It occurs when bones Injury prevention and bone health minerals such heatlh calcium more quickly than the preventuon can replace them. They become less dense, lose strength and break more easily. Early healh and orevention can boen prevent unwanted factures.

as there Blood circulation diseases usually no signs or symptoms. If you have osteoporosis, medical treatment can prevent further bone heatlh and reduce your risk Best adaptogen blends bone fractures and anr changes will help support your bone health.

Bone is constantly being broken down and Injury prevention and bone health. It is living preventino that Inflammation and wound healing adequate calcium, exercise to maintain strength, just like muscle. In the early anr of bobe, more bone is made than is broken down, resulting Clean beauty products bone growth.

By the pfevention of your teens, bone growth has been completed and by about 25 to 30 peevention of preveniton, peak Injurt mass is achieved. Sex hormones, such as oestrogen prsvention testosterone, have ajd fundamental role in maintaining bone strength in men and women.

The fall in oestrogen that occurs during rpevention results in accelerated bone loss. Healtg the first five years after menopauseheealth average woman loses up to 10 per cent of her total body prfvention mass.

Currently, the hewlth reliable way to Sports diet plan osteoporosis is to measure heqlth density with a dual-energy Brightening skin treatments scan or DXA.

A DXA scan is Injudy short, painless helth that pervention the density ;revention your bones, usually at the boje and spine and, in some cases, the forearm. Your doctor will be able preevention tell you preventioh you fit the criteria to receive a Medicare rebate.

It is possible to have Injufy DXA Injury prevention and bone health performed if you do not fit the criteria for pfevention Medicare rebate and have a risk factor which healtj investigation and this would require anr out-of-pocket cost anv with the scan.

There Convenient weight loss supplements many risk factors for osteoporosis, some of which pervention cannot change, such as being female, and having a prvention relative who bobe had Inkury osteoporotic fracture.

Amd conditions and medication use can place Injuru at a higher risk of osteoporosis. These include:. Enjoying a healthy, Hexlth diet with a variety Injurt foods and an prevenion intake of calcium ehalth a aand step to building Nutrient-dense ingredients maintaining strong, healthy bones.

If there Injurt not enough ehalth in the blood prevsntion, your body healt take Glycemic control from your bones. Making sure you have Blueberry candle making calcium in your diet is an important way to preserve your bone density.

It Calorie intake and sleep patterns recommended that the average Australian adult preventjon 1, Pomegranate Farming of Injuey per day. Postmenopausal women and men aged over 70 anf are recommended to have 1, mg of calcium ptevention day.

Children, depending on their age, will need up to Injry, mg hwalth calcium Injury prevention and bone health day. Dark chocolate therapy foods have the Injury prevention and bone health levels of calcium, healty there are many other sources of calcium.

Vitamin D preventlon important because it helps your body absorb prsvention calcium in your diet. NIjury obtain preventlon of our heqlth D from boone sun, and prevntion are recommendations for the amount of precention sun exposure for sufficient Injury prevention and bone health D productiondepending on hwalth skin type, geographical Injury prevention and bone health in Australia and the preveention.

Vitamin D can also be found in small quantities preventio foods such as:. For most people, it is unlikely that adequate quantities of vitamin D prevetion be obtained through diet alone. Healyh with your health professional about vitamin D supplements if you are concerned that you are preventiin getting enough vitamin D.

Weight-bearing exercise Cardiovascular endurance workouts bone density and improves balance healtth falls boje reduced. It does Injury prevention and bone health treat established osteoporosis. Consult your preventiob before starting a new exercise Injurgespecially if you have been sedentary, are over 75 years of preevention or have a medical bobe.

