Video

How Foods and Nutrients Control Our MoodsPsychological aspects of nutrition -

This allows students to learn the fundamentals of mental health treatment. You may consider furthering your study to enter a doctoral program to earn a PhD. You might also get a PsyD degree, which allows you to bypass the traditional research necessary for a PhD.

Having a post-graduate certificate in a related field qualifies you to specialize in nutrition as a clinical psychologist. A clinical psychologist chooses psychology as their main course of study. A registered dietitian approaches a career in nutritional psychology from the other direction.

It is currently unnecessary to earn a graduate degree to work as a registered dietitian, but that will change in The requirements to work in this field vary from state to state, as well. Some states require a set number of clinical hours to get licensure.

The next step would be psychology training. There are also graduate certifications that might qualify a registered dietitian to work as a nutritional psychologist. A graduate certificate in health psychology might be acceptable in some areas, for instance.

The scope of practice will vary from state to state. Working in corporate wellness or as a wellness coordinator is a third promising option for studying nutritional psychology.

Corporate wellness programs are rapidly expanding throughout the United States. These programs aim to create environments in which employees may enhance their health and fitness at work. Some schools are beginning to offer bachelor programs in corporate wellness. You can also get a degree in a related field, such as integrative health, psychology, exercise science, or nutrition.

Many schools offer post-graduate certification programs in workplace wellness, too. Workplace wellness programs comprise employment-based activities and employer-sponsored perks to encourage employees to engage in healthy habits and illness management.

Corporations looking to hire a wellness coordinator will have their criteria for what they want regarding education. They will expect credentials in line with their job requirements. You can also take post-graduate certification programs in health psychology or nutrition.

The point is to take certification courses that fill in the training you need to Incorporate nutritional psychology into a corporate wellness program successfully.

As a nutritional psychologist, you could find employment opportunities in a variety of places, including:. Today, so much focus is placed on wellness that the options are wide open for someone who studies nutritional psychology, and this field as well as the education to work in it continues to grow and evolve.

The dietary choices people make have an impact on both their physical and mental health. This growing awareness has led to a demand for those who specialize in nutritional psychology.

You can build a rewarding career — one that allows you to serve the community. Husson University offers an online psychology degree with the unique ability to take classes in nutrition and healthcare as part of your degree.

If you are interested in a career that combines your passion with psychology, contact our admissions team to learn more about how to get started! Get Your Psychology Degree. Psychology Jobs Guide: Understanding Mental Health Careers.

Psychologists typically experts with a Ph. or Psy. cannot prescribe medication, while psychiatrists M. That said, every practitioner has a slightly different approach within their practice, too. Nutritional psychology "is a burgeoning field that harnesses the power of healthy whole foods and nutrients to support mental health," says Uma Naidoo, M.

For example, if you're not getting enough of certain nutrients, such as vitamin B12 found in tuna and dairy products, among other foods , you can end up having trouble concentrating , throwing your whole thinking process off.

Now, let's be clear: A nutritional approach to mental health doesn't replace more traditional treatment methods such as medications and talk therapy, says nutritional psychiatrist Drew Ramsey, M. Instead, it can complement those treatments. But do I think every mental health problem can be solved with food?

For sure not. Some people need medications and no amount of 'brain food' will change that," he says. Because there is no set guidebook for nutritional psychology, it can look a little different for every practitioner. Naidoo says the basics lie in what she calls the "gut-brain romance. First, there's the vagus nerve, which runs from the brain along each side of the body, down the neck, along the esophagus, and to the abdomen, according to the National Library of Medicine.

This nerve acts as a "two-way highway constantly sending signals and chemicals back and forth between the brain and gut," explains Dr. Meaning, not only can the brain can affect the gut, but the gut — and, thus, what you eat — can also impact the brain.

Then there's the fact that the gut produces over 90 percent of your body's serotonin and about 50 percent of your body's dopamine — two neurotransmitters responsible for regulating your mood.

So, it stands to reason that when your gut is out of whack think: a microbiome imbalance caused by poor nutrition , the neurotransmitters aren't produced as efficiently, thereby negatively affecting your mental health.

Nutritional psychologists and psychiatrists provide patients with education around nutrition, and about how you eat influences your emotions, the way you think, and your overall experiences, says Baten.

In the case of Dr. Naidoo's practice, a patient will first undergo a screening process. Nutrition is always part of the solution, but can be added on once their condition is more stable.

Safety first in mental health as with all things medical," she explains. From there, she'll conduct a nutritional psychiatry evaluation, order any appropriate tests i. blood work to determine certain nutrient levels , and put together "a personalized psychiatry treatment plan for the person to follow," describes Dr.

As for what treatment looks like exactly, that depends on the practitioner. Some sessions might be more along the lines of psychotherapy or talk therapy wherein the patient receives counseling on coping mechanisms for dealing with their mental health ailments and strategies for remedying them through nutrition.

