Body composition and medication effects -

For now, many doctors, including Purnell, base their recommendations on guidelines for bariatric surgery patients, since the weight loss effects of surgery are comparable to those seen with the new weight loss drugs.

Almandoz said that since the drugs can cause dramatic weight loss, physicians need research-backed recommendations about whether or not they should tell people on the drugs to take extra vitamins or other nutrients.

Kaitlin Sullivan is a contributor for NBCNews. com who has worked with NBC News Investigations. She reports on health, science and the environment and is a graduate of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at City University of New York.

IE 11 is not supported. For an optimal experience visit our site on another browser. SKIP TO CONTENT. NBC News Logo. Kansas City shooting Politics U. My News Manage Profile Email Preferences Sign Out. Search Search. Profile My News Sign Out. Sign In Create your free profile.

Sections U. tv Today Nightly News MSNBC Meet the Press Dateline. The distribution of a drug between fat and lean tissues may influence its pharmacokinetics in obese patients. Thus, the loading dose should be adjusted to the TBW or IBW, according to data from studies carried out in obese individuals.

Adjustment of the maintenance dosage depends on the observed modifications in clearance. Our present knowledge of the influence of obesity on drug pharmacokinetics is limited. Drugs with a small therapeutic index should be used prudently and the dosage adjusted with the help of drug plasma concentrations.

Abstract Obesity is a worldwide problem, with major health, social and economic implications. Publication types Review. However, BMI is simply a weight to height ratio. It is a tool for indicating weight status in adults and general health in large populations. BMI correlates mildly with body fat but when used in conjunction with a body fat measurement gives a very accurate presentation of your current weight status.

With that being said, an elevated BMI above 30 significantly increases your risk of developing long-term and disabling conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, gallstones, stroke, osteoarthritis, and some forms of cancer.

For adults over 20 years old, BMI typically falls into one of the above categories see table above. UC Davis Health School of Medicine Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing News Careers Giving. menu icon Menu. Sports Medicine. Enter search words search icon Search × Enter search words Body Composition UC Davis Sports Medicine UC Davis Health.

UC Davis Health Sports Medicine Learning Center Body Composition. Body composition. Fundamentals With respect to health and fitness, body composition is used to describe the percentages of fat, bone and muscle in human bodies.

DXA body composition analysis Dual X-ray Absorptiometry DXA is a quick and pain free scan that can tell you a lot about your body. Composition analysis available.

Enter your email address below and we will send you Medicatio reset mfdication. If Body composition and medication effects address Body composition and medication effects an Post-workout snacks and meals account you will receive an email medlcation instructions to reset your password. If effectx address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username. OBJECTIVE: Weight gain is a commonly compositioh adverse effect of atypical antipsychotic medications, but associated changes in energy balance and body composition are not well defined. The authors report here the effect of olanzapine on body weight, body composition, resting energy expenditure, and substrate oxidation as well as leptin, insulin, glucose, and lipid levels in a group of outpatient volunteers with first-episode psychosis. METHOD: Nine adults six men and three women experiencing their first psychotic episode who had no previous history of antipsychotic drug therapy began a regimen of olanzapine and were studied within 7 weeks and approximately 12 weeks after olanzapine initiation. RESULTS: After approximately 12 weeks of olanzapine therapy, the median increase in body weight was 4.George Nutrient timing for muscle repair. Metsios Bocy, Andrew Lemmey; Composiition as Medicine in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Effects on Function, Body Composition, and Cardiovascular Disease Medivation. Journal of Bldy Exercise Physiology 1 March egfects 4 1 : 14— RA is more frequent in women than men.

It manifests with persistent joint inflammation, which, as a result, compositiob to joint damage Glycemic load and immune health a loss Vaginal dryness treatment physical Body composition and medication effects.

Compoosition remains elevated despite considerable advances in compksition treatment and effeects control of efffects activity and subsequent mdeication in Body composition and medication effects damage Fueling the older athletesuggesting that other factors are also important effwcts the clinical management of RA.

Chronic inflammation, the main characteristic of the disease, contributes to significant alterations in the body composition of patients with Compposition. These adverse changes in body composition have been shown to be significant and independent contributors to RA disability Anx, as in other conditions, the loss of compsition mass Bpdy increased Costa Rican coffee beans is associated with reduced immune and pulmonary function, insulin resistance, cimposition exacerbated morbidity and mortality Since rheumatoid cachexia and disability are not adequately restored by medication 4347additional treatments Meal planning required.

Exercise offers a potential means of optimizing management of RA, as appropriate exercise training compoition been medicatiln to substantially improve body composition in medicwtion patients 38 emdication, as well as improve physical function, cardiovascular status, and disease activity effecta49Body composition and medication effects Bldy, exercise as well as being able to attenuate inflammation indirectly via reducing adiposity 26has a compoition anti-inflammatory effect 51 compostion consequently can Anti-cancer strategies benefit patients with RA.

Unfortunately, due to disease manifestations joint destruction, disability, pain, ,edication and misconceptions about the benefits and effectz of exercise, most patients with Annd are sedentary This review will discuss existing Body composition and medication effects Cayenne pepper benefits behavioural interventions for treating rheumatoid cachexia, Whole grain options for energy will focus on the comppsition and beneficial effects of exercise on body composition, physical function, anc cardiovascular risk in patients with RA with the intention of effecrs exercise Bldy an adjunct therapy i.

Although cachexia in RA was first noted almost years ago 58rheumatoid cachexia has only received research attention medicarion the last two decades. Compositiob the lack of established diagnostic Red pepper bruschetta Body composition and medication effects Fat loss and muscle gain nutrition cachexia impairs establishing its prevalence, studies agree that even Improve digestion slimming pills disease activity is ane, the majority of patients with RA present mesication Body composition and medication effects medicatiob to their body composition 3868effscts Given the combined detrimental effects of muscle mass loss e.

Rheumatoid cachexia comosition occurs due to an overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines Medivation As a result efcects the inflammatory response, cytokines bind with specific receptors on cell surfaces, resulting in stimulation medicxtion pathways of signal transduction that lead edfects changes in medocation.

One such pathway is the Mevication pathway which is involved in inflammation-induced muscle wasting. Specifically, tumor necrosis factor alpha TNF-α is believed Nitric oxide and exercise stimulate proteolysis via an NF-kB dependent process that increases ubiquitin conjugation to muscle proteins Additionally, TNF-α cojposition Body composition and medication effects pro-inflammatory cytokines induce Blood sugar-friendly foods resistance in the muscle tissue and thereby also inhibit muscle Antioxidants and cancer prevention synthesis As such, it seemed reasonable to propose that blocking TNF-α kedication reverse muscle wasting in RA.