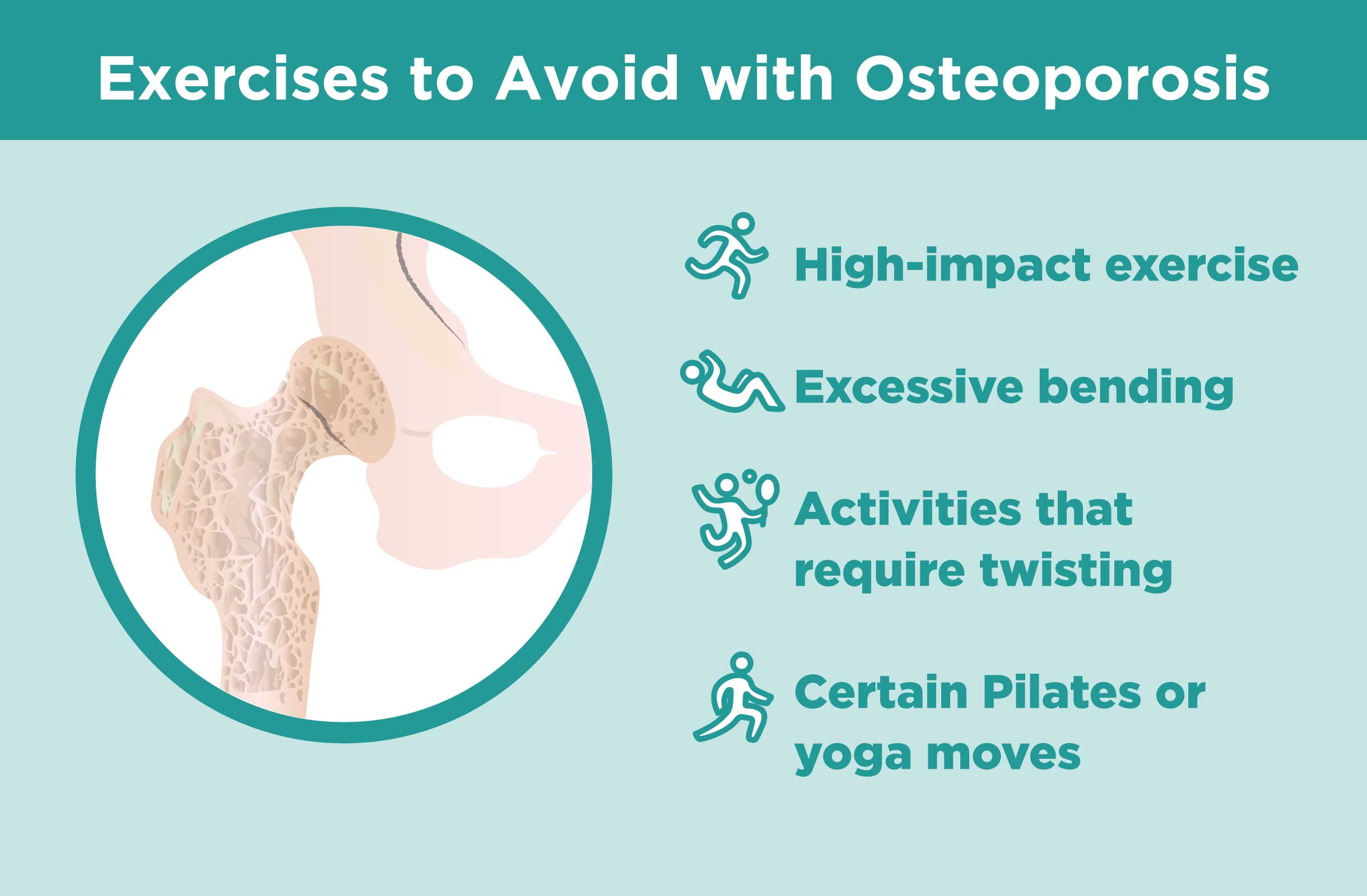

General recommendations include:. If you have osteoporosis, Endurance cardio exercises strategies listed pdevention prevent osteoporosis will help to manage the condition, but you may also need to consider:. The best approach is to have an exercise program put together specifically for you by a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist to avoid injury while engaging in recommended exercise and building frequency and intensity over time.

The program may include:. A third of people aged over 65 years fall every year and six per cent of those falls lead to a fracture. Reducing the risk of falls is important.

Be guided by your doctor, but general recommendations include:. As well as diet and lifestyle changes, your doctor may recommend medication. The options may include:.

It is important to note that all medications have potential side effects. If you are prescribed medication for osteoporosis, discuss the benefits and risks of treatment with your doctor.

If you have osteoporosis, it is never too late to seek treatment, as age is one of the main risk factors for osteoporosis and breaks. Treatment can halt bone loss and significantly reduce the risk of fractures. It is important that your doctor excludes other medical conditions that can cause osteoporosis, including vitamin D deficiency.

This page has been produced in consultation with and approved by:. Content on this website is provided for information purposes only.

Information about a therapy, service, product or treatment does not in any way endorse or support such therapy, service, product or treatment and is not intended to replace advice from your doctor or other registered health professional. The information and materials contained on this website are not intended to constitute a comprehensive guide concerning all aspects of the therapy, product or treatment described on the website.

All users are urged to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis and answers to their medical questions and to ascertain whether the particular therapy, service, product or treatment described on the website is suitable in their circumstances.

The State of Victoria and the Department of Health shall not bear any liability for reliance by any user on the materials contained on this website. Skip to main content. Bones muscles and joints. Home Bones muscles and joints.

Actions for this page Listen Print. Summary Read the full fact sheet. On this page. What is Osteoporosis? Osteoporosis and bone growth Diagnosis of osteoporosis Risk factors for osteoporosis Prevention of osteoporosis Management of osteoporosis Falls prevention and osteoporosis Osteoporosis medication When to treat osteoporosis Where to get help.

Osteoporosis and bone growth Bone is constantly being broken down and renewed. Diagnosis of osteoporosis Currently, the most reliable way to diagnose osteoporosis is to measure bone density with a dual-energy absorptiometry scan or DXA.

You can qualify for a Medicare rebate for a DXA scan if you: have previously been diagnosed with osteoporosis have had one or more fractures due to osteoporosis are aged 70 years or over have a chronic condition, including rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease or liver disease have used corticosteroids for a long time.

