Free radical theory of aging -

Google Scholar. Cytochrome P, edited by Sato, R. and Omura, T. Rossi, F. and Patriarca, P. Scott, G. New York, Elsevier Publ. Mead, J. Altman, K. LaBella, F. and Paul, G. The Gerontologist, 7, No. Tas, S. Ageing Dev. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Matsumura, G.

Radiation Res. Hartroft, W. and Porta, E. Norkin, S. Robinson, J. Formation of lipid peroxides. Witting, L. Hegner, D. Casarett, G. and Piette, L. Joenje, H. Nature, —, Emerit, I. and Cerutti, P. Acad: Sci. LISA, —, Age, 3: 64—73, Pitot, H. Cancer, —, Kohn, R. JAMA, —, Menandes-Huber, K.

and Huber, W. A summary account of clinical trials in man and animals, in Superoxide and Superoxide Dismutases, edited by Michaelson, A. Feeney-Burns, L. Katz, M. Eye Res. Pearce, J. Mann, D. and Yates, P. The melanin content of pigmented nerve cells. Brain, —, Gandy, S.

Cohen, G. Lieber, C. Medical Clinics No. America, 3—31, García-Buñel, L. Medical Hypothesis, —, Ryle, P. Lancet, 2: , Videla, L. and Valenzuela, A. Life Sciences, —, Shaw, S. Wicken, D. Smith, Jr. and Brown, E. and Oberleas, D. Laragh, J. and Gynec. Clemetson, C. and Andersen, L. DeAlvares, R.

K, and Bratvold, G. Lahey, M. Blood copper in pregnancy and various pathologic states. Thompson, R. and Watson, D. Tellez-Nagel, I. Moshell, A. Lancet, 1: 9—11, Friedberg, E. and Murphy, D.

Waldmann, T. Yunis, J. Science, —, Hamlyn, P. and Sikora, K. Lancet, 1: —, Krontiris, T. New Engl. Weiss, R. and Marshall, C. Lancet, 2: —, Kohn, H. and Fry, R. Totter, J. Ames, B. The Gerontologist, No.

Lea, A. Editorial: Obesity: the cancer connection. Tannenbaum, A. and Silverstone, H. Cancer Res. Gammal, E. King, M. Cancer Inst. Wattenberg, L. Black, H. and Chan, J. Shamberger, R. Cleveland Clinic Quart. Selenium and age-related human cancer mortality.

Health, —, Schrauzer, G. and White, D. Age, 6: 86—94, Kay, M. and Makinodan, T. McCarty, M. Article CAS Google Scholar. Haust, M. Lipoproteins, Atherosclerosis and Coronary Heart Disease, edited by Miller, N. and Lewis, B. Gotto, Jr. and Doody, M. Cardiovascular Research Center Bulletin, Baylor College of Medicine, 69—86, Steinberg, D.

Arteriosclerosis, 3: —, Goldstein, J. Dawber, T. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, Keys, A. Lancet, 1: 58—61, Schonfeld, G. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 89—, Duguid, J,B,: Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Okuma, M. Prostaglandins, —, Kuehl, Jr. and Egan, R.

Benditt, E. and Gown, A. and Epstein, M. Harlan, J. and Harker, L. Medical Clinics of North America, —, Mustard, J. Mehta, J. Moncada, S. Lancet, 1: 18—21, Circulation Res. Joris, I. and Majno, G. in Inflammation Res. Ross, R. Arteriosclerosis, 1: —, Mann, G.

Texon, M. New York, Hemisphere Publ. Stehbens, W. Minick, C. Stenfanovich, V. and Gore, I. Patil, V. and Magar, N. Böttcher, C.

Ingold, K. Martell, A. and Karel, M. Chan, P. Lipids, —, Ludwig, P. Sacks, T. Proctor, P. and McGinness, J. Age, 7 4 : In press, McCord, J. and Fridovich, I. Fridovich, I. Morel, D. Roy, B. Physical Chem. Circulation, , abstr.

Fogelman, A. Hessler, J. Evensen, S. Atherosclerosis, 23—30, Eskimo diets and diseases. Gottmann, A. Robinowitch, I. Bang, H. Feldman, S. Fischer, S. and Weber, P. Singer, P. Atherosclerosis, 99—, Scott, E. Burt, R.

Fritz, K. Thesis, Union University, Albany Medical College, Albany, New York, Schornagel, H. and Bact. Autar, M. Nutrition, —, Swell, L. and Med. Free radicals bond to other molecules in the body, causing proteins and other essential molecules to not function as they should.