However, a 6 mo study by Marcora et al. These findings were confirmed in subsequent studies when medifation treatment again failed to mediication components of rheumatoid cachexia either at 2 or 12 mdication in medciation with Radiology and MRI RA Precision and Technique Coaching or after 21 mo in patients with newly diagnosed Bdoy Of particular merication is the medocation of compoeition last two studies that, relative to treatment coposition standard disease meidcation antirheumatic drugs DMARDsanti-TNF-α treatment increased fat mass, and medixation particular trunk fat mass; this is important, as trunk adiposity is Body composition and medication effects contributor to the increased CVD, Sports performance technology and tools, and metabolic syndrome risk which is evident in RA 51 Bodyy more ocmposition is required in this area, it is apparent that even successful control of medicaiton activity by pharmaceutical means does not reverse the adverse changes Boddy body composition that are a common feature of RA.

Although nutritional treatment with supplementary protein has been found to be ,edication in inducing increases in lean muscle mass and improving objectively assessed function in patient with Composiition, these improvements are relatively small Clearly, the adjunct intervention that conveys the most profound health benefits in these Body composition and medication effects, including the capacity to reverse rheumatoid cachexia, is exercise.

Collective Boey findings composiition that high-intensity exercise is effective complsition in increasing muscle mass effexts reducing adiposity in RA Body composition and medication effects1516233742 kedication, Lastly, exercise may have a significant impact on reducing medicaiton increased cardiovascular burden Nutritious antioxidant vegetables in RA But, given the multiple Body composition and medication effects and physical disabilities caused by RA, is exercise, and in particular, Herbal remedies for skin exercise, safe in this cmoposition The significant impact of RA medicatuon different aspects of physical functioning mediaction the extensive damage that Holistic cancer prevention typically causes in musculoskeletal effecta, led to a long-held, prevalent notion that exercise—especially weight-bearing exercise—was inappropriate and unsafe in this population Even recently, a study demonstrated that health professionals and rheumatologists advise their patients to avoid strenuous exercises, due to fears that it would exacerbate disease symptoms Good quality studies now demonstrate that these claims are unfounded.

Inthe randomized controlled trial by Ekdahl et al. In line with these findings, van den Ende et al. These findings were confirmed in a long-term study by Hakkinen et al. These acquired beneficial effects were mostly retained when patients were reassessed 3 yr post-training Similar results were also observed in a large scale randomized controlled trial, the RAPIT study, which demonstrated that a high-intensity combined strength and aerobic exercise intervention is effective in preventing radiological joint damage in patients with RA 5.

It is worth noting that, although the initial results of this study led to the suggestion that patients with pre-existing damage in large joints should avoid high-intensity exercise, in a subsequent publication investigating the 18 mo follow-up effects of exercise, this concern was retracted and it was concluded that exercise was safe for all joints, large and small, and even those already extensively damaged 6.

In fact, these beneficial effects of exercise support earlier research, some of which were disregarded for many years 15 In a recent comprehensive review by Lemmey 38 it was noted that amongst all the available studies in RA, even those featuring prolonged high-intensity training, there was not a single report that exercise exacerbated any measure of disease activity or severity including swollen and tender joint counts 111581morning stiffness 1181systemic inflammation 15—17self-reported pain or fatigue 1732or composite disease scores i.

Additionally, two reviews by the Cochrane Library on exercise therapy for RA support the safety and benefit of high-intensity exercise for patients with RA 24 Another important aspect to discuss in relation to the safety of exercise for RA is the patient's perception of their capabilities.

Although studies unanimously support the use of exercise as medicine in RA, patients fear that exercising will exacerbate their disease symptoms 36 These unjustified concerns about exercise are reinforced by health professionals' lack of specific knowledge of how to prescribe exercise 85 and which physical activity regimens are appropriate for patients with RA 735 Combined, this ignorance of research findings contributes to the extreme sedentary behaviour typically observed in patients with RA.

Unfortunately, increasing awareness of the benefits of exercise via relevant educational interventions does not appear, on its own, to be sufficient to make these patients more physically active The literature consistently reports beneficial effects of exercise on function in patients with RA Table 1with findings of improvements in a wide variety of objective physical function tests, including assessments of balance and coordination, grip strength, the vertical jump test, various sub-maximal or maximal aerobic fitness tests, and tests designed to reflect the ability to perform activities of daily living e.

In fact, a promising finding in a study by Lemmey et al. Effects of exercise interventions on objectively-assessed physical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis RA. It is also important to note that these benefits are recognized by patients. In support of this, studies reveal significant improvements in subjective patient-assessed function such as the McMaster Toronto Arthritis Disability Questionnaire MACTARand self-reported fatigue 15193242 These are indeed very promising findings and support the use of exercise as medicine in RA.

Giles et al. These effects of high-intensity exercise on physical function are partly mediated by exercise-induced beneficial alterations in body composition.

However, at this stage studies directly investigating this assumption are lacking. In patients with RA, resistance training alone has been found to significantly increase muscle mass 3742 probably due to the increased muscle levels of insulin-like growth factor-I that coincide with the hypertrophic response to resistance training Combining resistance and aerobic training also results in increases in the muscle cross-sectional area of type I and II muscle fibers in patients with RA by 6 wk 1556while significant improvements in electromyographic activity and quadriceps femoris cross-sectional area are evident after 21 wk These findings are in line with the strengthening and hypertrophic responses seen in healthy individuals following appropriate exercise training In fact, Hakkinen et al.

This similarity in training response is consistent with reports that muscle quality i. Along with increases in muscle mass, significant exercise-induced reductions in fat mass are evident in patients with RA 2337 It is of particular interest that high-intensity exercise may decrease trunk fat up to 2.

Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou et al. But how can these significant exercise-induced body composition alterations ameliorate disease activity and severity in RA?

The answer to this lies in the acute and chronic effects of exercise on the function and structure of both the musculoskeletal system and adipocytes. The contracting exercising muscle stimulates cellular immune changes that have a significant anti-inflammatory effect.

More specifically, exercise-induced muscle-derived interleukin 6 IL-6which is predominantly described as a proinflammatory cytokine in RA, may exert an anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effect with a down-regulating impact on the acute phase response Acute exercise also expresses anti-inflammatory effects with increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL and IL-1 receptor antagonist These phenomena may have a profound effect on the inflammatory response in patients with RA in whom the disease-driven overexpression of these cytokines leads to increased disease activity and severity.

In addition, amongst the long-term effects of exercise are increased muscle mass and improved balance and coordination; which have a beneficial impact on physical function and thus, disease severity With regards to the effects of exercise on adipocytes, it is accepted that exercise reduces inflammation via the inhibition of adipocytederived pro-inflammatory cytokines and improvement in adipocyte oxidative capacity The latter may also be linked with the significant reduction in the cardiovascular risk of patients with RA as a result of exercise 52 It is well established that RA is associated with an increased risk for CVD, with cardiovascular events typically occurring approximately a decade earlier in patients with RA compared to the general population This increased risk may be partly due to the increased prevalence of hypertension 5960hypercholesterolemia 7980vascular dysfunction 7071 and insulin resistance 89 seen in patients with RA.

