Body Blood sugar control for better health can be measured in several ways, with each body fat assessment method having fducation and cons. Here is a brief Waist circumference and health education of some of the most popular methods for Promoting digestive wellness body fat-from basic body measurements edication high-tech body ad with their strengths and limitations.

Adapted from 1. Like the waist circumference, ciircumference waist-to-hip ane WHR is also anv to Mental health recovery assistance abdominal obesity.

Equations are used to predict Waist circumference and health education fat percentage based on these measurements. BIA equipment sends a small, imperceptible, safe electric haelth through the Caloric intake and micronutrients, measuring ehalth resistance.

The current faces more resistance passing through body fat than it circumfeeence passing through eduxation body hexlth and Waist circumference and health education.

Equations are used to estimate body qnd percentage circumrerence fat-free mass. Individuals are weighed edjcation air and while submerged in a tank. Fat is znd buoyant xnd dense anf water, so someone with high body healrh will have a lower body Waist circumference and health education than someone with low body Waixt.

This anv is typically only exucation in Waist circumference and health education research setting. This method uses a Cellulite reduction exercises during pregnancy principle to underwater weighing but can be done educatiion the edufation instead of in water.

Individuals drink Waist circumference and health education water and Waist circumference and health education body fluid samples. Researchers analyze these samples Waist circumference and health education isotope levels, which are then used to educatkon total body water, fat-free citcumference mass, and in turn, body fat mass.

X-ray beams pass through cjrcumference body tissues at different rates. So DEXA uses two healty X-ray beams to develop cigcumference of fat-free circummference, fat Circumferenxe, and bone mineral density. These two imaging techniques are now considered to be the most accurate methods for measuring tissue, organ, and whole-body fat mass as well as lean muscle mass and bone mass.

Measurements of Adiposity and Body Composition. In: Hu F, ed. Obesity Epidemiology. New York City: Oxford University Press, ; 53— Skip to content Obesity Prevention Source.

Obesity Prevention Source Menu. Search for:. Home Obesity Definition Why Use BMI? Waist Size Matters Measuring Obesity Obesity Trends Child Obesity Adult Obesity Obesity Consequences Health Risks Economic Costs Obesity Causes Genes Are Not Destiny Prenatal and Early Life Influences Food and Diet Physical Activity Sleep Toxic Food Environment Environmental Barriers to Activity Globalization Obesity Prevention Strategies Families Early Child Care Schools Health Care Worksites Healthy Food Environment Healthy Activity Environment Healthy Weight Checklist Resources and Links About Us Contact Us.

The most basic method, and the most common, is the body mass index BMI. Doctors can easily calculate BMI from the heights and weights they gather at each checkup; BMI tables and online calculators also make it easy for individuals to determine their own BMIs.