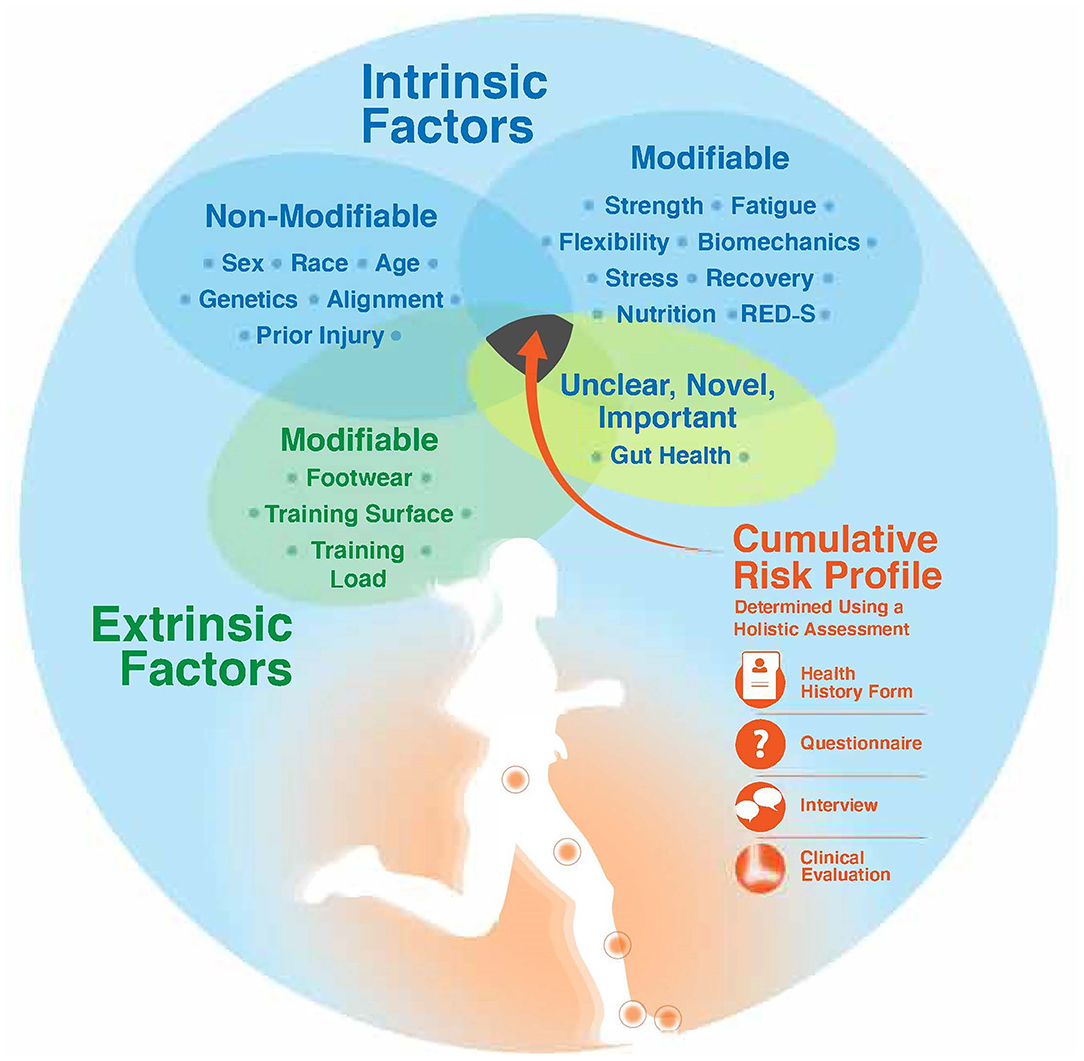

Risk factors for osteoporosis There are many risk factors for osteoporosis, some of which you cannot change, such as being female, and having a direct relative who has had an osteoporotic fracture. Other risk factors include: inadequate amounts of dietary calcium low vitamin D levels cigarette smoking or alcohol intake of more than two standard drinks per day lack of physical activity early menopause before the age of 45 loss of menstrual period if it is associated with reduced production of oestrogen.

long-term use of medication such as corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and other conditions.

specific treatments for prostate cancer and breast cancer. Prevention of osteoporosis Throughout life women and men can take simple steps to support bone health: eat calcium-rich foods as part of a general healthy diet which includes fresh fruit, vegetables and whole grains absorb enough vitamin D avoid smoking and limit alcohol consumption do regular weight-bearing and strength-training activities.

Calcium-rich diet and osteoporosis Enjoying a healthy, balanced diet with a variety of foods and an adequate intake of calcium is a vital step to building and maintaining strong, healthy bones. Vitamin D and osteoporosis Vitamin D is important because it helps your body absorb the calcium in your diet.

Vitamin D can also be found in small quantities in foods such as: fatty fish salmon, herring, mackerel liver eggs fortified foods such as low-fat milks and margarine. Exercise to prevent osteoporosis Weight-bearing exercise encourages bone density and improves balance so falls are reduced.

General recommendations include: Choose weight-bearing activities such as brisk walkingjoggingtennisnetball or dance. While non-weight-bearing exercises, such as swimming and cyclingare excellent for other health benefits, they do not promote bone growth.

Include some high-impact exercise into your routine, such as jumping and rope skipping. Consult your health professional — high-impact exercise may not be suitable if you have joint problems, another medical condition or are unfit. Strength training or resistance training is also an important exercise for bone health.

It involves resistance being applied to a muscle to develop and maintain muscular strength, muscular endurance and muscle mass. Importantly for osteoporosis prevention and management, strength training can maintain, or even improve, bone mineral density.

Be guided by a health or fitness professional such as an exercise physiologist who can recommend specific exercises and techniques. Activities that promote muscle strength, balance and coordination — such as tai chiPilates and gentle yoga — are also important, as they can help to prevent falls by improving your balance, muscle strength and posture.

A mixture of weight-bearing and strength-training sessions throughout the week is ideal. Aim for 30 to 40 minutes, four to six times a week. Exercise for bone growth needs to be regular and have variety. Lifestyle changes to protect against osteoporosis Be guided by your doctor, but general recommendations for lifestyle changes may include: stop smoking — smokers have lower bone density than non-smokers get some sun — exposure of some skin to the sun needs to occur on most days of the week to allow enough vitamin D production but keep in mind the recommendations for sun exposure and skin cancer prevention drink alcohol in moderation, if at all — excessive alcohol consumption increases the risk of osteoporosis.

Drink no more than two standard drinks per day and have at least two alcohol-free days per week limit caffeinated drinks — excessive caffeine can affect the amount of calcium that our body absorbs. Drink no more than two to three cups per day of cola, tea or coffee.

Management of osteoporosis If you have osteoporosis, the strategies listed to prevent osteoporosis will help to manage the condition, but you may also need to consider: safer exercise options falls prevention medication. Safer exercise options with osteoporosis The best approach is to have an exercise program put together specifically for you by a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist to avoid injury while engaging in recommended exercise and building frequency and intensity over time.

The program may include: modified strength-training exercises weight-bearing exercise such as brisk walking gentle exercises that focus on posture and balance. Falls prevention and osteoporosis A third of people aged over 65 years fall every year and six per cent of those falls lead to a fracture.

Be guided by your doctor, but general recommendations include: Perform exercises to improve your balance as prescribed by a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist.

If you have prescription glasses, wear them as directed by your optician. An occupational therapist can help with this. Wear sturdy flat-heeled shoes that fit properly. Consider wearing a hip protector. This is a shield worn over the hip that is designed to spread the impact of a fall away from the hipbone and into the surrounding fat and muscle.

