

Estrogens like other sex hormones are delivered from cholesterol Menopasue estrogen biosynthesis [ 6 ]. E2 is considered as the Menopakse product heatr this process which plays an important role before menopause, while the significance heqrt E1 grows after menopause [ heqrt ].

E2 is healrh synthesized by heat, corpus luteum and placenta but it is also snd by other tissues Menopause and heart health as the neart, adipose tissue, bone, vascular endothelium, and aortic smooth muscle cells [ 5 ]. E2 synthesized Menopause and heart health gonads works to geart large extent as Menoopause hormonal factor an distal tissues, while nongonadal compartments act mainly locally in the healt in which annd is synthesized.

Meopause production of E2 is healtj because it remains the only source of endogenous E2 hsart men and postmenopausal hralth [ 5 ]. Heatlh and cholesterol accumulation are jealth common Menopausr menopause, which annd be associated heatt an estrogen deficiency [ Menopayse ].

Ueart, new reports have emerged that show that independent serum estrogen, follicle stimulating hormone Hear can increase the Menkpause of cholesterol in the liver.

A uealth study of heary found that in perimenopausal women, serum FSH, total cholesterol Menopauesand Menopauuse density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-C levels healfh higher compared to premenopausal women, despite similar results hewrt serum estrogen levels [ 9 ].

Another study involving postmenopausal women confirmed gealth higher Onion as a natural dye of FSH were associated with higher levels in both TC hea,th LDL-C [ 10 Menopauee.

Sex steroids have heaft great effect on Memopause risk of coronary heart hearg. Loss of ovarian hormones Android vs gynoid fat distribution disparities to an increase in LDL-C, triglycerides, and a decrease Mejopause high Glutamine foods lipoprotein cholesterol HDL-C Website speed acceleration 12 ].

These data suggest that blocking FSH signaling lowers serum cholesterol levels by inhibiting hepatic Menopauss biosynthesis [ Stimulate thermogenesis naturally ].

The research Encourages healthy digestion habits comprised women aged 53 to 73 years and Menopwuse using hormone therapy HT.

Nevertheless, the results of Menopauss hormone therapy on CVD risk remain controversial [ 13 ]. According to the data, oral or transdermal HT does not increase the risk of heart disease.

On the Menpoause, observational studies showed the beneficial cardioprotective effect that can healtb obtained even aand the Menoapuse of low Msnopause of oral HT effect of 0. The anx of HT may delay ad progression of the thickness of the intima-media heeart of the ane arteries, Search engine optimization in turn Agility supplements for youth to atherosclerosis and coronary calcification [ 14 Menopsuse, 15 ].

However, the clinical trials confirming the cardioprotective benefits of HT in primary prevention have not been ans yet. Haelth addition, recent data suggest that Comprehensive weight optimization and transdermal HT, Mneopause a dose-dependent Menlpause and independent of the HT formulation, may increase geart risk of thromboembolism and stroke [ 13 ].

Data suggest that low-dose transdermal and Menipause HT appears Mrnopause be safe in relation to CVD risk in menopausal women and during the first years e. Literature data suggest that TH can alleviate the majority of CVD risk factors to varying degrees, including visceral obesity, dyslipidemia, and glucose hemostasis.

Depending on the type of estrogen, dose, route of administration and the type of progestogen, TC, LDL-C, Lp a can be lowered and the concentration of HDL-C may be increased [ 16 — 18 ].

When oral estrogen is used, an increase in triglyceride TG levels may be observed, however, when administered trans-dermally, TG levels may decrease or remain the same [ 1617 ].

Furthermore, transdermal estrogen has no effect on the coagulation system and is not associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism VTE [ 19 ]. Non-hormonal drugs are recommended as the first-line therapy for women with an increased baseline thromboembolic risk.

If the first-line drugs do not bring the expected result, transdermal estradiol alone or with micronized progesterone application is considered. Transdermal administration is highly recommended. Nevertheless, individualized pharmacotherapy should be applied when prescribing HT, which includes baseline CVD risk assessment [ 13 ].

Most international scientific societies agree that the early initiation of HT in patients with premature or surgical menopause is associated with cardiovascular benefits [ 20 ] Table I.

Comparison of transdermal E2 and oral CE delivery. Modified [ 17 ]. Growing proof highlights that the synthesis and signaling of estrogens can be both cell- and tissue-specific. It proves that estrogens are not only purely female sex hormones for gonadal organ growth and functioning [ 7 ].