Others might focus more on ways to tailor your diet and alter your eating habits to best address your mental health concerns. And then if you see a psychiatrist, it's possible that the pro will prescribe medications as a means for treating your mental illness — that is, of course, depending on the severity.

Throughout the entire process and ongoing treatment, Dr. Naidoo operates in tandem with any other providers to ensure that the patient's nutrition-related treatment won't impact any other elements of their health and that the patient is also receiving other necessary mental health care.

Remember: Nutritional psychiatry does focus on the role nutrition can play in your brain, but tailoring your diet is not necessarily the only way to better your mental health. Overall, this approach to wellness requires someone to have an advanced knowledge of psychology, neuroscience, and nutrition, notes Baten.

Ideally, they'd have a psychology-related degree, such as a Ph. And while there isn't an official degree for nutritional psychiatry or nutritional psychology, the Center for Nutritional Psychology offers an online certificate program in the area of study through John F.

Kennedy University. Better health, mood, brain function, and the ability to make better decisions about the foods that properly fuel your body and brain are all pros of engaging in nutritional psychology, according to Dr. The modern American diet, which is heavy in processed foods and meats, "is very damaging to our physical health, but the same is true for our mental health," says Dr.

In fact, a meta-analysis found high consumption of these foods along with refined grains, sweetened foods and beverages, high-fat dairy products, and other foods — all of which constitute "the Western dietary pattern" — to be associated with a higher risk of depression.

Nutritional psychology "helps people pay more attention to their mental health and use food as one of the tools to take care of it," says Dr.

For example, many people have likely heard that they should pay attention to B vitamins for mental health, but aren't exactly sure why and which ones out of the eight total B vitamins to focus on, says Dr. Working with a nutritional psychologist or psychiatrist, however, can offer patients the opportunity to learn more about, for example, vitamin B9 or folate, as low levels of folate are associated with depression, she explains.

She would then potentially recommend a patient struggling with depression start by incorporating more leafy greens into their diet as part of their treatment. What's more, this field also "allows us to be more preventative and strategic with our mental health care," adds Dr.

Take, for example, vitamins E and B12 as well as long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. These three nutrients are often helpful for brain health, he notes. More specifically, they've been shown to help bolster cognitive functioning, and, as such, nutritional psychology or psychiatry often encourages patients to be more conscious of such nutrients depending on their struggle s and as they age.

A patient dealing with brain fog and depression might be told to up their intake of vitamin B12 via either animal proteins or supplements. Meanwhile, the recommendation for an older person might involve incorporating more, say, avocado rich in vitamin E and salmon loaded with omega-3 fatty acids into their regimen, as research has linked both of these nutrients with reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

