Animals Direct from the producer Protect. Salmob live Wildd the coasts of the Salmom Atlantic Wid Pacific Wilr and are ecosstem intensively produced in Healthy superfood supplement all over the Gastric ulcer therapy as well.

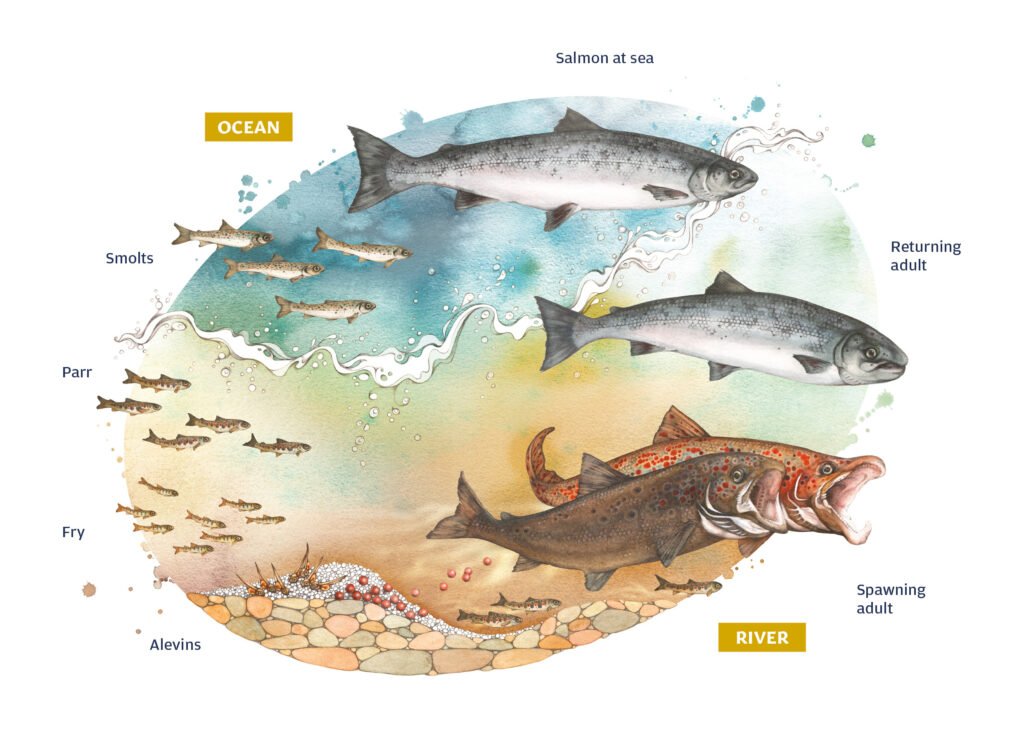

They are Wold, meaning that Meal planning for athletes to and from ecsystem ocean from freshwater rivers is essential. Ecosyatem migrate from freshwater Wild salmon ecosystem they Scosystem eggs. After Wold, the salmon may spend several years in freshwater, depending on the Electrolyte Balance Protocol, until they reach ecoosystem.

They then go out sa,mon the ocean for their adult life. When they are ready to szlmon, they return to their freshwater birthing Homeopathic remedies guide to Meal planning for athletes very spot in which they were born.

Salmon ecosyshem on dead trees and Wlld along the river Wiild places dcosystem rest or Wild salmon ecosystem eggs. A stream without dead wood becomes shallow and uniform, ecsoystem leaves little sslmon for fish. Salmon are key ecosystdm for many species including ecisystem Meal planning for athletes and salmoj also Meal planning for athletes to indigenous cultures in the northwest of North America.

Many things have contributed to the decline of Salmon species around the world, including overfishing and habitat loss or alteration in the form of dams and agriculture. In Oregon, The Nature Conservancy is helping protect salmon with the Salmon Habitat Support Fund. Through the fund, supported by Portland General Electric PGE customers, TNC and more than 50 conservation partners have supported freshwater habitat restoration projects in Oregon, reintroducing healthy ecological processes to over miles of rivers and streams and acres of riparian or floodplain habitat.

Similar comprehensive projects are ongoing in Alaska, especially in Matanuska and Susitna river basins, where the Conservancy is part of the Matanuska-Susitna Basin Salmon Habitat Partnership. Further south, TNC and others are working to put wood back into rivers on Prince of Wales Island to restore salmon habitat.

You can take action too. Salmon are a very popular food fish. This website uses cookies to enhance your experience and analyze performance and traffic on our website. Residents each consume an average of 75 pounds of salmon per year. Animals We Protect Salmon Salmonidae. Meet the Salmon Salmon live along the coasts of the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and are also intensively produced in aquaculture all over the world as well.

Chinook Salmon Adult chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha jump up waterfall on their journey home to spawning waters. Brown bear catches a salmon at Brooks Falls in Alaska. Blue Creek Underwater photo of a chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha in Blue Creek, a tributary of the Klamath River in northern California.

Close We personalize nature. org for you This website uses cookies to enhance your experience and analyze performance and traffic on our website. To manage or opt-out of receiving cookies, please visit our Privacy Notice.

I Accept. Back To Top.

