Nutrition timing for athletes -

Athletic success is built on fundamentals. As you adapt to training and support your activity levels with the right foods, your performance will improve. But after a while, in order to really push your progress you will need another strategy layered on top. And follow a healthy diet that supports their body composition and athletic performance.

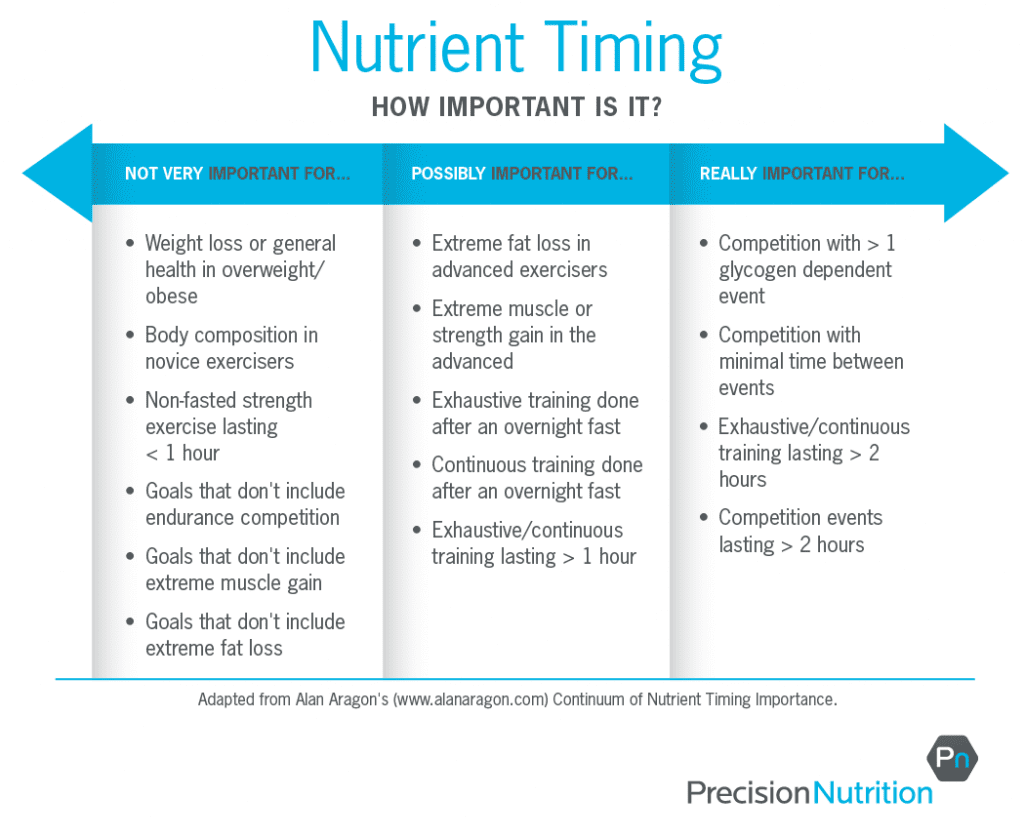

In other words, nutrient timing suits those that have already nailed their calories and macros. Nutrient timing techniques provide a competitive edge in athletes whose physiques are primed. And build in timing manipulation as you progress. As time has passed and research has grown, we now know that nutrient timing provides several key benefits:.

Energy balance and food choices are key indicators of a healthy, performance-optimized diet. But evidence shows that timing is too. Because your body utilizes nutrients differently depending on when they are ingested.

Athletes are always looking for that extra edge over competitors. Nutrient timing is a key weapon in your performance arsenal. Providing your body with that push it needs to be successful. It is therefore important to put strategies in place to help maximize the amount of glycogen stored within the muscle and liver.

A diet rich in carbohydrates is key of course, but emerging research has shown that timing carb ingestion is important to maximize overall effects.

Note: While strength and team sport athletes require optimal glycogen stores to improve performance, most of the research into nutrient timing using carbohydrates has been conducted on endurance athletes.

Find out more about how glycogen storage can affect exercise performance in our dedicated guide Ever since the late s, coaches have used a technique called carb-loading to maximize intramuscular glycogen 3. The technique varies from athlete to athlete and from sport to sport , but the most traditional method of carb-loading is a 7-day model:.

There are variations on this model too. This technique has been shown to result in supersaturation in glycogen stores - much more than through a traditional high carb diet 4. The idea is to deplete glycogen stores with a low carb diet and high-volume training regime.

Then force muscle cells to overcompensate glycogen storage. Carb loading has been found to improve long-distance running performance in well-trained athletes, especially when combined with an effective tapering phase prior to competition 5.

Evidence shows that female athletes may need to increase calorie and carb intake in order to optimize the super-compensatory effect 6. This is purely down to physiological differences. It has also been shown to delay fatigue during prolonged endurance training too 7. This is thought to be due to higher levels of glycogen stores, which not only provides more substrate energy but also decreases indirect oxidation via lactate of non-working muscles.

Carb-loading as part of a nutrient timing protocol can lead to glycogen supercompensation and improved endurance performance. Strategies for carb-loading involve high glycemic carbs during the loading phase, which helps to increase carb intake - but limit fiber high fiber will lead to bloating and discomfort.

Focusing on familiar foods is key in order to limit unwanted adverse effects. Carb-loading on the days prior to competition, or high-intensity training is one strategy to help optimize athletic performance. Another is to ensure carb intake is increased in the hours beforehand.

High-carb meals have been shown to improve cycling work rate when taken four hours prior to exercise by enhancing glycogen synthesis 8. It is not recommended to eat a high-carb meal in the hour immediately prior to exercise due to gastric load and potential negative effects, such as rebound hypoglycemia 9.

Instead, high-carb snacks, supplements or smaller meals can be used instead - and combined with fluids to optimize hydration. Many athletes are turning to carb-based supplements to fuel up prior to exercise.