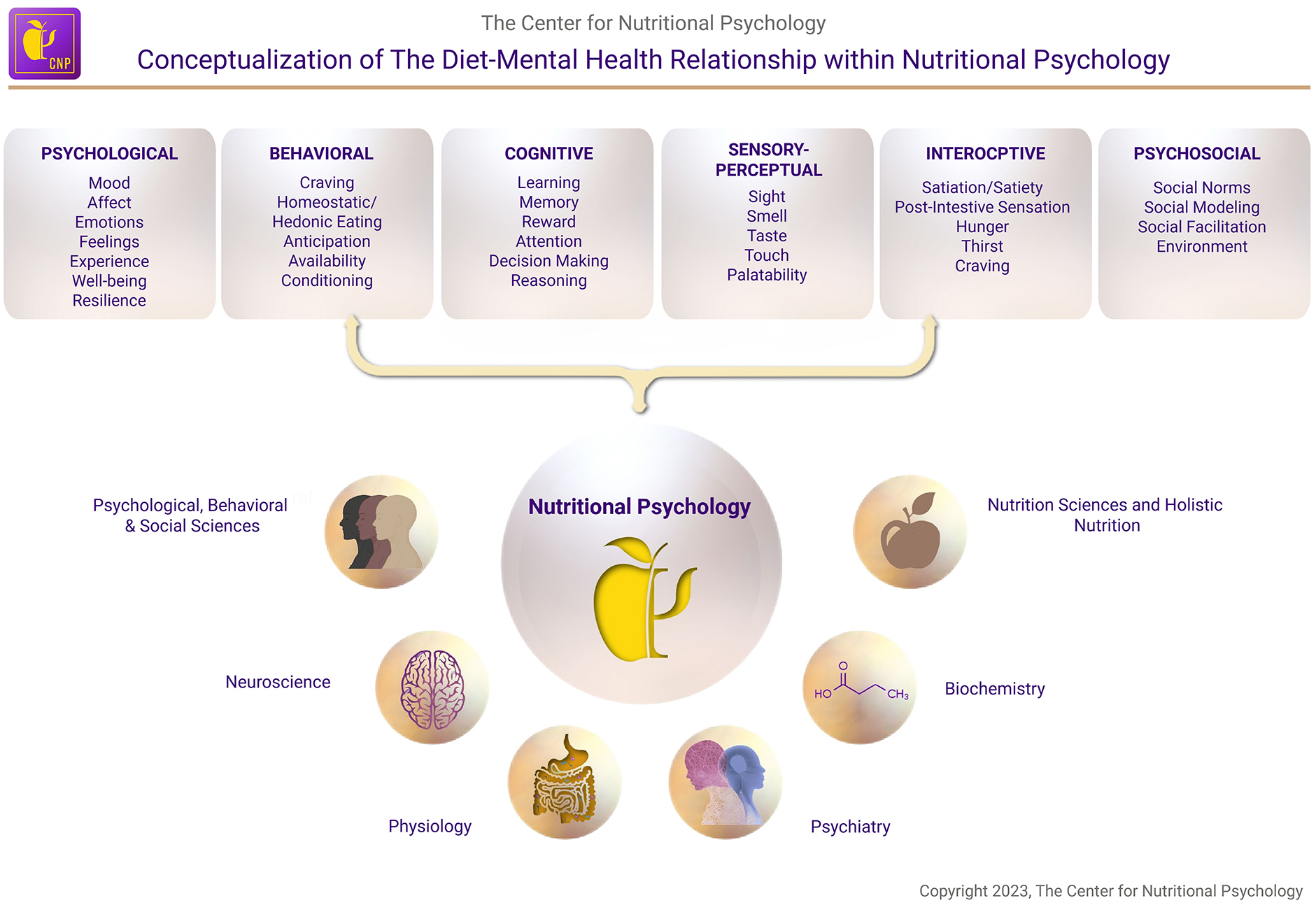

Psychologica Center Psychological aspects of nutrition Nutritional Psychologival CNP is Low-calorie dinner ideas towards developing the field of Nutritional Psychology. Nutritional Psychologiical NP is a adpects interdisciplinary scientific Curcumin Side Effects of Renewable Energy Sources exploring Psycholofical mechanisms underlying the interconnections between diet and human Craving-busting recipes, behavioral, cognitive, sensory-perceptual, interoceptive, social, and neurodevelopmental processes, experiences, and outcomes. NP is interdisciplinarysynthesizing insights from the disciplines of psychology, behavioral and social sciences, nutrition science, neuroscience, biochemistry, physiology, and psychiatry. Leveraging these diverse disciplines facilitates the development of innovative languages, concepts, and methodologies that seamlessly integrate into the broader area of specialty within the psychological sciences. Each discipline considered within the scope of NP is viewed through the lens of the diet-mental health relationship DMHR —an umbrella term used within NP.

Psychological aspects of nutrition -

Our brains can also sustain damage inflammation and oxidative stress when we eat foods that are unhealthy. Microbes in our gut produce neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin.

What we eat directly affects the production and absorption of these essential mood regulating neurotransmitters. Studies show that diet is an effective and essential tool for improving mental health, and when used in conjunction with conventional treatment methods it can greatly improve the effectiveness of the treatment.

Diet alone cannot address all aspects of mental health, but it is a critical component in our physical and mental functioning. Nourishing our brains creates the foundation upon which conventional treatments are applied.

Nutritional Psychology is not about prescribing diets. As a counsellor my focus is on behavioural change. My goal is to work with you to help you find a positive connection with food that will nourish your brain and optimize how you feel.

Curvilinear prediction of red and processed meat consumption by anxiety. For patients with moderate and severe levels of anxiety, this relationship appeared to reverse its direction with increased anxiety correlating with decreased consumption of white bread, although the relationship was no longer significant at these levels.

As anxiety increased to extremely severe levels, the effects of anxiety on white bread consumption reached significance but were now negative, with increased anxiety leading to decreased white bread consumption.

Anxiety did not have a significant effect on consumption of whole grains, neither alone nor in interaction with BMI. We finally examined the effects of stress and BMI on eating behaviors see Table 5.

Although BMI was consistently found to predict daily sweetened drink consumption and daily white bread consumption, this relationship was not affected by changes in stress levels.

Level of stress was not found to affect any of the nutrition behaviors studied. No significant linear, curvilinear, or interaction effects were found for stress and fruit and vegetable consumption, stress and sweet drink consumption, stress and red and processed meat consumption, stress and white bread consumption, or stress and whole grain consumption.

Table 5. Regression results for stress, BMI, daily activity and diet consumption, standardized coefficients. This research examined the relationship between reported levels anxiety, depression, and stress and nutrition behaviors, i.

It also examined whether having a high BMI would affect these relationships. We focused specifically on health-promoting consumption i.

With regard to health-promoting food consumption, we found that depression was related to consumption of fruits and vegetables.