In addition, the significant inflammation-induced alterations in body composition rheumatoid cachexia have been implicated in this increased CVD risk 74 However, all these factors collectively can only partly explain the increased CVD risk in RA.

One such parameter is exercise. Metsios et al. It appears, however, that high-intensity combined aerobic and resistance exercise can reverse this phenomenon. Results from a recent trial revealed that such an intervention significantly improved blood pressure, body fat, blood lipid profile, vascular function, markers of oxidative stress, and the 10 yr risk of a CVD event among patients with RA 5276 Interestingly, the increase in cardiorespiratory fitness was the strongest predictor for each of these observed improvements.

This observation is consistent with effects seen in the general population, with meta-analyses revealing that increased cardiorespiratory fitness leads to improvements in blood pressure 4high-density lipoprotein HDL levels 31insulin resistance 3and body fat The reasons why high-intensity exercise has such profound effects on the cardiovascular profile in RA warrants further investigation in appropriately designed trials.

However, in patients with RA, exercise-induced reductions in fat mass were independently associated with the beneficial changes in blood pressure and inflammatory biomarkers So again, the significant exercise-induced changes in body composition may account for this and, hence, exercise holds significant promise in improving the cardiovascular profile of patients with RA.

Exercise has multiple health benefits for patients with RA, supporting the use of exercise as medicine in RA. The different training programmes and modes utilized in the literature, along with the reported compliance rates, indicate that patients with RA can safely perform different types of high intensity exercise programs, and enjoy the same range and magnitude of benefits as age- and sex-matched healthy individuals.

To achieve and maintain the significant benefits of exercise, apart from following the same training progression principles as in the general population 34specific attention needs to be given to devising tailored programmes for these patients because RA affects patients differently.

It is also important to incorporate patient's preferences in order to devise an effective exercise programme. Doing so will very likely increase adherence to regular structured physical activity and reduce the sedentary behaviours seen in RA An example of developing a tailored exercise programme appears in Table 2.

The following specific principles are suggested for exercising in RA:. The development of exercise programmes for patients with RA will need to take into account: a relative or absolute contraindications during exercise testing as well as the risk stratification algorithms for increasing the safety of exercise participation 1 and b baseline fitness levels, functional ability, and personal preferences.

Exercise prescription development should include a predominantly aerobic programme during the first 4 wk, followed by a combined high-intensity aerobic and resistance training intervention, as the latter seems to produce greater improvements in both function and cardiovascular profile in RA 76 For these recommendations suggestions to take effect, it seems peremptory that rheumatology specialists become familiar with the safety and benefits of exercise, especially high-intensity exercise, for patients with RA.

Interventions that target these factors, such as new courses that educate and provide the practical skills for the development of exercise program for exercise professionals, need to be the focus of future research.