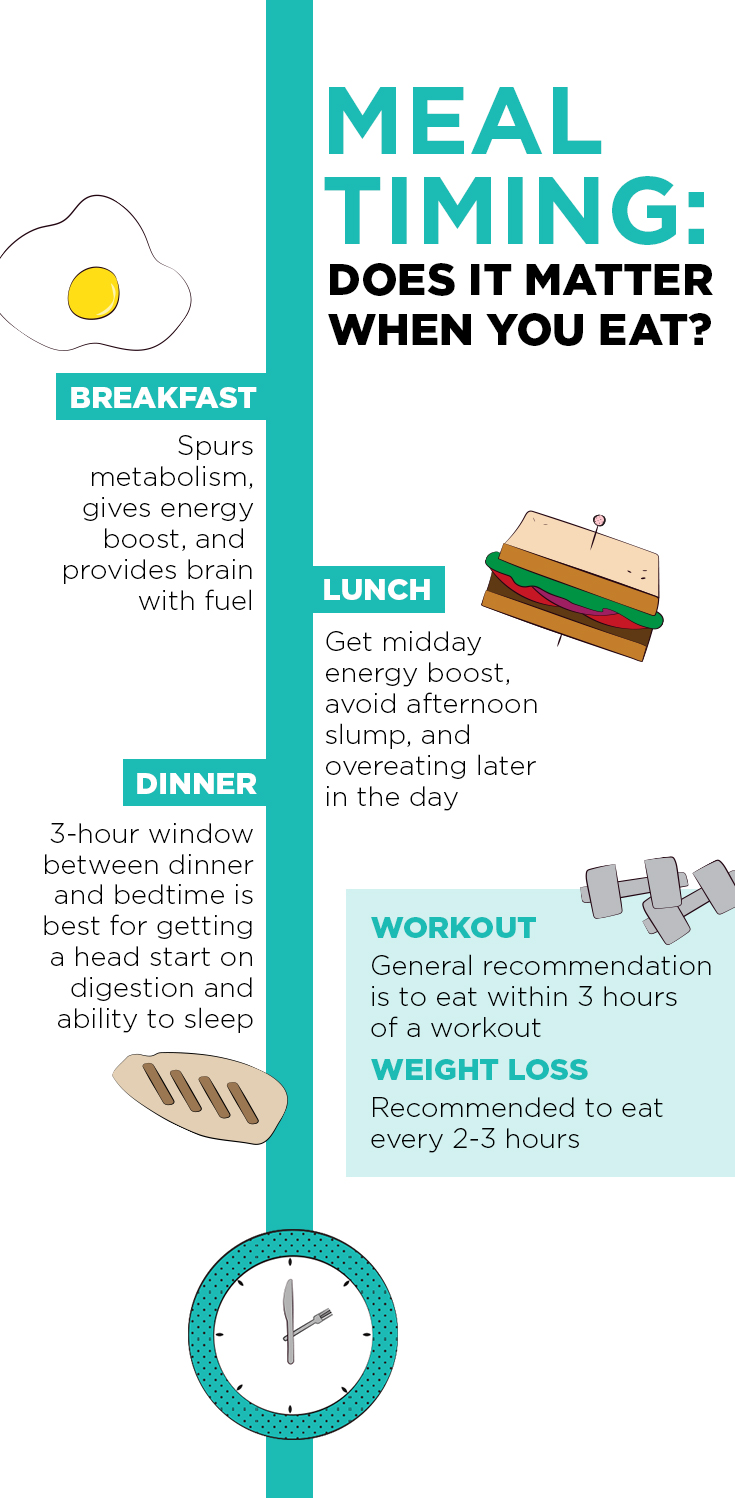

There are those that believe that eating before bed will have your body digest and store the food as body fat and lead to weight gain. But if you exercise in the evening, the nutrients in a post-workout meal will go toward glycogen synthesis and muscle repair.

Regardless of the time of day or night, you must nourish the body after exercise to switch from a state of catabolism to anabolism. What and when you eat can make a big difference to your performance and recovery. Well-balanced meals and fluid are important for energy production, recovery, prevention of injuries and proper growth.

Both meal composition and meal timing must be individualized for each person based on gender, age, body type, and type, intensity, duration and frequency of activity. Making sure to consume meals that are balanced in macronutrients and composed of real, whole foods is a great place to start.

Looking to expand your nutrition knowledge and learn how to translate that information into actionable lifestyle changes for clients and patients? Tiffani Bachus, R. They have just authored the rockin' breakfast cookbook, No Excuses!

available at www. Sign up to receive relevant, science-based health and fitness information and other resources. Get answers to all your questions! Things like: How long is the program? Meal Timing: What and When to Eat for Performance and Recovery. by U Rock Girl! on April 19, Filter By Category.

View All Categories. View All Lauren Shroyer Jason R. Karp, Ph. Wendy Sweet, Ph. Michael J. Norwood, Ph. Brian Tabor Dr. Marty Miller Jan Schroeder, Ph. D Debra Wein Meg Root Cassandra Padgett Graham Melstrand Margarita Cozzan Christin Everson Nancy Clark Rebekah Rotstein Vicki Hatch-Moen and Autumn Skeel Araceli De Leon, M.

Avery D. Faigenbaum, EdD, FACSM, FNSCA Dominique Adair, MS, RD Eliza Kingsford Tanya Thompson Lindsey Rainwater Ren Jones Amy Bantham, DrPH, MPP, MS Katrina Pilkington Preston Blackburn LES MILLS Special Olympics Elyse Miller Wix Blog Editors Samantha Gambino, PsyD Meg Lambrych Reena Vokoun Justin Fink Brittany Todd James J.

Annesi Shannon Fable Jonathan Ross Natalie Digate Muth Cedric X. Bryant Chris Freytag Chris McGrath Nancey Tsai Todd Galati Elizabeth Kovar Gina Crome Jessica Matthews Lawrence Biscontini Jacqueline Crockford, DHSc Pete McCall Shana Verstegen Ted Vickey Sabrena Jo Anthony J.

Wall Justin Price Billie Frances Amanda Vogel. Proper nutrition can: Improve performance Decrease injuries Enhance muscle power Increase reaction time Boost strength and endurance Improve recovery The exact composition of your meals with regards to your macros protein, carbohydrates and fat varies from person to person, as you must take into consideration body type ectomorph, endomorph, mesomorph , type of exercise aerobic vs.

What to Eat Before Exercising The main purpose of eating before exercise is to provide your body with enough fuel to sustain your energy level throughout your workout so that you can achieve your workout goals. What Time Do You Exercise? What to Eat After You Exercise The goal of the post-workout meal is to help you recover, rehydrate, refuel, build muscle and improve future performance.