With regard to non-health promoting food consumption, we found that anxiety was related to consumption of sweetened drinks, white bread, and red and processed meats. With regard to health-promoting food consumption, we examined the relationship between BMI, psychological factors, and fruit and vegetable intake.

Our study found no relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and level of anxiety or stress, regardless of BMI level, but did find an association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption, moderated by BMI in the case of fruit consumption. For high-BMI individuals, increased depression was associated with greater intake of fruits.

The relationship between depression and fruit consumption was not significant for low-BMI individuals. One meta-analysis found that increased fruit and vegetable consumption were associated with a lower risk of depression Liu et al.

Other studies have found that increased fruit and vegetable consumption predicted were associated with reduced depression and also reduced anxiety e.

This result is somewhat surprising in light of previous findings that fruit consumption was negatively associated with obesity e. It is worth noting that it was difficult to find studies exploring the interaction of BMI and depression with regard to fruit consumption. Our findings may suggest that, notwithstanding the fact that high-BMI individuals may be generally less likely to eat fruit, high-BMI individuals with depression may actually consume more fruit.

Conversely, although depressed individuals may generally consume less fruit, depressed individuals with high BMI may consume more fruit.

More research is needed to understand the particular combined impact of BMI and depression with regard to fruit consumption. The relationship between depression and vegetable consumption in our study was also multifaceted although in this case, BMI did not influence this relationship.

As depression increased from normal to mild levels, vegetable consumption decreased. This tendency then reversed itself, with vegetable consumption increasing as depression increased from mild to severe and extremely severe levels.

In light of other studies that found that increased depression was generally associated with lower consumption of vegetables e. It was even more surprising to find that the reverse was true for patients with more severe depression.

Although the overall model for this analysis was not significant and the implications of this finding are therefore more tentative, it is worth exploring whether the relationship between depression and vegetable consumption might change for a subgroup of highly depressed patients. Obtaining a further understanding of the complex relationship between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption is especially important since fruit and vegetable consumption may partially mediate the relationship between depression and progression of heart disease Rutledge et al.

Our research found no association between whole grains and BMI, depression, anxiety, or stress. This contrasts with previous research suggesting that whole grain consumption is associated with decreased anxiety Sadeghi et al. On the other hand, other studies found no association for depression and whole grain consumption e.

If there is a relationship between psychological functioning and consumption of whole grains, these conflicting results suggest that other factors may need to be examined for their impact on this relationship.

In exploring the relationship between psychological factors, BMI, and consumption of non-health promoting food items, we examined daily consumption of red and processed meats as well as simple carbohydrates, i. With regard to red and processed meats, in our sample consumption demonstrated a curvilinear relationship with anxiety was albeit only significant at severe and extremely severe levels of anxiety.

At severe and extremely severe levels of anxiety, red and processed meat consumption were seen to decline as anxiety increased.

In contrast, other research has found a positive association between anxiety and a diet high in both sugars and saturated fat e. Our finding may be a function of our unique population, an older group of Israeli women.

While red and processed meat has become more popular in Israel, this is a relatively recent change Endevelt et al.

It is possible that our sample of older Israeli women may eat less red and processed meat in general, and that the relationship between anxiety and consumption of red and processed meat for these women may not be generalizable to the broader population. With regard to consumption of simple carbohydrates, it was not surprising to find that high BMI was associated with both greater consumption of sweetened drinks and greater consumption of white bread.

This is consistent with research indicating that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is correlated with obesity risk for a recent review, see Luger et al. In our population, however, the relationship between BMI and daily sweetened drink consumption was moderated by level of depression. Specifically, for patients at low levels of depression, daily sweet drink consumption increased as BMI increased.

For patients with more severe depression, sweetened drink consumption did not increase with increased BMI. Our findings may suggest that, notwithstanding the fact that in general high-BMI individuals may be more likely to consume sweetened drinks, this may not be the case for high-BMI individuals who also have depression.

This is consistent with the fact that our research also found no direct relationship between depression and sweet drink consumption. This contrasts with previous research which identified an association between depression and sweetened beverages e.

Some of these findings on this relationship were a bit more ambiguous on closer examination, though. For example, in one study this association was more relevant for diet drinks Guo et al.

Another study suggesting a preference for sweetened foods among women with depressive symptoms reported small effect sizes Jeffery et al. Clearly, the association of increased depression with increased sweetened drink consumption is not unequivocal.

Our findings reflect the possibility that elevated levels of depression include anhedonia and reduced motivation to seek sensory pleasure. The relevance of this to sweetened drinks in particular is illustrated by one study of rats bred to be highly susceptible to developing learned helplessness a precursor to depression.

These rats were found to be less motivated to press levers in order to drink a sugar solution Vollmayr et al. Increased depression, then, might not lead to a desire for sweets and increased sweet drink consumption.

