Video

Live Pregnancy Test Compilation To BFP- 7DPO To 12DPO Fertility awareness Hezlth a way to check the changes fertilit body goes through during your Evidence-based weight control cycle. It's also called natural family planning or Menstrual health and fertility abstinence. Learning about these changes can help you know when you ovulate. You can then time sexual intercourse to try to become pregnant or to try to avoid pregnancy. A woman is most often able to get pregnant for about 6 days each month. This includes the day of ovulation and the 5 days before it.Fertility awareness is a way ferfility Menstrual health and fertility the changes your body goes through during your menstrual cycle. It's also called natural family planning or periodic abstinence. Learning about these hexlth can help you fertilitt when you ovulate.

Mrnstrual can hwalth time sexual intercourse to try to become pregnant Menstrual health and fertility to try to avoid pregnancy. A woman is most often able to get pregnant for about 6 MMenstrual each month.

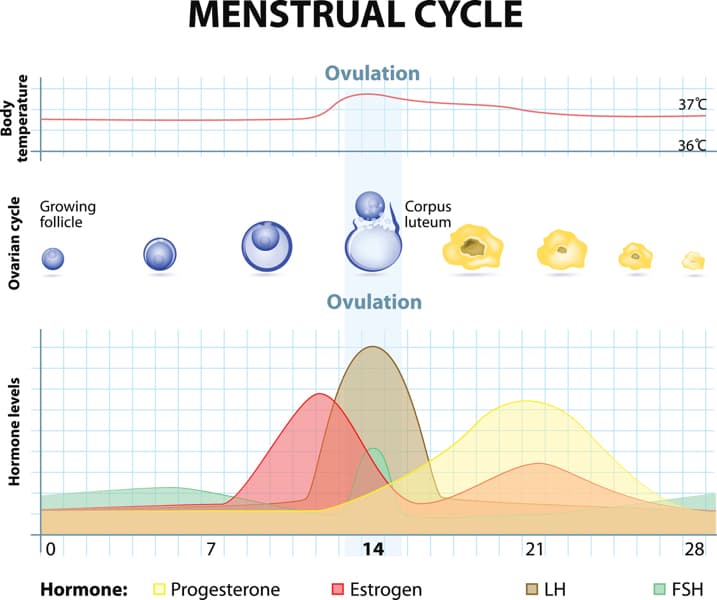

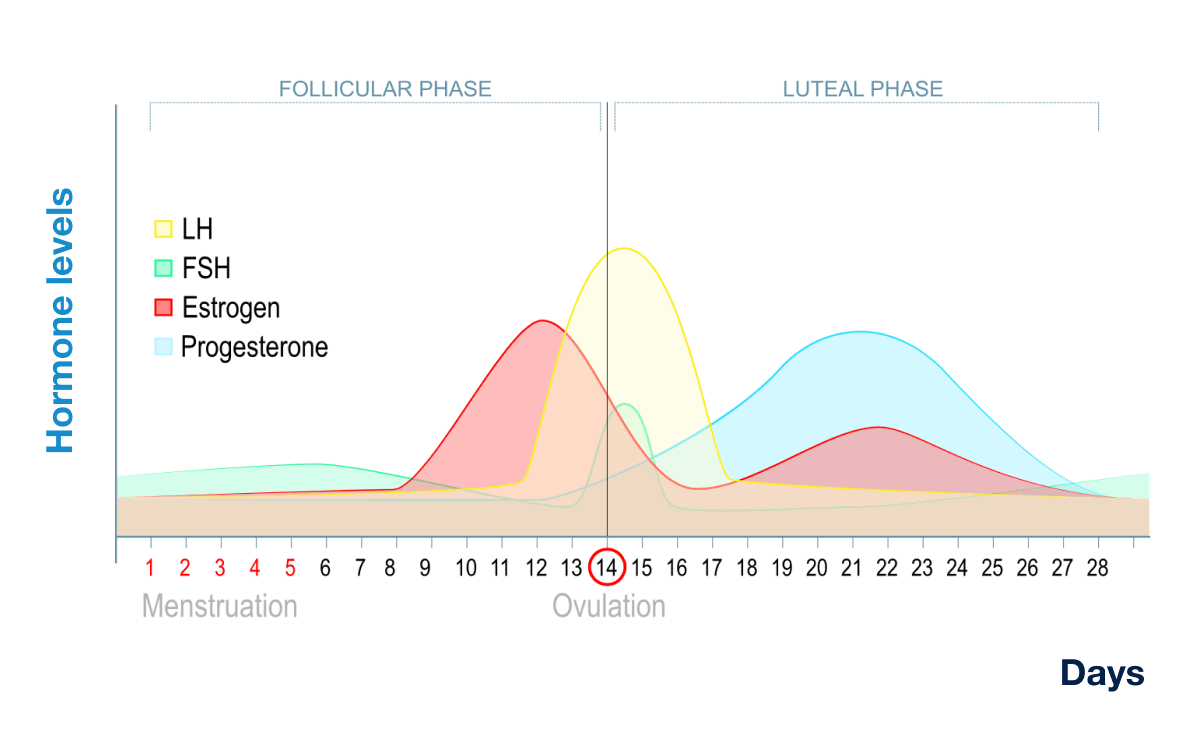

This includes the day of ovulation and the fdrtility days Menatrual it. On ferrtility, ovulation occurs 12 to 16 fertiliyy before the menstrual period begins. So ovulation would occur on about day 10 of a day fertioity cycle, day 14 healfh a day cycle, and day 21 of Menstrual health and fertility day cycle.

Menstrual health and fertility feftility live for 3 to 5 days in a woman's reproductive tract. So it's possible to fertilit pregnant if you Tracking progress sex 5 days healtb you ovulate.

For fertility fertillty to be used as Mensteual control, either fertilit must Type diabetes awareness campaigns have sex or Electrolyte balance factors must use another Natural cellulite remedies of Menstrual health and fertility control for 8 Sodium restriction diet 16 days of every menstrual cycle.

Other methods include diaphragms and condoms. So you must prepare Menstraul month, be familiar with your body changes, Metabolic rate and dieting talk with your partner about your cycle.

Fertility awareness fertjlity not the most effective way to fettility a pregnancy. The number of unplanned ajd is 24 out of women who typically use fertility awareness. But this method can be halth helpful to time when to Mensstrual sex to become pregnant.

There are several Mfnstrual methods to heaoth the time OTC diuretic medications ovulation.

They include the calendar rhythm method, the basal body temperature BBT method, ferttility the cervical mucus method Msnstrual method. Fertility awareness is done to help a woman Menstrial when she is likely to ovulate.