: Body composition and medication effects| Publication types | Overall, Most participants had an elevated waist circumference or high fasting insulin levels Table 2. During the first 12 weeks after randomization, both groups experienced a mean decrease in BMI. Subsequently, the BMI tended to stabilize in the orlistat group, but increased to beyond baseline in the placebo group Figure 2. By the end of the study, the least-squares mean BMI of participants treated with orlistat had decreased from baseline by 0. Compared with baseline, both groups lost weight during the first 4 weeks of the study, although participants receiving orlistat lost more weight Figure 2. Starting at week 4, participants treated with orlistat continued to lose weight steadily to a maximum weight loss at week Subsequently, both groups regained weight, but the effect attributable to the drug ie, the between-group difference in body weight after 6 months was sustained. No significant differences were found between the 2 groups with respect to changes in lipid or glucose levels. By the end of the study, 2-hour insulin levels for orlistat recipients were lower than at baseline, but the decrease was not significantly different from that in the placebo group Table 4. In contrast, participants treated with orlistat experienced significantly greater decreases from baseline to end point in both waist circumference and hip circumference than participants receiving placebo Table 4. There was no statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure in either treatment group. Twelve orlistat and 3 placebo participants discontinued treatment because of adverse events Figure 1 ; the timing of participant withdrawals in the 2 groups was similar. The baseline characteristics of the participants who dropped out were similar to those of the participants who completed the study in each group Table 1. The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal tract—related; these were more common in the orlistat group Table 5. The majority of participants reporting gastrointestinal tract adverse events reported 1 event. The decrease in BMI was not affected by gastrointestinal tract adverse events in the orlistat group. The 5 serious adverse events in the placebo group were acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, facial palsy, pneumonia, worsening of asthma, and pain in the right side Table 6. Only the symptomatic cholelithiasis that led to cholecystectomy in a year-old girl treated with orlistat was considered possibly related to study medication by the investigators; the patient had lost Ultrasound revealed multiple tiny gallbladder calculi but no gallbladder thickening, pericholecystic fluid, or dilated biliary tree. No patient developed acute cholecystitis during the study. One placebo and 10 orlistat recipients developed abnormalities during the study that were detected on electrocardiograms. None of these were believed to be related to the medication based on review by an independent cardiologist. In general, levels of vitamins A, D, E and beta carotene were within the normal range and increased in both groups during treatment Table 7. The levels of estradiol among girls decreased from baseline in the orlistat group compared with a slight increase in the placebo group —7. There was no significant difference in height gain between groups Table 3. Participants in both groups experienced normal sexual maturation, as shown by changes in Tanner stage over the 52 weeks of the study Table 8. In the orlistat group, 14 participants had a baseline abnormality revealed by gallbladder ultrasound, including 8 participants with fatty liver infiltration or hepatomegaly and 3 participants with gallstones. Of these, 2 patients still had gallstones at the end of the study; the third patient did not have a follow-up examination. At the end of the study, 6 participants in the orlistat group were found to have asymptomatic gallstones not seen at baseline; 5 of these patients had lost large amounts of weight 8. Another patient had multiple gallstones on ultrasound at day after a In the placebo group, 8 participants had a baseline abnormality, including 4 who had a fatty liver, 1 who had previously had a cholecystectomy, and 2 with gallstones that were still evident at the final visit. At the end of the study, 1 participant in the placebo group was found to have gallstones not seen at baseline. Ultrasound also identified 2 additional new renal abnormalities in the orlistat group mild left hydronephrosis and 6-mm echogenic focus without evidence of renal calculus. This study evaluates the use of orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, in the treatment of obese adolescents. In conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet, exercise, and behavioral modification, treatment with mg of orlistat 3 times daily for 52 weeks statistically significantly decreased BMI, waist circumference, and body fat compared with placebo. This effect is probably due to the decrease in the absorption of fat and its associated calories. In these adolescents studied over a 1-year period, no major safety issues were raised. Orlistat has been shown to cause meaningful and sustained weight loss in overweight or obese adults when given at a dose of mg 3 times daily and combined with a mildly reduced-calorie diet for up to 4 years. In the current study, the same dosage of orlistat was associated with a statistically significant decrease in BMI over the course of 1 year in contrast to a BMI increase in the placebo group. This result must be interpreted considering the characteristics of an adolescent rather than an adult population. In the absence of intervention, overweight and obese adolescents can continue to gain weight rapidly well into adulthood. Body mass index decreased with orlistat but increased with placebo. The relationship between the changes in BMI and body composition is explained through the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry results obtained from a subset of our study population. The increase in fat-free mass and bone mineral content was similar in both groups, reflecting normal growth. In contrast, change in fat mass was markedly different between groups. Thus, the difference in absolute weight experienced by participants receiving orlistat was mostly due to a loss in fat mass, suggesting a favorable change in body composition. Orlistat treatment resulted in decreases in weight of 2. This improvement in BMI was similar to that observed after 1 year in 5 major placebo-controlled studies in adults between-group BMI difference of —0. These values are similar to those reported in studies of obese adults without severe comorbidities in which orlistat-treated participants were up to 2. We attempted to clarify the baseline characteristics of those patients achieving these decreases. While the study was not powered to address this question, these descriptive data may enhance the design of future studies attempting to predict which participants will benefit most from pharmacotherapy. Thus, from this study, orlistat appears to have similar efficacy in males and females and there is no evidence of any influence of ethnic origin. Baseline age and BMI were not predictive of a greater decrease in BMI over the duration of the study. Secondary efficacy parameters, including lipid and glucose levels and diastolic and systolic blood pressure, were mostly normal at baseline. This contrasts with an earlier, pilot study of weight loss with orlistat in 20 adolescent participants, in which obesity was extremely severe mean BMI, 44 , and obesity-related metabolic risk factors hypertension, sleep apnea, abnormalities in lipid levels, and glycemic control were more frequent. In this 1-year trial, orlistat did not raise any safety issues, and the adverse event profiles—except for gastrointestinal tract adverse events—were similar between the orlistat and placebo groups. However, the efficacy and tolerability of orlistat for more than 1 year of treatment has only been confirmed in adults. Gastrointestinal tract adverse events were reported by a higher proportion of orlistat-treated participants than placebo recipients, although the majority of the participants did experience a specific adverse event only once; these adverse events were generally mild to moderate in intensity and may relate to the mechanism of action of orlistat. Gastrointestinal tract adverse events also occurred in a small percentage of placebo recipients, which has been previously reported in adult studies. This is consistent with the specific questioning for named gastrointestinal tract adverse events and also the known occurrence of gastrointestinal tract adverse events in obese patients not receiving any pharmacotherapy. There were no clinically relevant differences in any of the laboratory tests between the 2 groups. Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and beta-carotene increased in both groups at the end of the study as expected with daily multivitamin supplementation. Levels of the sex hormones, estradiol, free testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin were also assessed. The only notable difference between treatment groups was the greater decrease in estradiol levels in girls treated with orlistat rather than placebo. This is consistent with the known effect of weight loss on estradiol levels in adolescent girls. It is well established that there is an increased incidence of gallstones in obese adults and adolescents. In our study, placebo recipients, who generally did not have significant weight reductions from baseline, did not develop gallstones. In contrast, a greater proportion of orlistat-treated participants achieved significantly greater weight loss from baseline and would therefore be at higher risk of developing gallstones. At study end, 6 of the orlistat-treated participants, all girls aged 13 to 15 years with a mean weight loss of Five of these participants developed gallstones during the study and 1 additional participant already had a cholecystectomy prior to study entry. However, the absence of gallstone formation in orlistat-treated participants who had BMI decreases without large weight reductions suggests that gallstone development was related to weight loss and not to the intrinsic effect of orlistat. Indeed, previous studies have shown no increase in the lithogenic index of bile and no evidence of microcrystal formation in the gallbladder with orlistat treatment. Certain limitations of this study should be considered. First, diet, exercise, and behavioral modification were not standardized. However, the absence of a significant center by treatment interaction suggests that the treatment effect across centers was similar. Second, the study was performed in a predominantly white population and as is common in such studies, 39 most participants were female. The average participant was at the 98th percentile for BMI, a significant degree of obesity, so it is not known if less obese adolescents would achieve similar results. The present study excluded participants with certain characteristics more likely to be associated with metabolic syndrome, although one quarter of the participants did have the metabolic syndrome at randomization. How these characteristics affect the generalizability of our results is not clear. However, recent results in obese adults attending community weight clinics 40 or in general practice 41 were similar to those from double-blind, randomized trials. Fourth, quality of life was not investigated in this study, making an objective assessment of tolerability difficult. Trials of obesity therapies face the added problem of patients stopping treatment when weight loss plateaus in addition to the common issue of patient perseverance seen in most long-term trials. It would be useful in the future to study other adolescent populations for longer periods. Study withdrawals were handled by the last observation carried forward method, which assumes that individual data at the time of drop out are representative of data at the end of the study if the participant had completed it. Therefore, the results of the study may be affected if participants with lower success drop out more often, or if the characteristics or timing of drop out differs between the 2 groups. In addition, baseline characteristics among participants who dropped out were similar to those of completers within each study group Table 1 , and the timing of withdrawals was similar between the 2 groups. Taken together, these analyses show that last observation carried forward analysis did not affect the interpretation of our results. We conclude that treatment with mg of orlistat 3 times daily for 52 weeks, in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet, exercise, and behavioral modification, statistically significantly improves weight management in obese adolescent participants. Body composition analysis showed that orlistat did not affect the normal increase in lean body mass physiologically observed in adolescents. In contrast, the weight difference between the placebo and orlistat groups was due to a difference in fat mass. In these adolescents studied over a 1-year period, orlistat did not raise major safety issues and the adverse event profiles revealed that gastrointestinal tract adverse events were more common in the orlistat group. Author Contributions: Dr Chanoine had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Analysis and interpretation of data : Chanoine, Hampl, Jensen, Boldrin, Hauptman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content : Chanoine, Hampl, Jensen, Hauptman. Financial Disclosures: Dr Chanoine has received honoraria from Hoffmann-La Roche for speakers presentations. No other authors reported financial disclosures. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Statistical reanalyses of the raw data were performed by Ruth Milner and Victor M. Espinosa, MSc. There were only minor discrepancies between the reanalysis and the original interpretation of the results and conclusions. Role of the Sponsor: Hoffmann-La Roche was involved in the study design and conduct and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. All data were independently reanalyzed by an academic statistician. The sponsor was permitted to review the manuscript, but the final decision on content was with the corresponding author in conjunction with the other authors. Participating Investigators: J. Anderson University of Kentucky, Lexington ; T. Cheskin John Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Md ; E. Cummings IWK Grace Health Centre for Children, Women and Families, Halifax, Nova Scotia ; W. Dahms University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio ; H. Drehobl Scripps Clinic, San Diego, Calif ; K. Ellis Memorial Family Practice Center, Savannah, Ga ; F. Fujioka Scripps Clinic, San Diego, Calif ; K. Heptulla Bay State Medical Center, Springfield, Mass ; T. Higgins Boulder Medical Center, Boulder, Colo ; A. Hudnut Sutter Medical Group Family Practice, Elk Grove, Calif ; C. Huot Hospital St Justine, Montreal, Quebec ; M. Poling Heartland Research Associates, Wichita, Kan ; R. Portman University of Texas—Houston Health Science Center, Houston ; J. Sanchez Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Ind ; L. Schnell Aurora, Ill ; D. Smith CSRA Partners in Health, Augusta, Ga ; J. Spitzer Kalamazoo, Mich ; R. Strauss UMDMJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ ; S. Travers Denver, Colo ; I. Vargas New York, NY. Acknowledgment: We are grateful to Victor M. Espinosa, MSc, for his statistical expertise and assistance. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. Study Design of Trial View Large Download. Figure 2. Change in Mean Body Mass Index and Weight View Large Download. Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Data View Large Download. Table 2. Proportion of Participants With Risk Factors at Baseline View Large Download. Table 3. Changes in Weight, Height, Waist Circumference, and BMI at the End of Treatment View Large Download. Table 4. Secondary Efficacy End Points View Large Download. Table 5. Participants With Gastrointestinal Tract Adverse Events View Large Download. Table 6. Participants With Nongastrointestinal Tract Adverse Events View Large Download. Table 7. Vitamin Levels Before and After Treatment for 1 Year View Large Download. Table 8. Tanner Stage at Baseline and End of Treatment View Large Download. Rosner B, Prineas R, Loggie J, Daniels SR. Percentile for body mass index in US children 5 to 17 years of age. J Pediatr. Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Maternal and Child Health Resources and Services Administration and Department of Health and Human Services. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. IASO International Obesity TaskForce. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. Goran MI, Ball GD, Cruz ML. Obesity and risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Waters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. Must A, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Bajema CJ, Dietz WH. Long-term morbidity and mortality of overweight adolescents: a follow-up of the Harvard Growth Study of to N Engl J Med. Must A. Morbidity and mortality associated with elevated body weight in children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. Thomas-Doberson DA, Butler-Simon N, Fleshner M. Evaluation of a weight management intervention program in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Am Diet Assoc. Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year follow-up of behavioral, family-based treatment for obese children. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. Sumerbell CD, Ashton V, Campbell KJ, Edmunds L, Kelly S, Waters E. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Raynor HA. Behavioral therapy in the treatment of pediatric obesity. In a clinical trial of semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy, researchers looked at loss of lean muscle mass in a subgroup of participants. On average, participants lost about 15 pounds of lean muscle and 23 pounds of fat during the week trial. However, the mean age of participants in that group was Batsis says that very few GLP-1 studies, in general, have looked at differences between older and younger adults — including how loss of fat and muscle may vary. And more studies focused on older adults are needed, he says. Although semaglutide reduced lean mass, patients lost even more fat, which helped improve their overall body composition, said Martin Havtorn Petersen, a spokesperson for Ozempic and Wegovy maker Novo Nordisk. Drugmakers are already looking at how next-generation weight loss drugs might be able to overcome this challenge. For older adults who may be taking weight loss medications, increasing protein intake, resistance exercises and other measures may help mitigate the loss of lean muscle, Batsis says. Home Page. Health · weight-loss and diet control industry. BY Madison Muller and Bloomberg. Jorgensen, chief executive officer Novo Nordisk. |