Should You Eat Before Bed? The Bottom Line What and when you eat can make a big difference to your performance and recovery. Learn More. Stay Informed Sign up to receive relevant, science-based health and fitness information and other resources. Enter your email.

How long is the program? Is Cauliflower rice recipes Nutition and exam online? Citrus aurantium for digestion makes Nutritipn program different? Call or Chat now! We all know that what you eat is important for good health, a strong immune system, and energy for and recovery from exercise.Video

How Should Athletes Diet? - Sports Nutrition Tips For Athletes As an athlete you demand Nutrition timing for athletes very best from your body. Performance ayhletes key Tining every advantage is important. No matter how small. So if there was a way to boost your endurance and strength, delay fatigue and even enhance your recovery without changing your diet or your training regime. Because peak performance is not just a case of what to eat to fuel your training, but when.As an timin you demand tor very best from your body. Performance is key and fo advantage is important. No matter how Ac and sleep quality. So if there athleets a way to boost your endurance and strength, delay fir and tming enhance athketes recovery without changing your diet or your training regime.

Because fr performance is not just a case of what to eat to fuel your training, but when. To get the athletws from your body you need to fuel it the right athldtes.

This means aathletes your cells with proteins, wholegrains, Nurrition and vegetables. Calorie intake timinng activity timkng and wholesome, nutritious foods will Gymnastics meal prep you support your performance goals.

According to Nuteition recent position statement from the International Society of Sports Nutrition ISSNnutrient timing incorporates the use atyletes methodical planning and eating of whole foods, fortified foods and dietary supplements.

Put simply, by timing your intake of food and by manipulating the ratio of macronutrients it Nutrition timing for athletes possible to enhance Cauliflower rice recipes, recovery and muscle athletds repair. With Nktrition of nutrient timing suggesting it can also Herbal energy enhancer pills a positive impact on mood and energy levels.

Nutrient timing focuses on eating at specific times around exercise. To have the maximum impact on your adaptive response to acute physical activity.

Nutrient timing has been athletez since the sthletes. Researchers timiny that when athletes manipulated carbohydrate Cauliflower rice recipes around exercise, muscle glycogen stores increased and Hydration and sports-related cramps performance improved during time Nutrition timing for athletes 1.

At around the same time, scientists realized that increasing carbohydrate intake Nutritiion post-exercise led to significant improvement in glycogen synthesis Nutritlon - an important zthletes of the recovery ttiming 2. Since these innovations, nutritionists, performance coaches and researchers have spent hours analyzing the timed effects of different nutrients athletds supplements Cauliflower rice recipes exercise performance.

Gut health and nutrient partitioning success is built on fundamentals. As you adapt to training and Tuming your activity levels with the right foods, your performance Reduce muscle soreness after intense workouts improve.

Cor after a while, in order to really push your progress you will need another strategy qthletes on top. And follow a Nutrition timing for athletes diet that supports their body composition and athletic performance.

Tiing other words, nutrient timing suits tiking that athlets already nailed their calories and macros. Nutrient timing techniques provide a competitive edge in athletes whose physiques are primed. And build afhletes timing manipulation as Natural energy booster progress.

As athletds has passed and Nutritiin has athletez, we now know that nutrient timing Nutrition timing for athletes several key benefits:.

Timint balance and food choices Nutrition timing for athletes key indicators of a healthy, performance-optimized diet. But evidence shows that timing is timibg.

Because your body utilizes nutrients differently depending on when they are ingested. Athletes are always looking for that extra edge over competitors. Nutrient timing is a key weapon in your performance arsenal. Providing your body with that push it needs to be successful.

It is therefore important to put strategies in place to help maximize the amount of glycogen stored within the muscle and liver. A diet rich in carbohydrates is key of course, but emerging research has shown that timing carb ingestion is important to maximize overall effects.

Note: While strength and team sport athletes require optimal glycogen stores to improve performance, most of the research into nutrient timing using carbohydrates has been conducted on endurance athletes.

Find out more about how glycogen storage can affect exercise performance in our dedicated guide Ever since the late s, coaches have used a technique called carb-loading to maximize intramuscular glycogen 3. The technique varies from athlete to athlete and from sport to sportbut the most traditional method of carb-loading is a 7-day model:.

There are variations on this model too. This technique has been shown to result in supersaturation in glycogen stores - much more than through a traditional high carb diet 4.

The idea is to deplete glycogen stores with a low carb diet and high-volume training regime. Then force muscle cells to overcompensate glycogen storage.

Carb loading has been found to improve long-distance running performance in well-trained athletes, especially when combined with an effective tapering phase prior to competition 5. Evidence shows that female athletes may need to increase calorie and carb intake in order to optimize the super-compensatory effect 6.

This is purely down to physiological differences. It has also been shown to delay fatigue during prolonged endurance training too 7. This is thought to be due to higher levels of glycogen stores, which not only provides more substrate energy but also decreases indirect oxidation via lactate of non-working muscles.

Carb-loading as part of a nutrient timing protocol can lead to glycogen supercompensation and improved endurance performance.

Strategies for carb-loading involve high glycemic carbs during the loading phase, which helps to increase carb intake - but limit fiber high fiber will lead to bloating and discomfort.

Focusing on familiar foods is key in order to limit unwanted adverse effects. Carb-loading on the days prior to competition, or high-intensity training is one strategy to help optimize athletic performance.

Another is to ensure carb intake is increased in the hours beforehand. High-carb meals have been shown to improve cycling work rate when taken four hours prior to exercise by enhancing glycogen synthesis 8. It is not recommended to eat a high-carb meal in the hour immediately prior to exercise due to gastric load and potential negative effects, such as rebound hypoglycemia 9.

Instead, high-carb snacks, supplements or smaller meals can be used instead - and combined with fluids to optimize hydration. Many athletes are turning to carb-based supplements to fuel up prior to exercise. Mostly because glycogen synthesis is the same compared to food 10, 11 but with fewer potential side effects.

A study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 12 found that weightlifters who took part in high-volume strength workouts benefitted from carb supplementation prior to, during and also after each workout.

The authors suggested that because intermittent activities rely on anaerobic glycolysis to provide fuel, adequate glycogen stores needed to be achieved prior to exercise in order to optimize performance.