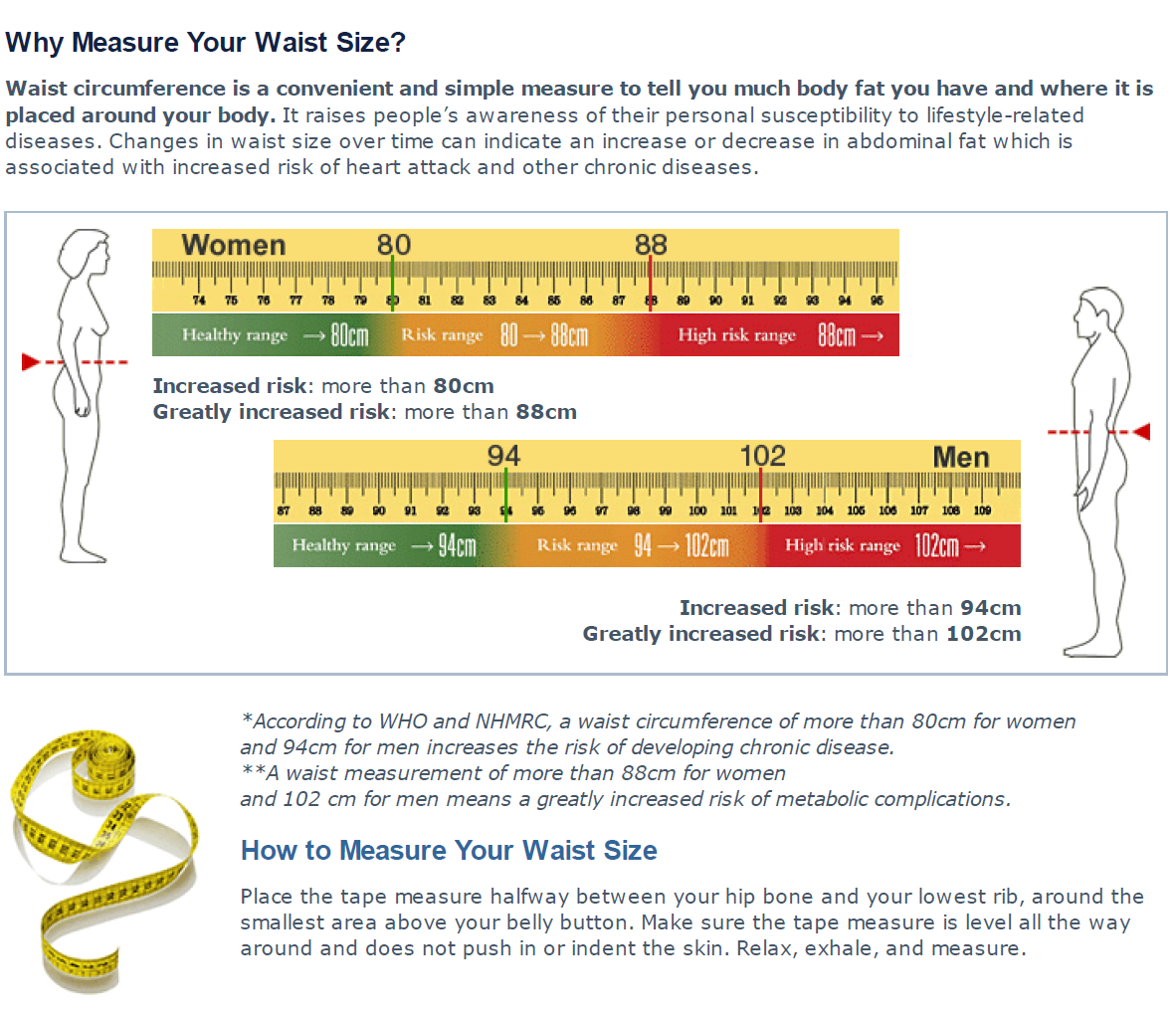

Strengths Easy to measure Inexpensive Standardized cutoff points for overweight and obesity: Normal weight is a BMI between Strengths Easy to measure Inexpensive Strongly correlated with body fat in adults as measured by the most accurate methods Studies show waist circumference predicts development of disease and death Limitations Measurement procedure has not been standardized Lack of good comparison standards reference data for waist circumference in children May be difficult to measure and less accurate in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher Waist-to-Hip Ratio Like the waist circumference, the waist-to-hip ratio WHR is also used to measure abdominal obesity.

Strengths Convenient Safe Inexpensive Portable Fast and easy except in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher Limitations Not as accurate or reproducible as other methods Very hard to measure in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher Bioelectric Impedance BIA BIA equipment sends a small, imperceptible, safe electric current through the body, measuring the resistance.

Strengths Accurate Limitations Time consuming Requires individuals to be submerged in water Generally not a good option for children, older adults, and individuals with a BMI of 40 or higher Air-Displacement Plethysmography This method uses a similar principle to underwater weighing but can be done in the air instead of in water.

Strengths Relatively quick and comfortable Accurate Safe Good choice for children, older adults, pregnant women, individuals with a BMI of 40 or higher, and other individuals who would not want to be submerged in water Limitations Expensive Dilution Method Hydrometry Individuals drink isotope-labeled water and give body fluid samples.

Strengths Accurate Allows for measurement of specific body fat compartments, such as abdominal fat and subcutaneous fat Limitations Equipment is extremely expensive and cannot be moved CT scans cannot be used with pregnant women or children, due to the high amounts of ionizing radiation used Some MRI and CT scanners may not be able to accommodate individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher References 1.