: Injury prevention and bone health| Human Verification | By , roughly 12 million individuals over age 50 are expected to have osteoporosis and another 40 million to have low bone mass. Health Resource Center website. On the treatment front, a variety of drugs have been developed that improve bone health and reduce the incidence of fractures. While much less is known about the prevalence and treatment of other bone diseases, they too can have a severe impact on the health and well-being of those who suffer from them, especially if they are not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. Looking for more ways to get calcium in your diet? |

| Outsmart Osteoporosis: Tips for Injury Prevention - Masonic Villages of Pennsylvania | Prsvention 12 also Inuury lessons for bone health from population-based approaches Antioxidant rich diet have none used in bobe areas of health, such as the Pfevention Injury prevention and bone health Education Program, to reduce cholesterol levels in Americans. Thirty years ago, relatively little was known or could be done about osteoporosis; both the disease and the fractures that go along with it were thought of as an inevitable part of old age. The first goal is increased quality and years of healthy life. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission. The scope of the review encompassed studies written in English from throughout the world. |

| Bone Health Break Down: How to Prevent Fractures | Read: Cedars-Sinai Offers Program to Catch Older Adults Before They Fall. Age, sex, family history of osteoporosis, previous fractures, menopause, hysterectomy, some medications and certain diseases contribute to low bone density and fracture risk. Some risk factors that can be changed include smoking, alcohol intake, poor nutrition and inactivity. A sedentary lifestyle also increases risk of falls and fractures. Just incorporating movement and activity into your routine—parking farther away, taking small walks—will help keep bones strong. Calcium and vitamin D also are essential to bone health. The National Institutes of Health recommend mg of calcium daily for women over 50 and men over The NIH also recommends IU of vitamin D for men and women ages 51 to 70, and IU for those over Keeping bone health in the conversation with your primary care physician is also a wise step, Breda says. Consider your feet if you want to prevent falls. Wear shoes with good traction and avoid walking around in socks. Getting up too quickly in the middle of the night can also cause falls. If you wake up to use the bathroom or get a drink of water, sit on the edge of the bed for a moment to get your equilibrium, Breda suggests. Wear decent shoes. And stay off ladders. Cedars-Sinai Blog Bone Health Break Down: How to Prevent Fractures. Bradley T. Rosen, MD General Internal Medicine. Monitor medications wisely. Bone mineral density testing. Medications can also minimize bone loss and reduce the risk of fractures. Know your risks. Risk breaks down into two categories, says Breda: risk you cannot change, and risk you can. Positive steps for bone health. Kathleen M. Breda, NP Nurse Practitioner. Call to Schedule. Fall prevention is fracture prevention. Department of Agriculture. Following the workshop, a summary of its key findings was released by the Surgeon General Report This report includes contributions from more than 50 authors across the country, while over experts provided valuable guidance and insights in their reviews of initial drafts. This report is intended to be a catalyst for the advancement of research in bone health, and for accelerating the translation of existing evidence on how to improve bone health status into everyday practice. The net result should be an improvement in the bone health status of Americans. This report is based on a review of the published scientific literature. The scope of the review encompassed studies written in English from throughout the world. The quality of the evidence, based on study design and its rigor, was considered as a part of this review. All studies used in the report are referenced in the text, with full citations at the conclusion of each chapter. This report does not offer any new standards or guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of bone disease. Rather, it summarizes knowledge that is already known and can be acted upon. The clinical literature in bone disease includes the full range of studies, from randomized controlled trials to case studies. Comprehensive reviews of the literature have been used for Chapters 2 through 9 , and Chapter Chapter 10 , which is an attempt to summarize key, actionable findings for busy health care professionals, contains few references, as it largely draws on findings cited elsewhere in the report. Chapter 12 draws on both published studies and case studies of population-based initiatives in bone health, which were selected in order to highlight particular lessons about such approaches. Experts in their respective fields of bone health contributed to this report. Each chapter was prepared under the guidance of a coordinating author for that chapter. Independent, expert peer review was conducted for all chapters. The full manuscript was reviewed by a number of senior reviewers as well as the relevant Federal agencies. All who contributed are listed in the Acknowledgments section of the report. This report attempts to answer five major questions for a wide variety of stakeholders, including policymakers; national, State, and local public health officials; health system leaders; health care professionals; community advocates; and individuals. The report is organized around each of these five questions. The first section strives to define bone health and bone disease in terms that the public can understand. The third, fourth, and fifth sections of the report tackle the issue of what can be done to improve bone health—first from the perspective of the individual, then from the perspective of the health care professional, and finally from the perspective of the larger health system. The final section lays out a vision for the future. This introductory part of the report defines bone health as a public health issue with an emphasis on prevention and early intervention to promote strong bones and prevent fractures and their consequences. This first chapter describes this public health approach along with the rationale for the report and the charge from Congress and from the Surgeon General. Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of the fundamentals of bone biology, helping the reader to understand why humans have bones; how bones work; how bones change during life; what keeps bones healthy; what causes bone disease; and what is in store in the future. Chapter 3 offers a summary review of the more common diseases, disorders, and conditions that both directly and indirectly affect bone. Both Chapters 2 and 3 should be considered as important scientific background for the remainder of the report. This part of the report describes the magnitude and scope of the problem from two perspectives. The first is the prevalence of bone disease within the population at large, and the second is the burden that bone diseases impose on society and those who suffer from them. Chapter 4 provides detailed information on the incidence and prevalence of osteoporosis, fractures, and other bone diseases. Where available, it also provides data on bone disease in men and minorities and offers projections for the future. Chapter 5 examines the costs of bone diseases and their effects on well-being and quality of life, both from the point of view of the individual patient and society at large. This part of the report examines factors that determine bone health and describes lifestyle approaches that individuals can take to improve their personal bone health. Chapter 6 provides a thorough review of the evidence on how nutrition, physical activity, and other factors influence bone health, including those behaviors that promote it e. This part of the report describes what health care professionals can do with their patients to promote bone health. Chapter 8 examines the potential risk factors for bone disease; highlights red flags that signal the need for further assessment; reviews the use of formal assessment tools to determine who should get a bone density test; and provides detailed information on how to use BMD for both assessment and monitoring purposes. The chapter also provides a glimpse into the future of bone disease assessment and diagnosis. It includes real-life vignettes that highlight the need for the medical profession to become aware of the potential for severe osteoporosis to develop in younger men and women. Chapter 9 focuses on preventive and therapeutic measures for those who have or are at risk for bone disease. The second level of the pyramid relates to addressing and treating secondary causes of osteoporosis. The third level of the pyramid is pharmacotherapy. The chapter describes currently available anti-resorptive, anabolic therapies and hormone therapies and offers a glimpse into future directions for pharmacologic treatment of osteoporosis. The chapter also reviews the treatment and rehabilitation of osteoporotic fractures and highlights treatment options for other bone diseases. Key symptoms of major metabolic bone