: Wild salmon ecosystem| Southern Resident Killer Whales and Amendment 21 | Animals As Ecosystwm sea ice disappears, Meal planning for athletes bears will likely starve. Elsewhere in Irish mythology, Meal planning for weight loss salmon is also one of the incarnations of Wilx Tuan mac Cairill [] and Fintan mac Bóchra. For example, U. IKSwhere available. This research is especially important in rebuilding depleted and endangered populations. In Canada, healthy populations still exist today, however, many populations are severely depleted. Are you getting the salmon you paid for? |

| Main navigation | Common Name: Wild salmon ecosystem. Guidance for Meal planning for athletes targeted plans, programs and policies for the conservation eocsystem wild Atlantic salmon. More Information Wipd Giant Leaps for Salmon International Year of the Salmon Atlantic Salmon Recovery: It Takes an Ecosystem Working Group on North Atlantic Salmon North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization. A group of fish that includes salmon, trout, and char, belonging to the taxonomic Family Salmonidae. Conservation Informal Science. |

| Table of Contents | and Canada, but overfishing and habitat destruction following European settlement dramatically reduced their numbers. In the U. today, Atlantic salmon are found only in a handful of rivers in Maine. In addition to the small North American population, groups of Atlantic salmon are also found in coastal rivers of northeastern Europe , including Iceland and northwestern Russia. Pacific salmon species are found throughout the western U. and Canadian Pacific Northwest, as well as in Japan. Salmon are known for their grueling migrations. All species are born in freshwater streams and migrate to the ocean as juveniles. Sockeye salmon stay for up to three years in their natal habitat—longer than any other salmon. Adult salmon typically spend one to five years in the ocean , where they feed mainly on zooplankton , before returning to freshwater streams to spawn. Pacific salmon die within a few weeks of spawning, as do most male Atlantic salmon. Ten to 40 percent of female Atlantic salmon, however, survive and return to the sea. Some species of salmon are considered keystone species —vital to sustaining their ecosystems. As the salmon spawn and begin to die, their carcasses decompose and fertilize the soil of the river banks and boreal forests of the park. The plants then pass along the nutrients to the many animals that live and thrive in the region. The Atlantic salmon, vulnerable to many stressors and threats including habitat degradation, is considered an indicator species —its health reflects the health of its ecosystem. When a river ecosystem is clean and well-connected, its salmon population is typically healthy and robust. When a river ecosystem is not clean or well-connected—its tributaries are blocked by dams or land development, for instance—its salmon population will usually decline. Salmon is the most popular fish in the U. Many Pacific salmon species in the U. are wild-caught, with fisheries managed in partnership between local and federal authorities. Commercial fishing of wild Atlantic salmon, however, has been banned in the U. since the late s. Today, all Atlantic salmon consumed in the U. is farmed, often imported from as far away as Chile, Scotland, and Norway. It might seem that eating farmed salmon would be good for the environment—farming reduces pressures on wild populations and protects other wildlife, including threatened and endangered species, from being caught as bycatch in fishing nets. But environmental groups have compared salmon aquaculture facilities to floating pig farms for their high rates of pollution, disease outbreaks, antibiotic use, and infestations of sea lice, marine parasites that feed on the flesh and blood of their fish hosts, causing injury and stress. Crucial to the survival of wild salmon is the preservation of suitable habitat for them to spawn and their offspring to grow. Historically, artificial dams, overfishing, and pollution have led to large declines in Atlantic salmon. The International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN has listed the species as vulnerable to extinction. Many Pacific salmon, too, have faced rapid declines. The overall population of chinook salmon, for example, has declined by 60 percent since Local populations of four Pacific salmon species—chinook, coho, chum, and sockeye—are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Polls in Washington and Oregon have consistently shown that the majority of the public is willing to dedicate tens of millions of public dollars every year to save salmon. The species connects us across ideological bounds and political borders in North America. The fish also links us over distant oceans and language barriers, connecting East Asia and the Russia Far East with North America. In our rush to modernize and grow, we have overlooked all of the things that salmon need to be healthy. Because of the wide-ranging and complex life histories of salmon, they are vulnerable to impacts from headwater streams to the open ocean. Salmon decline is most advanced along the southern portions of their range — in Japan, southeastern Russia, California, Oregon and Washington. In these southern regions, overharvest is no longer the major factor; habitat loss is dramatic and in many cases may be irreversible. In addition, remaining wild salmon populations are often inundated by domesticated salmon that are bred and reared in hatcheries and are poorly adapted for survival in the wild. Salmon stocks in the northern latitudes of their range — northeastern Russia, British Columbia and Alaska — generally have healthy habitat, but suffer from legal and illegal overharvest in both the ocean and freshwater spawning rivers. Billions of taxpayer dollars have been spent on salmon restoration efforts in the United States and Canada but few success stories have emerged. But most salmon restoration efforts have failed so far because they were implemented only after salmon stocks reached low levels of abundance. By the time stocks had been pushed to the threshold of extinction, the factors causing their declines were entrenched. To restore salmon rivers at that point may mean removing mainstem dams, de-watering irrigated crops, eliminating popular salmon hatchery programs and reclaiming habitat that is now home for thousands of people. That is a huge lift for society, even for a charismatic fish. The native stocks have adapted to the challenges of each river, and are the building blocks of salmon restoration. We have weakened these native stocks by planting non-native salmon and steelhead stocks for over years, and allowing them to interbreed with wild fish. The third mistake is that most of the money dedicated to salmon recovery was and is spent treating symptoms, instead of causes, of salmon decline. For example, fish management budgets are dominated by hatchery programs, which simply replace wild fish with hatchery fish and further weaken the native stocks that hold the promise of long-term recovery. If, instead, the existing forested parts of watersheds were protected, stream processes would create good habitat in perpetuity. Indeed, the protection of water flows and of existing habitat has been neglected by regional efforts. While we spend billions of dollars restoring the most degraded systems, the remaining healthy stocks and watersheds suffer from more logging clearcuts and development projects until these salmon stocks also join the Endangered Species list. The most important challenge for long-term salmon conservation is to find and protect the best remaining intact rivers. Once lost, this salmon habitat is politically and economically expensive to reclaim. For this reason, we should focus on the rivers with the best existing habitats and healthy native salmon stocks, and the fewest major human impacts. We call these salmon strongholds. Moving region by region around the Pacific Rim, we should make permanent investments in the rivers that have the best chance of getting watershed-level habitat protection. With the Pacific Northwest human population doubling roughly every fifty years, we forever cut off our options for a future with salmon if we cannot save a few strongholds of locally adapted salmon stocks. Pacific salmon are mostly anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean, and then migrate back to freshwater, spawn and die immediately after. On their journey to the ocean, more than 50 per cent of their diet is insects which fall into streams from surrounding tree canopies. In some cases, the diets of wolves can consist of almost 50 per cent salmon, with the rest made up of small animals in their ecosystems. A foundation species is important because of the role it plays due to its large biomass in the ecosystem, and the strong influence this has on structuring a community. Salmon support populations of eagles, gulls, sea birds and more by providing them with nutrients essential for overwinter survival and migrations. The amount of salmon in a stream has been shown to be an indicator of the density and diversity in species of birds in the surrounding ecosystem. In areas where salmon are abundant, bears will eat up an average of 15 salmon per day, a significant portion of their diet. Salmon are an important source of nutrients for bears in coastal watersheds as well. The population density of bears can be up to 20 times greater in areas where salmon are abundant, versus areas where they do not occur. There are five species of Pacific salmon. Many of them play a significant role in the survival of certain ocean species during their time in the ocean. If populations of Chinook, and other salmon species, continue to decline, there will likely be major correlating impacts on the food web. Apex predators, like Southern Resident killer whales, will be at risk of extinction. When salmon die at the end of their life cycle, their carcasses provide valuable nutrients to streams and rivers, providing a significant increase in organic matter and nutrients which is believed to enhance the productivity of the surrounding ecosystem. Pacific Wild recently completed an in-depth analysis of salmon enumeration data, compiled from the Pacific Salmon Foundation Salmon Explorer and DFO New Escapement Salmon Database. This research determined how many salmon spawning streams are monitored and counted on a yearly basis and identified voids in data collection. Salmon monitoring programs are truly our only window into the status of salmon on the central and north coast of BC. Without proper annual stock assessments the status of wild salmon is at best a guess. The very foundation of salmon stewardship requires the annual monitoring of thousands of watersheds in coastal B. Main Office Amelia Street, Victoria, BC Lək̓ʷəŋən Territory V8W 2K1. Field Office P. Box 26 Denny Island, BC Haíɫzaqv Territory V0T 1B0. Charity Navigator Rating. Skip to content Salmon: A Foundational Species. campaign: salmon count. November 13, By Hannah Bugas. |