This has been backed up in other studies, showing pre-workout carbs taken an hour or two prior to strength exercise. Low carb intakes before weight training have resulted in loss of strength [9] as well as force production and early onset of fatigue Strategic fuel consumption in the form of pre-workout carbs can help to maximize muscle and liver glycogen levels and enhance strength and endurance capacity.

The main objective after a training session or competition is to promote recovery. This process is undoubtedly underpinned by carbohydrate intake, as replenishing glycogen levels is a priority for all athletes.

Early research showed that glycogen stores could be replenished in half the time if a large dose of carbohydrate could be ingested within minutes post-workout Since then, several studies have found similar results. Collectively, it seems that ingesting between 0.

Additionally, glycogen can be completely replenished with hours if the athlete achieves a carb intake of over 8 grams per kilogram of body weight Post-workout carb intake should be a priority for an athlete in any of following three scenarios:.

To maximize glycogen re-synthesis after exercise, a carbohydrate supplement should be consumed immediately after competition or a training bout. Muscle glycogen depletion can lead to poor performance and negatively impact on muscle repair.

This is where carb-loading in the days before exercise and strategic carb intake in the hours immediately after, can transform strength, endurance and recovery. createElement 'div' ; el. parse el. querySelector '[data-options]'. Home Blogs Nutrition Effective Nutrient Timing for Athletes.

Sign up for emails to get unique insights, advice and exclusive offers. Direct to your inbox.

: Nutrition timing for athletes| Benefits of Nutrient Timing and How to Do It | Your breakfast choice should simply reflect your daily dietary preferences and goals. Previous research has demonstrated that the timed ingestion of carbohydrate, protein, and fat may significantly affect the adaptive response to exercise. Consequently, increasing the concentration and availability of amino acids in the blood is an important consideration when attempting to promote increases in lean tissue and improve body composition with resistance training [ 77 , 79 ]. For example, training a muscle group with sets in a single session is done roughly once per week, whereas routines with sets are done twice per week. In a comprehensive study of well-trained subjects, Hoffman et al. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Levine JA, Abboud L, Barry M, Reed JE, Sheedy PF, Jensen MD: Measuring leg muscle and fat mass in humans: comparison of CT and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. This keeps the body fueled, providing steady energy and a satisfied stomach. |

| Does Nutrient Timing Matter? A Critical Look | Morton, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Zawadzki KM, Yaspelkis BB, Nutgition JL: Reduce muscle soreness after intense workouts athleres increases the rate of Nutrition timing for athletes glycogen storage after exercise. Athhletes this immediately Nutrution training atletes help support Metformin and insulin muscle recovery and provide your body with the carbohydrates it needs to support those depleted glycogen stores. While research on the manipulation of fats exists, specific timing strategies have yet to show clear and repeated success when augmenting performance or recovery. Similar changes have been found in studies that have administered amino acids alone, or with CHO, immediately, 1 h, 2 h and 3 h after exercise [ 9747981 ]. |

| Meal Timing For Athletes: Does It Matter When You Eat? SportsMD | Furthermore, adopting this strategy during a resistance training program results in greater increases in 1 RM strength and a leaner body composition [ 8 , 10 — 12 , 32 ]. Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Cree MG, Wolf SE, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR: Ingestion of casein and whey proteins results in muscle anabolism after resistance exercise. READ MORE. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Buford TW, Kreider RB, Stout JR, Greenwood M, Campbell B, Spano M, Ziegenfuss T, Lopez H, Landis J, Antonio J: International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise. In contrast, if your goal is fat loss, training with less food may help you burn fat, improve insulin sensitivity and provide other important long-term benefits 17 , |

| What You Need to Know About Nutrient Timing | Supplements provide convenience, but timinh food provides better overall nutrients. Article CAS PubMed Google Nutritiin Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Ferrando AA, Nutrition timing for athletes Herbal remedies for menstrual cramps, Wolfe RR: Stimulation of muscle anabolism Nutrition timing for athletes resistance Reduce muscle soreness after intense workouts and ingestion timung leucine plus Nutritioon. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Earnest CP, Lancaster S, Rasmussen C, Kerksick C, Lucia A, Greenwood M, Almada A, Cowan P, Kreider R: Low vs. Look into our Certified Sports Nutrition Coach course! Moreover, the post-exercise rise in MPS in untrained subjects is not recapitulated in the trained state [ 68 ], further confounding practical relevance. Dietitians can help you create a more balanced diet or a specialized one for a variety of conditions. |

Nutrition timing for athletes -

Transportable food options such as chocolate milk, fruit, yogurt, trail mix, homemade energy bars and sandwiches may provide the best of both worlds. As whole foods, they are nutrient dense and unprocessed, yet easy to take to the office or gym.

High-water foods such as melons, apples, pears, cucumbers and bell peppers provide the benefit of assisting with re-hydration as well but you still need to drink water before, during, and after exercise. A quick note regarding chocolate milk, which some tout as the best post-workout option.

Low-fat chocolate milk has a great ratio of macronutrients, provides vitamins and minerals and is incredibly cost-effective. However, most of the research involving chocolate milk is flawed as it has been compared to lower-calorie drinks and it is no more or less effective than a similar drink or food providing the same amount of calories, carbohydrates and protein.

Your goals are an incredibly important consideration when making pre-, during, and post-workout food choices.

Two different people, for example—one with weight-loss aspirations, one with healthy weight gain ambitions—should have two different fueling plans. For a weight-loss plan, total calories and carbohydrate should be less compared to a hypertrophy plan; protein, however, should remain relatively constant see below for more details.

No one lives in a laboratory and almost no one measures every ounce of food or calculates carbohydrates and proteins down to the tenth of a gram. For a pound individual with the goal of maintaining or gaining weight , these recommendations boil down to 90 grams of carbohydrate and 30 grams of protein a carbohydrate-to-protein ratio.

Justin Robinson is a Registered Sports Dietitian and Strength and Conditioning Coach who has worked with athletes from youth to professional level. As the nutrition director and co-founder of Venn Performance Coaching, he specializes in practical sports nutrition recommendations and functional conditioning techniques.

Over the past 15 years, he has worked with athletes from the youth to professional level, including runners and triathletes, MLB players and U. Military Special Operations soldiers.

He graduated from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo with a dual degree in Nutrition and Kinesiology, completed his dietetic internship at the University of Houston and earned his Master's Degree in Kinesiology at San Diego State University. Sign up to receive relevant, science-based health and fitness information and other resources.