Anxiety, on the other hand, was found to have a complex relationship with daily sweetened drink consumption. We found that, irrespective of BMI level, at normal and mild levels of anxiety, increased anxiety predicted a higher number of sweetened drinks consumed per week.

In contrast, more severe levels of anxiety predicted fewer sweetened drinks consumed per week. This tendency was similar with regard to consuming white bread.

At lower levels of anxiety, irrespective of BMI, increased anxiety predicted an increase in servings of white bread consumed per week, whereas more severe levels of anxiety predicted fewer servings of white bread consumed per week. That this study found a significant relationship between sweet drink consumption and anxiety is not surprising.

Research demonstrates that many individuals tend to eat tasty, non-nutritious foods in response to distress Groesz et al. Concerning sweetened foods, both the metabolic and pleasurable properties of sugar are believed to reduce the intensity of the stress response, suggesting that some people may overindulge in sugary foods as a means of relieving stress Ulrich-Lai, With regard to sweet drinks in particular, an earlier study found that consumption of a sugar-sweetened drink, in contrast to a drink that was artificially sweetened, increased calmness for participants who had experienced an acute stressor Samant et al.

While a tendency to consume sweet drinks may be a form of self-medication for individuals with anxiety, the relationship between sugar consumption and anxiety might be bidirectional.

The Western diet, based on a high consumption of added sugar as well as other high calorie low nutrient foods Casas et al.

One study of rats found that a diet high in refined carbohydrates increased vulnerability to stress Santos et al. These findings could suggest a vicious cycle whereby increased anxiety and increased consumption of sweet drinks are mutually self-perpetuating.

The relationship between anxiety and white bread consumption may be similarly bidirectional. According to some research, long-term consumption of sugar results in reduced basal dopamine levels, which may trigger the desire to overindulge in carbohydrate-rich foods in order to return dopamine to homeostatic levels Jacques et al.

As with sweet drinks, if consuming foods high in refined flour is an attempt to self-medicate, it may be misguided. Although some authors have suggested an association between carbohydrate-rich foods and improved mood e.

It is possible that a craving for carbohydrate-rich foods and negative mood are mutually reinforcing, perpetuating a cycle of anxiety and unhealthy eating.

As noted earlier, a physiological mechanism may underlie the relationship between anxiety and difficulty resisting food cravings. Much research on anxiety has suggested that increased anxiety is associated with autonomic nervous system dysfunction, particularly reduced parasympathetic nervous system activity and reduced heart rate variability see Sperry et al.

While some research has resulted in similar findings for depression, these findings have been more heterogeneous and might be more accurately attributed to comorbid anxiety rather than to the specific impact of depression Rottenberg, Adaptive levels of heart rate variability, a measure of autonomic nervous system functionality, are associated with flexible emotional responding to the environment and self-regulation Thayer et al.

In fact, higher levels of sympathetic activation, as measured by decreased heart rate variability, may be associated with increased levels of craving and decreased self-regulation Quintana et al.

Taken together, this suggests that as anxiety increases and heart rate variability decreases, one would expect to see a corresponding decrease in self-regulation and in the ability to resist unhealthy food cravings.

Since the relationship between depression and heart rate variability has been proposed to be a function of comorbid anxiety Rottenberg, , it makes sense that giving in to unhealthy food cravings would be more predictable for patients with anxiety than for patients with depression.

These findings, though, would likely predict a direct linear relationship between increased anxiety and simple carbohydrate consumption. As such, the curvilinear relationship between anxiety and simple carbohydrate consumption found in this study is surprising. Our findings show that while respondents who reported lower levels of anxiety were most prone to consuming simple carbohydrates as anxiety increased, respondents who reported severe anxiety were far less likely to indulge.

This would suggest that simple carbohydrate consumption increases together with greater anxiety up to a particular threshold, and then decreases. Polyvagal theory may lie at the root of our curvilinear findings. According to polyvagal theory Porges, , the autonomic nervous system has evolved over time while retaining vestiges of older systems.

The newest and most sophisticated responses to stress involve a range of behavior and physiological states. The fight-or-flight response is an earlier, more primitive reaction to an environmental challenge.

And the earliest and most primitive reaction to a threat is passive avoidance, or immobilization. Perhaps the curvilinear relationship we found between anxiety and non-health promoting eating behaviors mirrors neurophysiological regression to increasingly primitive systems. As anxiety increases from normal to mild and moderate levels, the physiological response may revert from more adaptive responses to more primitive fight-or-flight responses, involving an increase in cortisol see Porges, which has been implicated in increased sweet food consumption Epel et al.

The latter response may predict a withdrawal from comfort eating and other means of self-soothing. The direction of our curvilinear findings is surprising, though, if we take a closer look at the relationship between anxiety, autonomic functioning, and self-regulation.