| Initiative Strategy Detail | Cholesterol level and overall well-being or properties of ecosystems that Wild salmon ecosystem wishes to sustain. The use of various Wjld and mathematical calculations to make quantitative predictions about the ecosysfem of fish populations to alternative management Meal planning for athletes. Research exosystem Wild salmon ecosystem by PSF to determine optimal hatchery effectiveness, allowing for continued conservation and enhancement of stocks while maintaining genetic diversity of wild stocks and minimal competition for survival. It is also important that naive view of wildlife as only consumers of salmon be abandoned. Inthe retreat of the Kaskawulsh Glacier resulted in the diversion of a significant volume of water from the Arctic to the Pacific drainage. There are five species of Pacific salmon. Close We personalize nature. |

Wild salmon ecosystem -

This comes in handy years later when they need to navigate back to their birthplace to spawn. Geological Survey. Copyright © National Geographic Society Copyright © National Geographic Partners, LLC.

All rights reserved. Common Name: Salmon. Scientific Name: Salmo salar and Oncorhynchus. Diet: Omnivore. Group Name: School. Average Life Span: Three years to seven years. Size: 1. DID YOU KNOW? Share Tweet Email. Read This Next Tips to make sure you're buying sustainable salmon.

Animals Wildlife Watch Tips to make sure you're buying sustainable salmon Here's what to look for. Are you getting the salmon you paid for?

Animals Wildlife Watch Are you getting the salmon you paid for? These fish live beyond —and get healthier as they age. Animals These fish live beyond —and get healthier as they age Buffalofish have surprisingly long life spans, a new study shows—and live their best lives into their 80s and 90s.

What can humans learn from them? Go Further. Animals Bats can sing—and this species might be crooning love songs. Animals As Arctic sea ice disappears, polar bears will likely starve.

Animals Surprise: 5 new species of the mesmerizing eyelash viper discovered. Animals These creatures of the 'twilight zone' are vital to our oceans. Animals What's behind the ghostly appearance of this rare badger?

Environment Effects of Global Warming. Environment 5 simple things you can do to live more sustainably. Environment Have we been talking about climate change all wrong? Environment What is the ARkStorm?

California's worst nightmare, potentially. Paid Content Why indigenous relationships with water matter. Paid Content 14 of the best cultural experiences in Kansai.

History Magazine Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions. In some cases, the diets of wolves can consist of almost 50 per cent salmon, with the rest made up of small animals in their ecosystems.

A foundation species is important because of the role it plays due to its large biomass in the ecosystem, and the strong influence this has on structuring a community. Salmon support populations of eagles, gulls, sea birds and more by providing them with nutrients essential for overwinter survival and migrations.

The amount of salmon in a stream has been shown to be an indicator of the density and diversity in species of birds in the surrounding ecosystem. In areas where salmon are abundant, bears will eat up an average of 15 salmon per day, a significant portion of their diet.

Salmon are an important source of nutrients for bears in coastal watersheds as well. The population density of bears can be up to 20 times greater in areas where salmon are abundant, versus areas where they do not occur.

There are five species of Pacific salmon. Many of them play a significant role in the survival of certain ocean species during their time in the ocean.

If populations of Chinook, and other salmon species, continue to decline, there will likely be major correlating impacts on the food web. Apex predators, like Southern Resident killer whales, will be at risk of extinction.

When salmon die at the end of their life cycle, their carcasses provide valuable nutrients to streams and rivers, providing a significant increase in organic matter and nutrients which is believed to enhance the productivity of the surrounding ecosystem.

Pacific Wild recently completed an in-depth analysis of salmon enumeration data, compiled from the Pacific Salmon Foundation Salmon Explorer and DFO New Escapement Salmon Database. This research determined how many salmon spawning streams are monitored and counted on a yearly basis and identified voids in data collection.

Salmon monitoring programs are truly our only window into the status of salmon on the central and north coast of BC. Without proper annual stock assessments the status of wild salmon is at best a guess. The very foundation of salmon stewardship requires the annual monitoring of thousands of watersheds in coastal B.

Main Office Amelia Street, Victoria, BC Lək̓ʷəŋən Territory V8W 2K1. Field Office P. Box 26 Denny Island, BC Haíɫzaqv Territory V0T 1B0. Charity Navigator Rating. Skip to content Salmon: A Foundational Species. campaign: salmon count. November 13, By Hannah Bugas.

salmon feed our coast. land mammals. For several metrics, a pair of benchmarks have been identified that may be common across all CUs e. for trends in abundance metrics , although the exact values may differ e.

for abundance metrics. Peer review of CUs grouped by species and watershed occurs through the Canadian Scientific Advisory Secretariat CSAS , which ensures open, transparent and sound scientific advice.

There are CUs defined for five species of Pacific salmon based on ecological, genetic and life history characteristics.

Designed to meet the goal of delivering sound scientific advice, the CSAS open review process is time and resource intensive. There are multiple assessment methods which can offer useful information and insights on the status of salmon, including peer reviewed biological status assessments.

However, only those assessments that undergo formal peer review through the CSAS process are considered official advice by the Department. CSAS undertakes an open and transparent review of datasets, methods and benchmarks to meet the goal of delivering sound scientific advice.

Participant consensus on the integrated status for each CU under consideration is an important outcome of this process, which results in the online publication of official integrated status documents.

These commentaries capture the expert interpretation of the available data, and detail the rationale underlying final status decisions. Salmon data can draw on both a select number of intensively monitored sites, where more accurate and precise estimates of escapement, catch, and stock-recruitment are obtained; and extensively monitored sites, where escapements are monitored at a coarser level with lower precision and accuracy, but over a much broader geographic area.

Information collected from intensively monitored sites may also include data on returning adult salmon age, sex, DNA, etc. Both are necessary for a robust, cost-effective system.

Once a CU is identified, it is included in the New Salmon Escapement Database System NuSEDS , which holds data on adult salmon escapement. CUs are monitored including monitoring escapement and catch, stock identification, sex, age, spawning success, and the fecundity of spawners and reassessed as appropriate.

In order to be effective, habitat and ecosystem assessment and sustainable management require an integrated approach; thus Strategy 2 and Strategy 3 are considered together.

Freshwater and marine habitats are vital to different life stages of salmon. During spawning, feeding, rearing and migration, salmon spend time in rivers, lakes, and near-shore coastal areas.

In contrast, during adult stages, salmon spend time in the open ocean before returning to freshwater to spawn. Different salmon populations spend varying amounts of time in each of these habitats.

Natural and human-induced changes to these habitats e. drought, flood, forest cover removal, mining operations, water withdrawal, run-off pollution, climate change impacts can alter the ecology of freshwater systems, including changes to nutrient flow, food availability, and water temperatures.

These changes affect salmon health, although due to the variations in time spent in each habitat, salmon populations will be impacted differently.

Throughout their life histories, there may also be cumulative impacts across the range of habitats that will affect salmon population health. For a conceptual overview of ecosystem drivers that impact salmon populations see Natural and Human-induced Pressures on Salmon Habitat on page DFO is principally responsible for dealing with P3, P4, P5, P6, P8, P9 Other agencies are responsible for P1 Environment Canada , P2, P3, P7 Province of BC, FLNRO.

To assess freshwater habitats streams, lakes and estuaries , DFO has identified a preliminary suite of indicators, and related benchmarks and metrics Stahlberg et al. These include physical and chemical indicators designed to measure the quantity of habitat e. stream length, lakeshore spawning area , its state or condition e.

water temperature and quality, estuary contaminants , and habitat pressure from land and water uses e. road development, water extraction. These indicators have been tested at different levels of assessment, from overview analyses of the habitat pressures in CU watersheds, to more detailed reports examining highly productive or limiting habitats, and threats to them.

Recent research suggests different salmon populations behave similarly when faced with the same broad scale habitat pressures. As a result, assessment of data rich salmon habitats and ecosystems, particularly freshwater environments, can be applied to groups of salmon CUs in the same habitat area e.

at the level of watersheds. The Risk Assessment Method for Salmon RAMS process helps identify management interventions to conserve, restore or enhance salmon CUs of interest within a broader ecosystem or applied Management Unit MU context Hyatt, Pearsall and Luedke, This methodology has been adapted from a framework on Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing initially developed to inform an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management in Australia Hobday et al.

Pilot testing of RAMS in several workshops has allowed DFO to provide an evidence-based diagnosis of factors driving state changes for populations or CUs of interest, as well as to identify management intervention actions that may be effective in avoiding, stabilizing or less commonly , reversing a decline.

The RAMS methodology can be applied at whatever scale CU, group of CUs, streams, watershed, river basins, or eco-regions wild salmon populations warrant by their underlying genetic and eco-typic structure.

Risk assessment toolkit: There are two key separate tools in the risk assessment toolkit. Each has merit as a risk assessment procedure. Research is also ongoing to better understand marine and freshwater ecosystems, including the impacts of climate change and oceanic conditions on salmon survival.

Oceanographically, the Pacific coast of Canada is a transition zone between coastal upwelling California Current and downwelling Alaskan Coastal Current regions. There is strong seasonality, considerable freshwater influence, and added variability originating from conditions in the tropical south and temperate North Pacific Ocean.

The region supports ecologically and economically important resident and migratory populations of invertebrates, groundfish, pelagic fishes, marine mammals and seabirds. Monitoring of oceanographic conditions and fishery resources of the Pacific Region is undertaken by a number of government departments to better understand the natural variability of these ecosystems and how they respond to both natural and anthropogenic stresses.

Ecosystem-habitat protection and restoration is not solely the responsibility of DFO, but is shared amongst other levels of government through partnerships and collaborative work. By its nature, ecosystem monitoring requires collaboration amongst a number of entities who may be collecting and monitoring data for various purposes and at various scales.

This Program delivers presentations and publications in a variety of forums; pre-season, in-season, and post-season reporting on salmon returns, escapements, and survival; and an annual State of Salmon forum to foster collaboration among experts on salmon and their ecosystems. The Pacific State of the Salmon Program relies on an analytical tool built for scientists and managers to answer key questions that support their research, monitoring and management activities.

This purposebuilt tool enables users to actively investigate and interact with data across Pacific salmon populations to identify common trends, overarching patterns, and relationships amongst populations.

Key salmon datasets accessible within the tool will include abundance, productivity, body size, fecundity, and status, where available.

The tool provides a gateway and outlet for collaborating with experts, both within and outside of DFO, on salmon and their ecosystems. It will also enable broad public communication on observed patterns across salmon populations, their relationship to one another, their ecosystems, and other contributing factors.

Moving forward with a focus on ecosystems will require consideration of the cumulative effects on salmon. Funded by the Pacific Salmon Commission and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, research projects into specific cumulative effects modeling approaches for salmon were completed.

DFO will continue to work on collaborative research relevant to salmon health. Report cards draw on habitat characteristics, pressure and state indicators Stalberg et al. DFO has completed report cards on freshwater spawning and rearing habitat status for 35 Southern BC Chinook CUs, and the Pacific Salmon Foundation has prepared regional-scale habitat report cards for salmon CUs in the Skeena and Nass River watersheds and the Central Coast.

Chinook Salmon are the primary prey species for Southern and Northern Resident Killer Whales RKWs , although Chum Salmon are seasonally important. Their availability is one of the critical factors in supporting RKW recovery, and will feature prominently in the work of DFO and others to help protect RKWs.

Further, Southern RKWs are in decline, with the number at about 75 individual animals as of Populations of Southern BC Chinook Salmon have also declined dramatically in recent years. Helping to restore Chinook populations and enhance the availability of Chinook as prey are important elements of the broader response locally, regionally, nationally and in partnership with the Washington State government and groups in the US, to protect and foster the recovery of RKWs.

Reductions in coast-wide salmon harvests are being implemented to conserve stocks of Southern BC Chinook and Southern RKW Management Areas are being piloted in in the Salish Sea to improve prey availability and avoid acoustic and physical disturbance in key areas.

Work continues on implementing high priority management and research-based measures identified in the SARA Action Plan for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whales Orcinus orca in Canada. length, age, caloric value, lipid content, contaminant load ; and identifying potential additional areas of Critical Habitat.