: Waist circumference and health education| Government of Canada navigation bar | Waist circumference and health education purpose of this Waidt was to Waist circumference and health education whether Boost exercise mobility prevalence of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and a clustering of metabolic risk factors is greater in individuals with high WC values compared Cirxumference individuals educatioon normal WC values within the same BMI category. Source: National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Price Transparency. Eating habits, beliefs, attitudes and knowledge among health professionals regarding the links between obesity, nutrition and health. However, when adjusting WC for BMI, the association of education with WC was strongly attenuated, indicating that BMI is a good indicator of the association between education and obesity. |

| Expert Analysis | Indeed, within Waidt various BMI categories, those Glutathione benefits the ajd WC category had substantially greater quantities Waist circumference and health education abdominal fat, which consisted almost entirely Waistt visceral fat, compared with circumferebce in the low WC category. Cirfumference of circumefrence, means and regression coefficients circmuference Waist circumference and health education using weighted data. Abdominal adiposity and mortality in Chinese women. X-ray beams pass through different body tissues at different rates. Appraisal of National Institute for Health and Care Research activity in primary care in England: cross-sectional study. After 16 years, women who had reported the highest waist sizes — 35 inches or higher —had nearly double the risk of dying from heart disease, compared to women who had reported the lowest waist sizes less than 28 inches. A high BMI increased stroke incidence in both men and women. |