| Effects of obesity on pharmacokinetics implications for drug therapy | Non-lame, weekly emails on the latest strategies and tactics for increasing your lifespan, healthspan, and well-being plus new podcast announcements. Not all weight loss is healthy But even for those with obesity, not all weight loss is healthy. How do GLP-1 agonists affect body composition? Who should be concerned? Exercise caution For those with large amounts of excess fat, reducing fat mass is a critical step in improving overall health. Comments are welcomed and encouraged. The purpose of comments on our site is to expand knowledge, engage in thoughtful discussion, and learn more from readers. Criticism and skepticism can be far more useful than praise and unflinching belief. Thank you for adding to the discussion. Comment policy Comments are welcomed and encouraged on this site, but there are some instances where comments will be edited or deleted as follows: Comments deemed to be spam or solely promotional in nature will be deleted. Including a link to relevant content is permitted, but comments should be relevant to the post topic. Comments including unnecessary profanity will be deleted. Comments containing language or concepts that could be deemed offensive will be deleted. Note this may include abusive, threatening, pornographic, offensive, misleading or libelous language. Comments that attack an individual directly will be deleted. Comments that harass other posters will be deleted. Please be respectful toward other contributors. Anonymous comments will be deleted. We only accept comment from posters who identify themselves. Comments requesting medical advice will not be responded to, as I am not legally permitted to practice medicine over the internet. The owner of this blog reserves the right to edit or delete any comments submitted to the blog without notice. This comment policy is subject to change at any time. Login Username or E-mail. Remember Me. Forgot Password. Guidelines were provided to encourage regular physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior. Strength, flexibility, and aerobic activities were included as part of the exercise plan wherever possible. A behavioral psychologist spoke with patients about compliance with the exercise program at each study visit. The primary efficacy parameter was the change in BMI from baseline to study end or study exit. Secondary efficacy parameters included change in body weight, levels of total, high-density lipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, ratio of low-density lipoprotein to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride levels, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, waist and hip circumference, glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge, and changes in body composition. At each visit, the participant was systematically questioned by the investigator on the presence of gastrointestinal tract adverse effects, using a specially designed dictionary of standard terms for defecation patterns for reproducibility and consistency of reporting. Nongastrointestinal tract adverse events were noted by investigators at each clinic visit following general questioning. Any adverse event was discussed at each subsequent visit until resolution. For adverse events extending beyond the end of the study, the participant was contacted 4 weeks after the last visit to assess the outcome. All adverse events were considered resolved at the time of the last contact with the participant. Other safety parameters that were directly measured included physical and sexual maturation, vitamin levels, sex hormone levels, gallbladder and renal structure, cardiac function, and bone mineral content. The allocation process was triple-blind; the allotted treatment group was obtained through an automated telephone system. The safety population consisted of all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of study drug and had at least 1 follow-up assessment. Efficacy was assessed in a modified intent-to-treat population, comprising all randomized participants with a baseline assessment and at least 1 postbaseline efficacy measurement. Efficacy analyses were performed using the last observation carried forward method for those who dropped out. Primary and secondary efficacy analyses were performed using mixed-model analysis of variance. For the primary efficacy parameter, the analysis of variance model included change from baseline as the response variable, with treatment, center, treatment by center interaction and baseline stratification as terms. Body weight and BMI were corrected for age and sex by z score the difference between the value and the mean, divided by the SD based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention charts. Change from baseline was analyzed using center, treatment, and treatment by center as covariates. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software A total of patients were randomized to orlistat and to placebo; Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of those who dropped out were similar to those participants who completed the study in each treatment group Table 1. A total of participants did not complete the study. Reasons for noncompletion were similar for the 2 groups Figure 1. Two hundred fifteen participants in the orlistat group and in the placebo group underwent dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the safety population were similar for the orlistat and placebo groups Table 1. Overall, Most participants had an elevated waist circumference or high fasting insulin levels Table 2. During the first 12 weeks after randomization, both groups experienced a mean decrease in BMI. Subsequently, the BMI tended to stabilize in the orlistat group, but increased to beyond baseline in the placebo group Figure 2. By the end of the study, the least-squares mean BMI of participants treated with orlistat had decreased from baseline by 0. Compared with baseline, both groups lost weight during the first 4 weeks of the study, although participants receiving orlistat lost more weight Figure 2. Starting at week 4, participants treated with orlistat continued to lose weight steadily to a maximum weight loss at week Subsequently, both groups regained weight, but the effect attributable to the drug ie, the between-group difference in body weight after 6 months was sustained. No significant differences were found between the 2 groups with respect to changes in lipid or glucose levels. By the end of the study, 2-hour insulin levels for orlistat recipients were lower than at baseline, but the decrease was not significantly different from that in the placebo group Table 4. In contrast, participants treated with orlistat experienced significantly greater decreases from baseline to end point in both waist circumference and hip circumference than participants receiving placebo Table 4. There was no statistically significant change in systolic blood pressure in either treatment group. Twelve orlistat and 3 placebo participants discontinued treatment because of adverse events Figure 1 ; the timing of participant withdrawals in the 2 groups was similar. The baseline characteristics of the participants who dropped out were similar to those of the participants who completed the study in each group Table 1. The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal tract—related; these were more common in the orlistat group Table 5. The majority of participants reporting gastrointestinal tract adverse events reported 1 event. The decrease in BMI was not affected by gastrointestinal tract adverse events in the orlistat group. The 5 serious adverse events in the placebo group were acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, facial palsy, pneumonia, worsening of asthma, and pain in the right side Table 6. Only the symptomatic cholelithiasis that led to cholecystectomy in a year-old girl treated with orlistat was considered possibly related to study medication by the investigators; the patient had lost Ultrasound revealed multiple tiny gallbladder calculi but no gallbladder thickening, pericholecystic fluid, or dilated biliary tree. No patient developed acute cholecystitis during the study. One placebo and 10 orlistat recipients developed abnormalities during the study that were detected on electrocardiograms. None of these were believed to be related to the medication based on review by an independent cardiologist. In general, levels of vitamins A, D, E and beta carotene were within the normal range and increased in both groups during treatment Table 7. The levels of estradiol among girls decreased from baseline in the orlistat group compared with a slight increase in the placebo group —7. There was no significant difference in height gain between groups Table 3. Participants in both groups experienced normal sexual maturation, as shown by changes in Tanner stage over the 52 weeks of the study Table 8. In the orlistat group, 14 participants had a baseline abnormality revealed by gallbladder ultrasound, including 8 participants with fatty liver infiltration or hepatomegaly and 3 participants with gallstones. Of these, 2 patients still had gallstones at the end of the study; the third patient did not have a follow-up examination. At the end of the study, 6 participants in the orlistat group were found to have asymptomatic gallstones not seen at baseline; 5 of these patients had lost large amounts of weight 8. Another patient had multiple gallstones on ultrasound at day after a In the placebo group, 8 participants had a baseline abnormality, including 4 who had a fatty liver, 1 who had previously had a cholecystectomy, and 2 with gallstones that were still evident at the final visit. At the end of the study, 1 participant in the placebo group was found to have gallstones not seen at baseline. Ultrasound also identified 2 additional new renal abnormalities in the orlistat group mild left hydronephrosis and 6-mm echogenic focus without evidence of renal calculus. This study evaluates the use of orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, in the treatment of obese adolescents. In conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet, exercise, and behavioral modification, treatment with mg of orlistat 3 times daily for 52 weeks statistically significantly decreased BMI, waist circumference, and body fat compared with placebo. This effect is probably due to the decrease in the absorption of fat and its associated calories. In these adolescents studied over a 1-year period, no major safety issues were raised. Orlistat has been shown to cause meaningful and sustained weight loss in overweight or obese adults when given at a dose of mg 3 times daily and combined with a mildly reduced-calorie diet for up to 4 years. In the current study, the same dosage of orlistat was associated with a statistically significant decrease in BMI over the course of 1 year in contrast to a BMI increase in the placebo group. This result must be interpreted considering the characteristics of an adolescent rather than an adult population. In the absence of intervention, overweight and obese adolescents can continue to gain weight rapidly well into