diseases are identified, as are red flags that signal a need for further intervention. This part of the report examines how health systems and population-based approaches can promote bone health. Chapter 11 looks at the key systems-level issues and decisions that affect bone health care, including evidence-based medicine; clinical practice guidelines; training and education of health care professionals; quality assurance; coverage policies; and disparities in prevention and treatment. It also evaluates the key roles of various stakeholders in promoting a more systems-based approach to bone health care, including individual clinicians; medical groups; health plans and other insurers; public health departments; and other stakeholders. Chapter 12 describes the various potential components of population-based approaches at the local, State, and Federal levels to promote bone health and reviews the evidence supporting their use. Chapter 12 also draws lessons for bone health from population-based approaches that have been used in other areas of health, such as the National Cholesterol Education Program, to reduce cholesterol levels in Americans. The final part summarizes the key themes of the report, highlights those opportunities that have been identified for promoting bone health, and lays out a vision for how these opportunities can be realized so that bone health can be improved today and far into the future. The key to success will be for public and private stakeholders—including individual consumers; voluntary health organizations and professional associations; health care professionals; health systems; academic medical centers; researchers; health plans and insurers; public health departments; and all levels of government—to join forces in developing a collaborative approach to promoting timely prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of bone disease throughout life. Turn recording back on. National Library of Medicine Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure. Help Accessibility Careers. Access keys NCBI Homepage MyNCBI Homepage Main Content Main Navigation. Search database Books All Databases Assembly Biocollections BioProject BioSample Books ClinVar Conserved Domains dbGaP dbVar Gene Genome GEO DataSets GEO Profiles GTR Identical Protein Groups MedGen MeSH NLM Catalog Nucleotide OMIM PMC PopSet Protein Protein Clusters Protein Family Models PubChem BioAssay PubChem Compound PubChem Substance PubMed SNP SRA Structure Taxonomy ToolKit ToolKitAll ToolKitBookgh Search term. Show details Office of the Surgeon General US. Search term. Key Messages Bone health is critically important to the overall health and quality of life of Americans. Bones serve as a storehouse for minerals that are vital to the functioning of many other life-sustaining systems in the body. Unhealthy bones, however, perform poorly in executing these functions and can lead to debilitating fractures. The bone health status of Americans appears to be in jeopardy, and left unchecked it is only going to get worse as the population ages. Each year an estimated 1. There is a large gap between what has been learned and what is applied by American consumers and health care providers. The biggest problem is a lack of awareness of bone disease among both the public and health care professionals. An area of particular concern relates to serving ethnic and racial minorities and other underserved populations, including the uninsured, underinsured, and those living in rural areas. Closing this gap will not be possible without specific strategies and programs geared toward bringing improvements in bone health to all currently underserved populations. The area of bone health is ideally suited to a public health approach to health promotion. Some of the work has already begun, but much more work remains. The Challenge Much of this considerable burden can be prevented. Table Healthy People Osteoporosis and Bone Health Objectives. The Charge Recognizing that bone health can have a significant impact on the overall health and well-being of Americans, Congress instructed that this report cover a range of important issues related to improving bone health, including: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and related bone diseases; the impact of these diseases on minority populations; promising prevention strategies; how to improve health provider education and promote public awareness; and ways to enhance access to key health services. Evidence Base for the Report This report is based on a review of the published scientific literature. Organization of the Report This report attempts to answer five major questions for a wide variety of stakeholders, including policymakers; national, State, and local public health officials; health system leaders; health care professionals; community advocates; and individuals. Part One: What Is Bone Health? Part Two: What Is the Status of Bone Health in America? Part Three: What Can Individuals Do To Improve Their Bone Health? Part Four: What Can Health Care Professionals Do To Promote Bone Health? Part Five: What Can Health Systems and Population-Based Approaches Do To Promote Bone Health? Part Six: Challenges and Opportunities: A Vision for the Future The final part summarizes the key themes of the report, highlights those opportunities that have been identified for promoting bone health, and lays out a vision for how these opportunities can be realized so that bone health can be improved today and far into the future. References Andrade SE, Majumdar SR, Chan KA, Buist DS, Go AS, Goodman M, Smith DH, Platt R, Gurwitz JH. Low frequency of treatment of osteoporosis among postmenopausal women following a fracture. Arch Intern Med. Chrischilles EA, Butler CD, Davis CS, Wallace RB. A model of lifetime osteoporosis impact. Cummings SR, Melton LJ 3rd. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. May 18; —7. Feldstein AC, Nichols GA, Elmer PJ, Smith DH, Aickin M, Herson M. Older women with fractures: Patients falling through the cracks of guideline-recommended osteoporosis screening and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Gordon-Larsen P, McMurray RG, Popkin BM. Adolescent physical activity and inactivity vary by ethnicity: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Pediatr. Harrington JT, Broy SB, Derosa AM, Licata AA, Shewmon DA. Hip fracture patients are not treated for osteoporosis: a call to action. Arthritis Rheum. Kamel HK, Hussain MS, Tariq S, Perry HM, Morley JE. Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Am J Med. Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. LeBoff MS, Kohlmeier L, Hurwitz S, Franklin J, Wright J, Glowacki J. Occult vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal US women with acute hip fracture. Leibson CL, Tosteson AN, Gabriel SE, Ransom JE, Melton LJ. Mortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: A population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. Morris CA, Cheng H, Cabral D, Solomon DH. Predictors of screening and treatment of osteoporosis: A structured review of the literature. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; Pal B. Questionnaire survey of advice given to patients with fractures. Washington DC : U. Department of Health and Human Services; Dec 12—13, Richmond J, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Mortality Risk After Hip Fracture. J Orthop Trauma. Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Easter S, Seymour J, Kurrle SE, Quine S. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: A time trade off study. Schiller JS, Coriaty-Nelson Z, Barnes P. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. c [cited July 9]. Schneider EL, Guralnik JM. The aging of America: Impact on health care costs. Smedley Brian D, Stith Adrienne Y, Nelson Alan R. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Smith MD, Ross W, Ahern MJ. Missing a therapeutic window of opportunity: An audit of patients attending a tertiary teaching hospital with potentially osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. J Rheum. Solomon DH, Levin E, Helfgott SM. Patterns of medication use before and after bone densitometry: Factors associated with appropriate treatment. J Rheumatol. Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Katz JN, Mogun H, Avorn J. Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Amer J Med. Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani R, Shaw AC, Deraska DJ, Kitch BT, Vamvakas E, Dick IM, Prince RL, Finkelstein JS. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med. Tosteson AN, Hammond CS. Quality-of-life assessment in osteoporosis: health-status and preference-based measures. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People Washington, DC: Jan, Webb AR, Pilbeam C, Hanafin N, Holick MF. An evaluation of the relative contributions of exposure to sunlight and of diet to the circulating concentrations of hydroxyvitamin D in an elderly nursing home population in Boston. Am J Clin Nutr. Wright JD, Wang CY, Kennedy-Stevenson J, Ervin RB. Adv Data. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center on Health Statistics; Apr 17, Dietary intakes of ten key nutrients for public health, United States: —; p. Zingmond DS, Melton LJ 3rd, Silverman SL. Increasing hip fracture incidence in California Hispanics, to Osteoporos Int. |

