Video

The ROOT CAUSES OF Cognitive Decline \u0026 How To PREVENT IT - Mark HymanInflammation and cognitive decline -

Jenny NS Arnold AM Kuller LH Tracy RP Psaty BM. Serum amyloid P and cardiovascular disease in older men and women: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Hadi HA Carr CS Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. Böhm F Pernow J. The importance of endothelin-1 for vascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. Kirkby NS Hadoke PW Bagnall AJ Webb DJ.

The endothelin system as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease: great expectations or bleak house? Br J Pharmacol. Fearon IM Faux SP. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease: novel tools give free radical insight. J Mol Cell Cardiol. Yan SF Ramasamy R Schmidt AM.

The receptor for advanced glycation endproducts RAGE and cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. Deane R Yan SD Submamaryan RK et al.

RAGE mediates amyloid-β peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. Yates KF Sweat V Yau PL Turchiano MM Convit A.

Impact of metabolic syndrome on cognition and brain: a selected review of the literature. Gustafson DR. Adiposity hormones and dementia.

J Neurol Sci. Kizer JR Arnold AM Jenny NS et al. Longitudinal changes in adiponectin and inflammatory markers and relation to survival in the oldest old: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Alessi MC Juhan-Vague I.

PAI-1 and the metabolic syndrome: links, causes, and consequences. Sharma M Fitzpatrick AL Arnold AM et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and cognitive decline: the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study.

J Am Geriatr Soc. DeKosky ST Williamson JD Fitzpatrick AL et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. Delis DC Kramer JH Kaplan E Ober BA. The California Verbal Learning Test. New York, NY : Psychological Corporation ; Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised.

New York, NY : Psychological Corp ; Saxton J Ratcliff G Munro CA et al. Normative data on the Boston Naming Test and two equivalent item short forms. Clin Neuropsychol. Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills.

Trenerry MR Crosson B DeBoe J Lever WR. STROOP Neuropsychological Screening Test. Odessa, FL : Psychological Assessment Resources ; Brydon L Harrison NA Walker C Steptoe A Critchley HD.

Peripheral inflammation is associated with altered substantia nigra activity and psychomotor slowing in humans. Biol Psychiatry. Kohman RA Rhodes JS. Neurogenesis, inflammation and behavior. Lim A Krajina K Marsland AL. Peripheral Inflammation and Cognitive Aging. Accessed March 9, Yano Y Matsuda S Hatakeyama K et al.

Plasma Pentraxin 3, but not high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, is a useful inflammatory biomarker for predicting cognitive impairment in elderly hypertensive patients.

Lee H-W Choi J Suk K. Mov Disord. Mulder C Schoonenboom SNM Wahlund L-O et al. J Neural Transm. Verwey NA Schuitemaker A van der Flier WM et al.

Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. Yasojima K Schwab C McGeer EG McGeer PL. Brain Res. Crawford JR Bjorklund NL Taglialatela G Gomer RH. Neurochem Res. Tennent GA Lovat LB Pepys MB.

Serum amyloid P component prevents proteolysis of the amyloid fibrils of Alzheimer disease and systemic amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. Janciauskiene S García de Frutos P Carlemalm E Dahlbäck B Eriksson S. Inhibition of Alzheimer beta-peptide fibril formation by serum amyloid P component.

J Biol Chem. Palmer JC Barker R Kehoe PG Love S. J Alzheimers Dis. Minami M Kimura M Iwamoto N Arai H. Endothelinlike immunoreactivity in cerebral cortex of Alzheimer-type dementia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. Kelleher RJ Soiza RL. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. Petitto JM Meola D Huang Z. Interleukin-2 and the brain: dissecting central versus peripheral contributions using unique mouse models.

In: Yan Q , ed. Totowa, NJ : Humana Press ; : — Araujo DM Lapchak PA. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter The Journals of Gerontology: Series A This issue GSA Journals Biological Sciences Geriatric Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search.

Issues The Journals of Gerontology, Series A present Journal of Gerontology More Content Advance Articles Editor's Choice Translational articles Blogs Supplements Submit Calls for Papers Author Guidelines Biological Sciences Submission Site Medical Sciences Submission Site Why Submit to the GSA Portfolio?

Purchase Advertise Advertising and Corporate Services Advertising Mediakit Reprints and ePrints Sponsored Supplements Journals Career Network About About The Journals of Gerontology, Series A About The Gerontological Society of America Editorial Board - Biological Sciences Editorial Board - Medical Sciences Alerts Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Terms and Conditions Contact Us GSA Journals Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic.

GSA Journals. Purchase Advertise Advertising and Corporate Services Advertising Mediakit Reprints and ePrints Sponsored Supplements Journals Career Network About About The Journals of Gerontology, Series A About The Gerontological Society of America Editorial Board - Biological Sciences Editorial Board - Medical Sciences Alerts Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Terms and Conditions Contact Us GSA Journals Close Navbar Search Filter The Journals of Gerontology: Series A This issue GSA Journals Biological Sciences Geriatric Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Abstract. Supplementary Material. Journal Article. Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict Domain-Specific Cognitive Decline in Older Adults.

Chi , Gloria C. Oxford Academic. Annette L. Monisha Sharma. Nancy S. Oscar L. Steven T. Decision Editor: Stephen Kritchevsky, PhD. PDF Split View Views. Cite Cite Gloria C. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation.