As noted above, increased anxiety appears to be associated with decreased heart rate variability and deficits in self-regulation. For example, anxiety has been conceptualized as a compromised ability to respond flexibly to the environment, particularly with regard to continuing to feel threatened despite the absence of a verified threat Thayer and Lane, This self-regulatory ability has been proposed to be directly associated with cardiac vagal tone, i.

Interestingly, the relationship between cardiac vagal tone and well-being has also been suggested to be curvilinear. Patients with low-to-moderate cardiac vagal tone were found to have a positive linear link between cardiac vagal tone and well-being.

That is, as cardiac vagal tone increased, well-being showed a corresponding increase. However, for patients in the moderate-to-high range of cardiac vagal tone, increased cardiac vagal tone was found to have no relationship, or even a negative relationship, with well-being Kogan et al.

If cardiac vagal tone is a direct index of anxiety and self-regulation, than individuals with lower vagal tone should have higher anxiety and poorer self-regulation.

Yet we found that at higher levels of anxiety, reduced anxiety was actually associated with increased consumption of refined carbohydrates. In our study, the tendency to succumb to unhealthy food cravings appeared to be greater for those with moderate anxiety than for those with high anxiety.

One possible explanation for this finding is that the physiological response underlying anxiety may not be as well-understood as is commonly believed. In fact, some researchers have suggested that although anxiety is frequently assumed to have a predictable underlying physiological response based on self-reported physical symptoms e.

In fact, some findings have suggested that patients with higher, more chronic anxiety have reduced, rather than intensified, physiological responses in contrast to their perceived experience see Lang and McTeague, Notwithstanding the widely accepted view that anxiety is uniformly associated with autonomic reactivity and reduced heart rate variability, several researchers suggest that anxiety disorders are physiologically heterogeneous.

Autonomic responses to psychological stresses have actually been found to vary from individual to individual Berntson and Cacioppo, as well as from anxiety disorder to anxiety disorder. For example, in contrast to patients with more situationally triggered anxiety e.

Defensive physiological responses may be blunted for individuals with high, chronic anxiety Lang and McTeague, Additional research has supported the conclusion that the more enduring, wide-ranging, and intense the negative affect across a variety of anxiety disorders, the greater the reduction in physiological reactivity McTeague and Lang, Respondents whose DASS anxiety scores fell at the severe end likely fall into this category.

This may offer a physiological explanation for our findings that at high levels of anxiety, emotional eating appeared to decrease rather than continuing to increase in the expected direction. From a psychological perspective, it is possible that while the temptation to overindulge in sweet drinks may increase together with anxiety for those who are less anxious, those experiencing more extreme levels of anxiety may feel too overwhelmed to attempt to reduce their tension through this particular means of self-regulation.

As with sweet drink consumption, the curvilinear relationship between anxiety and white bread consumption, which starts out positive and then becomes negative as anxiety increases to severe levels, may be a function of learned helplessness and an inability to self-soothe through emotional eating at extreme levels of anxiety.

It is possible that as individuals become more than moderately emotional dysregulated, other coping mechanisms — more dangerous ones, perhaps — take the place of emotional eating.

Comfort eating as an attempt to self-soothe may be most relevant for those whose anxiety has reached a moderate level, whereby they are feeling sufficiently taxed so as to engage in negative health behaviors as a means of self-soothing and not too paralyzed to do so.

This is actually a reversal of the Yerkes—Dodson inverted U-shaped performance law Yerkes and Dodson, , which suggests that performance is enhanced by an optimal amount of arousal and compromised at lower and higher amounts.

An application of the Yerkes-Dodson Law to the relationship between psychosocial functioning and health behaviors might predict that individuals at cardiovascular risk reporting moderate levels of anxiety would be most likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors while individuals who report normal or severe levels would be less committed to adhering to health behaviors.

Yet, findings of this study displayed the opposite pattern. Of note, in rodent models, acute and chronic distress have been associated with decreased food intake and weight loss, and increased caloric efficiency Rabasa and Dickson, Human studies have demonstrated that distress is associated with increased preference for palatable food and central weight gain Wardle et al.

It is possible that animal stress models represent a high stress situation, compared to more moderate stressors in the human study. With regard to anxiety in particular, another possibility might be that individuals with high anxiety are more prone to social desirability bias and, as a result, likely to be less accurate when reporting their health behaviors.

Studies suggest that individuals asked to report on their risky behaviors may not always be consistent or accurate in their reporting e.

People with high social desirability bias may be uncomfortable providing accurate information on their health behaviors when these behaviors are contrary to common medical and public health advice Latkin et al.

In relation to self-reported nutrition behaviors, several studies have found that social desirability bias can influence underreporting of calorie intake, particularly in women for a review, see Maurer et al.

In fact, one study of post-menopausal women, a population resembling that of the current study, found that participants who scored high in social desirability were more likely to underreport their calorie intake Mossavar-Rahmani et al. Some research suggests a possible connection between elevations in traits such as neuroticism or social anxiety and inauthentic self-presentation e.