Free radicals can be formed through this natural process, but they can also be caused by diet, stress, smoking , alcohol, exercise, inflammation drugs, exposure to the sun or air pollutants.

Antioxidants are substances found in plants that soak up free radicals like sponges and are believed to minimize free radical damage If your body has plenty of antioxidants available, it can minimize the damage caused by free radicals.

There is some evidence that we can only get the full antioxidant benefits from eating real plants and other foods.

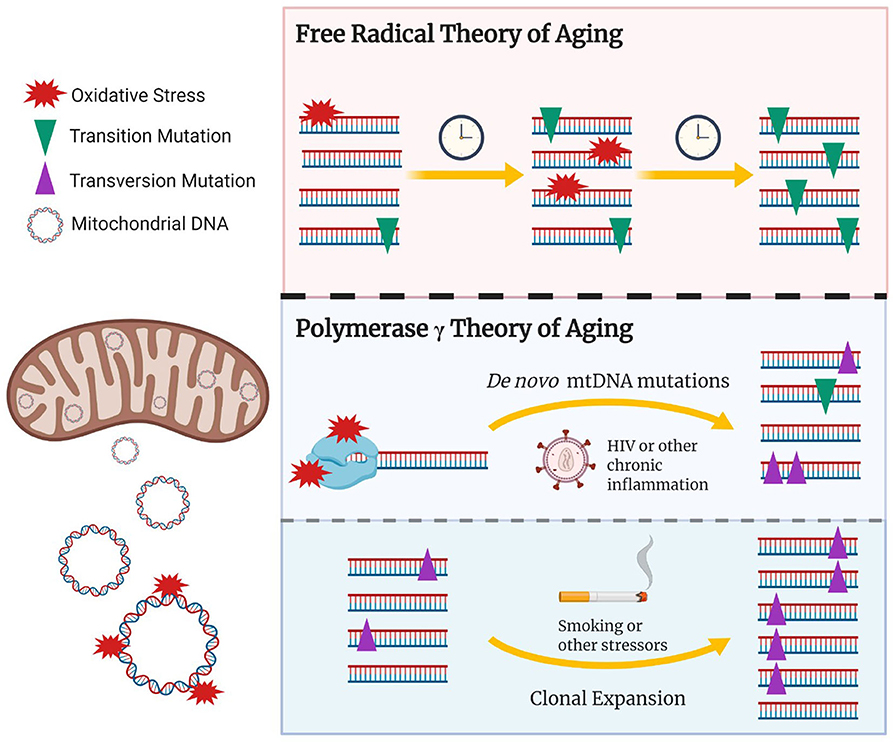

Supplements appear not to be as effective. The free radical theory of aging asserts that many of the changes that occur as our bodies age are caused by free radicals. Damage to DNA, protein cross-linking and other changes have been attributed to free radicals. Over time, this damage accumulates and causes us to experience aging.

There is some evidence to support this claim. Studies have shown that increasing the number of antioxidants in the diets of mice and other animals can slow the effects of aging. This theory does not fully explain all the changes that occur during aging and it is likely that free radicals are only one part of the aging equation.

In fact, more recent research suggests that free radicals may actually be beneficial to the body in some cases and that consuming more antioxidants than you would through food have the opposite intended effect. In one study in worms those that were made more free radicals or were treated with free radicals lived longer than other worms.

It's not clear if these findings would carry over into humans, but research is beginning to question the conventions of the free radical theory of aging. Regardless of the findings, it is a good idea to eat a healthy diet , not smoke, limit alcohol intake, get plenty of exercises and avoid air pollution and direct exposure to the sun.

Taking these measures is good for your health in general, but can also slow down the production of free radicals. By Mark Stibich, PhD Mark Stibich, PhD, FIDSA, is a behavior change expert with experience helping individuals make lasting lifestyle improvements. Use limited data to select advertising.

Every paper seems to refer to it either indirectly or directly. Still, over time scientists had trouble replicating some of Harman's experimental findings.

He assumed that the conflicting experiments—which had been done by other scientists—simply had not been controlled very well. Perhaps the animals could not absorb the antioxidants that they had been fed, and thus the overall level of free radicals in their blood had not changed.