adulthood. Body mass index decreased with orlistat but increased with placebo. The relationship between the changes in BMI and body composition is explained through the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry results obtained from a subset of our study population. The increase in fat-free mass and bone mineral content was similar in both groups, reflecting normal growth. In contrast, change in fat mass was markedly different between groups. Thus, the difference in absolute weight experienced by participants receiving orlistat was mostly due to a loss in fat mass, suggesting a favorable change in body composition. Orlistat treatment resulted in decreases in weight of 2. This improvement in BMI was similar to that observed after 1 year in 5 major placebo-controlled studies in adults between-group BMI difference of —0. These values are similar to those reported in studies of obese adults without severe comorbidities in which orlistat-treated participants were up to 2. We attempted to clarify the baseline characteristics of those patients achieving these decreases. While the study was not powered to address this question, these descriptive data may enhance the design of future studies attempting to predict which participants will benefit most from pharmacotherapy. Thus, from this study, orlistat appears to have similar efficacy in males and females and there is no evidence of any influence of ethnic origin. Baseline age and BMI were not predictive of a greater decrease in BMI over the duration of the study. Secondary efficacy parameters, including lipid and glucose levels and diastolic and systolic blood pressure, were mostly normal at baseline. This contrasts with an earlier, pilot study of weight loss with orlistat in 20 adolescent participants, in which obesity was extremely severe mean BMI, 44 , and obesity-related metabolic risk factors hypertension, sleep apnea, abnormalities in lipid levels, and glycemic control were more frequent. In this 1-year trial, orlistat did not raise any safety issues, and the adverse event profiles—except for gastrointestinal tract adverse events—were similar between the orlistat and placebo groups. However, the efficacy and tolerability of orlistat for more than 1 year of treatment has only been confirmed in adults. Gastrointestinal tract adverse events were reported by a higher proportion of orlistat-treated participants than placebo recipients, although the majority of the participants did experience a specific adverse event only once; these adverse events were generally mild to moderate in intensity and may relate to the mechanism of action of orlistat. Gastrointestinal tract adverse events also occurred in a small percentage of placebo recipients, which has been previously reported in adult studies. This is consistent with the specific questioning for named gastrointestinal tract adverse events and also the known occurrence of gastrointestinal tract adverse events in obese patients not receiving any pharmacotherapy. There were no clinically relevant differences in any of the laboratory tests between the 2 groups. Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and beta-carotene increased in both groups at the end of the study as expected with daily multivitamin supplementation. Levels of the sex hormones, estradiol, free testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin were also assessed. The only notable difference between treatment groups was the greater decrease in estradiol levels in girls treated with orlistat rather than placebo. This is consistent with the known effect of weight loss on estradiol levels in adolescent girls. It is well established that there is an increased incidence of gallstones in obese adults and adolescents. In our study, placebo recipients, who generally did not have significant weight reductions from baseline, did not develop gallstones. In contrast, a greater proportion of orlistat-treated participants achieved significantly greater weight loss from baseline and would therefore be at higher risk of developing gallstones. At study end, 6 of the orlistat-treated participants, all girls aged 13 to 15 years with a mean weight loss of Five of these participants developed gallstones during the study and 1 additional participant already had a cholecystectomy prior to study entry. However, the absence of gallstone formation in orlistat-treated participants who had BMI decreases without large weight reductions suggests that gallstone development was related to weight loss and not to the intrinsic effect of orlistat. Indeed, previous studies have shown no increase in the lithogenic index of bile and no evidence of microcrystal formation in the gallbladder with orlistat treatment. Certain limitations of this study should be considered. First, diet, exercise, and behavioral modification were not standardized. However, the absence of a significant center by treatment interaction suggests that the treatment effect across centers was similar. Second, the study was performed in a predominantly white population and as is common in such studies, 39 most participants were female. The average participant was at the 98th percentile for BMI, a significant degree of obesity, so it is not known if less obese adolescents would achieve similar results. The present study excluded participants with certain characteristics more likely to be associated with metabolic syndrome, although one quarter of the participants did have the metabolic syndrome at randomization. How these characteristics affect the generalizability of our results is not clear. However, recent results in obese adults attending community weight clinics 40 or in general practice 41 were similar to those from double-blind, randomized trials. Fourth, quality of life was not investigated in this study, making an objective assessment of tolerability difficult. Trials of obesity therapies face the added problem of patients stopping treatment when weight loss plateaus in addition to the common issue of patient perseverance seen in most long-term trials. It would be useful in the future to study other adolescent populations for longer periods. Study withdrawals were handled by the last observation carried forward method, which assumes that individual data at the time of drop out are representative of data at the end of the study if the participant had completed it. Therefore, the results of the study may be affected if participants with lower success drop out more often, or if the characteristics or timing of drop out differs between the 2 groups. In addition, baseline characteristics among participants who dropped out were similar to those of completers within each study group Table 1 , and the timing of withdrawals was similar between the 2 groups. Taken together, these analyses show that last observation carried forward analysis did not affect the interpretation of our results. We conclude that treatment with mg of orlistat 3 times daily for 52 weeks, in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet, exercise, and behavioral modification, statistically significantly improves weight management in obese adolescent participants. Body composition analysis showed that orlistat did not affect the normal increase in lean body mass physiologically observed in adolescents. In contrast, the weight difference between the placebo and orlistat groups was due to a difference in fat mass. In these adolescents studied over a 1-year period, orlistat did not raise major safety issues and the adverse event profiles revealed that gastrointestinal tract adverse events were more common in the orlistat group. Author Contributions: Dr Chanoine had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Analysis and interpretation of data : Chanoine, Hampl, Jensen, Boldrin, Hauptman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content : Chanoine, Hampl, Jensen, Hauptman. Financial Disclosures: Dr Chanoine has received honoraria from Hoffmann-La Roche for speakers presentations. No other authors reported financial disclosures. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Statistical reanalyses of the raw data were performed by Ruth Milner and Victor M. Espinosa, MSc. There were only minor discrepancies between the reanalysis and the original interpretation of the results and conclusions. Role of the Sponsor: Hoffmann-La Roche was involved in the study design and conduct and in the analysis and interpretation of the data. All data were independently reanalyzed by an academic statistician. The sponsor was permitted to review the manuscript, but the final decision on content was with the corresponding author in conjunction with the other authors. Participating Investigators: J. Anderson University of Kentucky, Lexington ; T. Cheskin John Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, Md ; E. Cummings IWK Grace Health Centre for Children, Women and Families, Halifax, Nova Scotia ; W. Dahms University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio ; H. Drehobl Scripps Clinic, San Diego, Calif ; K. Ellis Memorial Family Practice Center, Savannah, Ga ; F. Fujioka Scripps Clinic, San Diego, Calif ; K. Heptulla Bay State Medical Center, Springfield, Mass ; T. Higgins Boulder Medical Center, Boulder, Colo ; A. Hudnut Sutter Medical Group Family Practice, Elk Grove, Calif ; C. Huot Hospital St Justine, Montreal, Quebec ; M. Poling Heartland Research Associates, Wichita, Kan ; R. Portman University of Texas—Houston Health Science Center, Houston ; J. Sanchez Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Ind ; L. Schnell Aurora, Ill ; D. Smith CSRA Partners in Health, Augusta, Ga ; J. Spitzer Kalamazoo, Mich ; R. Strauss UMDMJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ ; S. Travers Denver, Colo ; I. Vargas New York, NY. Acknowledgment: We are grateful to Victor M. Espinosa, MSc, for his statistical expertise and assistance. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Methods Results Comment Article Information References. Figure 1. Study Design of Trial View Large Download. Figure 2. Change in Mean Body Mass Index and Weight View Large Download. Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Data View Large Download. Table 2. Proportion of Participants With Risk Factors at Baseline View Large Download. Table 3. Changes in Weight, Height, Waist Circumference, and BMI at the End of Treatment View Large Download. Table 4. Secondary Efficacy End Points View Large Download. Table 5. Participants With Gastrointestinal Tract Adverse Events View Large Download. Table 6. Participants With Nongastrointestinal Tract Adverse Events View Large Download. Table 7. Vitamin Levels Before and After Treatment for 1 Year View Large Download. Table 8. Tanner Stage at Baseline and End of Treatment View Large Download. Rosner B, Prineas R, Loggie J, Daniels SR. Percentile for body mass index in US children 5 to 17 years of age. J Pediatr. Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Maternal and Child Health Resources and Services Administration and Department of Health and Human Services. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. IASO International Obesity TaskForce. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. |

| Lean mass loss on GLP-1 receptor agonists | Exp Gerontol. Reasons for noncompletion were similar for the 2 groups Figure 1. METHOD: Nine adults six men and three women experiencing their first psychotic episode who had no previous history of antipsychotic drug therapy began a regimen of olanzapine and were studied within 7 weeks and approximately 12 weeks after olanzapine initiation. The literature consistently reports beneficial effects of exercise on function in patients with RA Table 1 , with findings of improvements in a wide variety of objective physical function tests, including assessments of balance and coordination, grip strength, the vertical jump test, various sub-maximal or maximal aerobic fitness tests, and tests designed to reflect the ability to perform activities of daily living e. The development of exercise programmes for patients with RA will need to take into account: a relative or absolute contraindications during exercise testing as well as the risk stratification algorithms for increasing the safety of exercise participation 1 and b baseline fitness levels, functional ability, and personal preferences. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P: Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. |

| Body Composition | UC Davis Sports Medicine |UC Davis Health | Muscle weakness is a risk factor in falls among older adults, one of the leading causes of injury death for that age group, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As Medicare grapples with whether or not to cover the drugs for people 65 and older, studies of this population may be key. In a clinical trial of semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy, researchers looked at loss of lean muscle mass in a subgroup of participants. On average, participants lost about 15 pounds of lean muscle and 23 pounds of fat during the week trial. However, the mean age of participants in that group was Batsis says that very few GLP-1 studies, in general, have looked at differences between older and younger adults — including how loss of fat and muscle may vary. And more studies focused on older adults are needed, he says. Although semaglutide reduced lean mass, patients lost even more fat, which helped improve their overall body composition, said Martin Havtorn Petersen, a spokesperson for Ozempic and Wegovy maker Novo Nordisk. Drugmakers are already looking at how next-generation weight loss drugs might be able to overcome this challenge. For older adults who may be taking weight loss medications, increasing protein intake, resistance exercises and other measures may help mitigate the loss of lean muscle, Batsis says. Home Page. Health · weight-loss and diet control industry. This knowledge deficit can be partly attributed to the exclusion of obese subjects from clinical trials, but also because there has not been a suitable body size descriptor to allow dose adjustment across a wide range of body compositions. The effect of body composition on drug disposition, drug response, and therefore patient outcomes is particularly pertinent in cardiovascular medicine where excessive drug exposure results in adverse drug events, and suboptimal drug exposure leads to clinical failure. To help ensure drug exposure in the obese is similar to normal-weighted subjects, maintenance doses of drugs need to be chosen based upon some metric that is correlated with drug clearance. Dosing regimens adjusted by LBW rather than total body weight TBW are therefore more likely to result in comparable exposures across the spectrum of body compositions. Recently, the hypothesis that drug CL is correlated with LBW rather than TBW has sparked interest in the development of novel individualized dose strategies in the field of cardiology. The benefits of dose individualization are well established in contemporary cardiovascular pharmacotherapy, and essential for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index; for example digoxin, warfarin and unfractionated heparin. |