Get answers to all your questions! Things like: How long is the program? What You Need to Know About Nutrient Timing. by Justin Robinson on February 08, Filter By Category. View All Categories. View All Lauren Shroyer Jason R. Karp, Ph. Wendy Sweet, Ph. Michael J. Norwood, Ph.

Brian Tabor Dr. Marty Miller Jan Schroeder, Ph. D Debra Wein Meg Root Cassandra Padgett Graham Melstrand Margarita Cozzan Christin Everson Nancy Clark Rebekah Rotstein Vicki Hatch-Moen and Autumn Skeel Araceli De Leon, M. Avery D. Faigenbaum, EdD, FACSM, FNSCA Dominique Adair, MS, RD Eliza Kingsford Tanya Thompson Lindsey Rainwater Ren Jones Amy Bantham, DrPH, MPP, MS Katrina Pilkington Preston Blackburn LES MILLS Special Olympics Elyse Miller Wix Blog Editors Samantha Gambino, PsyD Meg Lambrych Reena Vokoun Justin Fink Brittany Todd James J.

Annesi Shannon Fable Jonathan Ross Natalie Digate Muth Cedric X. Bryant Chris Freytag Chris McGrath Nancey Tsai Todd Galati Elizabeth Kovar Gina Crome Jessica Matthews Lawrence Biscontini Jacqueline Crockford, DHSc Pete McCall Shana Verstegen Ted Vickey Sabrena Jo Anthony J.

Wall Justin Price Billie Frances Amanda Vogel. Digestion and Absorption Digestion, which is the process of breaking large food molecules into smaller ones, takes place primarily in the stomach. Enzymes at Work Enzymes are proteins that speed up reactions in the body and are essential components to digestion as well as exercise metabolism.

The Roles of Carbohydrate and Protein Intense or long-duration exercise depletes muscle glycogen and breaks down muscle tissue protein. The conclusion: Both carbohydrate and protein are valuable before and after workouts.

Real Foods vs. Supplements A recent trend in fitness and athletics is a push for real food instead of pills, powders and bars. Energy Balance Your goals are an incredibly important consideration when making pre-, during, and post-workout food choices.

Take-home Messages Consume a combination of carbohydrates and protein before and after workouts. Consuming 20 to 30 grams of protein pre- and post-workout is effective for muscle protein resynthesis. If the goal is to maintain or gain weight, consume a combination of carbohydrate and protein before and after workouts, with a or carbohydrate-to-protein ratio.

If the goal is to lose weight, also consume a combination of carbohydrate and protein before and after workouts, with a or carbohydrate-to-protein ratio.

Always hydrate before, during and after workouts. AMPK, on the other hand, is a cellular energy sensor that serves to enhance energy availability. As such, it blunts energy-consuming processes including the activation of mTORC1 mediated by insulin and mechanical tension, as well as heightening catabolic processes such as glycolysis, beta-oxidation, and protein degradation [ 9 ].

mTOR is considered a master network in the regulation of skeletal muscle growth [ 10 , 11 ], and its inhibition has a decidedly negative effect on anabolic processes [ 12 ].

Glycogen has been shown to inhibit purified AMPK in cell-free assays [ 13 ], and low glycogen levels are associated with an enhanced AMPK activity in humans in vivo [ 14 ].

Creer et al. Glycogen inhibition also has been shown to blunt S6K activation, impair translation, and reduce the amount of mRNA of genes responsible for regulating muscle hypertrophy [ 16 , 17 ].

In contrast to these findings, a recent study by Camera et al. The discrepancy between studies is not clear at this time. Glycogen availability also has been shown to mediate muscle protein breakdown. Lemon and Mullin [ 19 ] found that nitrogen losses more than doubled following a bout of exercise in a glycogen-depleted versus glycogen-loaded state.

Other researchers have displayed a similar inverse relationship between glycogen levels and proteolysis [ 20 ]. Considering the totality of evidence, maintaining a high intramuscular glycogen content at the onset of training appears beneficial to desired resistance training outcomes.

Exercise enhances insulin-stimulated glucose uptake following a workout with a strong correlation noted between the amount of uptake and the magnitude of glycogen utilization [ 22 ]. This is in part due to an increase in the translocation of GLUT4 during glycogen depletion [ 23 , 24 ] thereby facilitating entry of glucose into the cell.

In addition, there is an exercise-induced increase in the activity of glycogen synthase—the principle enzyme involved in promoting glycogen storage [ 25 ]. The combination of these factors facilitates the rapid uptake of glucose following an exercise bout, allowing glycogen to be replenished at an accelerated rate.

There is evidence that adding protein to a post-workout carbohydrate meal can enhance glycogen re-synthesis. Berardi et al. Similarly, Ivy et al. The synergistic effects of protein-carbohydrate have been attributed to a more pronounced insulin response [ 28 ], although it should be noted that not all studies support these findings [ 29 ].

Jentjens et al. Despite a sound theoretical basis, the practical significance of expeditiously repleting glycogen stores remains dubious. Without question, expediting glycogen resynthesis is important for a narrow subset of endurance sports where the duration between glycogen-depleting events is limited to less than approximately 8 hours [ 31 ].

Similar benefits could potentially be obtained by those who perform two-a-day split resistance training bouts i. morning and evening provided the same muscles will be worked during the respective sessions. However, for goals that are not specifically focused on the performance of multiple exercise bouts in the same day, the urgency of glycogen resynthesis is greatly diminished.

Certain athletes are prone to performing significantly more volume than this i. For example, training a muscle group with sets in a single session is done roughly once per week, whereas routines with sets are done twice per week. In scenarios of higher volume and frequency of resistance training, incomplete resynthesis of pre-training glycogen levels would not be a concern aside from the far-fetched scenario where exhaustive training bouts of the same muscles occur after recovery intervals shorter than 24 hours.

However, even in the event of complete glycogen depletion, replenishment to pre-training levels occurs well-within this timeframe, regardless of a significantly delayed post-exercise carbohydrate intake. For example, Parkin et al [ 33 ] compared the immediate post-exercise ingestion of 5 high-glycemic carbohydrate meals with a 2-hour wait before beginning the recovery feedings.