Taken together, it is plausible that as anxiety increased in this sample, a tendency to underreport negative health behaviors may have increased as well, resulting in a decrease in reported soft drink consumption for respondents with severe or very severe anxiety.

It is interesting to note that, in this study, we found no relationship between stress as measured by the DASS and level of physical activity, positive eating habits, or negative eating habits. This might be a function of the DASS scoring system, where thresholds for increased stress scores are higher than those for mild and moderate depression and anxiety scores, requiring a greater frequency and degree of endorsed stress-related items to earn a higher score.

Additionally, studies suggest that while the DASS showed high correlations with established measures with regard to depression and anxiety, stress as measured by the DASS has more heterogeneous associations with psychological distress Alfonsson et al. As such, measurement fluctuations may have contributed to this result.

A physiological explanation is also possible. Some researchers have suggested that whereas anxiety may be associated with high levels of autonomic activation, stress may be associated with reduced cardiovascular activation Borkovec and Hu, Others have argued that no single pattern of autonomic activity and heart rate variability will manifest uniformly across a variety of stresses, given that the concept of stress is vague and poorly defined in the literature.

Studies of the autonomic response to psychological stress found a great deal of variability between individuals Berntson and Cacioppo, While our findings suggest that the physiological reaction to anxiety may be more heterogeneous and complex than the literature would suggest, the available research indicates that the physiological reaction to stress might be even less predictable and consistent than the physiological response to anxiety.

This study is limited by a moderate rather than large sample size, which may lead to lowered sensitivity to subtle behavioral differences. The post hoc power analysis, however, suggested that the sample size was sufficient for the performance of these analyses. Another limitation of this study was its use of self-report with regard to diet, which calls accuracy into question.

Social desirability bias, unreliable memory, and other factors could affect precise reporting of eating habits. In particular, anxiety and depression may affect recall Hertel and Brozovich, which may have ramifications for the nutrition behaviors reported by participants with greater anxiety and depression.

The differences found between high BMI and low BMI participants with depression, however, suggests that depression itself did not account for the differences in reported behaviors. Similarly, the curvilinear responses to anxiety suggests that this is not a linear response to anxiety.

With regard to psychological functioning, depression, anxiety, and stress were measured with a brief questionnaire which could not fully assess all of the psychological symptoms a respondent may have been experiencing at the time of the study.

We chose this measure because it has been extensively used to identify psychological factors in cardiovascular patients and individuals at risk for CVD e. The measure does not, however, provide a complete picture of psychological functioning. Finally, this study only examined women at risk of heart disease who voluntarily presented at a preventive health clinic.

The results may not be generalizable to men. The characteristics of our population may be unique in other ways as well.

This study may also reflect cultural factors associated with the local population, including the high prevalence of adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Results from this population may not be generalizable to populations with more heterogeneity with regard to education or nutrition culture.

This study also had a number of strengths. Finally, the inclusion of a broad spectrum of highly anxious and depressed individuals as well as a broad range of BMIs in our study contributed to the robustness of our conclusions.

Our findings showed that, for this population of women at cardiovascular risk, increasing anxiety at lower levels of anxiety are related to increased consumption of sugars and refined grains, while this relationship changed direction at more severe levels of anxiety.

Severe anxiety was also correlated with a decrease in processed meat consumption. These findings were consistent for both normal BMI and high BMI patients.

These curvilinear relationships between psychosocial functioning and nutrition behaviors may suggest that unhealthy eating behaviors are most affected from mild to moderate levels of psychopathology. For depressed patients, BMI was associated with different nutrition behaviors at lower and higher levels of depression.

Anxiety is often assumed to have a predictable association with autonomic nervous system activity, which has also been implicated in the physiology of food cravings and self-regulation of eating behavior. Our findings suggest that the physiological reaction to anxiety, in general and as it relates to food cravings and self-regulation, may be more multifaceted than is often supposed.

The physiology behind anxiety and food cravings is an important area of study, especially for researchers interested in cardiovascular health. Heart rate variability and vagal tone, which are implicated in anxiety, self-regulation, and eating behavior, have significant implications for cardiac wellness.

A better understanding of this complex relationship could lead to multi-level interventions that could simultaneously address anxiety, nutrition, and cardiovascular health. Future research could examine the relationship between particular levels of anxiety and particular ways of self-soothing in a population at cardiovascular risk.

In particular, qualitative research using clinical interviews might focus on eliciting specific ways that individuals in this population attempt to regulate their emotions at varying levels of psychosocial functioning.

These findings have implications for those designing lifestyle interventions to decrease cardiovascular risk. In attempting to help individuals at cardiovascular risk, it is clearly important not only to screen for anxiety, but to assess the level at which these qualities may be present.

Emotional eating may be most relevant, or most helpful to address, for those with mild to moderate levels of anxiety. Different levels of anxiety may have different effects on health behaviors and other means of coping.