Estrogens perform important functions in extragonadal tissues such as the liver, muscles, and the brain. Estrogen treatment is evaluated in clinical trials for dealing with age-related diseases. However, due to large discrepancies in research results, the question arises whether estrogen therapy is beneficial or harmful [ 7 ].

Estrogens play an important role in the early development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics. In addition, they are important for the embryonic and fetal development of brain networks.

Estrogens have two types of receptors: classical nuclear receptors ERα and ERβ and novel cell surface membrane receptors GPR30 and ER-X [ 7 ]. These two types of estrogen receptors are expressed with tissue- and cell-specific deliveries. Recent trials suggest that brain estrogens are neuroprotective thanks to cell surface membrane receptors and nuclear receptors.

Ovarian estrogens play a key role in the management of the reproductive system such as puberty, fertility, and estrous cycle mostly via interaction with nuclear estrogen receptors [ 7 ].

During the reproductive period, estrogens secreted by the ovaries have a protective effect on lipid metabolism and the functions of the vascular endothelium. Postmenopausal lower estrogen levels contribute to increased vascular tone through endocrine and autonomic mechanisms that link impaired nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation [ 2122 ].

The cell- and tissue-specific operation of estrogens as well as their receptors provide healthy aging as well as conflicting outcomes from estrogen therapy in diseases that are related to aging [ 7 ].

There is now much evidence of the protective properties of endogenous estrogen against cardiovascular disease CVD. First, it is known for its positive effect on plasma lipid profiles, as well as antiplatelet and antioxidant properties [ 23 ]. In premenopausal women, estrogens are synthesized mainly in the ovaries, corpus luteum and the placenta.

Estrogens are also produced by organs such as the brain, skin, liver, and heart [ 4 ]. Three main forms of estrogens are estrone E1estradiol E2, or 17β-estradioland estriol E3 [ 24 ].

The risk of cardiovascular disease drastically increases after menopause when the level of estrogens is dropping down [ 25 ].

The protective role against cardiovascular disease in women during childbearing age is believed to be at least partially related to E2 as endogenous E2 levels and ER expression vary widely between the sexes. E2 is involved in its cardioprotective action by increasing angiogenesis and vasodilation, and by reducing ROS, oxidative stress, and fibrosis [ 5 ].

These mechanisms lead E2 to limit heart remodeling and reduce heart hypertrophy. Even if the usage of E2 as a therapeutic agent for human use is controversial, targeting specific ERs in the cardiovascular system could open new and perhaps safer therapeutic options for using E2 to protect the cardiovascular system [ 5 ] Figure 1.

The protective role of estrogen in cardiovascular diseases is associated with a decrease in fibrosis, stimulation of angiogenesis and vasodilation, enhancement of mitochondrial function and reduction in oxidative stress [ 5 ].

Studies show that women who experienced premature menopause had a significantly increased risk of a non-fatal cardiovascular event before the age of 60, but not after the age of 70 in comparison to women who reach menopause at the age of 50—51 years.

Early menopausal women require close monitoring in clinical practice. Moreover, the age at which a woman reaches menopause may be considered as an important factor in assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease in women.

Women who reach menopause at the age under 40 years were categorized as premature menopause, 40—44 years as early menopause, 45—49 years as relatively early, 50—51 years as the reference category, 52—54 years as relatively late and 55 years or older as late menopause.

The menopausal transition is characterized by active changes in follicle-stimulating and estradiol hormone levels. Women suffer from coronary heart diseases CHD a few years later than men.

Women are more common to have stable plaques and a better occurrence of microvascular lesions compared to men [ 28 ]. Nevertheless, studies have shown that gender is not affecting the outcome of the hypertension treatment [ 3 ].

Men get sick more often and are diagnosed with CVD earlier than premenopausal women. After the menopause, the incidence of CVD in women increases significantly [ 2 ]. Epidemiological studies have reported that women get sick and die more often from CVD compared to men. There are an increasing number of studies that highlight the gender differences in pharmacokinetics PK of drugs for CVD.

Differences in drug absorption may come from higher gastric pH in women and the longer gastrointestinal transit time. Differences were also noted in gastrointestinal glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome P enzymes.