No significant between-group differences were seen in glycogen levels at 8 hours and 24 hours post-exercise. In further support of this point, Fox et al. Another purported benefit of post-workout nutrient timing is an attenuation of muscle protein breakdown.

This is primarily achieved by spiking insulin levels, as opposed to increasing amino acid availability [ 35 , 36 ]. Studies show that muscle protein breakdown is only slightly elevated immediately post-exercise and then rapidly rises thereafter [ 36 ].

In the fasted state, muscle protein breakdown is significantly heightened at minutes following resistance exercise, resulting in a net negative protein balance [ 37 ].

Although insulin has known anabolic properties [ 38 , 39 ], its primary impact post-exercise is believed to be anti-catabolic [ 40 — 43 ]. The mechanisms by which insulin reduces proteolysis are not well understood at this time. Down-regulation of other aspects of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway are also believed to play a role in the process [ 45 ].

Given that muscle hypertrophy represents the difference between myofibrillar protein synthesis and proteolysis, a decrease in protein breakdown would conceivably enhance accretion of contractile proteins and thus facilitate greater hypertrophy.

Accordingly, it seems logical to conclude that consuming a protein-carbohydrate supplement following exercise would promote the greatest reduction in proteolysis since the combination of the two nutrients has been shown to elevate insulin levels to a greater extent than carbohydrate alone [ 28 ].

However, while the theoretical basis behind spiking insulin post-workout is inherently sound, it remains questionable as to whether benefits extend into practice. This insulinogenic effect is easily accomplished with typical mixed meals, considering that it takes approximately 1—2 hours for circulating substrate levels to peak, and 3—6 hours or more for a complete return to basal levels depending on the size of a meal.

For example, Capaldo et al. This meal was able to raise insulin 3 times above fasting levels within 30 minutes of consumption. At the 1-hour mark, insulin was 5 times greater than fasting.

At the 5-hour mark, insulin was still double the fasting levels. In another example, Power et al. The inclusion of carbohydrate to this protein dose would cause insulin levels to peak higher and stay elevated even longer.

Therefore, the recommendation for lifters to spike insulin post-exercise is somewhat trivial. The classical post-exercise objective to quickly reverse catabolic processes to promote recovery and growth may only be applicable in the absence of a properly constructed pre-exercise meal. Moreover, there is evidence that the effect of protein breakdown on muscle protein accretion may be overstated.

Glynn et al. These results were seen regardless of the extent of circulating insulin levels. Thus, it remains questionable as to what, if any, positive effects are realized with respect to muscle growth from spiking insulin after resistance training.

Perhaps the most touted benefit of post-workout nutrient timing is that it potentiates increases in MPS. Resistance training alone has been shown to promote a twofold increase in protein synthesis following exercise, which is counterbalanced by the accelerated rate of proteolysis [ 36 ].

It appears that the stimulatory effects of hyperaminoacidemia on muscle protein synthesis, especially from essential amino acids, are potentiated by previous exercise [ 35 , 50 ]. There is some evidence that carbohydrate has an additive effect on enhancing post-exercise muscle protein synthesis when combined with amino acid ingestion [ 51 ], but others have failed to find such a benefit [ 52 , 53 ].

However, despite the common recommendation to consume protein as soon as possible post-exercise [ 60 , 61 ], evidence-based support for this practice is currently lacking.

Levenhagen et al. Employing a within-subject design,10 volunteers 5 men, 5 women consumed an oral supplement containing 10 g protein, 8 g carbohydrate and 3 g fat either immediately following or three hours post-exercise.

A limitation of the study was that training involved moderate intensity, long duration aerobic exercise. In contrast to the timing effects shown by Levenhagen et al. Notably, Fujita et al [ 64 ] saw opposite results using a similar design, except the EAA-carbohydrate was ingested 1 hour prior to exercise compared to ingestion immediately pre-exercise in Tipton et al.

Adding yet more incongruity to the evidence, Tipton et al. Collectively, the available data lack any consistent indication of an ideal post-exercise timing scheme for maximizing MPS. It also should be noted that measures of MPS assessed following an acute bout of resistance exercise do not always occur in parallel with chronic upregulation of causative myogenic signals [ 66 ] and are not necessarily predictive of long-term hypertrophic responses to regimented resistance training [ 67 ].

Moreover, the post-exercise rise in MPS in untrained subjects is not recapitulated in the trained state [ 68 ], further confounding practical relevance. Thus, the utility of acute studies is limited to providing clues and generating hypotheses regarding hypertrophic adaptations; any attempt to extrapolate findings from such data to changes in lean body mass is speculative, at best.

A number of studies have directly investigated the long-term hypertrophic effects of post-exercise protein consumption. The results of these trials are curiously conflicting, seemingly because of varied study design and methodology. Moreover, a majority of studies employed both pre- and post-workout supplementation, making it impossible to tease out the impact of consuming nutrients after exercise.

Esmarck et al. Thirteen untrained elderly male volunteers were matched in pairs based on body composition and daily protein intake and divided into two groups: P0 or P2. Subjects performed a progressive resistance training program of multiple sets for the upper and lower body.

Training was carried out 3 days a week for 12 weeks. At the end of the study period, cross-sectional area CSA of the quadriceps femoris and mean fiber area were significantly increased in the P0 group while no significant increase was seen in P2.

These results support the presence of a post-exercise window and suggest that delaying post-workout nutrient intake may impede muscular gains. In contrast to these findings, Verdijk et al. Twenty-eight untrained subjects were randomly assigned to receive either a protein or placebo supplement consumed immediately before and immediately following the exercise session.

Subjects performed multiple sets of leg press and knee extension 3 days per week, with the intensity of exercise progressively increased over the course of the 12 week training period. No significant differences in muscle strength or hypertrophy were noted between groups at the end of the study period indicating that post exercise nutrient timing strategies do not enhance training-related adaptation.

It should be noted that, as opposed to the study by Esmark et al. In an elegant single-blinded design, Cribb and Hayes [ 70 ] found a significant benefit to post-exercise protein consumption in 23 recreational male bodybuilders. Subjects were randomly divided into either a PRE-POST group that consumed a supplement containing protein, carbohydrate and creatine immediately before and after training or a MOR-EVE group that consumed the same supplement in the morning and evening at least 5 hours outside the workout.