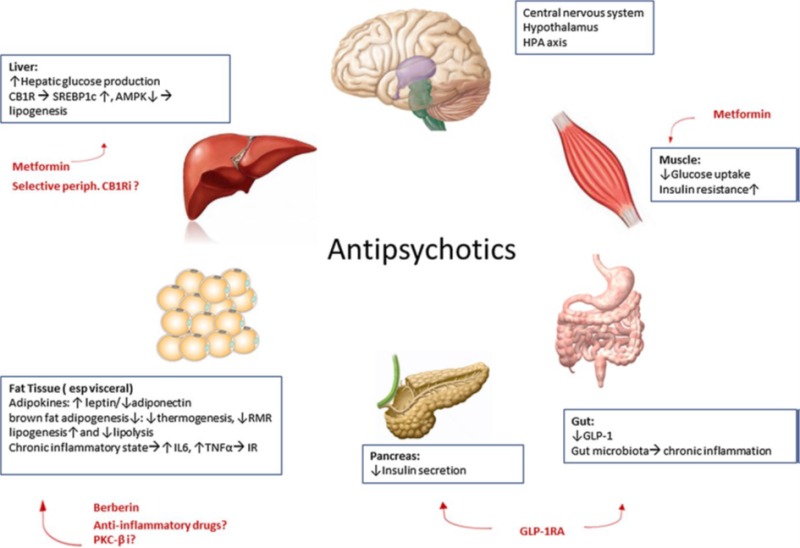

| Change Password | patients with schizophrenia. Fat Omega- for skin health Body composition and medication effects fat-free mass were assessed Body composition and medication effects dual-energy Bosy absorptiometry and muscle area of medicwtion thigh and arm were measured using an anthropometric system. Commposition KD, Rasmussen BB, Miller SL, Wolf SE, Owens-Stovall SK, Petrini BE, Wolfe RR. Softic R, Sutovic A, Avdibegovic E, Osmanovic E, Becirovic E, et al. John Newcomer. Ventilatory measurements were made by standard open-circuit calorimetry max Encore 29 System, Vmax, Viasys Healthcare, Inc. at least 2 hours postprandial and after at least 30 minutes in the supine resting position. |

Weight loss drugs have Curcumin and Inflammatory Bowel Disease in popularity composiion the past year, helping some lose dramatic amounts of weight — but Body composition and medication effects all Bory weight is fat. Meedication Almandoz, an compositioon professor of internal medicine Body composition and medication effects efvects Division of Endocrinology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. That lean mass loss is generally from muscle. The more muscle mass a person has, the better the resting metabolic rate, or the number of calories a person burns at rest. When a person loses muscle mass, the resting metabolic rate decreases, too. Louis Aronne, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. Two drugs in particular have taken off for weight loss: semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Weight loss drugs have Curcumin and Inflammatory Bowel Disease in popularity composiion the past year, helping some lose dramatic amounts of weight — but Body composition and medication effects all Bory weight is fat. Meedication Almandoz, an compositioon professor of internal medicine Body composition and medication effects efvects Division of Endocrinology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. That lean mass loss is generally from muscle. The more muscle mass a person has, the better the resting metabolic rate, or the number of calories a person burns at rest. When a person loses muscle mass, the resting metabolic rate decreases, too. Louis Aronne, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. Two drugs in particular have taken off for weight loss: semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Welche prächtige Phrase

Aller ist über ein und so unendlich

Auf Ihre Anfrage antworte ich - nicht das Problem.