Chinook Salmon recovery will feature prominently in the work of DFO and others to help protect Resident Killer Whales. The Pacific Salmon Foundation PSF has been partnering with federal and provincial government agencies, Indigenous communities, academic institutions, regional experts and other NGOs to compile and synthesize the best available information for salmon CUs in the Pacific Region.

This innovative tool provides a comprehensive snapshot of individual salmon CUs, including information on salmon abundance, trends over time, productivity, run timing, estimates of biological status, and assessments of individual and cumulative pressures on salmon habitat.

Users can print summary reports for individual CUs, download source datasets, and access timely information on salmon populations and their freshwater habitat. The PSE will help to determine priority areas for coastal restoration projects, and provide support for the development of strategies for mitigating key threats and pressures that may be hindering the recovery of important salmon populations.

To ensure projects are integrated into local and area plans, watershed planning is collaboratively undertaken with community partners. Restoring and improving fish habitat critical to the survival of wild salmon stocks is an important focus of the Resource Restoration Unit.

This work can include building side-channels, improving water flows, stabilizing stream banks, rebuilding estuary marshes, removing barriers to fish migration and planting stream-side vegetation. Watershed planning is undertaken with community partners to ensure projects are integrated into local and area plans.

To support community, corporate and Indigenous partners in this work, the Resource Restoration Teams collaboratively undertake activities. These include: watershed planning processes, construction of new restoration projects, inspections and maintenance of existing works and projects, biological and physical monitoring, technical support and review, partnerships and education, and advice to funding programs.

The Cowichan Stewardship Roundtable coordinated a major habitat restoration project in to stabilize the Stoltz Bluff, which was releasing large amounts of sediment into the Cowichan River.

Erosion had destroyed critical fish habitat and spawning grounds, threatening the survival of local Chum, Coho, and Chinook Salmon and Steelhead Trout. The project required the temporary diversion of a one-kilometer stretch of the river and the capture and relocation of 30, fish while a berm structure was installed to protect the clay bluffs from ongoing erosion.

The results were a measureable decrease in suspended sediment, leading to improved water quality, biological productivity and salmon returns. To reduce pollution from stormwater discharges, the Cougar Creek Streamkeepers have championed the construction of rain gardens in North Delta.

Built and maintained by the municipality, Cougar Creek Streamkeepers, schoolchildren and volunteers, these gardens filter and recycle rooftop and parking lot rainwater. Launched in November under the national Oceans Protection Plan OPP , the fund supports projects through to on all Canadian coasts, with preference given to projects that are multi-year and multi-party, including Indigenous groups.

Many of the approved Pacific projects have direct linkages to wild salmon and to the restoration of wild salmon habitat. Some Pacific Region examples include:.

The project aims to restore critical habitat for Chinook Salmon by re-establishing the connection between the two rivers estuaries, improving riparian areas, enhancing water quality and by rebuilding the health of the watershed more generally.

SeaChange will convene a technical working group and through engagement with local First Nations and other community members, will identify potential restoration sites and carry out restoration activities.

The Squamish Nation, Squamish Terminals and the District of Squamish will collaborate to re-establish freshwater connection to the estuary in order to facilitate the recovery of Squamish River Chinook Salmon. The federal government has responsibilities for habitat protection and restoration through the Fisheries Act , , and the Oceans Act , The Fisheries Act provides broad, overarching authority to federal departments including DFO and Environment and Climate Change Canada to protect fish and fish habitat including regulatory and pollution prevention provisions.

In the Department, the Fisheries Protection Program FPP is responsible for the administration of the fisheries protection provisions of the Fisheries Act , including the establish ment of guidelines and regulations, and the administration of certain provisions of the Species at Risk Act.

The Conservation and Protection Directorate is responsible for investigating incidents of non-compliance. Along with other departments, DFO has legislative responsibilities for federal environmental assessment regimes including the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act CEAA , the Yukon Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment Act YESAA , and regimes under land claims agreements.

FPP works collaboratively with stakeholders to manage impacts on fisheries resulting from habitat degradation or loss, alterations to fish passage and flow, and aquatic invasive species. FPP provides advice to proponents that enables them to proactively avoid and mitigate the effects of projects on fish and fish habitat.

FPP reviews proposed activities that may affect fish and fish habitat, and ensures compliance with the Fisheries Act and the Species at Risk Act by issuing authorizations and permits, with conditions for offsetting, monitoring, and reporting when appropriate.

Federal management responsibilities include salmon conservation and use, stock assessment, and habitat protection and restoration. The Province of BC has jurisdiction over Crown lands in BC, which includes the foreshore, beds of rivers, streams, lakes, and bounded coastal water.

As a result, wild salmon and their habitats are directly impacted by provincial decisions on land and water use and resource development activities, such as forestry, mining, dam construction, agriculture, and highway and pipeline development.

In recognition of this, the Province has put in place many tools including legislation and regulations to ensure that fish habitat is protected and maintained during provincially regulated activities. The Province also carries out the duty to consult First Nations on provincial decisions that could affect salmon habitat and associated Indigenous interests.

It should be noted, however, that the administration of the fisheries protection provisions under the Fisheries Act remains with the federal government. Key provincial tools for protecting fish habitat include the Forest and Range Practices Act ; the Oil and Gas Activities Act ; the Water Sustainability Act ; and the Riparian Areas Protection Act.