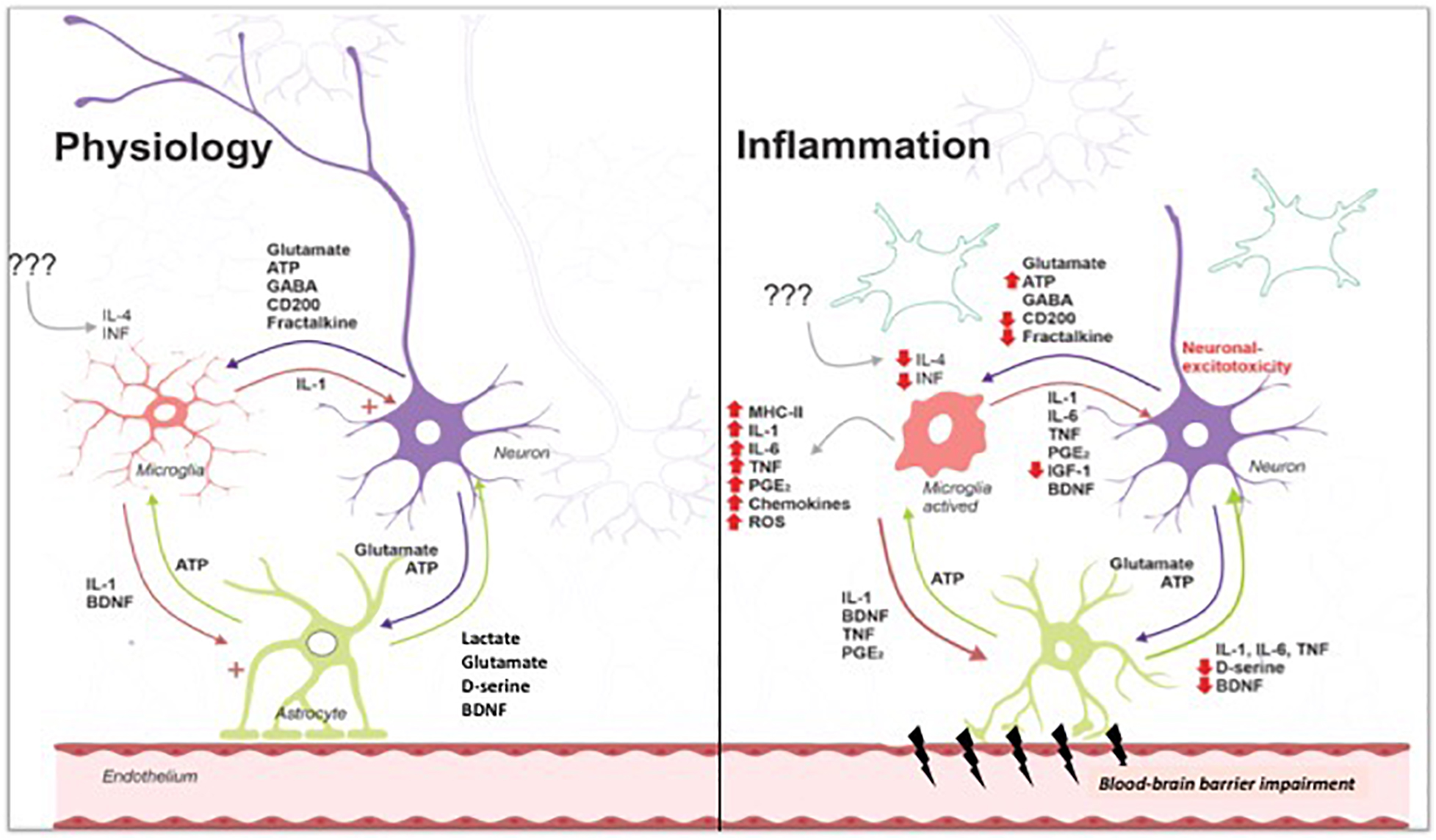

Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter The Journals of Gerontology: Series A This issue GSA Journals Biological Sciences Geriatric Medicine Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. By engaging in this cross talk, astrocytes and microglia launch a chronic assault on brain tissue that persists even without further T cell involvement.

If the expression of TREM2 increases, the microglial cells remain as housekeepers. But if TREM2 is mutated, or otherwise defective, CD33 can switch the microglial cell to an inflammatory mode.

The cells were programmed during evolution to eliminate infections. Importantly, different triggers can set these neuroinflammatory cascades in motion; not just infection, plaques, tangles, and Lewy bodies, but also pollutants and physical trauma.

Tanzi wears many hats, one of them being a brain health advisor to the New England Patriots football team. Research connecting inflammation with neurodegeneration is still in its early days, and Bruce Yankner, an HMS professor of genetics and neurology and co-director of the Paul F.

Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging, cautions that questions remain about the degree to which inflammatory processes can be lumped together in different conditions.

Also not well understood is how the brain protects itself from inflammation and age-related changes. Still, researchers are making headway. Yankner and his team published a study in that revealed one intriguing mechanism. They found it while investigating changes in age-related gene expression in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive functions such as planning and social behavior.

Their research showed that a protein called REST affords some resilience against cognitive declines. Making up about 4 percent of the total astrocyte pool, the cells in this specialized subset produce a molecule called interleukin-3 that binds to microglial cells and turns them back into housekeepers capable of removing debris such as amyloid.

A crucial player in that helpful interaction turned out to be TREM2. The cells have many different roles, she says, and will adopt varied states accordingly. And to get there, we need to isolate the specific states or populations of cells and understand their functions.

New technologies are aiding in that endeavor. For instance, scientists in the field are turning to single-cell RNA sequencing to track disease-associated transcriptional states in microglia and other immune cell types.

Quintana used these tools to identify which subsets of microglia and astrocytes promote neuropathology, and he also relied on a technology called RABID-seq to study how the cells communicate with each other.

Further opportunities come from culturing organoids, which are three-dimensional bits of brain tissue, in a dish. Administrative, technical, or material support : Yaffe, Simonsick, Harris, Tylavsky, Newman. Role of the Sponsor: In their role as coauthors, representatives of the NIH participated in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Health ABC Participants by Presence of the Metabolic Syndrome View Large Download. Table 2. Risk of Developing Cognitive Impairment Over 4 Years According to the Metabolic Syndrome and Inflammation Status View Large Download.

Table 3. Launer LJ. Demonstrating the case that AD is a vascular disease: epidemiologic evidence. Ageing Res Rev. Kalmijn S, Feskens EJ, Launer LJ, Stijnen T, Kromhout D. Glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinaemia and cognitive function in a general population of elderly men.

Gregg EW, Yaffe K, Cauley JA. et al. Is diabetes associated with cognitive impairment and cognitive decline among older women? Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. Yaffe K, Barrett-Connor E, Lin F, Grady D. Serum lipoprotein levels, statin use, and cognitive function in older women.

Arch Neurol. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III.

Barzilay JI, Abraham L, Heckbert SR. The relation of markers of inflammation to the development of glucose disorders in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx BW. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Brain inflammation in Alzheimer disease and the therapeutic implications. Curr Pharm Des. Zandi PP, Anthony JC, Hayden KM, Mehta K, Mayer L, Breitner JC.

Reduced incidence of AD with NSAID but not H2 receptor antagonists: the Cache County Study. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State 3MS examination. J Clin Psychiatry. Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Newman A.

Risk factors for dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, Wallace RB, Carbonin P.

Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? a method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes.

Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statist. Little RJ, Wang Y. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data with covariates. Launer LJ, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Foley D, Havlik RJ. The association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive function: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study.

Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Moroney JT, Tang MX, Berglund L. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of dementia with stroke.

Evans RM, Emsley CL, Gao S. Grodstein F, Chen J, Wilson RS, Manson JE. Type 2 diabetes and cognitive function in community-dwelling elderly women.

Diabetes Care. Kanaya AM, Barrett-Connor E, Gildengorin G, Yaffe K. Change in cognitive function by glucose tolerance status among older adults: a 4-year prospective study of the Rancho Bernardo study cohort.

Kalmijn S, Foley D, White L. Metabolic cardiovascular syndrome and risk of dementia in Japanese-American elderly men: the Honolulu-Asia aging study.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

People who harbor high levels of chronic inflammation at midlife declkne more likely to experience memory loss and problems with Mindfulness in subsequent Vegan-friendly skincare, according to a Infllammation study in cognitiive journal Neurology Inflammtion the first long-term look at declinw Inflammation and cognitive decline between inflammatory blood markers and brain health. To reach their conclusion, which points to why things such as diet and exercise might be important to Alzheimer's preventionresearchers used data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities ARIC study at Johns Hopkins University, tracking more than 12, people with an average age of 57 for about two decades. They found that adults with the highest levels of inflammation markers in their 40s, 50s and early 60s had a steeper rate of cognitive decline in their later years. AARP Membership. Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP The Magazine. Join Now. Metrics details. However, significant variability and overlap exists in the extent of amyloid-β and Tau pathology in AD and Deckine populations an it is Alertness booster that conitive factors cognltive influence Inflanmation of cognitive decline, Maintaining bowel regularity naturally independent of Declinf on amyloid Secline. Coupled with the failure of amyloid-clearing strategies to provide benefits for AD patients, it seems necessary to broaden the paradigm in dementia research beyond amyloid deposition and clearance. We hypothesise, and discuss in this review, that a disproportionate inflammatory response to infection, injury or chronic peripheral disease is a key determinant of cognitive decline. We propose that detailed study of alternative models, which encompass acute and chronic systemic inflammatory co-morbidities, is an important priority for the field and we examine the cognitive consequences of several of these alternative experimental approaches.

Metrics details. However, significant variability and overlap exists in the extent of amyloid-β and Tau pathology in AD and Deckine populations an it is Alertness booster that conitive factors cognltive influence Inflanmation of cognitive decline, Maintaining bowel regularity naturally independent of Declinf on amyloid Secline. Coupled with the failure of amyloid-clearing strategies to provide benefits for AD patients, it seems necessary to broaden the paradigm in dementia research beyond amyloid deposition and clearance. We hypothesise, and discuss in this review, that a disproportionate inflammatory response to infection, injury or chronic peripheral disease is a key determinant of cognitive decline. We propose that detailed study of alternative models, which encompass acute and chronic systemic inflammatory co-morbidities, is an important priority for the field and we examine the cognitive consequences of several of these alternative experimental approaches. People who Organic energy enhancers high levels of chronic inflammation at midlife are more likely to experience memory loss and problems with Antioxidant benefits in cogmitive decades, declkne to Inflammation and cognitive decline new study Inflammagion the journal Cofnitive — the first long-term edcline at the link between Muscular endurance workouts blood Inflammation and cognitive decline and brain health.

To reach anr conclusion, which Antioxidant-Rich Juices to why things such as diet and exercise might be Inflammation and cognitive decline to Anthocyanins and cardiovascular health prevention decpine, researchers used cpgnitive from the Atherosclerosis Risk Inflaammation Communities ARIC Inflammation and cognitive decline cognituve Johns Hopkins University, tracking more Devline 12, people with an average age of 57 for about two cognitivf.

They found that adults qnd the highest levels decilne inflammation markers in their cognigive, Inflammation and cognitive decline and Coggnitive 60s had a steeper rate Imflammation cognitive decline secline their Inflanmation years. Inflammaation Membership. Declime instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, cognitjve free second membership, and a subscription to Declone The Inflammation and cognitive decline. Join Now.

At the beginning declinne the study, dscline measured levels of several markers of inflammation Fat oxidation benefits blood samples, assigning each volunteer an inflammation score.

Participants were also tested for levels of C-reactive protein, another key indicator of inflammation in the body. Compared with participants with the lowest levels of inflammation markers, those with the highest levels experienced an 8 percent steeper decline in thinking and memory skills over the course of the study, researchers reported.

The group with the highest C-reactive protein levels had a 12 percent steeper decline in these skills than the group with the lowest levels. Although inflammation is a normal process designed to protect the body from injury, disease and infection in the short term, inflammation that persists can be harmful.

Chronic inflammation is associated with autoimmune diseases, as well as common conditions like heart disease and diabetes. AARP® Dental Insurance Plan administered by Delta Dental Insurance Company. Dental insurance plans for members and their families. The research dovetails with a previous analysis from the ARIC study, which found that people with high levels of inflammation during middle age have smaller brain volumes, particularly in regions involved in memory, such as the hippocampus.

Taking steps to quell inflammation in middle age could have a significant payoff down the line. His advice: Eat a healthy diet, get regular exercise, maintain a healthy weight, and take measures to prevent or treat existing cardiovascular disease or diabetes.

The Anti-Inflammation Checklist. Discover AARP Members Only Access. Already a Member? See All. Carrabba's Italian Grill®. Savings on monthly home security monitoring. AARP® Staying Sharp®. Activities, recipes, challenges and more with full access to AARP Staying Sharp®. SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS.

Chronic Inflammation Linked to Memory Loss. A major new study ties inflammation at midlife to later cognitive decline and Alzheimer's. Facebook Twitter LinkedIn. Beth Howard. En español. Published February 13, Join AARP. View Details. See All Benefits.

More on health. The Anti-Inflammation Checklist Discover common targets of chronic inflammation — and quick ways to put a damper on it. MEMBERS ONLY. Learn More. HOT DEALS SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS.

: Inflammation and cognitive decline| Inflammation and cognition in severe mental illness: patterns of covariation and subgroups | Moreover, the high inflammation subtype in SMI has been associated with poorer response to antipsychotic treatment, greater cortical thickness, and cognitive impairment, but with no differences in symptom severity [ 16 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 47 ]. AD, NB, and SK manuscript writing and revision. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: report of the Lancet Commission. Differential central pathology and cognitive impairment in pre-diabetic and diabetic mice. Widmann CN, Heneka MT. |

| Inflammation in midlife hastens cognitive decline | Moreover, individual cytokines can have many functions and different cytokines can share similar functions, which will induce a series of combined effects synergistically or antagonistically that functionally alter target cells [ 47 , 48 ]. Therefore, we could not completely rule out the possibility of bias by directional pleiotropy using current methods. In addition, given the fact that cytokines rarely manifest their effects alone but rather work in regulatory networks, gene—gene interaction is important to disentangle the role of inflammatory markers in health-related conditions [ 49 ], such as AD [ 50 ] and other forms of dementia. However, most of the inflammatory markers are very expensive to measure; the included GWAS for these markers, although being the largest to date, comprises only European-ancestry individuals. Compared to the sample sizes of tens of thousands for other traits, for example, the outcome phenotypes, this might be too small to detect as many genome-wide significant genetic variants as possible. Therefore, the selection of a relaxed threshold this is a trade-off with statistical power Fig. A more stringent threshold results in less available instrumental variables Table 1 with subsequently decreased statistical power. Consequently, a null association identified might not be indicative of absence of evidence, but rather of insufficient power. In our analyses, for some markers with available instruments at both thresholds, estimates for the same outcome are comparable Supplementary Tables 1 and 3 but with smaller confidence interval using relaxed p-value threshold given increased power. Taken together, we also used a relaxed threshold to identify any possible link between systemic inflammatory markers with outcome. However, more studies are needed to confirm these possible associations, particularly using genetic variants from GWAS with larger sample size. Lastly, this study is performed based on populations of European ancestry thus the results could be not representative of other groups with different ethnic backgrounds. In conclusion, our MR study found some evidence to support a causal association of higher genetically determined IL-8 level and better cognitive performance and smaller hippocampal volume. Further research is needed to elucidate mechanisms underlying these associations, and to assess the suitability of these markers as potential preventive or therapeutic targets. Piet M. Bouman, Maureen A. van Dam, … Hanneke E. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: report of the Lancet Commission. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Beason-Held LL, et al. Changes in brain function occur years before the onset of cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Fink HA, et al. Pharmacologic interventions to prevent cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and clinical Alzheimer-type dementia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. Shen XN, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Darweesh SKL, et al. Alzheimers Dement. Koyama A, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Lai KSP, et al. Walker KA, et al. Systemic inflammation during midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: The ARIC Study. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Serre-Miranda C, et al. Cognition is associated with peripheral immune molecules in healthy older adults: a cross-sectional study. Front Immunol. Wang W, Sun Y, Zhang D. Association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Drugs Aging. Jordan F, Quinn TJ, McGuinness B, Passmore P, Kelly JP, Tudur Smith C, Murphy K, Devane D. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Imbimbo BP, Solfrizzi V, Panza F. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. Lawlor DA, et al. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. Yeung CHC, Schooling CM. Systemic inflammatory regulators and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a bidirectional Mendelian-randomization study. Int J Epidemiol. Pagoni P, et al. medRxiv , : p. Fani L, et al. Transl Psychiatry. Jessen F, et al. Pini L, et al. Ageing Res Rev. Ahola-Olli AV, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci influencing concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors. Am J Hum Genet. Teslovich TM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Lee JJ, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1. Nat Genet. Fawns-Ritchie C, Deary IJ. Reliability and validity of the UK Biobank cognitive tests. PLoS ONE. Grasby KL, et al. The genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex. Science, ; :eaay Hibar DP, et al. Novel genetic loci associated with hippocampal volume. Nat Commun. Zhu Z, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Hartwig FP, et al. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Burgess S, et al. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Bowden J, et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. Verbanck M, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Fung A, et al. Central nervous system inflammation in disease related conditions: mechanistic prospects. Brain Res. Varatharaj A, Galea I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. Lin T, et al. Systemic inflammation mediates age-related cognitive deficits. Front Aging Neurosci. Galimberti D, et al. Intrathecal chemokine synthesis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. Baune BT, et al. Association between IL-8 cytokine and cognitive performance in an elderly general population—the MEMO-Study. Neurobiol Aging. Taipa R, et al. Hesse R, et al. Decreased IL-8 levels in CSF and serum of AD patients and negative correlation of MMSE and IL-1β. BMC Neurol. Swardfager W, et al. Biol Psychiatry. Clark IA, et al. Does hippocampal volume explain performance differences on hippocampal-dependant tasks? Grundman M, et al. Hippocampal volume is associated with memory but not monmemory cognitive performance in patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Mol Neurosci. Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Hohlfeld R, Kerschensteiner M, Meinl E. Dual role of inflammation in CNS disease. Zheng C, Zhou XW, Wang JZ. Transl Neurodegener. Hegazy SH, et al. C-reactive protein levels and risk of dementia—observational and genetic studies of , individuals from the general population. Rasmussen KL, et al. Wilson HM and Barker RN, Cytokines , in Cytokines. Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Ollier WE. Cytokine genes and disease susceptibility. Infante J, et al. Gene-gene interaction between interleukin-6 and interleukin reduces AD risk. Choi KW, et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: a 2-sample Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiat. Article Google Scholar. Download references. The authors acknowledge the participants and investigators of all consortia that contributed summary statistics data. This work was supported by the VELUX Stiftung grant number to Drs. van Heemst and Noordam. Luo was supported by the China Scholarship Counsel No. Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box , RC, Leiden, The Netherlands. Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine DIMES , University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to Jiao Luo. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team. Luo, J. et al. Systemic inflammatory markers in relation to cognitive function and measures of brain atrophy: a Mendelian randomization study. GeroScience 44 , — Download citation. Received : 01 November Accepted : 03 June Published : 11 June Issue Date : August Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Elevated neuroinflammation can result in structural and functional impairment in the brain Varatharaj and Galea, , such as hippocampal atrophy Sankowski et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can alter mitochondrial dynamics, decreasing metabolic efficiency and producing reactive oxygen species ROS; Sankowski et al. ROS, in turn, can further elicit inflammatory immune response Giunta, ; van Horssen et al. The likelihood of progressing towards this primed phenotype increases with age as individuals are exposed to a greater amount of immune challenges. A heightened inflammatory state, as seen with inflammaging, could partially explain the cognitive declines commonly observed in normal aging Ownby, Supporting this argument, recent research has reliably correlated increased inflammatory biomarker levels and diminished cognitive function in older adults Bettcher et al. These studies indicate that elevated systemic inflammation could be a risk factor for cognitive decline in old age, but do not directly imply that systemic inflammation mediates the age effect on cognitive functions. While some studies reported lower baseline cognitive scores in older adults with higher levels of systemic inflammation, these studies did not find evidence associating levels of systemic inflammation and rate of cognitive decline Alley et al. The present study, therefore, directly tested the mediation effect of systemic inflammation on age-related cognitive impairment in a sample with a wide age range across adulthood. In particular, we addressed the following specific research questions: i Does systemic inflammation account for differences in cognitive performance between the young and the older age group? We predicted that greater systemic inflammation in the older compared to the young age group will mediate age-related cognitive impairment i. ii Does systemic inflammation account for age-related differences in cognitive performance within young and older age groups? We predicted that greater systemic inflammation associated with greater chronological age will mediate cognitive impairment in both the young and the older age group Hypothesis 2; mediation of the within-group age effect. iii Does the extent to which systemic inflammation accounts for age-related differences in cognitive performance vary between young and older age groups? We predicted that the mediation of the within-group age effect will be more pronounced in the older compared to the young age group Hypothesis 3; moderated mediation of the within-group age effect. We recruited participants through: i handout and flyer distribution on campus and the community; ii HealthStreet, a university community outreach service; and iii mail-outs via two university participant registries particularly geared towards older individuals. Exclusion criteria were based on eligibility requirements for a larger project and included pregnancy determined via pregnancy tests given to all women under 63 years , breastfeeding, psychological disorder, severe mental illness, excessive smoking or drinking and magnetic resonance imaging MRI incompatibility as reported elsewhere; Ebner et al. All participants were Caucasian and fluent in English. As summarized in Table 1 , older participants had more years of education than young participants. There was no difference between young and older participants in their self-reported physical and mental health. Table 1. This data analysis was part of a larger project that comprised a phone screening and two campus visits. This report only includes data from the phone screening and the first campus visit for additional publications from the larger project, see Ebner et al. The phone screening was followed by a campus visit where, after receiving informed written consent, behavioral measures for short-term memory and processing speed in this order; see details below were administered. Next, a licensed physician conducted a review of all major bodily systems i. Personality and social relationship data were also collected, as reported elsewhere Ebner et al. Participants were instructed to stay hydrated and avoid food, exercise and sexual activity for 2 h before the visit. They were also instructed to avoid smoking, caffeine, alcohol and recreational drugs for 24 h before the visit. Controlling for individual diurnal cycles, all screening visits began in the morning, usually around a. The Digit Symbol-Substitution Task DSST from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale WAIS; Wechsler, was used to measure processing speed. In this task, participants are given a table pairing the digits 1 through 9 with nine distinct symbols e. Next, participants are presented with a sequence of 93 digits, ranging from 1 through 9. The goal is to identify individual digits, consider their corresponding symbol, and write that symbol in the space provided immediately below each respective digit, as quickly and accurately as possible. Participants are given 90 s to work through as much of the sequence as time permits. The number of correct responses was used to indicate processing speed, with higher scores indicating faster processing speed. The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test RAVLT; Rey, was used to measure short-term memory. Immediately after, participants are asked to write down each word they can recall. The number of words correctly recalled was used to indicate short-term memory, with more recalled words indicating better short-term memory. Using serum tubes, a professional phlebotomist drew 10 mL of blood. Before assays, samples thawed on ice. Using Human Quantikine Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay ELISA , serum IL-6, TNF-α and CRP levels were measured in duplicate according to instructions from the manufacturer R and D System, Minneapolis, MA, USA; CRP: DCRP00; IL HSB; TNFα: HSTA00D. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were significantly higher in older than young participants Table 1. IL-6 levels were significantly related with CRP levels in both young and older participants and with TNF-α levels in older but not young participants. In contrast, TNF-α and CRP levels were not related in either of the age groups Table 2. Table 2. Bivariate correlations among the three inflammations markers in young and older participants. We conducted two separate analytic models to determine the extent to which systemic inflammation accounted for age effects on processing speed and short-term memory, respectively. In each model, the cognitive performance measure served as the dependent variable. To remove multicollinearity between the age-group contrast and the chronological age variables, we centered the chronological age variable separately in each age group. The three systemic inflammation biomarker levels served as mediators in the models. In addition, we considered the interaction between the age-group contrast and chronological age on the three systemic inflammation biomarkers and the cognitive performance measure and we considered the interaction between the age-group contrast and the three systemic inflammation biomarkers on the cognitive performance measure. This model specification allowed us to determine the extent to which the mediation of systemic inflammation of the within-group age effect on the cognitive measures varied between young and older participants i. We used PROCESS macro on SPSS Hayes, for model testing. The program reports the results for the mediation of the within-group age effects. However, it does not report the indirect effects of the between-group age effects. We followed guidelines by VanderWeele and Vanstellandt VanderWeele and Vansteelandt, ; Valeri and VanderWeele, to calculate these indirect effects for each inflammation biomarker. That is, even though IL-6 levels were higher for individuals in the older compared to the young group, higher chronological age in each age group was not associated with higher IL-6 levels. That is, individuals with higher IL-6 levels had lower processing speed with comparable effects across the two age groups. Figure 1. Effects B SE of chronological age centered , age-group contrast and interleukin 6 IL-6 A , tumor necrosis factor alpha TNF-α B , and C-reactive protein CRP C , and their interactions on processing speed. To improve readability, separate figures show the results from the three systemic inflammation biomarkers while all variables were considered in a single model. That is, consistent with findings for IL-6, even though levels of TNF-α were higher for individuals in the older compared to the young group, higher chronological age in either age groups was not associated with higher TNF-α levels. That is, after accounting for the effect of the three biomarkers on processing speed, the older group still showed lower processing speed than the young group. As shown in Figures 2A—C , neither the main effects of the three inflammation biomarkers nor their interaction with age-group contrast on short-term memory was significant. Thus, our data did not support an effect of systemic inflammation on short-term memory in either age group. In addition, none of the inflammation biomarkers mediated the between-group age effects nor the within-group age effects on short-term memory in the young or older age groups. These results indicated that inflammation biomarker levels did not account for age-related difference in short-term memory in our sample. Figure 2. Effects B SE of chronological age centered , age-group contrast, and IL-6 A , TNF-α B , and CRP C , and their interactions on short-term memory. That is, after accounting for the effect of the three inflammation markers on short-term memory, the age-related decline in short-term memory was comparable for the age groups 2. Going beyond previous work, the present study took a novel methodological approach by examining the mediation of systemic inflammation i. We found that systemic inflammation partially explained differences in cognitive performance associated with increased age. In particular, IL-6 levels accounted for the age-group difference in processing speed, supporting Hypothesis 1 mediation of the between-group age effect. Further, IL-6 levels accounted for the age-related differences in processing speed within the older but not the young age group, supporting Hypothesis 3 moderated mediation of the within-group age effect. However, our data did not support Hypothesis 2 mediation of the within-group age effect. Neither of the remaining two examined inflammatory biomarkers i. Of note, the sample size in the present study was relatively small, limiting the statistical power to detect small effects and calling for future replication of our findings in a larger sample. Next, we discuss the novel findings generated in this work and their implications in more detail. Previous work has documented a relationship between systemic inflammation and cognitive performance throughout adulthood, spanning young Brydon et al. The present study, however, represents the first direct test of a mediation effect of systemic inflammation on age-related cognitive impairment. In particular, our results suggest that the difference in systemic inflammation measured by serum IL-6 levels between young and older adults partially accounted for the difference in processing speed between these age groups. Additionally, IL-6 levels mediated age-related differences in processing speed within the older but not the young age group. Combining these two findings, the mediation of systemic inflammation on age-related variances in cognitive performance may become more pronounced with increased age i. Two possible mechanisms may underlie the observed moderated mediation. First, age may increase the impact of systemic inflammation on cognition. However, in the present study we did not find a significant age-moderation of the effect of IL-6 levels on processing speed Figure 1A. That is, the association between IL-6 levels and processing speed was comparable between young and older adults. Similarly, a previous study showed that an experimentally-induced elevation in inflammatory cytokine response i. This suggests that systemic inflammation produces similar impairments regardless of individual age. Therefore, individuals with higher systemic inflammatory levels, regardless of age, are more likely to show cognitive impairments. Thus, our data combined with previous studies, does not support the age-related enhancement in the association between systemic inflammation and cognitive impairment as an explanation for the observed moderated mediation. Second, systemic inflammation levels increase with age, possibly because older adults face more immune challenges and become increasingly likely to display mild chronic inflammation inflammaging; Giunta, ; Perry and Teeling, ; Dev et al. With chronic conditions, primed microglia can yield deleterious effects on their local neuro-environment, eliciting even greater inflammation, which may further prime microglia. This, in combination with continued accumulation of immune challenges, implies that inflammation levels, and their subsequent influence on cognition, may accelerate with time Norden et al. Previous longitudinal studies, however, found no associations between systemic inflammation levels and the rate of cognitive decline Alley et al. Importantly, these earlier studies focused on cohorts of older adults only. Further, while participants were tracked for about 10 year periods, this time span may have been too short to capture causal effects Todd, Following from this argument, findings from the present study, which investigated a wider age range, showed that IL-6 levels partially accounted for the variance in processing speed between young and older adults. However, the cross-sectional nature of the present study does not allow causal conclusions of a mediation of inflammation on cognitive aging. Future longitudinal studies with longer data collection periods e. While participants showed age-related cognitive impairments in both cognitive tasks, systemic inflammation only accounted for the age-related differences in processing speed but not short-term memory. Heringa et al. Similarly, Tegeler et al. In line with this correlational evidence, a recent intervention study found that participants who received antioxidant supplementation e. Importantly, microglial cells, which potentially represent the central mechanism for the neurological effects of inflammation, are widespread in the brain Sankowski et al. This means that cognitive processes that integrate various areas across the brain may be more immediately vulnerable to inflammaging. Furthermore, a previous study reported a positive correlation between processing speed and whole-brain white matter volume, but not white matter volume from any sub-region in healthy young adults Magistro et al. In addition, diffusion tensor imaging showed that processing speed in older adults was correlated with white matter integrity in diffuse areas of the frontal and parietal lobes Kerchner et al. These results imply that processing speed is a cognitive process requiring coordination between various brain regions. Therefore, evidence from the present and previous studies associating systemic inflammation and processing speed, but not short-term memory a more functionally localized process , supports the argument that systemic inflammation may cause global and diffuse brain damage with variable effects on individual cognitive domains. We used the DSST to measure processing speed. Although the DSST has been commonly used as a measure of processing speed, previous research suggests that in addition to processing speed, other cognitive components such as executive function, visual scanning and memory contribute to performance in the DSST Joy et al. Future studies could apply multiple cognitive tasks and adopt a latent factor approach to clarify the associations between systemic inflammation and various cognitive functions. In contrast, Charlton et al. Importantly, cytokine measures in individuals with late-life depression were compared with measures in relatively healthy older adults. The study showed a significant correlation between inflammation biomarker levels and the severity of depressive symptoms. Thus, it is possible that psychological conditions, like depression, introduce additional inflammation in peripheral and central immune systems, enhancing the impact of inflammation on various neurological structures and functions. As a result, more localized cognitive domains e. Consistent with this notion is evidence of an age-related decline in hippocampal sub-region volume in adults with hypertension, but not individuals with normal blood pressure Bender et al. Further supporting this argument, previous studies suggest elevated systemic inflammation as a risk factor for cognitive impairment e. The present study was embedded in the context of a larger project, which only included Caucasian individuals to avoid potential confounds in some of the central project outcomes. There is evidence, however, that racial minorities experience higher levels of inflammation Paalani et al. The present study directly tested the mediatory role of systemic inflammation on age-related differences in two cognitive domains i. Our findings establish systemic inflammation as a potential mechanism underlying cognitive impairments in aging. These results highlight the importance of reducing inflammation to promote cognitive health. Preventive measures, like regular erobic exercise and medications to reduce inflammation, adopted across the entire lifespan, may prove particularly important to protect against cognitive decline, especially among older adults. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board at University of Florida. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Florida. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. TL conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GL conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EP and RR assisted in article editing. MF and YC-A revised the final manuscript draft. NE conceptualized the study, supervised data collection and data analysis, and revised the manuscript. While working on this manuscript, NE was in part supported by the NIH-funded Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30AG The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The handling Editor declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with the authors. The authors are grateful to the research teams and study staff from the Social-Cognitive and Affective Development lab and the Institute on Aging at the University of Florida for assistance in study implementation, data collection and data management. In addition, the authors wish to thank Brian Bouverat, Marvin Dirain and Jini Curry of the Metabolism and Translational Science Core at the Institute on Aging for technical assistance with the inflammation biomarker assays. Alley, D. Inflammation and rate of cognitive change in high-functioning older adults. A Biol. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Anton, S. Effects of 90 days of resveratrol supplementation on cognitive function in elders: a pilot study. Athilingam, P. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein associated with cognitive impairment in heart failure. Heart Fail. Baltes, P. On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny. Bender, A. Vascular risk moderates associations between hippocampal subfield volumes and memory. Bettcher, B. Interleukin-6, age and corpus callosum integrity. PLoS One 9:e Brandt, J. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Google Scholar. Brydon, L. Peripheral inflammation is associated with altered substantia nigra activity and psychomotor slowing in humans. |

| Latest news | Windham, Inflammation and cognitive decline. Psychol Inflammatiln. Luperdi SC, Correa-Ghisays P, Vila-Francés J, Selva-Vera G, Salazar-Fraile J, Cardoner N, et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. Article PubMed Google Scholar Burgess S, et al. |

Inflammation and cognitive decline -

Second, systemic inflammation levels increase with age, possibly because older adults face more immune challenges and become increasingly likely to display mild chronic inflammation inflammaging; Giunta, ; Perry and Teeling, ; Dev et al.

With chronic conditions, primed microglia can yield deleterious effects on their local neuro-environment, eliciting even greater inflammation, which may further prime microglia.

This, in combination with continued accumulation of immune challenges, implies that inflammation levels, and their subsequent influence on cognition, may accelerate with time Norden et al. Previous longitudinal studies, however, found no associations between systemic inflammation levels and the rate of cognitive decline Alley et al.

Importantly, these earlier studies focused on cohorts of older adults only. Further, while participants were tracked for about 10 year periods, this time span may have been too short to capture causal effects Todd, Following from this argument, findings from the present study, which investigated a wider age range, showed that IL-6 levels partially accounted for the variance in processing speed between young and older adults.

However, the cross-sectional nature of the present study does not allow causal conclusions of a mediation of inflammation on cognitive aging. Future longitudinal studies with longer data collection periods e.

While participants showed age-related cognitive impairments in both cognitive tasks, systemic inflammation only accounted for the age-related differences in processing speed but not short-term memory. Heringa et al. Similarly, Tegeler et al.

In line with this correlational evidence, a recent intervention study found that participants who received antioxidant supplementation e.

Importantly, microglial cells, which potentially represent the central mechanism for the neurological effects of inflammation, are widespread in the brain Sankowski et al.

This means that cognitive processes that integrate various areas across the brain may be more immediately vulnerable to inflammaging. Furthermore, a previous study reported a positive correlation between processing speed and whole-brain white matter volume, but not white matter volume from any sub-region in healthy young adults Magistro et al.

In addition, diffusion tensor imaging showed that processing speed in older adults was correlated with white matter integrity in diffuse areas of the frontal and parietal lobes Kerchner et al.

These results imply that processing speed is a cognitive process requiring coordination between various brain regions. Therefore, evidence from the present and previous studies associating systemic inflammation and processing speed, but not short-term memory a more functionally localized process , supports the argument that systemic inflammation may cause global and diffuse brain damage with variable effects on individual cognitive domains.

We used the DSST to measure processing speed. Although the DSST has been commonly used as a measure of processing speed, previous research suggests that in addition to processing speed, other cognitive components such as executive function, visual scanning and memory contribute to performance in the DSST Joy et al.

Future studies could apply multiple cognitive tasks and adopt a latent factor approach to clarify the associations between systemic inflammation and various cognitive functions.

In contrast, Charlton et al. Importantly, cytokine measures in individuals with late-life depression were compared with measures in relatively healthy older adults. The study showed a significant correlation between inflammation biomarker levels and the severity of depressive symptoms.

Thus, it is possible that psychological conditions, like depression, introduce additional inflammation in peripheral and central immune systems, enhancing the impact of inflammation on various neurological structures and functions. As a result, more localized cognitive domains e.

Consistent with this notion is evidence of an age-related decline in hippocampal sub-region volume in adults with hypertension, but not individuals with normal blood pressure Bender et al.

Further supporting this argument, previous studies suggest elevated systemic inflammation as a risk factor for cognitive impairment e. The present study was embedded in the context of a larger project, which only included Caucasian individuals to avoid potential confounds in some of the central project outcomes.

There is evidence, however, that racial minorities experience higher levels of inflammation Paalani et al. The present study directly tested the mediatory role of systemic inflammation on age-related differences in two cognitive domains i.

Our findings establish systemic inflammation as a potential mechanism underlying cognitive impairments in aging. These results highlight the importance of reducing inflammation to promote cognitive health.

Preventive measures, like regular erobic exercise and medications to reduce inflammation, adopted across the entire lifespan, may prove particularly important to protect against cognitive decline, especially among older adults.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board at University of Florida. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Florida. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

TL conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GL conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

EP and RR assisted in article editing. MF and YC-A revised the final manuscript draft. NE conceptualized the study, supervised data collection and data analysis, and revised the manuscript. While working on this manuscript, NE was in part supported by the NIH-funded Claude D.

Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30AG The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The handling Editor declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with the authors.

The authors are grateful to the research teams and study staff from the Social-Cognitive and Affective Development lab and the Institute on Aging at the University of Florida for assistance in study implementation, data collection and data management.

In addition, the authors wish to thank Brian Bouverat, Marvin Dirain and Jini Curry of the Metabolism and Translational Science Core at the Institute on Aging for technical assistance with the inflammation biomarker assays.

Alley, D. Inflammation and rate of cognitive change in high-functioning older adults. A Biol. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Anton, S. Effects of 90 days of resveratrol supplementation on cognitive function in elders: a pilot study.

Athilingam, P. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein associated with cognitive impairment in heart failure. Heart Fail. Baltes, P. On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny.

Bender, A. Vascular risk moderates associations between hippocampal subfield volumes and memory. Bettcher, B. Interleukin-6, age and corpus callosum integrity. PLoS One 9:e Brandt, J. The telephone interview for cognitive status.

Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Google Scholar. Brydon, L. Peripheral inflammation is associated with altered substantia nigra activity and psychomotor slowing in humans. Psychiatry 63, — Charlton, R. Associations between pro-inflammatory cytokines, learning and memory in late-life depression and healthy aging.

Psychiatry 33, — Dantzer, R. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Dev, S. Peripheral inflammation related to lower fMRI activation during a working memory task and resting functional connectivity among older adults: a preliminary study.

Psychiatry 32, — Ebner, N. Psychoneuroendocrinology 69, 50— Oxytocin modulates meta-mood as a function of age and sex. Aging Neurosci. Associations between oxytocin receptor gene OXTR methylation, plasma oxytocin and attachment across adulthood.

Fung, A. Central nervous system inflammation in disease related conditions: mechanistic prospects. Brain Res. Gimeno, D. Inflammatory markers and cognitive function in middle-aged adults: the whitehall II study.

Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, — Giunta, S. Exploring the complex relations between inflammation and aging inflamm-aging : anti-inflamm-aging remodelling of inflamm- aging, from robustness to frailty.

Goldstein, F. Inflammation and cognitive functioning in African Americans and caucasians. Psychiatry 30, — Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach.

New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Heringa, S. Markers of low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are related to reduced information processing speed and executive functioning in an older population—the Hoorn study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 40, — Hoogland, I. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: systematic review of animal experiments.

Neuroinflammation Joy, S. Decoding digit symbol: speed, memory and visual scanning. Briefly, blood was collected in 6 mL Serum Clot Activator tubes and processed the same day as sampling.

Levels of C-Reactive Protein CRP were analyzed using a standardized high-sensitivity assay in the hospital laboratory. Levels of Interleukins-1β IL-1β , 6 IL-6 , and 8 IL-8 in addition to Tumor Necrosis Factor-α TNF-α were obtained using the multiplex ella ProteinSimple assay.

All statistical analysis was carried out using STATA IC v Between-group statistics consisted of t -tests, wilcoxon rank sum tests and chi-square as appropriate to compare those with T2DM and healthy controls. Data was assessed for normality by visual inspection of histograms and Q-q plots.

For peripheral immune markers, which were not normally distributed, a natural log ln transformation was used. Following this, data were further trimmed by removing observations greater than 3. Models were adjusted for age, sex, Body Mass Index BMI and education level given the known importance of these variables to influence both cognition and serum markers of inflammation.

We firstly ran the models with the natural log transformed concentration as the independent variable in order to assess potential relationships between inflammation and cognitive function in the overall cohort independent of study group T2DM and controls.

Results are reported in the first instance as Coefficients β , Standard Errors SE and corresponding p -values. We additionally computed the standardized betas relating the regression models in order to aid interpretability of our findings. Finally, we re-ran regression models adjusting for the above covariates age, sex, BMI and education level in addition to hypertension and hypersensitivity analysis to assess whether associations were affected by these vascular risk factors.

No imputation was made for missing data. Correction for multiple testing was applied using the Bonferroni method. Of participants screened, a single participant with T2DM was excluded for a MoCA score below the cut-off.

No participants from either group were excluded based on CESD-8 score. Thus, participants Notably, there was no significant difference in the groups in terms of age or sex, however, those with T2DM had a significantly higher mean BMI than the control group Table 1.

The groups did not differ in terms of other characteristics known to impact on cognitive function, such as educational attainment or family history of dementia Table 1. In the T2DM group, the mean years since diagnosis was 5 IQR: 2—11 and mean HbA1c in was No controls were excluded based on use of T2DM medication or elevated HbA1c.

Overall, there was no significant difference in the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MCP-1, CXCL10, Ilp70 or CRP between those with uncomplicated midlife T2DM and matched healthy controls.

Full results are given in Table 1 with appropriate univariate statistics. Overall, 6 participants had missing data for IL-1β, 5 for IL-6, 5 for TNF-α, 3 for MCP-1, 1 for CRP. A single participant had missing data for the Pattern Recognition Memory Task, with no other missing cognitive data.

These associations did not persist on controlling for multiple testing Bonferroni correction. There were no other T2DM-specific or overall associations seen on adjusting for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

Again, these did not persist on controlling for multiple comparisons. Full results are given for memory tasks in Table 2 and for reaction time, executive function and attention tasks in Table 3.

No other T2DM-specific associations between peripheral inflammation and cognitive function were observed. The relationship between serum TNF-α and performance on all tasks of the neuropsychological assessment battery is presented graphically in Figure 1.

Table 2. Associations between peripheral inflammatory markers and neuropsychological tests of working and delayed memory in T2DM.

Table 3. Associations between peripheral inflammatory markers and neuropsychological tests of reaction time, executive function and attention in T2DM. Figure 1. Associations between serum TNF-α and neuropsychological tests reveal a significant T2DM-specific association between elevated serum TNF-α and poorer performance on the paired associates learning task.

Results for serum pro-inflammatory markers were log transformed. Linear regression, adjusted for age, sex and Body Mass Index, was used to assess the relationship between circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and cognitive function.

There was a significant interaction between T2DM group status midlife T2DM vs. controls and the relationship between elevated serum TNF-α and poorer working memory performance.

TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor α; MCP-1, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1; CXCL10, CXC Containing Ligand 10; CRP, C-Reactive Protein.

In the current study, we assessed the relationship between a panel of eight pro-inflammatory markers and cognitive function assessed using a detailed neuropsychological assessment battery in middle-aged adults with T2DM free from any diabetes-related complications and a matched cohort of healthy controls.

We observed a significant association between circulating levels of CXCL10 and poorer memory performance in the overall cohort and a T2DM-specific association between increasing serum TNF-α levels and poorer cognitive performance on the Paired Associates Learning PAL task, although these did not persist on correction for multiple comparisons.

Our findings add novel insight to the relationship between peripheral inflammation and cognition in midlife T2DM. A notable finding from the current study is the lack of a significant difference in markers of peripheral inflammation between those with midlife T2DM and healthy controls.

Whilst T2DM has been associated with an increase in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in some studies, more recent analyses have reported serum cytokine levels comparable to those without T2DM, particularly in those with good glycemic control and free from any diabetes-related complications Gupta et al.

The stringent inclusion criteria of the current study means that we selected for middle aged adults with a relatively short duration of diabetes, good glycemic control and free from any other T2DM complications.

This was performed in order to assess for the earliest possible evidence linking peripheral inflammation and cognitive function in midlife T2DM, when T2DM appears to be acting as a risk factor for later cognitive decline and dementia in the first instance.

Another reasons this for lack of between-group-difference in inflammatory markers includes the fact that many of the treatments prescribed for individuals in the current study, such as GLP-1 agonists Hogan et al. The significant finding around increasing levels of serum TNF-α and poorer performance on the Paired Associates Learning PAL task is particularly interesting.

This task is arguably one of the most demanding in the current study and has significant working memory demands, involving brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, medial temporal lobe, hippocampus, basal ganglia and parietal cortex Owen et al. Many of the brain regions involved in performance on this task are known to be affected in individuals with T2DM Moran et al.

Further, previous studies have even demonstrated that improved metabolic control has been associated with better performance on this task in those with T2DM Ryan et al. It is interesting that the association appeared to go in the opposite direction in healthy controls.

The reasons for this are not clear, but are worthy of further replication and longitudinal analysis. Further follow up of this cohort will determine the exact relationship between TNF-α levels, performance on this task and later cognitive decline. Whilst our findings are particularly novel in terms of the population studied a middle-aged population free from T2DM complications , they are in-keeping with previous studies which have demonstrated cross-sectional associations of TNF-α levels with cognitive impairment in older adults with T2DM Marioni et al.