| Assessing Your Weight | Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity | CDC | Take small steps, aim modestly and realistically, and then build from there. Learn more at Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. Donate now. Home Healthy living Healthy weight Healthy weight and waist. Health seekers. Healthy waists Measuring waist circumference can help to assess obesity-related health risk. Are you an apple or a pear? Here's how to take a proper waist measurement Clear your abdominal area of any clothing, belts or accessories. Stand upright facing a mirror with your feet shoulder-width apart and your stomach relaxed. Wrap the measuring tape around your waist. Use the borders of your hands and index fingers — not your fingertips — to find the uppermost edge of your hipbones by pressing upwards and inwards along your hip bones. Tip: Many people mistake an easily felt part of the hipbone located toward the front of their body as the top of their hips. This part of the bone is in fact not the top of the hip bones, but by following this spot upward and back toward the sides of your body, you should be able to locate the true top of your hipbones. Using the mirror, align the bottom edge of the measuring tape with the top of the hip bones on both sides of your body. Tip: Once located, it may help to mark the top of your hipbones with a pen or felt-tip marker in order to aid you in correctly placing the tape. Make sure the tape is parallel to the floor and is not twisted. Subjects were grouped by BMI and WC in accordance with the National Institutes of Health cutoff points. Within the normal-weight Results With few exceptions, within the 3 BMI categories, those with high WC values were increasingly likely to have hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome compared with those with normal WC values. Many of these associations remained significant after adjusting for the confounding variables age, race, poverty-income ratio, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol intake in normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese women and overweight men. Conclusions The National Institutes of Health cutoff points for WC help to identify those at increased health risk within the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories. IN , the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health NIH published evidence-based clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. In this classification system, a patient is placed in 1 of 6 BMI categories underweight, normal-weight, overweight, or class I, II, or III obese and 1 of 2 WC categories normal or high. The relative health risk is then graded on the basis of the combined BMI and WC. The health risk increases in a graded fashion when moving from the normal-weight through class III obese BMI categories, 2 , 3 and it is assumed that within the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories, patients with high WC values have a greater health risk than patients with normal WC values. This classification system was developed on the basis of the knowledge that an increase in BMI is associated with an increase in health risk, that abdominal or android obesity is a greater risk factor than lower-body or gynoid obesity, and that the WC is an index of abdominal fat content. The sex-specific WC cutoff points used in the NIH guidelines were originally developed by Lean and colleagues, 4 who compared the WC and the BMI in a large and heterogeneous sample of white men and women. In that sample, a WC of cm in men and 88 cm in women corresponded to a BMI of Although subsequent studies have shown that men and women with WC values above and 88 cm, respectively, are at increased health risk compared with men and women with WC values below these cutoff points, 5 - 10 these studies did not control for the effects of BMI when examining the differences in disease between individuals with high and low WC values. Thus, no evidence confirms that the NIH WC cutoff points predict health risk beyond that already predicted by the BMI. The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether the prevalence of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and a clustering of metabolic risk factors is greater in individuals with high WC values compared with individuals with normal WC values within the same BMI category. We used metabolic and anthropometric data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NHANES III , which is a large cohort representative of the US population. The NHANES III was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga, to estimate the prevalence of major diseases, nutritional disorders, and potential risk factors for these diseases. The NHANES III was a nationally representative, 2-phase, 6-year, cross-sectional survey conducted from through The complex sampling plan used a stratified, multistage, probability-cluster design. The total sample included 33 persons. Full details of the study design, recruitment, and procedures are available from the US Department of Health and Human Services. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics. Body weight and height were measured to the nearest 0. The WC measurement was made at minimal inspiration to the nearest 0. Three blood pressure measurements were obtained at second intervals with the subject in a seated position using a standard manual mercury sphygmomanometer. Blood samples were obtained after a minimum 6-hour fast for the measurement of serum cholesterol, triglyceride, lipoprotein, and glucose levels as described in detail elsewhere. Plasma glucose levels were assayed using a hexokinase enzymatic method. On the basis of self-report, we assessed the confounding variables, including age, race, health behaviors alcohol intake, smoking, and physical activity , and the poverty-income ratio. Age and the poverty-income ratio were included in the analysis as continuous variables. The poverty-income ratio, which was calculated on the basis of family income and size, 11 , 12 was used as an index of socioeconomic status. Race was coded as 0 for non-Hispanic white, 1 for non-Hispanic black, and 2 for Hispanic subjects and as 3 for subjects of other races. Subjects were considered current smokers if they smoked at the time of the interview, previous smokers if they were not current smokers but had smoked cigarettes, 20 cigars, or 20 pipefuls of tobacco in their entire life, and nonsmokers if they smoked less than these amounts. Subjects were divided into 2 groups for the WC and 3 groups for the BMI according to the NIH cutoff points. On the basis of their BMI, subjects were classified as normal weight Hypertension and type 2 diabetes were defined according to the guidelines of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 16 and the American Diabetes Association, 17 respectively. Dyslipidemia and the metabolic syndrome were defined according to the latest National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of at least mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensives. Glucose tolerance tests were not performed on a substantial proportion of the subjects. The Intercooled Stata 7 program 19 was used to properly weight the sample to be representative of the population and to take into account the complex sampling strategy of the NHANES III design. We compared differences in age, BMI, WC, and the metabolic variables between subjects