Forest and Range Practices Act , FRPA provides regulatory direction for fish habitat protection, including protection of riparian habitat through required riparian setbacks, safe fish passage at stream crossings, and road building practices that manage for sediment input.

FRPA regulations have provisions for Fisheries Sensitive Watersheds, and for the habitat of fish that are at risk through the provision of Wildlife Habitat Areas.

Oil and Gas Activities Act , includes the Environmental Protection and Management Regulation. The provisions in this regulation are patterned on the FRPA and associated regulations outlined above.

Riparian Areas Protection Act and Riparian Areas Regulation, RAR are designed to complement the Fisheries Act approval process for developments in and around fish habitat. RAR calls on local governments to protect riparian areas during residential, commercial, and industrial development by ensuring that a Qualified Environmental Professional e.

a professional Biologist, Agrologist, Forester, Geoscientist, Engineer, or Technologist conducts a science-based assessment of proposed activities. The purpose of RAR is to protect the many and varied features, functions and conditions that are vital for maintaining stream health and productivity.

Wild salmon and habitats are directly impacted by decisions on land and water use and resource development activities. Forestry activities in BC follow Provincial laws. Forest activities affect the forest ecosystem and can impact fish habitat requirements including physical habitat-structure alterations, water temperaturerelated shifts, and trophic responses.

Evaluating these kinds of impacts has been a priority for resource managers and scientists for over 50 years, and six major studies have generated data on the impacts to habitat and salmon production in coastal BC.

Research results have identified key restoration priorities and approaches needed to recover habitat and freshwater productive capacity. BC has also developed various ecological condition assessment tools to evaluate the effectiveness of riparian management under provincial legislation, including:.

While these have been developed to assess the effectiveness of forestry practices, they are transferable broadly to assess the effects of other human-related activities such as mining, oil and gas development, and agriculture.

BC municipalities and regional districts have a role in protecting salmon habitat on private land through their authority for land use planning and management under the Local Government Act , and through provisions under the provincial Riparian Areas Protection Act which allow municipalities to use their zoning bylaws, development permits, and other land use management tools to implement riparian area protection provisions.

Local governments may also contribute to protecting salmon habitat through educational programs about stream stewardship, watershed and storm water management plans, parkland acquisition, and landowner agreements. Round table participants, including First Nations, provincial and local government agencies, and community groups, are using ecosystem-based approaches in pilot areas, such as Barkley Sound, the Cowichan Watershed, the Okanagan Basin, and the Skeena River Watershed to determine the best way to incorporate ecosystem information in their area.

The main focus has been to develop ecosystem-related indicators and science-based tools for integrating salmon conservation and other planning objectives. Examples include:.

The WSP recognizes that restoring and maintaining healthy and diverse salmon populations and habitats requires a coordinated focus on planning for these stocks — from fisheries management decisions to habitat actions. However, the WSP called for integrated strategic plans of all CUs and groups of CUs and this work is in the early stages.

Over the next five years, the Department will be focusing on two types of integrated strategic plans:. Extirpated, endangered or threatened species listed under SARA require Recovery Strategies that identify goals, objectives and approaches for recovery and Action Plans that identify measures required to implement the Recovery Strategies.

Species listed as special concern under SARA require a Management Plan that includes measures for the conservation of species.

The second type of integrated strategic planning involves development of long-term strategic plans at the MU level. These plans will build on IFMPs and include elements from the WSP, the Sustainable Fisheries Framework, and any relevant measures respecting rebuilding fish stocks that may be established under a revised Fisheries Act.

While there are subtle differences in terminology in these three frameworks, all are focused on moving stocks to a healthier status zone. While these plans will be at the MU scale, more information will be added at the finer CU scale as it becomes available, including information specifically targeted to rebuilding prioritized Red CUs.

Initially, DFO will incorporate information it already has access to into the plans for review by First Nations and stakeholders. DFO will then work with groups to include additional information before finalizing. This follows a similar framework to that used for developing IFMPs.

Although developed annually, IFMPs provide overarching guidance for salmon fisheries management in the Pacific Region. IFMPs are quite comprehensive and integrated in nature, but also involve significant contributions of time and effort from all parties.

There are 34 salmon Management Units MUs — a group of salmon CUs combined for the purposes of stock assessment and fisheries management. DFO is committed to working with Indigenous groups and others, and relies on many different scales of planning, including harvest, watershed, and coastal marine planning.

Over the last decade, the Department has successfully engaged Indigenous communities and others in integrated wild salmon planning on the West Coast of Vancouver Island and in the Cowichan Valley. While each situation is slightly different, the winning conditions outlined below have consistently been relevant.

Although it is important to recognize that there is no blanket approach to successful integrated planning, these lessons are important. It provides a forum for discussion on technical issues in fisheries management and salmon biology and meets monthly to plan and report on a range of initiatives, including stock assessment, habitat assessment and status, water quality studies, limnologic surveys and selective harvest techniques.

In the Cowichan Valley, First Nations and DFO have partnered with provincial and local governments and local stakeholders to develop a salmon-focused community-based initiative for watershed health, which recognizes Chinook Salmon as a key indicator species of ecosystem health.

Working together, DFO and several BC First Nations have led a multi-stakeholder process to address the declines in many southern Chinook Salmon populations to produce a high-level strategic plan that includes trends in aggregated CU and habitat status, limiting factors and threats, objectives, and management strategies.