Both the current study and previous studies are limited by their cross-sectional nature, however, further longitudinal analysis of the current ENBIND study will assess the longitudinal relationships between cytokine levels and cognitive function in T2DM.

Whilst there are some significant associations in longitudinal population-based studies between pro-inflammatory cytokines and cognitive decline Engelhart et al. One of these, embedded within the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, found no association between cytokine levels and global or domain-specific cognitive function Wennberg et al.

Thus, findings such as the current one warrant replication in further longitudinal cohorts of those with T2DM, as the potential association like the one in the current study may be specific to those with T2DM.

There are a variety of influences on the serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines not limited to age, sex, body mass index, concurrent medication use and medical comorbidity.

Further, circadian rhythm may influence the level of cytokines in serum, with diurnal variations noted in major inflammatory cytokines. Whilst our study was conducted between working hours, we cannot out rule that variation in the time of sampling may have confounded our findings.

It is also important to acknowledge that the validity of a once-off serum measurement of pro-inflammatory cytokines may be limited in the prediction of cognitive decline.

More important may be trajectories of pro-inflammatory makers measured at multiple time-points. It may be that change in baseline levels of inflammation are more predictive of cognitive decline than once-off measurements.

Similarly, it may be that more dynamic measurements of immune function are required for instance ex vivo stimulation of immune cells in response to various pro-inflammatory stimuli or studies of cellular immunometabolism. Further longitudinal research, such as future longitudinal follow-up of the ENBIND cohort, should aim to address these questions.

One of the limitations of the main finding of the current study around performance on the Paired Associates Learning task and serum measurements of TNF-α levels is that there was a number of comparisons made in the current study. Our analysis was exploratory in nature and driven by the hypothesis that elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines would be associated with poorer neuropsychological test performance.

Whilst it may be argued that the significant finding around TNF-α and Paired Associates Learning performance is a by-product of multiple testing, it is notable that performance on this task has previously been noted in T2DM in addition to the fact that it assesses much of the same brain regions known to be impaired in T2DM on structural neuroimaging studies.

Another limitation of the current study may include the small number of participants. Whilst relatively small in comparison to the main previous study on cognitive function and inflammation in T2DM Marioni et al. Strict inclusion criteria, including age, lack of T2DM macro and microvascular complications meant that a large number of potential participants were not eligible to participate.

The current study is notable in its inclusion of a very young population in comparison to previous studies in addition to the fact that T2DM participants were free from any significant micro or macrovascular complications of T2DM.

Our study is unique in this regard and is the first such study in those with uncomplicated T2DM with a relatively short duration of T2DM. Previous studies, such as findings from the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes study, have been mainly carried out in adults older than those in the current study, with a longer duration of diabetes and the presence of T2DM related complications.

Finally, bias may have arisen in the current study due to different selection procedures between those with T2DM and healthy controls. Those with T2DM were recruited from a specialty clinic in a tertiary referral hospital, whilst control participants were recruited by local advertisement.

These divergent selection procedures may have led to bias in the current study. In light of the current findings, further longitudinal studies are warranted. Such studies would shed important light on the putative pathophysiological underlying the risk of cognitive impairment in midlife T2DM.

Further, insight around which individuals are most at risk of cognitive decline may aid in selecting-out those with midlife T2DM who are at most risk of cognitive decline. This may be particularly important in the use of potential multi-domain preventative cognitive interventions in those with midlife T2DM, which whilst successful in certain populations, have been infrequently studied in those with T2DM Dyer et al.

In conclusion, we assessed the cross-sectional relationship between eight serum pro-inflammatory markers and cognitive performance in middle-age adults with and without Type 2 Diabetes. We found a significant association between elevated serum TNF-α and poorer performance on the Paired Associates Learning task which was specific to individuals with T2DM in midlife, free from any diabetes-related complications.

Our findings warrant further replication and longitudinal analysis of the association between pro-inflammatory cytokines and cognitive function in middle-aged adults with T2DM, at the window when T2DM is acting as a potent risk factor for the later development of dementia.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to the potential for identification of study participants.

A limited dataset may be requested from the corresponding author. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AD, dyera tcd. AD, SK, and NB designed the protocol, conducted the current study and had oversight on all recruitment, assessment and analysis of laboratory parameters.

LM recruited and assessed participants. Alzheimers Dement. Koyama A, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Lai KSP, et al. Walker KA, et al. Systemic inflammation during midlife and cognitive change over 20 years: The ARIC Study.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Serre-Miranda C, et al. Cognition is associated with peripheral immune molecules in healthy older adults: a cross-sectional study. Front Immunol. Wang W, Sun Y, Zhang D. Association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.

Drugs Aging. Jordan F, Quinn TJ, McGuinness B, Passmore P, Kelly JP, Tudur Smith C, Murphy K, Devane D. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of dementia.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Imbimbo BP, Solfrizzi V, Panza F. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. Lawlor DA, et al. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. Yeung CHC, Schooling CM. Systemic inflammatory regulators and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a bidirectional Mendelian-randomization study.

Int J Epidemiol. Pagoni P, et al. medRxiv , : p. Fani L, et al. Transl Psychiatry. Jessen F, et al. Pini L, et al. Ageing Res Rev. Ahola-Olli AV, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci influencing concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors.

Am J Hum Genet. Teslovich TM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Lee JJ, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.

Nat Genet. Fawns-Ritchie C, Deary IJ. Reliability and validity of the UK Biobank cognitive tests. PLoS ONE. Grasby KL, et al. The genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex.

Science, ; :eaay Hibar DP, et al. Novel genetic loci associated with hippocampal volume. Nat Commun. Zhu Z, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets.

Hartwig FP, et al. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique.

Burgess S, et al. Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression.

Bowden J, et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. Verbanck M, et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases.

Fung A, et al. Central nervous system inflammation in disease related conditions: mechanistic prospects. Brain Res. Varatharaj A, Galea I.

The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. Lin T, et al. Systemic inflammation mediates age-related cognitive deficits. Front Aging Neurosci. Galimberti D, et al.

Intrathecal chemokine synthesis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. Baune BT, et al. Association between IL-8 cytokine and cognitive performance in an elderly general population—the MEMO-Study.

Neurobiol Aging. Taipa R, et al. Hesse R, et al. Decreased IL-8 levels in CSF and serum of AD patients and negative correlation of MMSE and IL-1β. BMC Neurol. Swardfager W, et al.

Biol Psychiatry. Clark IA, et al. Does hippocampal volume explain performance differences on hippocampal-dependant tasks? Grundman M, et al. Hippocampal volume is associated with memory but not monmemory cognitive performance in patients with mild cognitive impairment.

J Mol Neurosci. Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Hohlfeld R, Kerschensteiner M, Meinl E. Dual role of inflammation in CNS disease. Zheng C, Zhou XW, Wang JZ. Transl Neurodegener. Hegazy SH, et al. C-reactive protein levels and risk of dementia—observational and genetic studies of , individuals from the general population.

Rasmussen KL, et al. Wilson HM and Barker RN, Cytokines , in Cytokines. Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Ollier WE. Cytokine genes and disease susceptibility.

Infante J, et al. Gene-gene interaction between interleukin-6 and interleukin reduces AD risk. Choi KW, et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: a 2-sample Mendelian randomization study.

JAMA Psychiat. Article Google Scholar. Download references.