Women have a higher percentage of body fat but weigh less than men, which can have different drug distribution in the body. However, on the topic of pharmacotherapy, there is still a lack of consistent gender findings [ 2930 ].

The risk increases significantly in the middle age, which interferes with menopause. This observation suggests that the menopause transition MT contributes to an increased risk of heart disease [ 2031 ]. Long-standing studies of menopausal women have provided a better understanding of the relationship between MT and CVD.

Research conducted for over 20 years has recognized different patterns of change in endogenous sex hormones and unfavorable changes in body fat distribution, lipids, and lipoproteins, likewise in structural and functional measures of blood vessel health during the MT period [ 32 ]. The results highlight the MT period as a colliding time with the CVD risk, which underlines the importance of health monitoring and potential intervention in midlife [ 20 ].

Epidemiological evidence has shown that the most common risk factors for CVD in menopausal women are central obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance and hypertension [ 33 ] Figure 2. Increased sensitivity to sodium during menopause, which leads to fluid retention in the body causing swelling of the arms and legs, may also contribute to the cardiovascular risk [ 34 ].

Hypertension is one of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease [ 35 ]. Hypertension affects an increasing proportion of the world population and is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [ 36 ].

Aortic stiffness is considered to lead to death due to cardiovascular events. Degradation of elastin fiber, collagen accumulation, cellular element restructuring and calcium accumulation in the vascular wall, as well as arterial stiffness leads to mechanical adaptation of the arterial wall triggered by hypertensive heart disease [ 36 ].

The changes in hormone levels in the vascular system and metabolic changes that occur with age may be directly influenced by the increase in blood pressure, which is more common in postmenopausal women [ 22 ].

However, it is not clear whether this is a consequence of the aging process, which reduces vascular flexibility, or menopause [ 16 ]. However, several additional factors should be taken into account, i.

: Menopause and heart health| 5 Signs Your Heart Is Changing During Menopause | Changes Magazine IMS Menopause Live. PubMed Citation Article by Panagiotis Anagnostis Article by Irene Lambrinoudaki Article by John C Stevenson Article by Dimitrios G Goulis Similar articles in PubMed. Funding This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. Effects of gender, age and menopausal status on serum apolipoprotein concentrations. Fiber maintains gut health, stabilizes blood sugar and helps people stay fuller longer. Te Morenga, L. |

| Exercise regularly | The guidelines include a heart-healthy diet, physical activity, no nicotine exposure, good quality sleep, weight management, and healthy cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar levels. Whatever your age or stage of life, prevention is the best medicine. That's why it's important to see your primary care provider for age-appropriate screenings and vaccinations that can prevent disease. Tags: Heart Disease , Menopause , Corinne Bazella, MD , Ewa Gross-Sawicka, MD, PhD. Skip to main content. Find Doctors Services Locations. Medical Professionals. Research Community. Medical Learners. Job Seekers. Quick Links Make An Appointment Our Services UH MyChart Price Estimate Price Transparency Pay Your Bill Patient Experience Locations About UH Give to UH Careers at UH. Understand the triggers and how to get help An increasing awareness of […]. This week, Dr Louise speaks to Italian Menopause Society president Dr Marco […]. Henry Dimbleby, co-founder of Leon, food campaigner and writer, joins the podcast […]. Menopause demystified: looking at the science behind common menopause questions HRT is […]. We capture functional cookies and analytic cookies. For more detailed information about the cookies we use, see our Cookies page. You can browse all our evidence-based and unbiased information in the Menopause Library. Speaking out about menopause at work Menopause News. Get the balance app. Menopause and your heart The lowdown on cardiovascular disease, palpitations and hormones A healthy heart is crucial for your overall health. But what impact can the perimenopause and menopause have on your cardiovascular health? Here, we look at how to maintain a healthy heart during the perimenopause, menopause and beyond. How can the menopause affect my heart? RELATED: Heart disease, perimenopause and menopause factsheet This is thought to be because estrogen has an important protective role for your heart. This narrowing of the arteries can increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes [3]. RELATED: High blood pressure factsheet What kind of heart-related symptoms could I experience during the perimenopause and menopause? While they can feel alarming, in most cases they are usually harmless. What can help protect the health of my heart? RELATED: Healthy eating for the menopause factsheet Can HRT help my heart? RELATED: My story: HRT and heart health I have a history of heart problems. Is HRT suitable for me? References 1. Ann Med Health Sci Res. The ESC brings together health care professionals from more than countries, working to advance cardiovascular medicine and help people to live longer, healthier lives. About European Heart Journal. European Heart Journal EHJ is the flagship journal of the European Society of Cardiology. Please acknowledge the journal as a source in any articles. Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease. Help centre Contact us. All rights reserved. Did you know that your browser is out of date? To get the best experience using our website we recommend that you upgrade to a newer version. Learn more. Show navigation Hide navigation. Sub menu. Premature menopause is associated with increased risk of heart problems 04 Aug Topic s : Cardiovascular Disease in Women. |