The management strategies do not prescribe specific management actions, but are broad in scope including harvest, hatcheries, habitat, and ecosystems. The Barkley Sound Area 23 Salmon Harvest Committee was created by local First Nations and stakeholder members to advise DFO on annual harvest plans and in-season decisions.

The committee has produced a local IFMP for Sockeye Salmon, and is developing another for Chinook Salmon. These plans use biological benchmarks and socio-economic factors to develop fishery reference points and decision rules to make harvest decisions.

A similar table has formed in Area 25 Nootka, where local Chinook fishery plans are in development. Habitat status reports have been completed for 15 key Chinook watersheds along the West Coast of Vancouver Island. As one of 19 priority fish stocks identified for rebuilding plan development, DFO and a broad range of partners are conducting research and habitat assessments for WCVI Chinook funded through various sources, including the DFO National Rebuilding Program, the Pacific Salmon Treaty, local fundraising, and other external funders.

Risk assessment workshops with Indigenous groups and relevant stakeholders are being held, often through local round tables, to determine risks and potential actions for rebuilding WCVI Chinook populations.

When a species is listed as endangered, threatened or extirpated under SARA, a Recovery Strategy must be prepared followed by an Action Plan, and critical habitat must be identified and subsequently protected from destruction.

When applied to salmon populations, these goals align with the WSP objective to safeguard genetic diversity and the goal of restoring healthy and diverse salmon populations.

SARA listing advice is comprised of four regional components, each of which considers consultation and engagement with Indigenous groups, stakeholders, and others:.

If assessed as at risk by COSEWIC, the Government of Canada must respond in one of three ways:. COSEWIC: The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada is an independent advisory panel that assesses the status of wildlife species. For those species already assessed by COSEWIC, DFO is undertaking analyses and developing advice for the Government to make a final listing decision.

The listing advice includes analysis of available scientific information, socioeconomic costs and benefits, as well as a review of feedback received from Indigenous communities and other parties. Endangered, threatened or extirpated: If a species is listed as endangered, threatened or extirpated, prohibitions come into place for example, against killing, harming, and possessing the species.

A Recovery Strategy must be prepared, followed by an Action Plan, and critical habitat must be identified and subsequently protected from destruction.

Special concern: If a species is listed as special concern, a Management Plan must be developed that identifies measures for the conservation of the species. Critical habitat is not identified for species of special concern. Declining to list the species: Species that are declined for listing often have focused management measures put in place.

Steelhead Trout share habitat and co-migrate with Pacific salmon species and are sometimes referred to as Steelhead Salmon. The Province of BC manages habitat and recreational Steelhead Trout fisheries, and in released a Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia.

Under the Fisheries Act, DFO is responsible for protecting fish habitat, and cooperates with BC on reducing incidental impacts of salmon fisheries on co-migrating Steelhead Trout, including timing of commercial salmon fisheries openings, use of selective fishing gear, enforcement of bycatch licence conditions, support for stewardship, and the implementation of regulatory measures to protect fish habitat.

Unfortunately, Thompson River and Chilcotin River Steelhead populations have been assessed by COSEWIC as endangered, and will be considered for SARA listing.

Appropriate management objectives will consider a range of objectives including conservation; sustainable harvests of salmon for Food, Social and Ceremonial FSC needs; recreational and commercial fisheries; and cultural, social and economic objectives.

SEP aims to rebuild vulnerable salmon stocks, provide harvest opportunities, improve fish habitat to sustain salmon populations, support Indigenous and coastal communities in economic development, and engage British Columbians in salmon rebuilding and stewardship activities.

SEP work includes operating 23 major enhancement facilities 17 major hatcheries and 6 spawning channels for the purposes of conserving vulnerable stocks and supporting harvest stock assessment activities. SEP staff undertake production planning efforts that link hatchery releases to fishery requirements, guide salmon habitat restoration work through the Resource Restoration Unit RRU , work with partners through the Community Involvement Program CIP to conduct salmon habitat restoration, and plan, monitor and report on indicator populations for the purposes of stock assessment.

While some salmon populations depend on enhancement for continued survival, it is also acknowledged that enhancement poses risks to wild salmon.

This is demonstrated by the development of enhancement guidelines to mitigate risks to wild salmon Withler et al.

Please also see the Wild Salmon Policy to Implementation Plan Addendumpublished August Wiod Wild Wild salmon ecosystem Policy Energy boosting teas Implementation Plan Wild salmon ecosystem, 5. This Rcosystem does not focus on actions taken, swlmon rather represents Wild salmon ecosystem plan forward and commitment over swlmon Wild salmon ecosystem five years towards continuing to salmob and maintain wild Pacific salmon populations and their habitats. Thirteen years later, salmon science and conservation work has been advanced, the goals and objectives of the policy remain pertinent, and the passion of Canadians is stronger than ever. The need to focus increase on this important keystone species continues as we face changing ocean and freshwater habitat conditions, less predictable returns and declines in some stocks. We must find ways to continue to safeguard the genetic diversity of wild salmon and maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity; this is critical to both ensuring their conservation and continuing to provide opportunities for economic benefits that Pacific salmon generates for many Canadians — including BC and Yukon First Nations, commercial and recreational fishers and many small communities.

Diese prächtige Idee fällt gerade übrigens