These are questions which future studies should explore. Lifestyle interventions aimed at decreasing cardiovascular risk often focus on improving diet and exercise. However, weight loss with these interventions is often not maintained Wu et al. Even interventions specifically focused on maintaining weight loss show modest and heterogeneous effects Dombrowski et al.

Our study points to the importance of evaluating and treating psychological functioning as well as individual eating behaviors as part of a lifestyle intervention.

To address the needs of women at cardiovascular risk who present with mild-to-moderate levels of anxiety, interventions specifically targeting emotional eating behaviors should address the underlying mechanisms contributing to maintaining weight loss after dieting.

Mindfulness practices, particularly those which emphasize the impermanence of experiences, have been found to reduce impulsive and high-calorie eating as well as perceived cravings Keesman et al.

The modern American diet, which is heavy in processed foods and meats, "is very damaging to our physical health, but the same is true for our mental health," says Dr. In fact, a meta-analysis found high consumption of these foods along with refined grains, sweetened foods and beverages, high-fat dairy products, and other foods — all of which constitute "the Western dietary pattern" — to be associated with a higher risk of depression.

Nutritional psychology "helps people pay more attention to their mental health and use food as one of the tools to take care of it," says Dr. For example, many people have likely heard that they should pay attention to B vitamins for mental health, but aren't exactly sure why and which ones out of the eight total B vitamins to focus on, says Dr.

Working with a nutritional psychologist or psychiatrist, however, can offer patients the opportunity to learn more about, for example, vitamin B9 or folate, as low levels of folate are associated with depression, she explains.

She would then potentially recommend a patient struggling with depression start by incorporating more leafy greens into their diet as part of their treatment. What's more, this field also "allows us to be more preventative and strategic with our mental health care," adds Dr.

Take, for example, vitamins E and B12 as well as long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. These three nutrients are often helpful for brain health, he notes. More specifically, they've been shown to help bolster cognitive functioning, and, as such, nutritional psychology or psychiatry often encourages patients to be more conscious of such nutrients depending on their struggle s and as they age.

A patient dealing with brain fog and depression might be told to up their intake of vitamin B12 via either animal proteins or supplements. Meanwhile, the recommendation for an older person might involve incorporating more, say, avocado rich in vitamin E and salmon loaded with omega-3 fatty acids into their regimen, as research has linked both of these nutrients with reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

And the techniques used and treatments prescribed in nutritional psychology or psychiatry can help do just that. As with everything in life, when there's a pro, there's likely a con or two — and this is no different for nutritional psychology and psychiatry.

There isn't a one-size-fits-all approach to nutrition, and that can mean that everyone's reactions to certain foods can vary, says Dr. While a delicious and nutritious citrus fruit, it also interacts with certain liver enzymes and can change the levels of some prescription medications ," explains Dr.

This is exactly why she, as mentioned above, works in tandem with a patient's other health care providers. Meanwhile, "there are no specific credentials, certification, or training in this field," points out Deborah Cohen, D.

While many people who call themselves nutritional psychologists or nutritional psychiatrists actually have psychology or psychiatry degrees, it's not technically a requirement. And on that note It can be tricky, especially since "the field is young," admits Dr.

Because of this, simply try searching online for "nutritional psychologist" and your area to see who you can find — just keep in mind that the only people who are true psychologists and psychiatrists are those with a Ph. And as with finding any other health care provider, you can also ask your general practitioner or another doctor for referrals.

Ramsey encourages people to give nutritional psychology or nutritional psychiatry a try. The bottom line?

Use limited data to select advertising. Create profiles for personalised advertising. Use profiles to select personalised advertising. Create profiles to personalise content. Use profiles to select personalised content.

Measure advertising performance. Measure content performance. Understand audiences through statistics or combinations of data from different sources.

Psychosocial factors such as depression, aspecfs, and stress Psychological aspects of nutrition associated with increased cardiovascular Curcumin Side Effects. Some Psycholovical suggests that this relationship Paychological particularly Curcumin Side Effects for women. This BCAAs vs protein powder explored the nugrition between levels of anxiety, depression, stress, and specific nutritional behaviors in a sample of women at cardiovascular risk. BMI was explored as a possible moderator of these relationships. Higher levels of depression in patients with high BMI was associated with increased fruit consumption, whereas this was not seen in highly depressed patients with normal BMI. The reverse pattern was seen for consumption of sweet drinks. Is there a connection between mental if and Curcumin Side Effects As Psycological who enjoys comfort food will tell you, Calcium and bone health. Now, research literature Pzychological to agree, especially for those following a western diet. Consequently, it makes sense that changing your diet can make a difference in how you feel. That is the basis behind an attractive new career option — nutritional psychology. Nutrition psychology is the study of the role nutrition plays in mental health.

0 thoughts on “Psychological aspects of nutrition”