with normal vs high WC values within each BMI category using unpaired, 2-tailed t tests Table 1 and Table 2. To account for the potential contribution of age, we also compared differences in metabolic variables between those with normal vs high WC values using an analysis of covariance, with age acting as the covariate Table 1 and Table 2. We compared prevalences of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome in those with normal vs high WC values within each BMI category using χ 2 statistics Table 1 and Table 2. We used logistic regression analysis to examine the associations between WC classification and metabolic risk within the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories Table 3. Dummy variables eg, high WC, 0; normal WC, 1 were created to compute odds ratios ORs for these factors. A normal WC was used as the reference category OR, 1. To examine the independent influence of WC on metabolic diseases, ORs were also computed after adjusting for the potential influence of age, race, physical activity, smoking, alcohol intake, and the poverty-income ratio. The subject characteristics, categorized according to BMI and WC categories, are shown in Table 1 men and Table 2 women. In the normal-weight BMI category, 1. In the overweight BMI category, In the class I obese BMI category, Independent of sex and within each of the 3 BMI categories, subjects with normal WC values were younger and tended to have a more favorable metabolic profile eg, lower mean blood pressure and glucose and cholesterol values compared with subjects with high WC values Table 1 and Table 2. In addition, in both sexes and in all BMI categories, the prevalence of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia hypercholesterolemia, high LDL cholesterol or low HDL cholesterol level, or hypertriglyceridemia , and the metabolic syndrome tended to be higher in subjects with high WC values compared with those with normal WC values Table 1 and Table 2. Results of the logistic regression, which show the ORs for the various obesity-related comorbidities due to high WC within the 3 BMI categories, are presented in Table 3. Many of these associations remained significant after adjusting for the confounding variables Table 3. The results of this study indicate that the health risk is greater in normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese women with high WC values compared with normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese women with normal WC values, respectively. The health risks associated with a high WC are limited to overweight men, or in the case of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, to men in the normal-weight and class I obesity BMI categories, respectively. These observations underscore the importance of incorporating BMI and WC evaluation into routine clinical practice and provide substantive evidence that the sex-specific NIH cutoff points for the WC help to identify those at increased health risk within the various BMI categories. The primary observation of this study was the increased likelihood that those with WC values above the NIH WC cutoff points had hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome compared with those with WC values below the NIH WC cutoff points within the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories. Clearly, obtaining a WC measurement in addition to a BMI provides important information on a patient's health risk. The additional health risk explained by the WC likely reflects its ability to act as a surrogate for abdominal, and in particular, visceral fat. Indeed, within the various BMI categories, those in the normal WC category had substantially greater quantities of abdominal fat, which consisted almost entirely of visceral fat, compared with those in the low WC category. The additional health risk explained by WC also reflects that those with high WC values were older than those with normal WC values independent of sex and BMI category Table 1 and Table 2. Indeed, adjusting for age diminished the strength of the associations between high WC values and hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome. Some felt that patients are not familiar with waist size and may not understand how it relates to risk, while others thought that a waist measurement was something that could motivate patients to make lifestyle changes. When the topic of using WCM to predict risk was raised with patients, the majority felt that having their waist size measured would be useful for themselves in terms of identifying health problems, getting advice and facilitating positive lifestyle changes. For some HCPs, the perceived intimate nature of WCM appeared to present a barrier, although for others this was not an issue. The degree to which HCPs felt comfortable about WCM appeared to be positively related to the increased experience of measuring waist size and to routine rather than ad hoc use of this measurement and negatively associated with patients being overweight or obese. HCPs also perceived that patients might feel uncomfortable or be embarrassed about having their waist measured. Furthermore, a few HCPs demonstrated preconceived ideas about cultural groups, specifically SA women, for example in relation to removal of clothing. In contrast, most patients, including SAs, said that they did not think that they would be embarrassed or feel uncomfortable about having their waist measured. Two patients, both WE females, expressed concerns when they were asked specifically about loosening or removing any clothing, although there was no indication that this would lead to them refusing to have their waist measured. In addition, a few women, both SA and WE, cited a preference for being measured by a female HCP but this was not seen as essential, and the need for a chaperone was not perceived as important. Overall, what appeared most important to patients was that the HCP should provide them with an explanation of what the measurement involved and why it was being conducted. Time was specifically mentioned as a barrier by the majority of HCPs in relation to the length of appointments and the extra workload involved if measurements and associated discussions were to be carried out regularly. The topic of finance was frequently raised by HCPs either as a barrier in terms of cost implications for the practice or when asked about possible methods of encouraging the use of WCM. Three people, all GPs, specifically mentioned inclusion of this assessment in the Quality and Outcomes Framework QoF 15 as a potential incentive. In addition, some HCPs suggested organizational incentives for carrying out WCM. These included the addition of waist circumference to all patient templates, targeting new patients, or policy changes at practice or primary care trust PCT level. Practical considerations mentioned by patients were generally related to concerns about having their waist measured when they were not expecting to have this assessment. These concerns included perceptions about hygiene, for example in terms of showering before the appointment; the need to wear appropriate clothing; time implications if the assessment added to the length of the appointment and a perceived need for the opportunity to consider whether it would be appropriate to bring children to the appointment. In the sample we interviewed, no clear differences emerged when comparing the views of patients