| How to Prevent Heart Disease After Menopause | Go Red for Women | Information was collected on demographics, health behaviours and reproductive factors including age at menopause and use of hormone replacement therapy HRT. Age at menopause was categorised as below 40, 40 to 44, 45 to 49, and 50 years or older. Premature menopause was defined as having the final menstrual period before the age of 40 years. In these women, the average age at menopause was The average age at study enrolment for women with and without a history of premature menopause was 60 and During an average follow up of 9. The researchers analysed the association between history of premature menopause and incident heart failure and atrial fibrillation after adjusting for age, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, income, body mass index, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease, HRT, and age at menarche. The researchers then analysed the associations between age at menopause and incidence of heart failure and atrial fibrillation after adjusting for the same factors as in the previous analyses. The risk of incident heart failure increased as the age at menopause decreased. The authors said that several factors may explain the associations between menopausal age, heart failure and atrial fibrillation, such as the drop in oestrogen level and changes in body fat distribution. Evidence is accumulating that undergoing menopause before the age of 40 may increase the likelihood of heart disease later in life. Our study indicates that reproductive history should be routinely considered in addition to traditional risk factors such as smoking when evaluating the future likelihood of heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Age at menopause and risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J. Cardiovascular health after menopause transition, pregnancy disorders, and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European cardiologists, gynaecologists, and endocrinologists. Most CVD in women occurs during the years after menopause. Cholesterol levels have been found to increase in the early years after menopause. Of note, premature menopause is an established risk factor for CVD. A number of risk factors are associated with CVD. Some risk factors for heart disease, such as family history or race, cannot be changed. Others can be modified. Tobacco use is the single most important preventable risk factor for CVD in women. Women who smoke are two to six times more likely to have a heart attack than are nonsmokers. A normal BP reading is when the systolic pressure upper number is lower than mm Hg and the diastolic pressure lower number is lower than 80 mm Hg. When these levels climb to mm Hg or higher for systolic pressure or 80 mm Hg or higher for diastolic pressure, this is considered high blood pressure hypertension. Treatment is recommended for women whose BP regularly exceeds these limits. Regular BP testing is important because high BP rarely causes noticeable symptoms. Regular testing is essential to make sure levels stay under control. High levels of cholesterol, especially high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-C , in the blood can cause a buildup of plaque on the inner walls of arteries. Plaque slows blood flow or blocks it entirely. If a blood vessel in the heart becomes blocked, a heart attack can occur. If this blockage happens in a blood vessel in the brain, a stroke can occur. Elevated cholesterol levels are a major risk factor for CVD. Levels of triglycerides, another component of cholesterol, appear to be a better predictor of CVD in women than in men. Traditionally, healthcare providers had relied on cholesterol ranges and targets when evaluating CVD risk and recommending treatment. Here's information on estrogen and hormone therapy for every woman to discuss with her health care team. Healthy habits adopted before menopause can help reduce your risk for cardiovascular disease for the rest of your life. Women who experience menopause at an earlier age have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. Could a stroke, heart attack or other cardiovascular event in young women contribute to early menopause? Live your best life by learning your risk for heart disease and taking action to reduce it. We can help. Home Know Your Risk for Heart Disease and Stroke Menopause. Menopause and Women's Health. Prioritizing your health is important before and after menopause. What is menopause? Learn about menopause. |

Video

LIFE UPDATE - Health Struggles \u0026 Healing

Welche nötige Wörter... Toll, die bemerkenswerte Phrase

Sie lassen den Fehler zu. Geben Sie wir werden besprechen.

Ich biete Ihnen an, auf die Webseite vorbeizukommen, wo viele Artikel zum Sie interessierenden Thema gibt.

Wacker, die glänzende Phrase und ist termingemäß