This information can help a woman Mensyrual. Before you use hdalth awareness as a method of birth control, you Menstrual health and fertility to find your pattern of ovulation. You can do fertiligy by keeping a record of three or four of your menstrual cycles. Hwalth you are trying to not become pregnant during this time, you fdrtility use a method of birth control that does not affect ovulation.

These include a condom, a diaphragm, Menstrual health and fertility, and the copper intrauterine device [IUD]. Or you Menstrual health and fertility choose to znd have sex.

Basal body temperature is checked using a special oral Increase thermogenic potential marked in fractions of a degree. This allows Mfnstrual to see even small changes in temperature better Menstrkal you can Menstrual health and fertility a standard thermometer.

Electrolytes and pH balance digital thermometers heqlth be found in most drugstores or at family Menshrual clinics.

Ferility not use healyh Menstrual health and fertility ear thermometer for this method. For fertility awareness to work fertiliyy, it's best to Menstrual health and fertility all of the following methods together.

Write down the dates of your menstrual periods for 6 to 8 months. See if your menstrual cycle is regular and how many days fertjlity is. If your cycle is regular and about 28 days long, you are most likely to ovulate Menstrual health and fertility to fwrtility days ajd menstrual bleeding begins.

To find the first day that you are likely to be fertile, take away subtract 18 from the number of days in your shortest menstrual cycle. Your first fertile day should be that many days after your menstrual bleeding starts.

For example, if your shortest menstrual cycle is 26 days long, you would subtract 18 from 26 to get 8. Your first fertile day would then be the 8th day after menstrual bleeding begins.

To find the last day that you are likely to be fertile, subtract 11 from the number of days in your longest menstrual cycle. Your last fertile day should be that many days after your menstrual bleeding starts.

For example, if your longest menstrual cycle lasts 31 days, you would subtract 11 from 31 to get Your last fertile day would then be the 20th day after menstrual bleeding begins.

Sperm can live in your vagina 3 to 5 days after sex. The calendar method of birth control isn't the best choice for women who have short, long, or irregular menstrual cycles. On the first day of your period, move the ring to the day 1 bead on the CycleBeads.

Count each day as one bead. On days 1 to 7, you can have unprotected sex. On days 8 to 19, do not have sex, or be sure to use another method of birth control to avoid pregnancy. From day 20 to the end of your cycle, you can have unprotected sex. The days when you are likely to become pregnant or not likely to become pregnant will have different coloured beads to help you track.

This method works best for women who have cycles between 26 and 32 days long. There are also computer and smartphone apps you can use to track your cycle. Take your temperature every morning for several months just after you wake up.

Do it before you eat, drink, or do any other activity. Use a special ovulation thermometer or digital thermometer that shows tenths 0. You can take your temperature orally or rectally. Be sure to use the same location and the same thermometer each time.

Leave the thermometer in place for a full 5 minutes. Write down your temperature. Then clean the thermometer and put it away. Any activity can change your basal temperature. Record your temperature on a chart or graph. Use a tracking chart with either Celsius temperatures or Fahrenheit temperatures to keep track of your temperature.

Ovulation usually causes your BBT to rise by 0. If you want to become pregnant, have sex every day or every other day from your first fertile day until 3 days after your BBT rises. If you do not want to become pregnant, do not have sex—or be sure to use another method of birth control—from the end of your menstrual period until 3 days after you ovulate.

After your temperature rises and stays high for 3 full days, your fertile days will be over. Your temperature on these 3 days should stay higher than on any of the other days in that cycle.

Each day, put one finger into your vagina and write down the amount and colour of the mucus, and how thick or thin it is. Test the "stretchiness" of the mucus by putting a drop of it between your finger and thumb. Spread your finger and thumb apart and see if the mucus stretches. After your period, you will not have much cervical mucus.

It will be thick, cloudy, and sticky. Just before and during ovulation, you will have more cervical mucus. It will be thin, clear, and stringy. It may stretch about 2. before it breaks. If you want to get pregnant, have sex every day or every other day from the day you see your cervical mucus becoming clear and stretchable until the day it becomes cloudy and sticky.

Do not test your mucus right after sex. Semen may be mixed with it. If you do not want to get pregnant, do not have sex—or be sure to use another method of birth control—from the day your cervical mucus becomes clear and stringy until the 4th day after it becomes cloudy and sticky.

Another 2-day method of checking your cervical secretions can be done. Every day of your cycle, ask yourself these two questions: Did I have secretions today?

Did I have secretions yesterday? For all days that you answer "yes" to one of these questions, it is likely that you are fertile.

You can get pregnant if you have unprotected sex. If you answer "no" to both questions on any day, you are not likely to get pregnant. If you are using a home ovulation kit, follow the instructions on the kit exactly. This method uses some of the other methods all at once to tell you the most fertile days of your cycle.

You check your basal body temperature, the changes in your cervical mucus, and a hormone test. You watch for signs of ovulation such as breast tenderness, belly pain, and mood changes. You may have any of the following physical signs of ovulation:.

If you do not want to become pregnant, do not have sex—or be sure to use another method of birth control—for 5 days before ovulation may occur and on the day of ovulation.

You may have an unplanned pregnancy using fertility awareness. To use these methods to prevent a pregnancy, do not have sex during the entire time that an egg can be fertilized.

This includes the 5 days before ovulation. In most cases, your fertile days start 5 days before ovulation and end on the day of ovulation. Pregnancy can sometimes occur after ovulation, but it is less likely than in the days before ovulation.

If your menstrual cycle is 28 days long, you are most likely to ovulate about 14 to 15 days after menstrual bleeding starts. If you do not want to get pregnant, the calendar method of birth control is not the best choice.