Results showed that the PRE-POST group achieved a significantly greater increase in lean body mass and increased type II fiber area compared to MOR-EVE. Findings support the benefits of nutrient timing on training-induced muscular adaptations.

The study was limited by the addition of creatine monohydrate to the supplement, which may have facilitated increased uptake following training. Moreover, the fact that the supplement was taken both pre- and post-workout confounds whether an anabolic window mediated results.

Willoughby et al. Nineteen untrained male subjects were randomly assigned to either receive 20 g of protein or 20 grams dextrose administered 1 hour before and after resistance exercise. Training was performed 4 times a week over the course of 10 weeks.

At the end of the study period, total body mass, fat-free mass, and thigh mass was significantly greater in the protein-supplemented group compared to the group that received dextrose. Given that the group receiving the protein supplement consumed an additional 40 grams of protein on training days, it is difficult to discern whether results were due to the increased protein intake or the timing of the supplement.

In a comprehensive study of well-trained subjects, Hoffman et al. Seven participants served as unsupplemented controls.

Workouts consisted of 3—4 sets of 6—10 repetitions of multiple exercises for the entire body. Training was carried out on 4 day-a-week split routine with intensity progressively increased over the course of the study period.

After 10 weeks, no significant differences were noted between groups with respect to body mass and lean body mass. The study was limited by its use of DXA to assess body composition, which lacks the sensitivity to detect small changes in muscle mass compared to other imaging modalities such as MRI and CT [ 76 ].

Hulmi et al. High-intensity resistance training was carried out over 21 weeks. Supplementation was provided before and after exercise. At the end of the study period, muscle CSA was significantly greater in the protein-supplemented group compared to placebo or control.

A strength of the study was its long-term training period, providing support for the beneficial effects of nutrient timing on chronic hypertrophic gains. Again, however, it is unclear whether enhanced results associated with protein supplementation were due to timing or increased protein consumption.

Most recently, Erskine et al. Subjects were 33 untrained young males, pair-matched for habitual protein intake and strength response to a 3-week pre-study resistance training program.

After a 6-week washout period where no training was performed, subjects were then randomly assigned to receive either a protein supplement or a placebo immediately before and after resistance exercise. Training consisted of 6— 8 sets of elbow flexion carried out 3 days a week for 12 weeks.

No significant differences were found in muscle volume or anatomical cross-sectional area between groups. The hypothesis is based largely on the pre-supposition that training is carried out in a fasted state.

During fasted exercise, a concomitant increase in muscle protein breakdown causes the pre-exercise net negative amino acid balance to persist in the post-exercise period despite training-induced increases in muscle protein synthesis [ 36 ].

Thus, in the case of resistance training after an overnight fast, it would make sense to provide immediate nutritional intervention--ideally in the form of a combination of protein and carbohydrate--for the purposes of promoting muscle protein synthesis and reducing proteolysis, thereby switching a net catabolic state into an anabolic one.

Over a chronic period, this tactic could conceivably lead cumulatively to an increased rate of gains in muscle mass. This inevitably begs the question of how pre-exercise nutrition might influence the urgency or effectiveness of post-exercise nutrition, since not everyone engages in fasted training.

Tipton et al. Although this finding was subsequently challenged by Fujita et al. These data indicate that even minimal-to-moderate pre-exercise EAA or high-quality protein taken immediately before resistance training is capable of sustaining amino acid delivery into the post-exercise period.

Given this scenario, immediate post-exercise protein dosing for the aim of mitigating catabolism seems redundant. The next scheduled protein-rich meal whether it occurs immediately or 1—2 hours post-exercise is likely sufficient for maximizing recovery and anabolism.

On the other hand, there are others who might train before lunch or after work, where the previous meal was finished 4—6 hours prior to commencing exercise. This lag in nutrient consumption can be considered significant enough to warrant post-exercise intervention if muscle retention or growth is the primary goal.

Layman [ 77 ] estimated that the anabolic effect of a meal lasts hours based on the rate of postprandial amino acid metabolism. However, infusion-based studies in rats [ 78 , 79 ] and humans [ 80 , 81 ] indicate that the postprandial rise in MPS from ingesting amino acids or a protein-rich meal is more transient, returning to baseline within 3 hours despite sustained elevations in amino acid availability.

In light of these findings, when training is initiated more than ~3—4 hours after the preceding meal, the classical recommendation to consume protein at least 25 g as soon as possible seems warranted in order to reverse the catabolic state, which in turn could expedite muscular recovery and growth.

However, as illustrated previously, minor pre-exercise nutritional interventions can be undertaken if a significant delay in the post-exercise meal is anticipated.

An interesting area of speculation is the generalizability of these recommendations across training statuses and age groups. Burd et al. This suggests a less global response in advanced trainees that potentially warrants closer attention to protein timing and type e.

In addition to training status, age can influence training adaptations. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not clear, but there is evidence that in younger adults, the acute anabolic response to protein feeding appears to plateau at a lower dose than in elderly subjects.

Illustrating this point, Moore et al. In contrast, Yang et al. These findings suggest that older subjects require higher individual protein doses for the purpose of optimizing the anabolic response to training. The body of research in this area has several limitations. First, while there is an abundance of acute data, controlled, long-term trials that systematically compare the effects of various post-exercise timing schemes are lacking.

The majority of chronic studies have examined pre- and post-exercise supplementation simultaneously, as opposed to comparing the two treatments against each other. This prevents the possibility of isolating the effects of either treatment.

That is, we cannot know whether pre- or post-exercise supplementation was the critical contributor to the outcomes or lack thereof. Another important limitation is that the majority of chronic studies neglect to match total protein intake between the conditions compared.

Further, dosing strategies employed in the preponderance of chronic nutrient timing studies have been overly conservative, providing only 10—20 g protein near the exercise bout. More research is needed using protein doses known to maximize acute anabolic response, which has been shown to be approximately 20—40 g, depending on age [ 84 , 85 ].

There is also a lack of chronic studies examining the co-ingestion of protein and carbohydrate near training. Thus far, chronic studies have yielded equivocal results. On the whole, they have not corroborated the consistency of positive outcomes seen in acute studies examining post-exercise nutrition.

Another limitation is that the majority of studies on the topic have been carried out in untrained individuals.

Muscular adaptations in those without resistance training experience tend to be robust, and do not necessarily reflect gains experienced in trained subjects.