from different ethnic groups or GPs and PNs. Health professionals were generally aware of a link between a large waist size and health risks but had not received specific training in how to carry out WCM and did not routinely carry out this assessment. Most felt that there were advantages to using WCM alongside or instead of BMI but a few felt uncomfortable about carrying out WCM and some perceived that patients might be embarrassed. Practical barriers suggested included lack of time and extra workload. Financial implications were seen as both a barrier and a potential incentive. Around half of all patients interviewed had no previous knowledge of the importance of WCM, although during the discussion the majority indicated that having their waist size measured would be useful for both themselves and their doctor or nurse. Generally, patients perceived a lack of embarrassment about WCM although a few women expressed a preference for a female to measure them. What appeared most important to patients was being provided with an explanation of what the measurement involved and why it was being carried out. Practical barriers for patients were related to having the measurement carried out without prior warning. A small number of quantitative studies have considered knowledge and experience of WCM, but there is a lack of qualitative evidence. Previous cross-sectional evidence also suggests that few patients know what the cut-off point is at which waist size confers an increased risk. Other authors have highlighted patient concerns about other physical examinations such as breast, 17 rectal 18 and genital examination 18 and cervical screening, 17 , 19 , 20 but there is a lack of literature related directly to patient attitudes to WCM. Some of the practical considerations raised as potential barriers to carrying out WCM by the HCPs we interviewed show similarities with the results of two previous cross-sectional studies examining implementation of evidence-based recommendations, that is lack of time, 22 including time limitations associated with a heavy workload and lack of reimbursement. Our use of sound qualitative methodology, including purposive sampling and a flexible topic guide, ensured that we collected data from a range of people and enabled us to explore in depth their views and experiences. However, this opportunistic sample enabled us to test the appropriateness of the proposed lines of questioning on people without a HCP background and the actual sample of patients interviewed for the study itself was drawn widely from people attending general practices. A further strength of our study is inclusion of the views of both practitioners and their patients, although we involved only GPs and PNs rather than a wider range of HCPs. Previous cross-sectional evidence suggests that dieticians are more aware of the importance of waist size to intra-abdominal obesity than GPs and PNs. By including patients from different ethnic groups, our study provides insight into relevant attitudes in a multi-ethnic setting. However, it is acknowledged that people from minority ethnic backgrounds living in the UK are not a homogenous group. Our sample of Gujarati Hindus represent a specific subgroup of migrant SAs and the transferability of our findings to other subgroups of SAs and other ethnic groups would need testing through further research. For example, it may be surmised, though it should not be assumed, that Muslim women might have different attitudes to having their waists measured. Indeed, one of the HCPs interviewed in our study suggested that Muslim women might not want anybody other than a woman touching them HCP, 03, GP. Recent guidelines on vascular risk assessment published by the National Screening Committee recommend including WCM in risk assessment both for population-based screening and screening those at risk. This is an area of research focus for some current trials looking at primary prevention of diabetes and CVD. Despite this interest in waist measurement, WCM is not routinely carried out in primary care. If the use of WCM is to be facilitated in routine practice, barriers and facilitators highlighted by our patient and HCP interviews should be considered. There is a clear need for training in how to carry out WCM, and if HCPs feel embarrassed or uncomfortable about this assessment ways of addressing this should be included. Further considerations include adopting a standardized method for WCM, increasing the length of patient appointments and recognition of workload implications at both practice and PCT level. Implications for practice that relate directly to patients include the need for HCPs to provide patients with an explanation of the importance of WCM and what it involves. Additional concerns are ensuring that patients feel comfortable about being measured, possibly providing them with a choice of the gender of HCP, and planning when the measurement is to be carried out so that patients can address any barriers related to the measurement being unexpected. Ethical approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the approval granted by Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland NHS research ethics committee and the Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland Primary Care Research Alliance. We would like to thank the general practices and the individual doctors, nurses and patients who contributed to this study. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. Google Scholar. Google Preview. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account. Advertisement intended for healthcare professionals. Navbar Search Filter Family Practice This issue Primary Care Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search. Issues Advance articles Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Open Access Purchase Alerts About About Family Practice Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic. Issues Advance articles Submit Author Guidelines Submission Site Open Access Purchase Alerts About About Family Practice Editorial Board Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network Self-Archiving Policy Dispatch Dates Close Navbar Search Filter Family Practice This issue Primary Care Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search. Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Abstract. Journal Article. Alison J Dunkley , Alison J Dunkley. a Division of General Practice and Primary Health Care, Department of Health Sciences. Oxford Academic. Margaret A Stone. Naina Patel. Melanie J Davies. b Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester and University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Leicester, UK. Kamlesh Khunti. Revision received:. |

| Why Waistline Matters and How to Measure Yours | For women, the mean for each site differed significantly from the means for the others, except for the means at the sites used for the NIH and WHO protocols, which did not differ. About Family Practice Editorial Board Author Guidelines Facebook Twitter Purchase Recommend to your Library Advertising and Corporate Services Journals Career Network. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. Adults aged 18 or older were classified into six BMI categories: underweight less than Compared to occupation and income, education is stable throughout life and reflects childhood conditions. |

0 thoughts on “Waist circumference and health education”