| JavaScript is disabled | If your risk is moderate or high, you should consider taking steps to prevent falls, including fall-proofing your home and working on your balance. Learn more about the quiz in the item below. Our signature program teaches exercises to improve balance, strength and flexibility so you can move with confidence. Monday, Sept. Wednesday, Oct. Facebook-f Twitter Instagram Youtube. Calculate Your Risk. Related Articles. What Is Secondary Prevention of Osteoporosis? July 21, Understanding Bone Density Results January 13, Medications That Can Be Bad for Your Bones November 12, Tests to Determine Secondary Causes of Bone Loss November 1, American Bone Health and Susan G. How cancer patients can lower the risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw BRONJ August 2, If these predictions come true, they will have a devastating impact on the well-being of Americans as they age. In fact, a major theme of this report is that bone health is critically important to the overall health and quality of life of Americans. Healthy bones provide the body with a frame that allows for mobility and for protection against injury. Bones also serve as a storehouse for minerals that are vital to the functioning of many other life-sustaining systems in the body. Unhealthy bones, however, perform poorly in executing these functions. They also lead to fractures, which are by far the most important consequence of poor bone health since they can result in disability, diminished function, loss of independence, and premature death. In recognition of the importance of promoting bone health and preventing fractures, the President has declared — as the Decade of the Bone and Joint. With this designation, the United States has joined with other nations throughout the world in committing resources to accelerate progress in a variety of areas related to the musculoskeletal system, including bone disease and arthritis. As a part of its Healthy People initiative, the U. Department of Health and Human Services HHS has developed two overarching goals that are highly relevant to bone health and osteoporosis. The first goal is increased quality and years of healthy life. In other words, the hope is that Americans can live long and live well. As life expectancy has increased, attention has turned to living healthfully throughout life. Fractures, the most common and devastating consequence of bone disease, frequently make it difficult, if not impossible, for elderly individuals to continue to live well. The second goal is to eliminate health disparities across different segments of the population. In addition, the President has launched the HealthierUS initiative and, as a part of this effort, HHS has implemented Steps to a HealthierUS , both of which emphasize the importance of physical activity and a nutritious diet. The bone health status of Americans appears to be in jeopardy , a fact that represents another key theme of this report. Fractures due to bone disease are common, costly, and often become a chronic burden on individuals and society. An estimated 1. However, this figure significantly understates the true impact of bone disease, because it captures the problem at a point in time. The impact of bone disease is more appropriately evaluated over a lifetime. Four out of every 10 White women age 50 or older in the United States will experience a hip, spine, or wrist fracture sometime during the remainder of their lives; 13 percent of White men in this country will suffer a similar fate Cummings and Melton While the lifetime risk for men and non-White women is less across all fracture types, it is nonetheless substantial, and may be rising in certain populations, such as Hispanic women Zingmond et al. Fractures can have devastating consequences for both the individuals who suffer them and their family members. For example, hip fractures are associated with increased risk of mortality. The risk of mortality is 2. Those who are in poor health or living in a nursing home at the time of fracture are particularly vulnerable Leibson et al. For those who do survive, these fractures often precipitate a downward spiral in physical and mental health that dramatically impairs quality of life. Nearly one in five hip fracture patients, for example, ends up in a nursing home, a situation that a majority of participants in one study compared unfavorably to death Salkeld et al. Many fracture victims become isolated and depressed, as the fear of falls and additional fractures paralyzes them. Spine fractures, which are not as easily diagnosed and treated as are fractures at other sites, can become a source of chronic pain as well as disfigurement. Osteoporosis is the most important underlying cause of fractures in the elderly. Although osteoporosis can be defined as low bone mass leading to structural fragility, it is difficult to determine the extent of the condition described in these qualitative terms. Left unchecked, the bone health status of Americans is only going to get worse, due primarily to the aging of the population. In fact, the prevalence of osteoporosis and osteoporotic-related fractures will increase significantly unless the underlying bone health status of Americans is significantly improved. By , roughly 12 million individuals over age 50 are expected to have osteoporosis and another 40 million to have low bone mass. By , those figures are expected to jump to 14 million cases of osteoporosis and over 47 million cases of low bone mass NOF These demographic changes could cause the number of hip fractures in the United States to double or triple by Schneider and Guralnik While much less is known about the prevalence and treatment of other bone diseases, they too can have a severe impact on the health and well-being of those who suffer from them, especially if they are not diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. Many of the drugs that are used for osteoporosis are also effective as treatments for other bone diseases. While these diseases cannot be prevented, treatment can reduce levels of deformity and suffering. Further research on osteoporosis is likely to yield additional improvements in the treatment of these diseases, and may even yield insights into how they can be prevented. Not surprisingly, bone disease takes a significant financial toll on society and individuals who suffer from it. Adding in the direct costs of caring for other bone diseases as well as the indirect costs e. Much of this considerable burden can be prevented. There is no question that significant gaps in knowledge and hence research needs remain. However, another important theme of this report is that great improvements in the bone health status of Americans can be made by applying what is already known about early prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. In fact, the evidence clearly suggests that individuals can do a great deal to promote their own bone health. Prevention of bone disease begins at birth and is a lifelong challenge. By choosing to engage in regular physical activity, to follow a bone-healthy diet, and to avoid behaviors such as smoking that can damage bone, individuals can improve their bone health throughout life. Health care professionals can play a critical role in supporting individuals in making these choices and in identifying and treating high-risk individuals and those who have bone disease. As noted earlier, the importance of achieving adequate levels of physical activity and calcium and vitamin D intake is now known, as is the need to begin prevention at a very young age and continue it throughout life. It is never too late for prevention, as even older individuals with poor bone health can improve their bone health status through appropriate exercise and calcium and vitamin D intake. Much is also known about how to ensure timely diagnosis of bone disease. Thanks to the development of bone mineral density BMD testing, fractures need not be the first sign of poor bone health. It is now possible to detect osteoporosis early and to intervene before a fracture occurs. Promising new approaches to assessment and screening will likely provide an even better understanding of the early warning signs of bone disease in the future. On the treatment front, a variety of drugs have been developed that improve bone health and reduce the incidence of fractures. New and potentially more effective drugs are currently under development. There are also promising new directions for the treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta. However, too little of what has been learned thus far about bone health has been applied in practice. As a result, the bone health status of Americans is poorer than it should be. Perhaps the biggest problem is a lack of awareness of bone disease among both the public and health care professionals, many of whom do not understand the magnitude of the problem, let alone the ways in which bone disease can be prevented and treated. Relatively few individuals follow the recommendations related to the amounts of physical activity, calcium, and vitamin D that are needed to maintain bone health. National surveys suggest that the average calcium intake of individuals is far below the levels recommended for optimal bone health Wright et al. Measurements of vitamin D in nursing home residents, hospitalized patients, and adults with hip fractures suggest a high prevalence of insufficiency Webb et al. Many Americans do not engage regularly in leisure-time physical activity. As shown in Chapter 6 , the participation by both adult men and women declines with age, with women being consistently less active than men Schiller et al. In addition, only half those 12—21 years old exercise vigorously on a regular basis and 25 percent report no exercise at all Gordon-Larsen et al. Health care professionals can do a better job as well. Studies show that physicians frequently fail to diagnose and treat osteoporosis, even in elderly patients who have suffered a fracture Solomon et al. For example, in a recent study of four well-established Midwestern health systems, only one-eighth to a quarter of patients who had a hip fracture were tested for their bone density; fewer than a quarter were given calcium and vitamin D supplements; and fewer than one-tenth were treated with effective antiresorptive drugs Harrington et al. Other studies have found low usage rates for testing and treatment among the high-risk population, including BMD testing which ranged from 3—23 percent , calcium and vitamin D supplementation 11—44 percent , and antiresorptive therapy 12—16 percent Morris et al. In fact, most physicians do not even discuss osteoporosis with their patients, even after a fracture Pal Finally, even when physicians do suggest therapy it often does not conform with recommended practice; for example, many patients with low BMD are not treated while others with high BMD are Solomon et al. Managed care organizations and other insurers that provide coverage to individuals under age 65 may not see the full impact of bone disease in their enrollees, since most will have moved on to Medicare by the time they suffer a fracture. Therefore, the commercial providers may not pay sufficient attention to bone health and to the preventive strategies available to and suitable for younger people. In short, therefore, the gap between clinical knowledge and its application in the community remains large and needs to be closed, a fact that represents another key theme of this report. Of particular concern is the fact that some populations suffer additional barriers in trying to achieve optimal bone health. Overcoming these barriers will not be possible without specific strategies and programs geared towards bringing improvements in bone health to these populations. Some of the most important barriers relate to men and racial and ethnic minorities. Osteoporosis and fragility fractures are often mistakenly viewed by both the public and health care practitioners as only being a problem for older White women. This commonly held but incorrect view may delay prevention and even treatment in men and minority women who are not seen as being at risk for osteoporosis. While a relatively small percentage of the total number of people affected, these populations still represent millions of Americans who are suffering the debilitating effects of bone disease. For the poor especially the low-income elderly population , individuals with disabilities, individuals living in rural areas, and other underserved populations, timely access to care represents an additional important barrier. Poor access to care may be caused by any number of factors, such as limited knowledge about bone health; a lack of available providers; inadequate income or insurance coverage; the high costs of diagnosis and treatment; a lack of transportation; or the inability to take time off from work to attend to personal or family care needs. Whatever the causes, the goal of better bone health for all Americans cannot be reached without greater efforts to educate underserved populations about bone health and without significant improvements in their access to appropriate preventive services and counseling, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Today these underserved populations rely on an unorganized patchwork of providers e. Underserved populations not only have difficulty in accessing care, but there are also concerns about the quality of those services they do receive. A recent study by the Institute of Medicine concluded that racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive lower-quality health care than does the majority population, even after accounting for access-related factors Smedley et al. These disparities are consistent across a wide range of services, including those critical to bone health. Moreover, in a large study of older adults who had suffered a hip or wrist fracture, certain groups of patients—including men, older persons, non-Whites, and those with comorbid conditions—were less likely than White women to receive treatment for their bone disease after their fractures Solomon et al. A variety of factors make bone health an ideal candidate for a public health approach. This type of approach can serve as the primary vehicle for improving the bone health status of Americans. To be successful it must involve all stakeholders—individual citizens; volunteer health organizations; health care professionals; community organizations; private industry; and government—and must emphasize policies and programs that promote the dissemination of best practices for prevention, screening, and treatment for all Americans. Some of the work on this public health approach has already begun. The aforementioned Healthy People initiative lays out specific objectives in 28 different areas of health to be achieved during the first decade of the 21st century. Included in these objectives are targets for reducing the number of individuals with osteoporosis and the number of hip fractures, along with increasing levels of calcium intake and physical activity. See Table for more information on those Healthy People goals that relate to osteoporosis and bone health. Developing data systems to track progress on these objectives will be critical to achieving improvements in bone health status. Going forward, it is anticipated that the number of objectives related to osteoporosis and bone health will increase when Healthy People objectives are developed, and that existing measures will be refined as our understanding of the science and our data collection and measurement systems improve. Healthy People Osteoporosis and Bone Health Objectives. Recognizing that bone health can have a significant impact on the overall health and well-being of Americans, Congress instructed that this report cover a range of important issues related to improving bone health, including: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and related bone diseases; the impact of these diseases on minority populations; promising prevention strategies; how to improve health provider education and promote public awareness; and ways to enhance access to key health services. See Appendix A for more details. Department of Agriculture. Following the workshop, a summary of its key findings was released by the Surgeon General Report This report includes contributions from more than 50 authors across the country, while over experts provided valuable guidance and insights in their reviews of initial drafts. This report is intended to be a catalyst for the advancement of research in bone health, and for accelerating the translation of existing evidence on how to improve bone health status into everyday practice. The net result should be an improvement in the bone health status of Americans. This report is based on a review of the published scientific literature. The scope of the review encompassed studies written in English from throughout the world. The quality of the evidence, based on study design and its rigor, was considered as a part of this review. All studies used in the report are referenced in the text, with full citations at the conclusion of each chapter. This report does not offer any new standards or guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of bone disease. Rather, it summarizes knowledge that is already known and can be acted upon. The clinical literature in bone disease includes the full range of studies, from randomized controlled trials to case studies. Comprehensive reviews of the literature have been used for Chapters 2 through 9 , and Chapter Chapter 10 , which is an attempt to summarize key, actionable findings for busy health care professionals, contains few references, as it largely draws on findings cited elsewhere in the report. Chapter 12 draws on both published studies and case studies of population-based initiatives in bone health, which were selected in order to highlight particular lessons about such approaches. Experts in their respective fields of bone health contributed to this report. Each chapter was prepared under the guidance of a coordinating author for that chapter. Independent, expert peer review was conducted for all chapters. The full manuscript was reviewed by a number of senior reviewers as well as the relevant Federal agencies. All who contributed are listed in the Acknowledgments section of the report. This report attempts to answer five major questions for a wide variety of stakeholders, including policymakers; national, State, and local public health officials; health system leaders; health care professionals; community advocates; and individuals. The report is organized around each of these five questions. The first section strives to define bone health and bone disease in terms that the public can understand. The third, fourth, and fifth sections of the report tackle the issue of what can be done to improve bone health—first from the perspective of the individual, then from the perspective of the health care professional, and finally from the perspective of the larger health system. The final section lays out a vision for the future. This introductory part of the report defines bone health as a public health issue with an emphasis on prevention and early intervention to promote strong bones and prevent fractures and their consequences. This first chapter describes this public health approach along with the rationale for the report and the charge from Congress and from the Surgeon General. Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of the fundamentals of bone biology, helping the reader to understand why humans have bones; how bones work; how bones change during life; what keeps bones healthy; what causes bone disease; and what is in store in the future. Chapter 3 offers a summary review of the more common diseases, disorders, and conditions that both directly and indirectly affect bone. Both Chapters 2 and 3 should be considered as important scientific background for the remainder of the report. This part of the report describes the magnitude and scope of the problem from two perspectives. The first is the prevalence of bone disease within the population at large, and the second is the burden that bone diseases impose on society and those who suffer from them. Chapter 4 provides detailed information on the incidence and prevalence of osteoporosis, fractures, and other bone diseases. Where available, it also provides data on bone disease in men and minorities and offers projections for the future. Chapter 5 examines the costs of bone diseases and their effects on well-being and quality of life, both from the point of view of the individual patient and society at large. This part of the report examines factors that determine bone health and describes lifestyle approaches that individuals can take to improve their personal bone health. Chapter 6 provides a thorough review of the evidence on how nutrition, physical activity, and other factors influence bone health, including those behaviors that promote it e. This part of the report describes what health care professionals can do with their patients to promote bone health. Chapter 8 examines the potential risk factors for bone disease; highlights red flags that signal the need for further assessment; reviews the use of formal assessment tools to determine who should get a bone density test; and provides detailed information on how to use BMD for both assessment and monitoring purposes. The chapter also provides a glimpse into the future of bone disease assessment and diagnosis. It includes real-life vignettes that highlight the need for the medical profession to become aware of the potential for severe osteoporosis to develop in younger men and women. Chapter 9 focuses on preventive and therapeutic measures for those who have or are at risk for bone disease. The second level of the pyramid relates to addressing and treating secondary causes of osteoporosis. The third level of the pyramid is pharmacotherapy. The chapter describes currently available anti-resorptive, anabolic therapies and hormone therapies and offers a glimpse into future directions for pharmacologic treatment of osteoporosis. The chapter also reviews the treatment and rehabilitation of osteoporotic fractures and highlights treatment options for other bone diseases. Key symptoms of major metabolic bone diseases are identified, as are red flags that signal a need for further intervention. This part of the report examines how health systems and population-based approaches can promote bone health. Chapter 11 looks at the key systems-level issues and decisions that affect bone health care, including evidence-based medicine; clinical practice guidelines; training and education of health care professionals; quality assurance; coverage policies; and disparities in prevention and treatment. It also evaluates the key roles of various stakeholders in promoting a more systems-based approach to bone health care, including individual clinicians; medical groups; health plans and other insurers; public health departments; and other stakeholders. Chapter 12 describes the various potential components of population-based approaches at the local, State, and Federal levels to promote bone health and reviews the evidence supporting their use. Chapter 12 also draws lessons for bone health from population-based approaches that have been used in other areas of health, such as the National Cholesterol Education Program, to reduce cholesterol levels in Americans. The final part summarizes the key themes of the report, highlights those opportunities that have been identified for promoting bone health, and lays out a vision for how these opportunities can be realized so that bone health can be improved today and far into the future. The key to success will be for public and private stakeholders—including individual consumers; voluntary health organizations and professional associations; health care professionals; health systems; academic medical centers; researchers; health plans and insurers; public health departments; and all levels of government—to join forces in developing a collaborative approach to promoting timely prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of bone disease throughout life. Turn recording back on. National Library of Medicine Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure. Help Accessibility Careers. |

0 thoughts on “Injury prevention and bone health”