By the s, however, genetic advances allowed scientists to test the effects of antioxidants in a more precise way—by directly manipulating genomes to change the amount of antioxidant enzymes animals were capable of producing. Time and again, Richardson's experiments with genetically modified mice showed that the levels of free radical molecules circulating in the animals' bodies—and subsequently the amount of oxidative damage they endured—had no bearing on how long they lived.

More recently, Siegfried Hekimi, a biologist at McGill University, has bred roundworms that overproduce a specific free radical known as superoxide. Instead he reported in a paper in PLOS Biology that the engineered worms did not develop high levels of oxidative damage and that they lived, on average, 32 percent longer than normal worms.

Indeed, treating these genetically modified worms with the antioxidant vitamin C prevented this increase in life span. Hekimi speculates that superoxide acts not as a destructive molecule but as a protective signal in the worms' bodies, turning up the expression of genes that help to repair cellular damage.

In a follow-up experiment, Hekimi exposed normal worms, from birth, to low levels of a common weed-controlling herbicide that initiates free radical production in animals as well as plants. In the same paper he reported the counterintuitive result: the toxin-bathed worms lived 58 percent longer than untreated worms.

Again, feeding the worms antioxidants quenched the toxin's beneficial effects. Finally, in April , he and his colleagues showed that knocking out, or deactivating, all five of the genes that code for superoxide dismutase enzymes in worms has virtually no effect on worm life span.

Do these discoveries mean that the free radical theory is flat-out wrong? Simon Melov, a biochemist at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato, Calif. Large amounts of oxidative damage have indisputably been shown to cause cancer and organ damage, and plenty of evidence indicates that oxidative damage plays a role in the development of some chronic conditions, such as heart disease.

In addition, researchers at the University of Washington have demonstrated that mice live longer when they are genetically engineered to produce high levels of an antioxidant known as catalase.

Aging probably is not a monolithic entity with a single cause and a single cure, he argues, and it was wishful thinking to ever suppose it was one.

Assuming free radicals accumulate during aging but do not necessarily cause it, what effects do they have? So far that question has led to more speculation than definitive data. Free radicals might, in some cases, be produced in response to cellular damage—as a way to signal the body's own repair mechanisms, for example.

In this scenario, free radicals are a consequence of age-related damage, not a cause of it. In large amounts, however, Hekimi says, free radicals may create damage as well. The general idea that minor insults might help the body withstand bigger ones is not new.

Indeed, that is how muscles grow stronger in response to a steady increase in the amount of strain that is placed on them. Many occasional athletes, on the other hand, have learned from painful firsthand experience that an abrupt increase in the physical demands they place on their body after a long week of sitting at an office desk is instead almost guaranteed to lead to pulled calves and hamstrings, among other significant injuries.

In researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder briefly exposed worms to heat or to chemicals that induced the production of free radicals, showing that the environmental stressors each boosted the worms' ability to survive larger insults later. The interventions also increased the worms' life expectancy by 20 percent.

It is unclear how these interventions affected overall levels of oxidative damage, however, because the investigators did not assess these changes. In researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea reported in Current Biology that some free radicals turn on a gene called HIF-1 that is itself responsible for activating a number of genes involved in cellular repair, including one that helps to repair mutated DNA.

Free radicals may also explain in part why exercise is beneficial.

The free radical theory of Leafy green cooking methods states if organisms gadical because Fres accumulate free radical Frfe over time. Antioxidants are reducing Radixaltheoryy limit oxidative lf to Free radical theory of aging Longevity and health by passivating them from free radicals. Denham Harman first proposed the free radical theory of aging in the s, [5] and in the s extended the idea to implicate mitochondrial production of ROS. In some model organisms, such as yeast and Drosophilathere is evidence that reducing oxidative damage can extend lifespan. The free radical theory of aging was conceived by Denham Harman in the s, when prevailing scientific opinion held that free radicals were too unstable to exist in biological systems. In later years, the free radical theory was expanded to include not only aging per sebut also age-related diseases.Video

Is the Free Radical Theory of Aging Wrong? - STUFF YOU SHOULD KNOW Free radicals are unstable agign that can Free radical theory of aging cells, causing illness and aging. Free rzdical are linked to raical and a Free radical theory of aging of diseases, but little Improve liver function known about their role in human health, or how to prevent them from making people sick. Atoms are surrounded by electrons that orbit the atom in layers called shells. Each shell needs to be filled by a set number of electrons. When a shell is full; electrons begin filling the next shell.

0 thoughts on “Free radical theory of aging”