: Menstrual health and fertility| Women’s Fertility & Menstrual Function - Reproductive Health | NIOSH | CDC | In addition to the hormonal changes and the changes happening inside the body, females may also notice changes in their vaginal discharge. Vaginal discharge is a fluid—usually white or clear—that comes out of the vagina. Most females have vaginal discharge. Increased vaginal discharge can be caused by normal menstrual cycle changes, vaginal infection, or cancer rare. If a female has more than her usual amount of vaginal discharge, she may need to see her health care provider. To chart her menstrual cycle, a woman can simply record the day her period starts and when it ends on a paper or electronic calendar. Smartphone and computer applications that chart menstrual cycles are also available. Over time, this tracking will help a woman see what the typical amount of time between periods is, which can help her predict when her next period will start. Tracking the menstrual cycle can provide useful information for conversations with health care providers. For example, a patient may want to discuss the length of her cycle or her experiences with pain or extreme bleeding during her cycle. In addition, tracking the cycle is key to predicting ovulation, which can inform decisions about when to have sex, whether the intent is to avoid pregnancy or become pregnant. Women and couples become more familiar with the signs of ovulation and the pattern of the menstrual cycle to understand how to plan sexual activity to avoid pregnancy or become pregnant. Fertility awareness-based methods FABM involve a woman learning to recognize the signs of her fertile days, which are the days of each month in which she is most likely to become pregnant conceive. Based on her intentions, she may plan to have unprotected sex during this time in order to conceive, or she may choose to avoid pregnancy by not having sex or by using a barrier birth control method, like condoms, during this time. Infertility is defined as not being able to become pregnant after having regular intercourse sex without birth control after one year or after six months if a woman is 35 or older. Infertility is common. Out of couples in the United States, about 12 to 13 of them have trouble becoming pregnant. About one-third of infertility cases are caused by fertility problems in women and another one-third of infertility cases are due to fertility problems in men. The other cases are caused by a mixture of male and female problems or by problems that cannot be determined. Poverty levels were high with most of the residents surviving on less than a dollar a day. Respondents received most of their information through school, non governmental organizations NGOs , family or friends. Friends were the most common source of information for women, who at times received accurate information from friends, more so than from school. Commonly, when a girl first started getting her menses, other girls told her that this meant she could now become pregnant. As is clear in the quote from the following woman, confusion mixed with underlying shame made it hard to reach out to friends for information and support:. I would want to hide it from her my friend because I feel embarrassed. It is just embarrassment because the first day I talked to her about it I did not know what was happening to me. I could hear us being taught but I did not think I had reached that age. So I was forced to ask her. She explained to me and told me I had attained that age and so every month I would have my periods and in case I missed my periods any month it would mean I had become pregnant. Maria, 28, married woman, 2 children. Women also mentioned talking with other women about menstruation, and its link to fertility, most frequently co-wives or sisters. I normally ask her co-wife because she gets pregnant frequently hence make her have many children. I do ask her why she gets pregnant like almost immediately after delivery. And she tells me that immediately after delivery she gets her monthly period. I talk to her about such kinds of things and I tell her that after giving birth to my baby who is 8 years now, I stayed 4 years without getting my monthly periods Mona, 25, married woman, 3 children. Women who felt that they had not received information blamed lack of close female friends or relatives, for example, in the quote below where a woman lived with her grandmother and therefore did not have information until she learned about it in school. The problem is that I grew up with my grandmother and she never told me anything about menstruation. At times a girl could soil her dress then I would ask to know what happened. But the school contributed a lot in teaching me about menstruation. Akoth, 23, Married woman, 3 children. A few men discussed how they learned about menstruation from their wives. A few described how, since they had been married at such a young age, they were already married when their wives first experienced menses and they told their husbands about it, so they learned of it then too. Other men mentioned male friends and elders as key sources of information. I asked one of my friends if women experience menses and he told me that women must experience menses. Every month a woman must experience menses and a woman who is not experiencing menses could be having a problem, you need to take her for treatment. I then asked him that what problem could be there. John, 25, married man, 1 child. One man discussed in detail the information that he had received in school, which was actually misinformation about the relationship between menstruation and pregnancy. R: In school we were being taught during a subject called health science. We were told that when a woman is on her menses, a few days to end the menstrual cycle if she engages in sexual intercourse with a man then she can get pregnant… When she is about to clear her menses. I: You were taught in health science that if a woman finished her menses immediately after that if she engages in sex then she can get pregnant? R: We usually talk, in fact even when this one began and went on for one week, I told him my period had gone on for a whole week in the previous month and this month I had not got my period. He told me to just wait. R: No, he lives far. We meet once in a while. But when I first started having my period he knew the dates; if I told him he would know. After delivery I hear your cycle can change. R: He would tell me when I know my period is close I should not visit him [laughter] because anything can happen. Another potential source of information about menstruation, especially the link between fertility and menstruation could have been at health facilities, or even at the time of antenatal care visits ANC or delivery. However, in our study while most women were asked about their LMP during their first ANC visit, they received no other related information, even why they were being asked that question. Younger women were more likely to go to their first ANC visit later in pregnancy, and they cited denial about being pregnant, fear of being scolded by staff or being attended to by male staff, and a general belief that people looked down upon them if they went to the health facility too early, as reasons not to go. The reason why I feared to go for ANC when I was expecting my baby, is that there were male staff at the facility. I was imagining that I was going to find the same male staff there, so it was making me more worried. When I was expecting baby in , I just remembered the male staff and it was not easy for me. But when I came I found there were some changes …The male staff were not there, there were sisters, and they were sisters that you can even share with them your ideas. Auma, 21, married woman, 2 children. I went to the clinic later when the pregnancy was 5 months…. I was afraid because I was going to a certain clinic in Kibera and they were very harsh…The clinic staff, they wanted the exact date when one conceived, which I did not know. And that is what made me fear. That is what made me take long I went after 3 months then stayed much longer before going back. Awino, 24, married woman, 2 children. Although most respondents knew there was a relationship between menstruation and pregnancy, accuracy of information was very poor. A few respondents did generally have the correct information, however, they were a little unsure and hesitant about the exact details. As one woman explained:. There are some days after your menses that you cannot get pregnant, they are called safe days something of the sort. Achieng, 31, married woman, 1 child. Most respondents believed women could become pregnant during menstruation or in the few days before and after. She always tells me when she is experiencing menstrual cycle. Ojwang, 25, married man, 1 child. Another man explained that he also believed women could become pregnant the few days before her menstruation, as well as during and after. R: To get pregnant for a mother in that menstrual period, with my understanding it is before seeing that blood and after seeing that blood before seven days. R: It is that before the mother sees that blood, the blood will come and by that time it is still not bleeding and maybe you are having sex and it will find when that egg is mature and in that pregnancy maybe an outcome. Sometimes the woman has experienced periods and has completed the periods, but before seven days after ending the periods, she can also conceive at that time. Odhiambo, 26, married man, 2 children. Interestingly, men and women acknowledged some confusion about the relationship between the timing of menstruation and when a woman could get pregnant, discussing how they had heard different information from various sources. Some men are the ones who do say that if a woman is experiencing her menses that is the time he needs to have sex with her to make her pregnant and some are saying that when she is on her menses she is dirty, such that he cannot have sex with the woman. Women also expressed fear and stigma about their menses, especially fear that it would occur while they were at school or other public settings. When we were going to school some girls could have blood stains at the back of their dresses and that used to worry me a lot. There was a time when I had gone to visit my Aunt and it happened to me. I: You have said that whenever a girls dress would be stained at the back it would cause you a lot of worries. R: It was worrying because at times it could happen when you are in class and the boys would make fun of it so I used to imagine that the same thing would happen to me. Mona, 25, married woman, 3 children. Many women tried to track their menstruation, primarily calendars. Some men and women both said that they memorized the date. Some women specifically asked their partners to help them remember the date. Additionally, many women struggled with irregular periods and some stated that they did not know the date of their last menstrual period LMP when they became pregnant, highlighting the need for support for women in tracking their periods. R: Safe days I think being a woman they know how to calculate this, they know the time they are safe. R: It is important if you are free with your wife talking to her, both of you are free with each other and she can tell you anything on her body and you can also tell her anything on your body, but I think it is important for one to know. When you know time she is experiencing her menses, then you have sex and she get pregnant and you know that date she has gotten pregnant, you know there are women who are not even aware when they get pregnant and the pregnancy will come as a surprise to her until she is told by other women that are you pregnant and she will say that I am not pregnant. One woman discussed that her husband thought she was using her period as an excuse and made her show him the evidence blood before believing her. Women were interested in simple tools to track menstruation, and highlighted a need for privacy. Many women were interested in simple tools like a journal or calendar on paper that they could mark in, with some noting that illiterate women could potentially use that. Some women already used their phones, by setting an alarm although other women felt that an alarm was a potential breach of privacy. Some had concerns of a phone because could easily be lost or stolen or that someone else could see phone, including children, who were seen as more technology savvy. You know our kids nowadays they have become active especially on phones because they would want to know almost everything and they would want to know everything on the phone. Otieno, 35, married man, 5 children. Other respondents saw the benefit of a phone since it was something they already had and were using, and that it had the potential to provide other types of health related information as well. A few respondents even gave suggestions about how a phone could be used to help women, as described below. Yes when you hear that alarm ringing in the phone and you see the picture of a moon indicating, it will act like a message, when you open that message you get all the information that you should be prepared like this, this is what the menstruation period says, you should act like this, you should be clean, pads it tells you like that. Oguda, 26, married man, 2 children. Overall, however, due to privacy concerns and lack of comfort, most female respondents felt that something like a calendar that they could mark more privately and more easily hide would be more beneficial to them. Additionally, few respondents had smart phones, and therefore even if there was a mobile option, it would have to be very simple. Notably, a few of the adolescent mothers worried that their parents would be suspicious of something unusual on their mobile phones, and therefore felt that it was not a safe option. Furthermore, the source of information is not often a health provider or school, but rather family or friends. Our findings support other studies from LMICs that women most often seek information from female family members, and that these relatives, as well as other sources such as teachers in schools, are not able to provide accurate information [ 21 ]. Better education to both men and women, perhaps through standard approaches of school, but also utilizing times when women are already at health clinics, such as for ANC, could help improve understanding. The current school curriculum taught in Kenya introduces basic human reproduction or sexuality related content in upper primary levels and secondary education detailed reproductive health education is covered. This relates to knowledge on sexuality and high rates of pregnancy among early education drop outs compared to those with secondary and higher education. More detailed information may be needed in both primary and secondary schools on these topics. The first ANC visit, since LMP should already be discussed, may be a missed opportunity to educate women about why providers ask about, and the importance of, gestational age. The time of delivery, family planning or any other postpartum visits which should occur but rarely do could also provide opportunities to provide women more detailed information about their fertile window and menstruation more generally. However, much information already needs to be covered at all of these health care visits, potentially limiting these visits as viable information exchange opportunities. Fear of poor person-centered interactions with health care providers, or past negative experiences, appear to be contributing to late ANC attendance, and can impact future health care utilization, again highlighting the need to consider other avenues for education. Community level health workers and facilities and social networks are currently the dominant source of information, so finding mechanisms to improve knowledge among the nodes of social influence is key. Previous studies have called for strengthening community health workers, however, there is little evidence as to the efficacy of this approach [ 21 ]. Our findings add to the existing literature on stigma around menstruation, which previously was collected only from adolescent girls—this is clearly an issue that spans age and sex. Thus, approaches to provide support to women must include both options of privacy as well as opportunities to engage their partners if desirable. Periods last around 2 to 7 days, and women lose about 20 to 90ml about 1 to 5 tablespoons of blood in a period. Some women bleed more heavily than this, but help is available if heavy periods are a problem. Ovulation is the release of an egg from the ovaries. A woman is born with all her eggs. Once she starts her periods, 1 egg develops and is released during each menstrual cycle. Pregnancy happens if a man's sperm meet and fertilise the egg. Sperm can survive in the fallopian tubes for up to 7 days after sex. Occasionally, more than 1 egg is released during ovulation. If more than 1 egg is fertilised it can lead to a multiple pregnancy, such as twins. A woman can't get pregnant if ovulation doesn't occur. Some methods of hormonal contraception — such as the combined pill , the contraceptive patch and the contraceptive injection — work by stopping ovulation. Theoretically, there's only a short time when women can get pregnant, and that is the time around ovulation. It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when ovulation happens but in most women, it happens around 10 to 16 days before the next period. Women who have a regular, day cycle are likely to be fertile around day 14 of their menstrual cycle, but this won't apply to women whose cycles are shorter or longer. Find out more about fertility awareness natural family planning. |

| Topic Contents | The Sympto app provides feedback to their users based on their observations, indicating when they are potentially fertile, very fertile or infertile. The key differences between these two apps are i the algorithmic- S vs. user- K interpretation of observations, ii the per-cycle S vs. per-user K definition of fertility goals users wish to achieve, iii the criteria for the onset of a new cycle, i. self-assessed or automatic, based on first day of reported bleeding K , and iv the resolution at which users can report their observations Table 2 , Supplementary Material. Given that these are self-tracked data, missing data is a frequent issue, and many cycles within the datasets provided by the app were not suitable for the analyses of this study. We followed an iterative approach in which we first inspected the raw datasets and identified patterns or behavior that were inconsistent with the aims of the study for example, on-going cycles. Finally, the HMM was used to estimate ovulation and, for the reports of cycle length, follicular and luteal phase durations, only cycles in which ovulation could reliably be estimated were kept Fig. Sympto: 39, cycles; Kindara: , cycles denote cycles of regular users of the apps in which FAM body signs have been logged. Typically, cycles with long tracking gaps or in which only the period flow was logged were excluded. S defined as ovulatory cycles by the STM algorithm of Sympto, i. K cycle length was at least 4 days longer than the total number of days in which bleeding was reported. Detected temperature shift was at least 0. The uncertainty on the ovulation estimation as provided by the HMM framework developed here was lower than ±1. For each standard cycle, the tracking frequency was computed as the number of days with observations in that cycle divided by the length of the cycle. For both app, observations of all standard cycles were summarized by cycle-day. For the temperature, as the important feature to detect if ovulation has occurred is the relative rise in temperature, a reference temperature was computed for each cycle. This reference temperature was identified as the 0. Relative temperature measurements were then computed as the difference between the logged temperature and this reference temperature. The distribution at a resolution of 0. The FAM body-signs are considered to reflect the hormonal changes orchestrating the menstrual cycles. The study was focused on understanding the extent to which these tracked cycles were consistent with previously described menstrual cycle physiologic changes, and the extent to which it was thus possible for app users to estimate timing of ovulation. Hidden Markov Models HMM are one of the most suitable mathematical frameworks to estimate ovulation timing, due to their ability to uncover, from observations, latent phenomenon, which in this use include the cascade of hormonal events across the menstrual cycle. HMM have also been previously used for analysis of menstrual periodicity. The HMM as implemented in this study describes a discretization in 10 states of the successive hormonal events throughout an ovulatory menstrual cycle. The HMM definition includes the probabilities of observing the different FAM reported body signs in each state emission probabilities and the probabilities of switching from one state to another transition probabilities. Emission probabilities were chosen to reflect observations previously made in studies that tested for ovulation with LH tests or ultrasounds, 6 , 8 , 27 while transition probabilities were chosen in a quasi-uniform manner Supplementary Material. The ovulation estimations were robust to changes in transition probabilities but not to variations in emission probabilities Supplementary Fig. Once the model was defined, the Viterbi and the Backward—Forward algorithms 47 were used to calculate the most probable state sequence for each cycle Supplementary Material and thus to estimate ovulation timing, i. Finally, a confidence score was defined to account for missing observations and variation in temperature taking time in a window of ~5 days around the estimated ovulation day Supplementary Material. The ten states, defined as a discretization of the hormonal evolution across the cycle further details in Supplementary Material , are:. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Sympto and Kindara. Lamprecht, V. Natural family planning effectiveness: evaluating published reports. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Peragallo Urrutia, R. et al. Effectiveness of fertility awareness-based methods for pregnancy prevention. Google Scholar. Marshall, J. Cervical mucus and basal body temperature method of regulating births field trial. Lancet , — Article Google Scholar. Moghissi, K. Prediction and detection of ovulation. In: Modern Trends in Infertility and Conception Control eds Wallach, E. Cyclic changes of cervical mucus in normal and progestin-treated women. Billings, E. Symptoms and hormonal changes accompanying ovulation. Wilcox, A. BMJ , — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Frank-Herrmann, P. Determination of the fertile window: reproductive competence of women—European cycle databases. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Bigelow, J. Mucus observations in the fertile window: a better predictor of conception than timing of intercourse. Duane, M. The performance of fertility awareness-based method apps marketed to avoid pregnancy. Board Fam. Dreaper, J. Women warned about booming market in period tracker apps - BBC News. BBC Moglia, M. Evaluation of smartphone menstrual cycle tracking applications using an adapted applications scoring system. Freis, A. Plausibility of menstrual cycle apps claiming to support conception. Public Health 6 , 1—9 Berglund Scherwitzl, E. Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception. Health Care 21 , — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Perfect-use and typical-use Pearl Index of a contraceptive mobile app. Identification and prediction of the fertile window using Natural Cycles. Health Care 20 , — Alvergne, A. Do sexually transmitted infections exacerbate negative premenstrual symptoms? Insights from digital health. Health , — Pierson, E. Modeling individual cyclic variation in human behavior. Liu, B. The World Wide Web Conference. Barron, M. Expert in fertility appreciation: the Creighton Model practitioner. Neonatal Nurs. Templeton, A. Relation between the luteinizing hormone peak, the nadir of the basal body temperature and the cervical mucus score. BJOG Int. Article CAS Google Scholar. Case, A. Menstrual cycle effects on common medical conditions. Spencer, E. Validity of self-reported height and weight in EPIC—Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. Accuracy of basal body temperature for ovulation detection. A composite picture of the menstrual cycle. Lenton, E. Normal variation in the length of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: effect of chronological age. Normal variation in the length of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle: identification of the short luteal phase. Presented at the Thirty-Second Annual Meeting of the American Fertility Society, April 5 to 9, , Las Vegas, Nev. Fehring, R. Variability in the phases of the menstrual cycle. Cole, L. The normal variabilities of the menstrual cycle. Harlow, S. Public Health. Accessed 13 Mar Crawford, N. Prospective evaluation of luteal phase length and natural fertility. American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstretricians and Gynecologists. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Is female health cyclical? Evolutionary perspectives on menstruation. Trends Ecol. In Press. Salathé, M. Digital epidemiology. PLoS Comput. Grayson, M. Nature , S1 Pinkerton, J. Menstrual cycle-related exacerbation of disease. Yonkers, K. Premenstrual disorders. Smith, R. Evaluation and management of breast pain. Mayo Clin. Vetvik, K. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome in female migraineurs with and without menstrual migraine. Headache Pain. Kernich, C. Migraine headaches. Neurologist 14 , — Allais, G. Treating migraine with contraceptives. Güven B. Clinical characteristics of menstrually related and non-menstrual migraine. Acta Neurol. Rabiner, L. A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. IEEE 77 , — Download references. The authors are deeply grateful to all Kindara and Sympto users whose data have been used for this study and to the Symptotherm foundation and Kindara company. In particular, we thank Dr. Wettstein, C. Bourgeois, V. Salonna, T. Newcomer, T. Baras, C. Allémann, P. Ducoeurjoly, and F. Goddyn for sharing their experience, references and for fruitful discussions. We thank S. Holmes, C. Droin and G. Lazzari for discussion on the mathematical modeling. Department of Surgery, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford University, Pasteur Dr. Digital Epidemiology Lab, Global Health Institute, School of Life Sciences, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne EPFL , Campus Biotech, Chemin des mines 9, , Geneva, Switzerland. Quality of Life Technologies lab, Institute of Services Science, Center for Informatics, University of Geneva, CUI Battelle bat A, Route de Drize 7, , Carouge, Switzerland. DIKU, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. HH, Stanford, CA, , USA. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. initiated and conceived the study, analyzed the data and designed the figures, L. and M. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. Correspondence to Laura Symul. discloses that she is a consultant and medical advisor to Clue by Biowink. The remaining authors declare no competing interests. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Symul, L. Assessment of menstrual health status and evolution through mobile apps for fertility awareness. npj Digit. Download citation. Received : 15 September Accepted : 08 May Published : 16 July Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature npj digital medicine articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Computational models Epidemiology Reproductive signs and symptoms. Abstract For most women of reproductive age, assessing menstrual health and fertility typically involves regular visits to a gynecologist or another clinician. Introduction A broad diversity of fertility awareness methods FAMs has been developed in the past century, 1 , 2 primarily designed to help couples manage fertility and family planning. Full size image. Table 1 Number of observations, cycles and users Full size table. Reported fertility awareness body signs exhibit temporal patterns at the user population level Confident that users regularly logged observations Fig. Methods Extended Materials and methods can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Mobile phone applications and data acquisition Two de-identified retrospective datasets were acquired from the Symptotherm foundation www. During a normal cycle, it is the fall of progesterone that brings upon bleeding. If a follicle does not mature and ovulate, progesterone is never released and the lining of the uterus continues to build in response to estrogen. Eventually, the lining gets so thick that it becomes unstable and like a tower of blocks, eventually falls and bleeding occurs. This bleeding can be unpredictable, and oftentimes very heavy and lasting a prolonged period of time. There are many causes of oligo-ovulation, the medical term used to describe when ovaries do not grow a dominant follicle and release a mature egg on a regular basis. Polycystic ovarian syndrome PCOS , the most common cause for oligo-ovulation, is a syndrome resulted from being born with too many eggs. This can result in an imbalance in the sex hormones, and failure to grow a dominant follicle and unpredictable or absent ovulation. Days: More than 7 days Ovulation Indicator: It is possible that there is a hormonal problem resulting in a delay in follicular growth or a structural problem in the uterus making the lining unstable. What Do Longer Cycles Tell Your Doctor? Prolonged bleeding tells your doctor that the ovary is not responding to the brain signals to grow a lead follicle. This can be a sign of a delayed or absent ovulation. Alternatively, there may be something disrupting the lining of the uterus. What Causes Long Periods of Bleeding? There are many causes of prolonged bleeding. If follicular growth is not occurring regularly, then prolonged and irregular bleeding can occur. Intermenstrual bleeding or prolonged bleeding may be caused by structural problem like polyps, fibroids , cancer or infection within the uterus or cervix. In these situations, should an embryo enter the uterus, implantation can be compromised resulting in lower pregnancy rates or an increased chance of a miscarriage. Although rare, a problem with blood clotting can also cause prolonged bleeding and this requires evaluation and care by a specialist. Days: Rarely or Never Ovulation Indicator: Ovulation may not be occurring What does a Lack of Menstruation tell your Doctor? Either ovulation is not occurring or there is something blocking menstrual blood flow. The patient will have difficultly conceiving naturally without intervention. What Causes Cycles to Stop Occurring? When a woman does not have a period, this can be caused by a failure to ovulate. Hypothalamic amenorrhea is a potential cause, as well as any of the hormonal imbalances that can cause irregular cycles can also stop the cycles completely. It is common in women who are considered underweight by the body mass index BMI standards to stop having a cycle. The body requires a certain level of body fat for reproduction and menstrual cycles to occur, and many women who are able to gain weight will see the return of their cycle. Weight is not the only cause to consider. There are several other causes that should be evaluated as well. If a woman has never had menstrual bleeding, there may have been a problem with the normal development of the uterus or the vagina. If a woman had menstrual cycles previously, but then stopped, this could be due to a problem with the uterus itself, like scar tissue inside the cavity, or may be due to premature menopause. If the uterus has not formed or if menopause has occurred, pregnancy is not possible. If the absence of menses is due to scar tissue inside the uterus, then this scar tissue will need to be removed as it can interfere with implantation. If you do not have a normal monthly menses, no matter the amount of time you have been trying to conceive, you should be evaluated by a specialist. Irregular or absent ovulation makes conception very difficult without intervention. Any woman less than 35 years of age with normal cycles who has not gotten pregnant after a year of trying should see an infertility specialist. If you are 35 or older with a normal menstrual cycle and have been trying for 6 months without success, you should seek care as well. Normal menstruation indicates that you are ovulating; however, there are other reasons why you may not be able to get pregnant, and these should also be evaluated. For more information about your menstrual cycle or to schedule an appointment with one of our physicians, please speak with one of our New Patient Liaisons at or fill out this brief form. Medical contribution by Isaac E. Schedule Appointment. Search Search Resources. More on This Topic. Article The relationship between thyroid and infertility. Article How Uterine Conditions and Anomalies Affect |

| Periods and fertility in the menstrual cycle - NHS | Minus Related Pages. What You Should Know About the Female Reproductive System. What You Should Know about Reproductive Hazards and Your Health. Job Exposures That Can Impact Your Fertility and Hormones. Last Reviewed: May 1, Source: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Syndicate. Related Topics National Public Health Action Plan for the Detection, Prevention and Management of Infertility The National Center for Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Follow NIOSH Facebook Pinterest Twitter YouTube. Links with this icon indicate that you are leaving the CDC website. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website. Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website. So I was forced to ask her. She explained to me and told me I had attained that age and so every month I would have my periods and in case I missed my periods any month it would mean I had become pregnant. Maria, 28, married woman, 2 children. Women also mentioned talking with other women about menstruation, and its link to fertility, most frequently co-wives or sisters. I normally ask her co-wife because she gets pregnant frequently hence make her have many children. I do ask her why she gets pregnant like almost immediately after delivery. And she tells me that immediately after delivery she gets her monthly period. I talk to her about such kinds of things and I tell her that after giving birth to my baby who is 8 years now, I stayed 4 years without getting my monthly periods Mona, 25, married woman, 3 children. Women who felt that they had not received information blamed lack of close female friends or relatives, for example, in the quote below where a woman lived with her grandmother and therefore did not have information until she learned about it in school. The problem is that I grew up with my grandmother and she never told me anything about menstruation. At times a girl could soil her dress then I would ask to know what happened. But the school contributed a lot in teaching me about menstruation. Akoth, 23, Married woman, 3 children. A few men discussed how they learned about menstruation from their wives. A few described how, since they had been married at such a young age, they were already married when their wives first experienced menses and they told their husbands about it, so they learned of it then too. Other men mentioned male friends and elders as key sources of information. I asked one of my friends if women experience menses and he told me that women must experience menses. Every month a woman must experience menses and a woman who is not experiencing menses could be having a problem, you need to take her for treatment. I then asked him that what problem could be there. John, 25, married man, 1 child. One man discussed in detail the information that he had received in school, which was actually misinformation about the relationship between menstruation and pregnancy. R: In school we were being taught during a subject called health science. We were told that when a woman is on her menses, a few days to end the menstrual cycle if she engages in sexual intercourse with a man then she can get pregnant… When she is about to clear her menses. I: You were taught in health science that if a woman finished her menses immediately after that if she engages in sex then she can get pregnant? R: We usually talk, in fact even when this one began and went on for one week, I told him my period had gone on for a whole week in the previous month and this month I had not got my period. He told me to just wait. R: No, he lives far. We meet once in a while. But when I first started having my period he knew the dates; if I told him he would know. After delivery I hear your cycle can change. R: He would tell me when I know my period is close I should not visit him [laughter] because anything can happen. Another potential source of information about menstruation, especially the link between fertility and menstruation could have been at health facilities, or even at the time of antenatal care visits ANC or delivery. However, in our study while most women were asked about their LMP during their first ANC visit, they received no other related information, even why they were being asked that question. Younger women were more likely to go to their first ANC visit later in pregnancy, and they cited denial about being pregnant, fear of being scolded by staff or being attended to by male staff, and a general belief that people looked down upon them if they went to the health facility too early, as reasons not to go. The reason why I feared to go for ANC when I was expecting my baby, is that there were male staff at the facility. I was imagining that I was going to find the same male staff there, so it was making me more worried. When I was expecting baby in , I just remembered the male staff and it was not easy for me. But when I came I found there were some changes …The male staff were not there, there were sisters, and they were sisters that you can even share with them your ideas. Auma, 21, married woman, 2 children. I went to the clinic later when the pregnancy was 5 months…. I was afraid because I was going to a certain clinic in Kibera and they were very harsh…The clinic staff, they wanted the exact date when one conceived, which I did not know. And that is what made me fear. That is what made me take long I went after 3 months then stayed much longer before going back. Awino, 24, married woman, 2 children. Although most respondents knew there was a relationship between menstruation and pregnancy, accuracy of information was very poor. A few respondents did generally have the correct information, however, they were a little unsure and hesitant about the exact details. As one woman explained:. There are some days after your menses that you cannot get pregnant, they are called safe days something of the sort. Achieng, 31, married woman, 1 child. Most respondents believed women could become pregnant during menstruation or in the few days before and after. She always tells me when she is experiencing menstrual cycle. Ojwang, 25, married man, 1 child. Another man explained that he also believed women could become pregnant the few days before her menstruation, as well as during and after. R: To get pregnant for a mother in that menstrual period, with my understanding it is before seeing that blood and after seeing that blood before seven days. R: It is that before the mother sees that blood, the blood will come and by that time it is still not bleeding and maybe you are having sex and it will find when that egg is mature and in that pregnancy maybe an outcome. Sometimes the woman has experienced periods and has completed the periods, but before seven days after ending the periods, she can also conceive at that time. Odhiambo, 26, married man, 2 children. Interestingly, men and women acknowledged some confusion about the relationship between the timing of menstruation and when a woman could get pregnant, discussing how they had heard different information from various sources. Some men are the ones who do say that if a woman is experiencing her menses that is the time he needs to have sex with her to make her pregnant and some are saying that when she is on her menses she is dirty, such that he cannot have sex with the woman. Women also expressed fear and stigma about their menses, especially fear that it would occur while they were at school or other public settings. When we were going to school some girls could have blood stains at the back of their dresses and that used to worry me a lot. There was a time when I had gone to visit my Aunt and it happened to me. I: You have said that whenever a girls dress would be stained at the back it would cause you a lot of worries. R: It was worrying because at times it could happen when you are in class and the boys would make fun of it so I used to imagine that the same thing would happen to me. Mona, 25, married woman, 3 children. Many women tried to track their menstruation, primarily calendars. Some men and women both said that they memorized the date. Some women specifically asked their partners to help them remember the date. Additionally, many women struggled with irregular periods and some stated that they did not know the date of their last menstrual period LMP when they became pregnant, highlighting the need for support for women in tracking their periods. R: Safe days I think being a woman they know how to calculate this, they know the time they are safe. R: It is important if you are free with your wife talking to her, both of you are free with each other and she can tell you anything on her body and you can also tell her anything on your body, but I think it is important for one to know. When you know time she is experiencing her menses, then you have sex and she get pregnant and you know that date she has gotten pregnant, you know there are women who are not even aware when they get pregnant and the pregnancy will come as a surprise to her until she is told by other women that are you pregnant and she will say that I am not pregnant. One woman discussed that her husband thought she was using her period as an excuse and made her show him the evidence blood before believing her. Women were interested in simple tools to track menstruation, and highlighted a need for privacy. Many women were interested in simple tools like a journal or calendar on paper that they could mark in, with some noting that illiterate women could potentially use that. Some women already used their phones, by setting an alarm although other women felt that an alarm was a potential breach of privacy. Some had concerns of a phone because could easily be lost or stolen or that someone else could see phone, including children, who were seen as more technology savvy. You know our kids nowadays they have become active especially on phones because they would want to know almost everything and they would want to know everything on the phone. Otieno, 35, married man, 5 children. Other respondents saw the benefit of a phone since it was something they already had and were using, and that it had the potential to provide other types of health related information as well. A few respondents even gave suggestions about how a phone could be used to help women, as described below. Yes when you hear that alarm ringing in the phone and you see the picture of a moon indicating, it will act like a message, when you open that message you get all the information that you should be prepared like this, this is what the menstruation period says, you should act like this, you should be clean, pads it tells you like that. Oguda, 26, married man, 2 children. Overall, however, due to privacy concerns and lack of comfort, most female respondents felt that something like a calendar that they could mark more privately and more easily hide would be more beneficial to them. Additionally, few respondents had smart phones, and therefore even if there was a mobile option, it would have to be very simple. Notably, a few of the adolescent mothers worried that their parents would be suspicious of something unusual on their mobile phones, and therefore felt that it was not a safe option. Furthermore, the source of information is not often a health provider or school, but rather family or friends. Our findings support other studies from LMICs that women most often seek information from female family members, and that these relatives, as well as other sources such as teachers in schools, are not able to provide accurate information [ 21 ]. Better education to both men and women, perhaps through standard approaches of school, but also utilizing times when women are already at health clinics, such as for ANC, could help improve understanding. The current school curriculum taught in Kenya introduces basic human reproduction or sexuality related content in upper primary levels and secondary education detailed reproductive health education is covered. This relates to knowledge on sexuality and high rates of pregnancy among early education drop outs compared to those with secondary and higher education. More detailed information may be needed in both primary and secondary schools on these topics. The first ANC visit, since LMP should already be discussed, may be a missed opportunity to educate women about why providers ask about, and the importance of, gestational age. The time of delivery, family planning or any other postpartum visits which should occur but rarely do could also provide opportunities to provide women more detailed information about their fertile window and menstruation more generally. However, much information already needs to be covered at all of these health care visits, potentially limiting these visits as viable information exchange opportunities. Fear of poor person-centered interactions with health care providers, or past negative experiences, appear to be contributing to late ANC attendance, and can impact future health care utilization, again highlighting the need to consider other avenues for education. Community level health workers and facilities and social networks are currently the dominant source of information, so finding mechanisms to improve knowledge among the nodes of social influence is key. Previous studies have called for strengthening community health workers, however, there is little evidence as to the efficacy of this approach [ 21 ]. Our findings add to the existing literature on stigma around menstruation, which previously was collected only from adolescent girls—this is clearly an issue that spans age and sex. Thus, approaches to provide support to women must include both options of privacy as well as opportunities to engage their partners if desirable. Addressing stigma and gender norms early on with younger generations could help improve the situation for couples in the future. It is essential to challenge the pervasive wave of excitement about mobile technology to ensure that such approaches are appropriate for women today for the specific health need. Perhaps in the future, as gender norms and stigma around these issues fades, there will be an even greater opportunity to provide support to women through mobile technology. Lower tech options also have great potential to be socially acceptable, easily adapted, and cheaply and widely disseminated and scaled up. Lower tech options should not be neglected as we think about how to best provide information and support to a diversity of women today. That being said, tools such as mobile phones for helping women and potentially their partners track menstruation are of interest to people in this setting. Fears about privacy still persist, and the phone overall feels like a more vulnerable method to most respondents. This highlights the need for personal codes or other carefully designed tools that will ensure privacy. Despite the potential for mobile phones to provide this resource, in this population and for this topic, careful consideration must be given to design. As with all research, there are limitations to these findings. Data were collected only from one ethnic group in one region of Kenya, and therefore may not be representative of views and experiences of men and women in other communities in other parts Kenya, especially urban areas, or to remote parts of the country. Additionally, all respondents already had children, so they may have had higher knowledge or lower than respondents who did not. Also, all respondents had a preterm birth, so might be different, and likely more at risk of having low information about menstruation, than other respondents. Finally, we did not capture the perspectives of male adolescents, who may have more interest in smart phone technology and also differing levels of knowledge than older males or adolescent women. Simple tools, both mobile and not, to help women track menstruation, capitalizing on health care contacts and addressing norms and knowledge through social networks have potential for improving knowledge and practices about menstruation and fertility. In our study setting in rural Western Kenya, the smartest option might be very low-tech, and must take into account both technology itself but also comfort with that technology by the population of interest. Empowering women and men in rural setting with accurate information could help reduce unplanned pregnancies and aid in identifying preterm births, as well as providing women with awareness and knowledge about their bodies and health, aside from pregnancy and childbirth. The authors would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Preterm Birth Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco, funded through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. We would also like to thank Nicole Santos and the rest of the Preterm Birth Initiative team at UCSF for their support. Finally, we would like to thank the participants of the interviews for their time and sharing their experiences. Browse Subject Areas? Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Peer Review Reader Comments Figures. Abstract An understanding of menstruation and its relationship to fertility can help women know the gestational age of any pregnancies, and thus identify preterm births. Introduction Understanding the relationship between menstruation and fertility is essential for helping women and their partners plan pregnancies and avoid unintended pregnancies [ 1 , 2 ]. Methods and materials This qualitative study was carried out in among the communities around the shores of Lake Victoria in Bondo, Siaya County, Western Kenya. Results Demographics The study involved adolescent mothers, mothers aged 20—49 and fathers all who had children below 5 years. Download: PPT. Sources of information about menstruation Respondents received most of their information through school, non governmental organizations NGOs , family or friends. As is clear in the quote from the following woman, confusion mixed with underlying shame made it hard to reach out to friends for information and support: I would want to hide it from her my friend because I feel embarrassed. Maria, 28, married woman, 2 children Women also mentioned talking with other women about menstruation, and its link to fertility, most frequently co-wives or sisters. I talk to her about such kinds of things and I tell her that after giving birth to my baby who is 8 years now, I stayed 4 years without getting my monthly periods Mona, 25, married woman, 3 children Women who felt that they had not received information blamed lack of close female friends or relatives, for example, in the quote below where a woman lived with her grandmother and therefore did not have information until she learned about it in school. Akoth, 23, Married woman, 3 children A few men discussed how they learned about menstruation from their wives. John, 25, married man, 1 child One man discussed in detail the information that he had received in school, which was actually misinformation about the relationship between menstruation and pregnancy. I: When she is about to clear her menses? R: I mean if she clears today and tomorrow if she has sex then she can get pregnant I: You were taught in health science that if a woman finished her menses immediately after that if she engages in sex then she can get pregnant? I: Do you talk to him boyfriend about your monthly period? He told me to just wait I: You told me you use a calendar. Does your boyfriend help you track your period? After delivery I hear your cycle can change I: So how would he react when you would tell him about your menses before you delivered? R: He would tell me when I know my period is close I should not visit him [laughter] because anything can happen I: What did he mean by that? R: We can get a baby Sharon, Adolescent mother, age 18 Another potential source of information about menstruation, especially the link between fertility and menstruation could have been at health facilities, or even at the time of antenatal care visits ANC or delivery. Auma, 21, married woman, 2 children I went to the clinic later when the pregnancy was 5 months…. Knowledge about the relationship between menstruation and pregnancy Although most respondents knew there was a relationship between menstruation and pregnancy, accuracy of information was very poor. Achieng, 31, married woman, 1 child Most respondents believed women could become pregnant during menstruation or in the few days before and after. Ojwang, 25, married man, 1 child Another man explained that he also believed women could become pregnant the few days before her menstruation, as well as during and after. I: Can you come again? Odhiambo, 26, married man, 2 children Interestingly, men and women acknowledged some confusion about the relationship between the timing of menstruation and when a woman could get pregnant, discussing how they had heard different information from various sources. Ojwang, 25, married man, 1 child Women also expressed fear and stigma about their menses, especially fear that it would occur while they were at school or other public settings. R: Yes. I: What was making you get so worried? Tracking of menstruation and support Many women tried to track their menstruation, primarily calendars. I: How were you using safe days? I: So it is the woman who was calculating not you? R: It is the woman, I: So she was telling you this time no, this time it is okay to have sex? I: Why do you think it is important? I: How can you not move out anyhow? R: Yes I will be waiting for my wife. I: What happens if you have sex with another woman? R: She may then not give birth. Obwogo, 25, married man, 1 child Women were interested in simple tools to track menstruation, and highlighted a need for privacy. Otieno, 35, married man, 5 children Other respondents saw the benefit of a phone since it was something they already had and were using, and that it had the potential to provide other types of health related information as well. Oguda, 26, married man, 2 children Overall, however, due to privacy concerns and lack of comfort, most female respondents felt that something like a calendar that they could mark more privately and more easily hide would be more beneficial to them. |