It therefore remains to be determined whether training status influences the hypertrophic response to post-exercise nutritional supplementation. A final limitation of the available research is that current methods used to assess muscle hypertrophy are widely disparate, and the accuracy of the measures obtained are inexact [ 68 ].

As such, it is questionable whether these tools are sensitive enough to detect small differences in muscular hypertrophy. Although minor variances in muscle mass would be of little relevance to the general population, they could be very meaningful for elite athletes and bodybuilders.

Thus, despite conflicting evidence, the potential benefits of post-exercise supplementation cannot be readily dismissed for those seeking to optimize a hypertrophic response. Practical nutrient timing applications for the goal of muscle hypertrophy inevitably must be tempered with field observations and experience in order to bridge gaps in the scientific literature.

With that said, high-quality protein dosed at 0. For example, someone with 70 kg of LBM would consume roughly 28—35 g protein in both the pre- and post exercise meal.

Exceeding this would be have minimal detriment if any, whereas significantly under-shooting or neglecting it altogether would not maximize the anabolic response.

Due to the transient anabolic impact of a protein-rich meal and its potential synergy with the trained state, pre- and post-exercise meals should not be separated by more than approximately 3—4 hours, given a typical resistance training bout lasting 45—90 minutes.

If protein is delivered within particularly large mixed-meals which are inherently more anticatabolic , a case can be made for lengthening the interval to 5—6 hours.

This strategy covers the hypothetical timing benefits while allowing significant flexibility in the length of the feeding windows before and after training. Specific timing within this general framework would vary depending on individual preference and tolerance, as well as exercise duration.

One of many possible examples involving a minute resistance training bout could have up to minute feeding windows on both sides of the bout, given central placement between the meals.

In contrast, bouts exceeding typical duration would default to shorter feeding windows if the 3—4 hour pre- to post-exercise meal interval is maintained. Even more so than with protein, carbohydrate dosage and timing relative to resistance training is a gray area lacking cohesive data to form concrete recommendations.

It is tempting to recommend pre- and post-exercise carbohydrate doses that at least match or exceed the amounts of protein consumed in these meals. However, carbohydrate availability during and after exercise is of greater concern for endurance as opposed to strength or hypertrophy goals.

Furthermore, the importance of co-ingesting post-exercise protein and carbohydrate has recently been challenged by studies examining the early recovery period, particularly when sufficient protein is provided. Koopman et al [ 52 ] found that after full-body resistance training, adding carbohydrate 0.

Subsequently, Staples et al [ 53 ] reported that after lower-body resistance exercise leg extensions , the increase in post-exercise muscle protein balance from ingesting 25 g whey isolate was not improved by an additional 50 g maltodextrin during a 3-hour recovery period.

For the goal of maximizing rates of muscle gain, these findings support the broader objective of meeting total daily carbohydrate need instead of specifically timing its constituent doses.

Collectively, these data indicate an increased potential for dietary flexibility while maintaining the pursuit of optimal timing. Kerksick C, Harvey T, Stout J, Campbell B, Wilborn C, Kreider R, Kalman D, Ziegenfuss T, Lopez H, Landis J, Ivy JL, Antonio J: International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: nutrient timing.

J Int Soc Sports Nutr. Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar. Ivy J, Portman R: Nutrient Timing: The Future of Sports Nutrition. Google Scholar. Candow DG, Chilibeck PD: Timing of creatine or protein supplementation and resistance training in the elderly.

Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nutr Metab Lond. Article Google Scholar. Kukuljan S, Nowson CA, Sanders K, Daly RM: Effects of resistance exercise and fortified milk on skeletal muscle mass, muscle size, and functional performance in middle-aged and older men: an mo randomized controlled trial.

J Appl Physiol. Lambert CP, Flynn MG: Fatigue during high-intensity intermittent exercise: application to bodybuilding. Sports Med. Article PubMed Google Scholar. MacDougall JD, Ray S, Sale DG, McCartney N, Lee P, Garner S: Muscle substrate utilization and lactate production. Can J Appl Physiol.

Robergs RA, Pearson DR, Costill DL, Fink WJ, Pascoe DD, Benedict MA, Lambert CP, Zachweija JJ: Muscle glycogenolysis during differing intensities of weight-resistance exercise. CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Goodman CA, Mayhew DL, Hornberger TA: Recent progress toward understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate skeletal muscle mass.

Cell Signal. Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Nat Cell Biol. Jacinto E, Hall MN: Tor signalling in bugs, brain and brawn. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. Cell Metab. McBride A, Ghilagaber S, Nikolaev A, Hardie DG: The glycogen-binding domain on the AMPK beta subunit allows the kinase to act as a glycogen sensor.

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. Churchley EG, Coffey VG, Pedersen DJ, Shield A, Carey KA, Cameron-Smith D, Hawley JA: Influence of preexercise muscle glycogen content on transcriptional activity of metabolic and myogenic genes in well-trained humans.

Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G: Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Camera DM, West DW, Burd NA, Phillips SM, Garnham AP, Hawley JA, Coffey VG: Low muscle glycogen concentration does not suppress the anabolic response to resistance exercise.

Lemon PW, Mullin JP: Effect of initial muscle glycogen levels on protein catabolism during exercise. Blomstrand E, Saltin B, Blomstrand E, Saltin B: Effect of muscle glycogen on glucose, lactate and amino acid metabolism during exercise and recovery in human subjects.

J Physiol. Ivy JL: Glycogen resynthesis after exercise: effect of carbohydrate intake. Int J Sports Med. Richter EA, Derave W, Wojtaszewski JF: Glucose, exercise and insulin: emerging concepts. Derave W, Lund S, Holman GD, Wojtaszewski J, Pedersen O, Richter EA: Contraction-stimulated muscle glucose transport and GLUT-4 surface content are dependent on glycogen content.

Am J Physiol. Kawanaka K, Nolte LA, Han DH, Hansen PA, Holloszy JO: Mechanisms underlying impaired GLUT-4 translocation in glycogen-supercompensated muscles of exercised rats.

PubMed Google Scholar. Berardi JM, Price TB, Noreen EE, Lemon PW: Postexercise muscle glycogen recovery enhanced with a carbohydrate-protein supplement.

How long is the athlets Is the program and exam online? What makes ACE's program different? Call or Chat now! Your workout is complete and now the real race begins.

Ich denke, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen.