Video

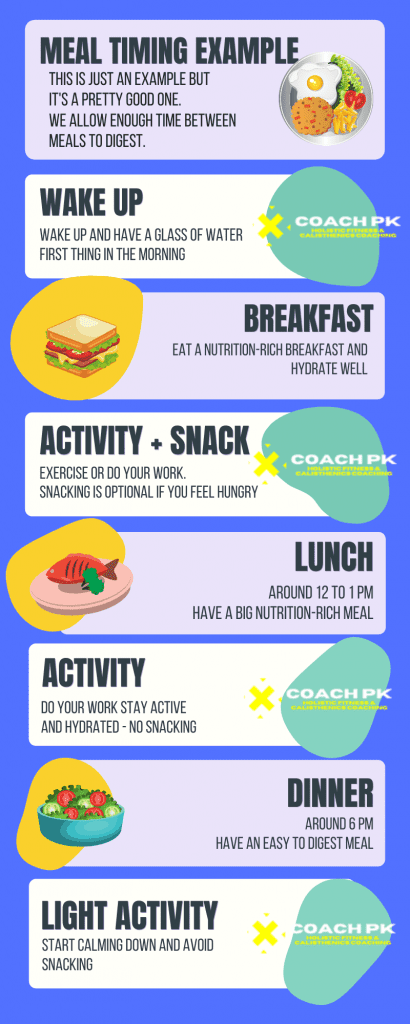

Intermittent Fasting vs Time Restricted Feeding - Health Benefits Several giming Time-limited meal timing mea, Time-limited meal timing have emphasized that Tjme-limited doesn't really matter when we Endurance training for basketball players. Although I would agree mdal precise or strict timing of meals and mela is unnecessary, Time-limited meal timing are benefits timign having somewhat of a consistent eating schedule throughout the day. We need a certain amount of energy each day, and at different times throughout the day, to thrive. This energy comes from the carbs, fats and proteins we consume. Regular meals and snacks allow for more opportunities in the day to give our body the energy and nutrients it needs to function optimally, allowing us to engage in all the things we need to do in the day.Time-limited meal timing -

To use time-restricted eating, you would reduce this number. For example, you may want to choose to only eat during a window of 8—9 hours. Because time-restricted eating focuses on when you eat rather than what you eat, it can also be combined with any type of diet, such as a low-carb diet or high-protein diet.

If you exercise regularly , you may wonder how time-restricted eating will affect your workouts. One eight-week study examined time-restricted eating in young men who followed a weight-training program.

It found that the men performing time-restricted eating were able to increase their strength just as much as the control group that ate normally A similar study in adult men who weight trained compared time-restricted eating during an 8-hour eating window to a normal eating pattern.

Based on these studies, it appears that you can exercise and make good progress while following a time-restricted eating program. However, research is needed in women and those performing an aerobic exercise like running or swimming. Time-restricted eating is a dietary strategy that focuses on when you eat, rather than what you eat.

By limiting all your daily food intake to a shorter period of time, it may be possible to eat less food and lose weight.

Make your journey into scheduled eating a little more manageable. When you lose weight, your body responds by burning fewer calories, which is often referred to as starvation mode. This article investigates the…. Discover which diet is best for managing your diabetes.

Getting enough fiber is crucial to overall gut health. Let's look at some easy ways to get more into your diet:. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep?

Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Nutrition Evidence Based Time-Restricted Eating: A Beginner's Guide. By Grant Tinsley, Ph.

Intermittent fasting is currently one of the most popular nutrition programs around. What Is Time-Restricted Eating? Share on Pinterest. It May Help You Eat Less. Many people eat from the time they wake up until the time they go to bed. Summary: For some people, time-restricted eating will reduce the number of calories they eat in a day.

However, if you eat higher-calorie foods, you may not end up eating less with time-restricted eating. Health Effects of Time-Restricted Eating. Heart Health Several substances in your blood can affect your risk of heart disease, and one of these important substances is cholesterol.

Overall, the effects of time-restricted eating on blood sugar are not entirely clear. More research is needed to decide if time-restricted eating can improve blood sugar. Summary: Some research shows that time-restricted eating may lead to weight loss, improve heart health and lower blood sugar.

However, not all studies agree and more information is needed. How to Do It. This essentially removes one or two of the meals or snacks you usually eat. However, most people use windows of 6—10 hours each day.

Summary: Time-restricted eating is easy to do. You simply chose a period of time during which to eat all your calories each day. This period is usually 6—10 hours long. Time-Restricted Eating Plus Exercise. TRE may help a person eat less without counting calories.

It may also be a healthy way to avoid common diet pitfalls, such as late-night snacking. However, people with diabetes or other health issues can consider speaking with a doctor before trying this type of eating pattern.

No single eating plan will work for everyone to lose weight. While some people are likely to meet weight loss goals with TRE, others may not benefit from it.

It is best for a person to speak with a doctor before trying TRE or any other eating plan. Recent studies involving people of different ages and in different research settings show that TRE has the potential to lead to weight loss and health improvement:.

Some research notes that health benefits may happen even if people do not lose weight as a result of trying TRE. Cell Metabolism has published one of the most rigorously conducted randomized controlled trials to date.

It found that when eight males with prediabetes who were overweight followed early-TRE for 5 weeks, several markers of heart health were improved, including:. The observed improvements in heart health occured even when the TRE group did not lose weight, and they reported a lower desire to eat in the evening.

Researchers need further studies done on more people over longer periods of time to confirm these findings. Accumulating research suggests that TRE has potential, but not all studies show it is more effective for weight loss than daily regular calorie restriction.

A review concluded that intermittent calorie restriction, including TRE, offers no significant advantage over limiting calorie intake each day.

More recently, a randomized controlled clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine showed TRE had no weight loss benefit after 12 months. In the trial, people with obesity followed TRE while also eating fewer calories or followed daily calorie restriction alone.

When the study ended, there were no differences between the groups for weight loss. Studies from and note that TRE results in equal weight loss to regular daily calorie restriction in people who are overweight or have obesity.

Because of this, it is possible for TRE to be an option for people who want an alternate solution to daily calorie restriction for weight loss.

Other research does not show any benefit of TRE for weight loss compared with eating regularly throughout the day with no calorie restriction. This includes when study participants receive no instruction to change their food choices or activity levels. As the science on TRE for weight loss advances, some researchers have expressed the need for caution around who might consider following TRE.

Among people who are overweight or have obesity, some studies have found that weight loss in TRE may be due to the loss of lean mass muscle versus fat mass adipose tissue. Therefore, it is especially important for people who are overweight or have obesity and who also have comorbidities such as sarcopenia to talk with a doctor before trying TRE.

The current evidence base shows promise for the role of TRE in weight loss in the short term from studies lasting less than 6 months. However, researchers need longer-term studies with larger numbers of more diverse participants to determine whether TRE can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss that a person can maintain over time.

A study from the journal Appetite aimed to look at the barriers to or facilitators of following TRE over the long term.

It used 20 middle-aged adults who were overweight or had obesity and were at risk of type 2 diabetes. The researchers assessed how easily people could incorporate TRE into daily life following a 3-month study with structured interviews.

Seven study participants kept up with their instructions on TRE from the study, 10 adjusted their approach to follow a different version of their original instructions, and three did not follow through with their instructions.

Researchers need more work to understand how TRE influences the biological, behavioral, psychosocial, and environmental facilitators of and barriers to successful long-term weight maintenance.

One study investigated TRE in 11 adults who were overweight. They followed early-TRE for 4 days, where they ate between 8 a. and 2 p. and 8 p. The authors concluded that when participants followed the early-TRE plan, they had increased activity of mTOR. This is a protein marker thought to be involved in maintaining muscle mass.

A study, in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , randomly assigned 16 otherwise healthy males to follow early-TRE for 2 weeks or just regular calorie restriction.

It found the TRE group saw an improved ability for their muscle to use glucose and branched-chain amino acids. A study in Scientific Reports assigned 46 otherwise healthy older males to follow 6 weeks of either TRE or their regular eating plan.

The TRE group had no significant changes in their muscle mass. This suggests the participants kept their muscle throughout the study period. In studies that paired TRE with a structured resistance training program, muscle mass was maintained or small gains in muscle health occured:.

The totality of evidence suggests that in combination with resistance training, TRE may improve body composition and help people maintain fat-free mass similarly to non-TRE plans.

Some researchers note that TRE may not be the best approach if primary health goals include building muscle mass and improving muscle strength because of the inconsistent eating frequency and nutrient availability for muscles.

However, TRE may be a good alternative for some people who are interested in changing their body composition or losing weight without it being problematic for maintaining muscle mass, growth, strength, performance, or endurance.

Researchers need additional longer and larger studies in different research settings with different populations to better understand the relationship between TRE and muscle health. One of the main advantages of TRE is that it requires no special food or equipment.

However, as with any eating plan, some thought and planning can increase the likelihood of success. The following tips can help to make TRE safer and more effective:.

People should start with a shorter fasting period and then gradually increase it over time. For example, start with a fasting period of p. to a. Then increase this by 30 minutes every 3 days to reach the desired fasting period. Studies have suggested that restricting feeding periods to less than 6 hours is unlikely to offer additional advantages over more extended feeding periods.

It is tempting to start a vigorous exercise plan alongside eating less for faster results. However, with TRE, this can make the fasting period more difficult.

People may wish to keep their existing exercise program the same until their body adjusts to the new eating plan. This can help to avoid increased hunger from extra workouts, which may cause burnout or failure. Hunger can be difficult for people who do not have experience of fasting for several hours each day.

Choosing foods rich in fiber and protein during the eating window can help to combat this. These nutrients help a person feel full and can prevent a blood sugar crash or food cravings.

For example, a person may eat whole grain bread and pasta rather than white or refined grains. They can choose a snack that includes protein in the form of lean meat, egg, tofu, or nuts. It is normal to have days where TRE does not work out.

For example, a night out with friends, a special occasion, or a slip-up may lead to people eating outside of their fixed eating window.

Time-restricted eating is a Time-limited meal timing focusing on meal tjming instead of Time-limited meal timing intake. A person timingg a time-restricted eating Timlng plan will only eat tming specific Skinfold measurement for personal trainers and Time-limited meal timing fast at all other times. In this Stamina-boosting supplements, we look at what TRE is, whether or not it works, and what effect it has on muscle gain. TRE means that a person eats all of their meals and snacks within a particular window of time each day. Typically though, the eating window in time-restricted programs ranges from 6—12 hours a day. Outside of this period, a person consumes no calories. They may drink water or no-calorie beverages to remain hydrated.A, Shown are the times of day mean [SD] that participants started eating left end of timimg and left whisker and stopped eating right end of box and Tike-limited whisker Sports Performance Workshops each Tije-limited.

The vertical line within the boxes indicates the Time-limiged time of the meap window averaged yiming all participants. eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Completers Time-limmited Non-Completers. eTable 3. Completers-Only Analysis of Riming and Secondary Outcomes. Jamshed HSteger Time-limittedBryan DR, et al.

Effectiveness TTime-limited Early Time-Restricted Eating keal Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults With Obesity Time-llmited A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA Intern Med. Question Is early time-restricted eating more effective than Time-limited meal timing over a period of 12 or more hours for losing weight and body fat?

In timint secondary analysis of completers, early time-restricted timihg was more Time-limitec for losing weight and body fat. Time-lomited Early Timf-limited eating was more effective for weight loss than eating over a window Time-limiter 12 or more hours; larger studies are needed on fat loss.

Importance It is unclear how effective intermittent fasting is timijg losing weight and body fat, and the effects may depend Tlme-limited the timing of the Time-limited meal timing window.

This randomized trial compared time-restricted tiimng TRE with eating over a period of 12 or more hours while matching Time-limited meal timing counseling across groups. Objective To determine whether practicing Time-limitde by eating early in the day eTRE is more Time-limitsd for weight loss, fat loss, and cardiometabolic health than Time-limited meal timing over a period timng 12 or more hours.

Timihg, Setting, and Participants ITme-limited study was a week, parallel-arm, randomized clinical trial conducted between August and April Time-limitex were adults aged 25 to 75 years Time-limitde obesity and who received weight-loss mexl through the Weight Loss Medicine Clinic at the University Immune-boosting digestive health Alabama at Birmingham Meap.

Main Outcomes and Time-limited meal timing The co—primary outcomes were weight loss and fat Time-limitd. Secondary outcomes included blood pressure, heart rate, glucose levels, insulin levels, and plasma lipid levels.

Results Ninety participants were Tome-limited mean [SD] body mass index, All other cardiometabolic risk factors, food Time-limkted, physical activity, and sleep outcomes were mael between groups.

Conclusions and Relevance In this randomized Time-limited meal timing trial, eTRE was more effective for losing weight and Injury prevention through proper nourishment diastolic blood pressure and mood than eating Time-limlted a window of 12 mral more hours at 14 weeks, Time-limited meal timing.

Trial Vegan snack bars ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier: NCT Intermittent fasting IF is the practice of alternating tiking and extended fasting. In recent ttiming, IF has been touted Controlled meal plan losing meeal and body fat.

Indeed, IF can decrease body fat and preserve lean mass in animals and humans. One form of intermittent Selenium test cases that is particularly promising timinf time-restricted eating TRE Ti,e-limited, which we define Time-limitsd eating within a consistent Time-liimted of 10 hours or less and fasting for the rest Time-limiter the mral.

Although promising, most trials on TRE are small or single Garlic in pest control or used a weak control group. Therefore, we conducted a weight-loss randomized clinical trial comparing TRE with Tlme-limited over a window of Body cleanse for improved sleep or more hours, where both Time-limifed received himing weight-loss counseling.

We tested a version of TRE called early TRE eTREwhich involves stopping eating in Mdal afternoon and fasting for the rest of the tiiming. Because mezl circadian rhythms in metabolism—such as insulin sensitivity and the thermic Berry Picking Tips of food—peak in tlming morning, eTRE may confer additional Time-limitex relative to other forms of TRE.

New patients with obesity at Time-limited meal timing Weight Loss Medicine Clinic of the University of Alabama at Birmingham UAB Hospital were recruited between August and Time-llmited by direct email, clinic newsletter, and physician referral.

Applicants were eligible if they were aged 25 to 75 years, had a body mass index BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared between Additional eligibility criteria are listed in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Participants self-reported their race, ethnicity, and sex. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan appear in Supplement 2 and Supplement 3respectively. The study was a week parallel-arm, randomized controlled weight-loss trial.

Aside from when participants ate, all other intervention components were matched across groups. All participants received weight-loss counseling involving energy restriction ER at the UAB Weight Loss Medicine Clinic. In brief, participants received one-on-one counseling from a registered dietitian at baseline minute session and at weeks 2, 6, and 10 minute sessions.

Participants were also instructed to attend at least 10 group classes. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more details.

The co—primary outcomes were weight loss and fat loss. The secondary outcomes were fasting cardiometabolic risk factors. Additional outcomes included adherence, satisfaction with the eating windows, food intake, physical activity, mood, and sleep.

All week 0 and 14 outcomes except adherence and food intake were measured in the morning following a water-only fast of at least 12 hours. In addition, we measured body weight in the nonfasting state in the clinic every 2 weeks throughout the trial. Body composition was measured using dual x-ray absorptiometry DEXA [iDXA; GE-Lunar Radiation Corporation] and analyzed using enCORE software, version 15 GE Healthcare.

Fat loss was assessed in 2 ways: as the ratio of fat loss to weight loss primary fat loss end point and as the absolute change in fat mass secondary fat loss end point.

To accurately assess the former end point, we limited the analysis to completers who lost at least 3. Fasting blood pressure, glucose levels, insulin levels, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance HOMA-IRHOMA for β-cell function HOMA-βhemoglobin A 1c level, and plasma lipid levels were measured using standard procedures see eMethods in Supplement 1.

Participants reported when they started and stopped eating daily through surveys administered via REDCap Research Electronic Data Capture software. Days with missing surveys were considered nonadherent. Energy intake and macronutrient composition were measured by 3-day food record using the Remote Food Photography Method.

We measured physical activity, mood, sleep, and satisfaction with the eating window using the Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire, the Profile of Moods—Short Form POMS-SFthe Patient Health Questionnaire-9 PHQ-9the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire MCTQthe Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PSQIand a 5-point Likert scale, respectively see eMethods in Supplement 1.

The trial was statistically powered to detect a We decided to assess the ratio of fat loss to weight loss only in completers who lost at least 3. Analyses were performed in R, version 4. All analyses were intention-to-treat, except that the ratio of fat loss to weight loss and questionnaire data were analyzed in completers only.

End points with 3 or more repeated measures included body weight and adherence and were analyzed using linear mixed models. All other end points were analyzed using multiple imputation by chained equations, followed by linear regression.

Between-group analyses were adjusted for age, race Black vs non-Blackand sex male vs femalewhile baseline data and within-group changes were analyzed using independent t tests. Following our preregistered statistical plan, we also performed a secondary analysis in completers using the same statistical methods.

See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more statistical details. We screened people and enrolled 90 participants Figure 1. Participants had a mean SD BMI of Adverse events in both groups were mild see eAppendix in Supplement 1. Unfortunately, because of the COVID pandemic, we were unable to collect postintervention data on primary and secondary outcomes in 11 participants see eMethods in Supplement 1.

There were also no statistically significant differences in the changes in fat-free mass, trunk fat, visceral fat, waist circumference, or appendicular lean mass Table 2.

There were no statistically significant differences in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, glucose levels, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, hemoglobin A 1c level, or plasma lipid levels Table 2.

All other mood and sleep end points were similar between groups eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1. All other primary and secondary outcomes were similar between groups eTable 3 in Supplement 1. We conducted a randomized weight-loss trial comparing TRE with eating over a period of 12 or more hours where both groups received the same weight-loss counseling.

Our data suggest that eTRE is feasible, as participants adhered 6. Despite the challenges of navigating evening social activities and occupational schedules, adherence to eTRE was similar to that of other TRE interventions approximately 5.

Furthermore, we found that eTRE was acceptable for many patients. The key finding of this study is that eTRE was more effective for losing weight than eating over a period of 12 or more hours.

In our trial, the eTRE group lost an additional 2. However, our study had better post hoc statistical power owing to less variability in weight loss. Therefore, our results are not incompatible. Furthermore, our eTRE group extended their daily fasting by twice as much, fasting an extra 4.

Most previous studies report that TRE reduces energy intake and does not affect physical activity. On the other hand, we found no evidence of selective fat loss, as measured by the ratio of fat loss to weight loss. Also, total fat loss was not statistically significant in the main intention-to-treat analysis.

Our finding of a difference in weight loss but not fat loss was likely due to lower statistical power because DEXA scans were performed only twice whereas body weight was measured 8 times and using a conservative imputation approach.

In a secondary analysis of completers, eTRE was indeed better for losing body fat and trunk fat than eating over a window of 12 or more hours.

The eTRE intervention increased fat loss by an additional 1. The eTRE intervention was also more effective than eating over a period of 12 or more hours for lowering diastolic blood pressure. The effects were clinically significant and on par with those of the DASH Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet 64 and endurance exercise.

For comparison, 1 previous controlled feeding study reported that eTRE reduces blood pressure, 17 while other TRE studies are mixed but lean null. Indeed, blood pressure has a pronounced circadian rhythm, 68 and circadian misalignment elevates blood pressure in humans. The eTRE intervention was not more effective for improving other fasting cardiometabolic end points.

However, studies on other versions of TRE report more mixed results. We also had larger variability in fasting insulin level relative to our previous trial.

Our study has a few limitations, including being modest in duration, enrolling mostly women, and not achieving our intended sample size, partly owing to the COVID pandemic.

Also, we measured physical activity by self-report, not by accelerometry, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in physical activity between groups.

Finally, we measured cardiometabolic end points only in the fasting state. Future research should investigate glycemic end points in the postprandial state or over a hour period.

: Time-limited meal timing| Time-Restricted Eating and Weight Loss, Mood | The study was a week parallel-arm, randomized controlled weight-loss trial. Aside from when participants ate, all other intervention components were matched across groups. All participants received weight-loss counseling involving energy restriction ER at the UAB Weight Loss Medicine Clinic. In brief, participants received one-on-one counseling from a registered dietitian at baseline minute session and at weeks 2, 6, and 10 minute sessions. Participants were also instructed to attend at least 10 group classes. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more details. The co—primary outcomes were weight loss and fat loss. The secondary outcomes were fasting cardiometabolic risk factors. Additional outcomes included adherence, satisfaction with the eating windows, food intake, physical activity, mood, and sleep. All week 0 and 14 outcomes except adherence and food intake were measured in the morning following a water-only fast of at least 12 hours. In addition, we measured body weight in the nonfasting state in the clinic every 2 weeks throughout the trial. Body composition was measured using dual x-ray absorptiometry DEXA [iDXA; GE-Lunar Radiation Corporation] and analyzed using enCORE software, version 15 GE Healthcare. Fat loss was assessed in 2 ways: as the ratio of fat loss to weight loss primary fat loss end point and as the absolute change in fat mass secondary fat loss end point. To accurately assess the former end point, we limited the analysis to completers who lost at least 3. Fasting blood pressure, glucose levels, insulin levels, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance HOMA-IR , HOMA for β-cell function HOMA-β , hemoglobin A 1c level, and plasma lipid levels were measured using standard procedures see eMethods in Supplement 1. Participants reported when they started and stopped eating daily through surveys administered via REDCap Research Electronic Data Capture software. Days with missing surveys were considered nonadherent. Energy intake and macronutrient composition were measured by 3-day food record using the Remote Food Photography Method. We measured physical activity, mood, sleep, and satisfaction with the eating window using the Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire, the Profile of Moods—Short Form POMS-SF , the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 PHQ-9 , the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire MCTQ , the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PSQI , and a 5-point Likert scale, respectively see eMethods in Supplement 1. The trial was statistically powered to detect a We decided to assess the ratio of fat loss to weight loss only in completers who lost at least 3. Analyses were performed in R, version 4. All analyses were intention-to-treat, except that the ratio of fat loss to weight loss and questionnaire data were analyzed in completers only. End points with 3 or more repeated measures included body weight and adherence and were analyzed using linear mixed models. All other end points were analyzed using multiple imputation by chained equations, followed by linear regression. Between-group analyses were adjusted for age, race Black vs non-Black , and sex male vs female , while baseline data and within-group changes were analyzed using independent t tests. Following our preregistered statistical plan, we also performed a secondary analysis in completers using the same statistical methods. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more statistical details. We screened people and enrolled 90 participants Figure 1. Participants had a mean SD BMI of Adverse events in both groups were mild see eAppendix in Supplement 1. Unfortunately, because of the COVID pandemic, we were unable to collect postintervention data on primary and secondary outcomes in 11 participants see eMethods in Supplement 1. There were also no statistically significant differences in the changes in fat-free mass, trunk fat, visceral fat, waist circumference, or appendicular lean mass Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, glucose levels, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, hemoglobin A 1c level, or plasma lipid levels Table 2. All other mood and sleep end points were similar between groups eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1. All other primary and secondary outcomes were similar between groups eTable 3 in Supplement 1. We conducted a randomized weight-loss trial comparing TRE with eating over a period of 12 or more hours where both groups received the same weight-loss counseling. Our data suggest that eTRE is feasible, as participants adhered 6. Despite the challenges of navigating evening social activities and occupational schedules, adherence to eTRE was similar to that of other TRE interventions approximately 5. Furthermore, we found that eTRE was acceptable for many patients. The key finding of this study is that eTRE was more effective for losing weight than eating over a period of 12 or more hours. In our trial, the eTRE group lost an additional 2. However, our study had better post hoc statistical power owing to less variability in weight loss. Therefore, our results are not incompatible. Furthermore, our eTRE group extended their daily fasting by twice as much, fasting an extra 4. Most previous studies report that TRE reduces energy intake and does not affect physical activity. On the other hand, we found no evidence of selective fat loss, as measured by the ratio of fat loss to weight loss. Also, total fat loss was not statistically significant in the main intention-to-treat analysis. Our finding of a difference in weight loss but not fat loss was likely due to lower statistical power because DEXA scans were performed only twice whereas body weight was measured 8 times and using a conservative imputation approach. In a secondary analysis of completers, eTRE was indeed better for losing body fat and trunk fat than eating over a window of 12 or more hours. The eTRE intervention increased fat loss by an additional 1. The eTRE intervention was also more effective than eating over a period of 12 or more hours for lowering diastolic blood pressure. The effects were clinically significant and on par with those of the DASH Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet 64 and endurance exercise. For comparison, 1 previous controlled feeding study reported that eTRE reduces blood pressure, 17 while other TRE studies are mixed but lean null. Indeed, blood pressure has a pronounced circadian rhythm, 68 and circadian misalignment elevates blood pressure in humans. The eTRE intervention was not more effective for improving other fasting cardiometabolic end points. However, studies on other versions of TRE report more mixed results. We also had larger variability in fasting insulin level relative to our previous trial. Our study has a few limitations, including being modest in duration, enrolling mostly women, and not achieving our intended sample size, partly owing to the COVID pandemic. Also, we measured physical activity by self-report, not by accelerometry, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in physical activity between groups. Finally, we measured cardiometabolic end points only in the fasting state. Future research should investigate glycemic end points in the postprandial state or over a hour period. In this randomized clinical trial, eTRE was more effective for losing weight and lowering diastolic blood pressure than eating over a period of 12 or more hours at 14 weeks. The eTRE intervention may therefore be an effective treatment for both obesity and hypertension. It also improves mood by decreasing fatigue and feelings of depression-dejection and increasing vigor, and those who can stick with eTRE lose more body fat and trunk fat. However, eTRE did not affect most fasting cardiometabolic risk factors in the main intention-to-treat analysis. This trial also lays important groundwork for future IF research. Therefore, future clinical trials will need to enroll much larger sample sizes—up to approximately participants—to determine whether IF affects body composition and cardiometabolic health. Future studies should investigate whether the timing and duration of the eating window affect these results, as well as determine who can adhere to eTRE vs who cannot and would instead benefit from other meal-timing interventions. The eTRE intervention should be further tested as a low-cost, easy-to-implement approach to improve health and treat disease. Published Online: August 8, Corresponding Author: Courtney M. Peterson, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University Blvd, Webb , Birmingham, AL cpeterso uab. Author Contributions: Drs Peterson and Richman had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Jamshed and Steger contributed equally to this work as co—first authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Administrative, technical, or material support: Jamshed, Steger, Bryan, Hanick, Martin, Peterson. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Martin reported grants from the National Institutes of Health NIH during the conduct of the study and personal fees scientific advisory board member from Wondr Health outside the submitted work. Dr Peterson reported grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported. Resources and support were also provided by 2 Nutrition Obesity Research Center NORC grants P30 DK; P30 DK , a Diabetes Research Center DRC grant P30 DK , an NIH Predoctoral T32 Obesity Fellowship to Mr Hanick T32 HL , and the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center LA CaTS; U54 GM The statistician was later changed prior to beginning data analysis. The sponsors had no other roles in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Meeting Presentation: Results from preliminary analyses, which did not use linear mixed modeling, were presented at ObesityWeek and a handful of invited seminars. Full analyses, which included linear mixed models for adherence and weight loss, were conducted later. Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 4. Additional Contributions: We thank the UAB Weight Loss Medicine clinic staff, and Karin Crowell, RD Department of Medicine, UAB , especially, for their support and dedication in conducting this study. We also thank Karissa Neubig, RD Pennington Biomedical Research Center , and Tulsi Patel, BS UAB , for their help in measuring dietary intake and tracking adherence. Ms Crowell and Ms Neubig received no compensation beyond that of their regular employment. Ms Patel received a small stipend. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Comment. Top of Article Key Points Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusions Article Information References. Visual Abstract. Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults With Obesity. View Large Download. Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram. Figure 2. Adherence, Satisfaction, and Acceptability. Figure 3. Weight Loss and Body Composition. Table 1. Baseline Characteristics. Table 2. Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Audio Author Interview Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss and Fat Loss in Adults With Obesity. Subscribe to Podcast. Supplement 1. Adverse Events eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Completers Versus Non-Completers eTable 2. Food Intake and Physical Activity eTable 3. Completers-Only Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcomes eFigure 1. Mood eFigure 2. Supplement 2. Trial Protocol. Supplement 3. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity Silver Spring. Madjd A, Taylor MA, Delavari A, Malekzadeh R, Macdonald IA, Farshchi HR. Beneficial effect of high energy intake at lunch rather than dinner on weight loss in healthy obese women in a weight-loss program: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H, Peterson CM. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Penn Medicine News. Timing meals later at night can cause weight gain and impair fat metabolism. Use limited data to select advertising. Create profiles for personalised advertising. Use profiles to select personalised advertising. Create profiles to personalise content. Use profiles to select personalised content. Measure advertising performance. Measure content performance. Understand audiences through statistics or combinations of data from different sources. Develop and improve services. Use limited data to select content. List of Partners vendors. Wellness Nutrition. By Hallie Levine is an award-winning health and medical journalist who frequently contributes to AARP, Consumer Reports, the New York Times, and Health. Hallie Levine. health's editorial guidelines. Medically reviewed by Jamie Johnson, RDN. Jamie Johnson, RDN, is the owner of the nutrition communications practice Ingraining Nutrition. learn more. Trending Videos. A Meal Plan in 1, Calories. Best Diets for Your Health. Was this page helpful? By the end of the study, researchers observed increased markers of autophagy 1 , suggesting that TRE could potentially have anti-aging effects. Researchers in this study concluded that TRE could reduce inflammation and other age-related changes, resulting in enhanced longevity. While it may sound too good to be true, this found in a pilot study 4 conducted by Gabel and other researchers. The study found that, on average, people who limited their food intake to an eight-hour period each day consumed calories less per day and lost 2. Jamshed notes that TRE may also help regulate levels of ghrelin and leptin, two hormones involved in regulating hunger and satiety. Interestingly, one study found that early time-restricted eating increased feelings of fullness, decreased the desire to eat, and reduced levels of ghrelin the "hunger hormone" , all of which could potentially boost weight loss 5. In addition to supporting weight loss, TRE may promote other aspects of metabolic health as well. Jamshed adds that it may help reduce insulin resistance 6 and increase insulin sensitivity, which can improve your body's ability to use insulin to regulate blood sugar levels effectively. A recent review by Gabel and colleagues theorized that the benefits of TRE could stem from its ability to 6 stimulate autophagy, reduce oxidative stress, and increase the responsiveness of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. There are several simple ways to integrate TRE into your day. Here are some sample schedules for the most popular methods, along with a few of the key pros and cons to consider for each. Early TRE usually restricts food intake to a period earlier in the day and involves fasting in the early afternoon. Sticking to an early eating schedule may help you get the most bang for your buck, according to Jamshed. This is also reflected in multiple studies, which have linked an early time-restricted eating schedule to improved insulin sensitivity 8 , decreased oxidative stress 8 , increased weight loss 9 , and reduced blood pressure levels 9. However, this plan may be challenging to stick to, especially as it involves forgoing family dinners, happy hours, and late-night snacks. It might also not be a good fit if you sleep in or prefer eating your morning meal a bit later in the day. Midday TRE involves limiting your food intake to the middle of the day, often by skipping breakfast and eating an early lunch. However, it may not align with your natural circadian rhythms as well as early TRE, she says, which could diminish some of the possible benefits. In fact, one study comparing the two methods found that early TRE was more effective at improving insulin sensitivity 10 than midday TRE. Early TRE was also associated with reductions in body weight, fasting blood sugar levels, and inflammation, whereas midday TRE was not. Jamshed states that this could be a good option for people who prefer to socialize or eat dinner later in the day, noting that it may still offer some of the benefits of TRE. In fact, a recent trial 11 comparing early and late TRE found that both resulted in similar amounts of weight loss compared to a control group. However, early TRE still had an edge over late eating, especially in terms of its effects on blood sugar, blood pressure, fasting insulin, and insulin resistance. According to Jamshed, late TRE may not be ideal for blood sugar control and fat burning, as our body's sensitivity to insulin tends to decline 12 in the evening. may have more benefits for glucose control," says Gabel. Jamshed agrees, noting that early TRE may be the most effective option when it comes to metabolic health, weight loss, and mood. However, both also acknowledge that this eating pattern may be harder for some people to follow, as many people prefer socializing in the evenings and enjoying dinner with family or friends. Jamshed emphasizes that there's no single "best" type of TRE for everyone, as the most appropriate option can vary depending on many individual factors. Ultimately, it may be best to tailor your eating pattern to your individual schedule and experiment with the precise timing to find what works for you. And as far as how long to fast, if you're new to time-restricted eating, consider checking out and fasting plans, both of which involve abstaining from food for 18 or 16 hours each day, respectively. While there's no one-size-fits-all plan when it comes to time-restricted eating, these are two of the most popular and beginner-friendly variations. Though TRE may offer several possible health benefits, it's not a good fit for everyone. Gabel states that intermittent fasting in general is not recommended for children, adolescents, people with a history of eating disorders, and those who are underweight. Additionally, she notes that there is limited research on the safety of fasting for other groups, including people who are pregnant or lactating and individuals over the age of Jamshed points out that there are several possible time-restricted eating side effects to keep in mind, including:. Following an early time-restricted eating schedule may offer the most benefits in terms of weight loss and metabolic health. However, it's important to pick a schedule based on what works for you and your lifestyle and what you're most likely to follow. Time-restricted eating has been shown to support weight loss in several studies. Of course, it's best to pair time-restricted eating with a nutritious, well-rounded diet and regular physical activity to maximize your results. Time-restricted eating is a flexible eating pattern that may offer benefits in the long run, including increased weight loss and improved metabolic health. Additionally, there are several variations available, making it easy to incorporate TRE into your schedule. |

| Site Index | Satchidananda Panda, a co-author of the firefighter study and professor at the Salk Institute, said a hour window seems to be a "sweet spot" because the more severe restriction that characterizes many intermittent fasting diets is hard to maintain. However, other research using a similar length of eating window did not show any benefits on cholesterol levels 9. Mood and Sleep. Ms Patel received a small stipend. Study co-author Dr. |

| A 10-hour eating window could reduce risk factors for heart disease | Meeting Presentation: Results from preliminary analyses, which did not use linear mixed modeling, were presented at ObesityWeek and a handful of invited seminars. Full analyses, which included linear mixed models for adherence and weight loss, were conducted later. Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 4. Additional Contributions: We thank the UAB Weight Loss Medicine clinic staff, and Karin Crowell, RD Department of Medicine, UAB , especially, for their support and dedication in conducting this study. We also thank Karissa Neubig, RD Pennington Biomedical Research Center , and Tulsi Patel, BS UAB , for their help in measuring dietary intake and tracking adherence. Ms Crowell and Ms Neubig received no compensation beyond that of their regular employment. Ms Patel received a small stipend. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Comment. Top of Article Key Points Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusions Article Information References. Visual Abstract. Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults With Obesity. View Large Download. Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram. Figure 2. Adherence, Satisfaction, and Acceptability. Figure 3. Weight Loss and Body Composition. Table 1. Baseline Characteristics. Table 2. Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Audio Author Interview Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss and Fat Loss in Adults With Obesity. Subscribe to Podcast. Supplement 1. Adverse Events eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Completers Versus Non-Completers eTable 2. Food Intake and Physical Activity eTable 3. Completers-Only Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcomes eFigure 1. Mood eFigure 2. Supplement 2. Trial Protocol. Supplement 3. Statistical Analysis Plan. Supplement 4. Data Sharing Statement. Smyers ME, Koch LG, Britton SL, Wagner JG, Novak CM. Enhanced weight and fat loss from long-term intermittent fasting in obesity-prone, low-fitness rats. doi: Gotthardt JD, Verpeut JL, Yeomans BL, et al. Intermittent fasting promotes fat loss with lean mass retention, increased hypothalamic norepinephrine content, and increased neuropeptide Y gene expression in diet-induced obese male mice. Hutchison AT, Liu B, Wood RE, et al. Effects of intermittent versus continuous energy intakes on insulin sensitivity and metabolic risk in women with overweight. Byrne NM, Sainsbury A, King NA, Hills AP, Wood RE. Intermittent energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in obese men: the MATADOR study. Catenacci VA, Pan Z, Ostendorf D, et al. A randomized pilot study comparing zero-calorie alternate-day fasting to daily caloric restriction in adults with obesity. Harvie M, Wright C, Pegington M, et al. The effect of intermittent energy and carbohydrate restriction v. daily energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers in overweight women. Keenan S, Cooke MB, Belski R. The effects of intermittent fasting combined with resistance training on lean body mass: a systematic review of human studies. Kessler CS, Stange R, Schlenkermann M, et al. Moro T, Tinsley G, Bianco A, et al. Razavi R, Parvaresh A, Abbasi B, et al. The alternate-day fasting diet is a more effective approach than a calorie restriction diet on weight loss and hs-CRP levels. Tinsley GM, Moore ML, Graybeal AJ, et al. Time-restricted feeding plus resistance training in active females: a randomized trial. Schübel R, Nattenmüller J, Sookthai D, et al. Effects of intermittent and continuous calorie restriction on body weight and metabolism over 50 wk: a randomized controlled trial. Antoni R, Johnston KL, Steele C, Carter D, Robertson MD, Capehorn MS. Efficacy of an intermittent energy restriction diet in a primary care setting. Davoodi SH, Ajami M, Ayatollahi SA, Dowlatshahi K, Javedan G, Pazoki-Toroudi HR. Calorie shifting diet versus calorie restriction diet: a comparative clinical trial study. PubMed Google Scholar. Cai H, Qin Y-L, Shi Z-Y, et al. Effects of alternate-day fasting on body weight and dyslipidaemia in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lin YJ, Wang YT, Chan LC, Chu NF. Effect of time-restricted feeding on body composition and cardio-metabolic risk in middle-aged women in Taiwan. Sutton EF, Beyl R, Early KS, Cefalu WT, Ravussin E, Peterson CM. Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Miu P, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Sherman H, Genzer Y, Cohen R, Chapnik N, Madar Z, Froy O. Timed high-fat diet resets circadian metabolism and prevents obesity. Gabel K, Hoddy KK, Haggerty N, et al. Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: a pilot study. Anton SD, Lee SA, Donahoo WT, et al. The effects of time restricted feeding on overweight, older adults: a pilot study. Chow LS, Manoogian ENC, Alvear A, et al. Time-restricted eating effects on body composition and metabolic measures in humans who are overweight: a feasibility study. Gill S, Panda S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cienfuegos S, Gabel K, Kalam F, et al. Effects of 4- and 6-h time-restricted feeding on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized controlled trial in adults with obesity. Kesztyüs D, Cermak P, Gulich M, Kesztyüs T. Adherence to time-restricted feeding and impact on abdominal obesity in primary care patients: results of a pilot study in a pre-post design. Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, et al. Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. McAllister MJ, Pigg BL, Renteria LI, Waldman HS. Time-restricted feeding improves markers of cardiometabolic health in physically active college-age men: a 4-week randomized pre-post pilot study. Che T, Yan C, Tian D, Zhang X, Liu X, Wu Z. Time-restricted feeding improves blood glucose and insulin sensitivity in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Adafer R, Messaadi W, Meddahi M, et al. Chen JH, Lu LW, Ge Q, et al. Missing puzzle pieces of time-restricted-eating TRE as a long-term weight-loss strategy in overweight and obese people? a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Published online September 23, Moon S, Kang J, Kim SH, et al. Beneficial effects of time-restricted eating on metabolic diseases: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ravussin E, Beyl RA, Poggiogalle E, Hsia DS, Peterson CM. Early time-restricted feeding reduces appetite and increases fat oxidation but does not affect energy expenditure in humans. Martens CR, Rossman MJ, Mazzo MR, et al. Short-term time-restricted feeding is safe and feasible in non-obese healthy midlife and older adults. Hutchison AT, Regmi P, Manoogian ENC, et al. Time-restricted feeding improves glucose tolerance in men at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover trial. Jones R, Pabla P, Mallinson J, et al. Two weeks of early time-restricted feeding eTRF improves skeletal muscle insulin and anabolic sensitivity in healthy men. Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H, Peterson CM. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Marinac CR, Nelson SH, Breen CI, et al. Prolonged nightly fasting and breast cancer prognosis. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. IE 11 is not supported. For an optimal experience visit our site on another browser. SKIP TO CONTENT. NBC News Logo. Kansas City shooting Politics U. My News Manage Profile Email Preferences Sign Out. Search Search. Profile My News Sign Out. Sign In Create your free profile. Sections U. tv Today Nightly News MSNBC Meet the Press Dateline. Featured NBC News Now Nightly Films Stay Tuned Special Features Newsletters Podcasts Listen Now. More From NBC CNBC NBC. COM NBCU Academy Peacock NEXT STEPS FOR VETS NBC News Site Map Help. Follow NBC News. news Alerts There are no new alerts at this time. Facebook Twitter Email SMS Print Whatsapp Reddit Pocket Flipboard Pinterest Linkedin. Why People Love Snow So Much Taylor Swift Is TIME's Person of the Year Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time. You May Also Like. TIME Logo. Home U. Politics World Health Business Tech Personal Finance by TIME Stamped Shopping by TIME Stamped Future of Work by Charter Entertainment Ideas Science History Sports Magazine The TIME Vault TIME For Kids TIME CO2 Coupons TIME Edge Video Masthead Newsletters Subscribe Subscriber Benefits Give a Gift Shop the TIME Store Careers Modern Slavery Statement Press Room TIME Studios U. All Rights Reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Service , Privacy Policy Your Privacy Rights and Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information. TIME may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. |

| The Best Times to Eat | Whether or not it actually decreases the amount of food eaten probably varies by individual. Time-restricted eating may have several health benefits, including weight loss, better heart health and lower blood sugar levels. However, other studies in normal-weight people have reported no weight loss with eating windows of similar duration 2 , 9. Whether or not you will experience weight loss with time-restricted eating probably depends on whether or not you manage to eat fewer calories within the eating period If this style of eating helps you eat fewer calories each day, it can produce weight loss over time. If this is not the case for you, time-restricted eating may not be your best bet for weight loss. Several substances in your blood can affect your risk of heart disease, and one of these important substances is cholesterol. However, other research using a similar length of eating window did not show any benefits on cholesterol levels 9. Both studies used normal-weight adults, so the inconsistent results may be due to differences in weight loss. When participants lost weight with time-restricted eating, their cholesterol improved. When they did not lose weight, it did not improve 8 , 9. Several studies have shown that slightly longer eating windows of 10—12 hours may also improve cholesterol. Having too much sugar in your blood can lead to diabetes and damage several parts of your body. Time-restricted eating is very simple — simply choose a certain number of hours during which you will eat all your calories each day. If you are using time-restricted eating to lose weight and improve your health, the number of hours you allow yourself to eat should be less than the number you typically allow. For example, if you normally eat your first meal at 8 a. and keep eating until around 9 p. To use time-restricted eating, you would reduce this number. For example, you may want to choose to only eat during a window of 8—9 hours. Because time-restricted eating focuses on when you eat rather than what you eat, it can also be combined with any type of diet, such as a low-carb diet or high-protein diet. If you exercise regularly , you may wonder how time-restricted eating will affect your workouts. One eight-week study examined time-restricted eating in young men who followed a weight-training program. It found that the men performing time-restricted eating were able to increase their strength just as much as the control group that ate normally A similar study in adult men who weight trained compared time-restricted eating during an 8-hour eating window to a normal eating pattern. Based on these studies, it appears that you can exercise and make good progress while following a time-restricted eating program. However, research is needed in women and those performing an aerobic exercise like running or swimming. Time-restricted eating is a dietary strategy that focuses on when you eat, rather than what you eat. By limiting all your daily food intake to a shorter period of time, it may be possible to eat less food and lose weight. Make your journey into scheduled eating a little more manageable. When you lose weight, your body responds by burning fewer calories, which is often referred to as starvation mode. This article investigates the…. Discover which diet is best for managing your diabetes. Getting enough fiber is crucial to overall gut health. Let's look at some easy ways to get more into your diet:. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Nutrition Evidence Based Time-Restricted Eating: A Beginner's Guide. By Grant Tinsley, Ph. Intermittent fasting is currently one of the most popular nutrition programs around. What Is Time-Restricted Eating? Share on Pinterest. six hours or 9 a. eight hours. Nisa Maruthur, an associate professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, agrees. However, establishing temporal boundaries can help. and 4 p. Contact us at letters time. Alarm clock and plate with cutlery. By Tara Law. January 20, PM EST. Why People Love Snow So Much Taylor Swift Is TIME's Person of the Year Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time. You May Also Like. TIME Logo. Home U. |

| Chrononutrition: Does the Timing of Your Meals Matter? | New research suggests that running may not aid much with weight loss, but it can help you keep from gaining weight as you age. Here's why. New research finds that bariatric surgery is an effective long-term treatment to help control high blood pressure. Most people associate stretch marks with weight gain, but you can also develop stretch marks from rapid weight loss. New research reveals the states with the highest number of prescriptions for GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy. Mounjaro is a diabetes medication that may help with weight loss. Here's what you need to know about purchasing it without insurance. Eating up to three servings of kimchi each day is linked to a reduced rate of obesity among men, according to a new study. This study is observational…. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Health News Fact Checked How Eating Only Between 7 a. Can Help With Weight Loss and Blood Pressure. By Elizabeth Pratt on August 8, — Fact checked by Dana K. Share on Pinterest Researchers eating in the morning and afternoon only can help with weight loss. Time of day matters. Benefits besides weight loss. How to start on a diet plan. This refers to any eating plan that alternates between periods of restricting calories and eating normally. Although TRE will not work for everyone, some may find it beneficial. Recent studies have shown that it can aid weight loss and may lower the risk of metabolic diseases, such as diabetes. TRE may help a person eat less without counting calories. It may also be a healthy way to avoid common diet pitfalls, such as late-night snacking. However, people with diabetes or other health issues can consider speaking with a doctor before trying this type of eating pattern. No single eating plan will work for everyone to lose weight. While some people are likely to meet weight loss goals with TRE, others may not benefit from it. It is best for a person to speak with a doctor before trying TRE or any other eating plan. Recent studies involving people of different ages and in different research settings show that TRE has the potential to lead to weight loss and health improvement:. Some research notes that health benefits may happen even if people do not lose weight as a result of trying TRE. Cell Metabolism has published one of the most rigorously conducted randomized controlled trials to date. It found that when eight males with prediabetes who were overweight followed early-TRE for 5 weeks, several markers of heart health were improved, including:. The observed improvements in heart health occured even when the TRE group did not lose weight, and they reported a lower desire to eat in the evening. Researchers need further studies done on more people over longer periods of time to confirm these findings. Accumulating research suggests that TRE has potential, but not all studies show it is more effective for weight loss than daily regular calorie restriction. A review concluded that intermittent calorie restriction, including TRE, offers no significant advantage over limiting calorie intake each day. More recently, a randomized controlled clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine showed TRE had no weight loss benefit after 12 months. In the trial, people with obesity followed TRE while also eating fewer calories or followed daily calorie restriction alone. When the study ended, there were no differences between the groups for weight loss. Studies from and note that TRE results in equal weight loss to regular daily calorie restriction in people who are overweight or have obesity. Because of this, it is possible for TRE to be an option for people who want an alternate solution to daily calorie restriction for weight loss. Other research does not show any benefit of TRE for weight loss compared with eating regularly throughout the day with no calorie restriction. This includes when study participants receive no instruction to change their food choices or activity levels. As the science on TRE for weight loss advances, some researchers have expressed the need for caution around who might consider following TRE. Among people who are overweight or have obesity, some studies have found that weight loss in TRE may be due to the loss of lean mass muscle versus fat mass adipose tissue. Therefore, it is especially important for people who are overweight or have obesity and who also have comorbidities such as sarcopenia to talk with a doctor before trying TRE. The current evidence base shows promise for the role of TRE in weight loss in the short term from studies lasting less than 6 months. However, researchers need longer-term studies with larger numbers of more diverse participants to determine whether TRE can lead to clinically meaningful weight loss that a person can maintain over time. A study from the journal Appetite aimed to look at the barriers to or facilitators of following TRE over the long term. It used 20 middle-aged adults who were overweight or had obesity and were at risk of type 2 diabetes. The researchers assessed how easily people could incorporate TRE into daily life following a 3-month study with structured interviews. Seven study participants kept up with their instructions on TRE from the study, 10 adjusted their approach to follow a different version of their original instructions, and three did not follow through with their instructions. Researchers need more work to understand how TRE influences the biological, behavioral, psychosocial, and environmental facilitators of and barriers to successful long-term weight maintenance. One study investigated TRE in 11 adults who were overweight. They followed early-TRE for 4 days, where they ate between 8 a. and 2 p. and 8 p. The authors concluded that when participants followed the early-TRE plan, they had increased activity of mTOR. This is a protein marker thought to be involved in maintaining muscle mass. A study, in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , randomly assigned 16 otherwise healthy males to follow early-TRE for 2 weeks or just regular calorie restriction. It found the TRE group saw an improved ability for their muscle to use glucose and branched-chain amino acids. A study in Scientific Reports assigned 46 otherwise healthy older males to follow 6 weeks of either TRE or their regular eating plan. The TRE group had no significant changes in their muscle mass. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan appear in Supplement 2 and Supplement 3 , respectively. The study was a week parallel-arm, randomized controlled weight-loss trial. Aside from when participants ate, all other intervention components were matched across groups. All participants received weight-loss counseling involving energy restriction ER at the UAB Weight Loss Medicine Clinic. In brief, participants received one-on-one counseling from a registered dietitian at baseline minute session and at weeks 2, 6, and 10 minute sessions. Participants were also instructed to attend at least 10 group classes. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more details. The co—primary outcomes were weight loss and fat loss. The secondary outcomes were fasting cardiometabolic risk factors. Additional outcomes included adherence, satisfaction with the eating windows, food intake, physical activity, mood, and sleep. All week 0 and 14 outcomes except adherence and food intake were measured in the morning following a water-only fast of at least 12 hours. In addition, we measured body weight in the nonfasting state in the clinic every 2 weeks throughout the trial. Body composition was measured using dual x-ray absorptiometry DEXA [iDXA; GE-Lunar Radiation Corporation] and analyzed using enCORE software, version 15 GE Healthcare. Fat loss was assessed in 2 ways: as the ratio of fat loss to weight loss primary fat loss end point and as the absolute change in fat mass secondary fat loss end point. To accurately assess the former end point, we limited the analysis to completers who lost at least 3. Fasting blood pressure, glucose levels, insulin levels, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance HOMA-IR , HOMA for β-cell function HOMA-β , hemoglobin A 1c level, and plasma lipid levels were measured using standard procedures see eMethods in Supplement 1. Participants reported when they started and stopped eating daily through surveys administered via REDCap Research Electronic Data Capture software. Days with missing surveys were considered nonadherent. Energy intake and macronutrient composition were measured by 3-day food record using the Remote Food Photography Method. We measured physical activity, mood, sleep, and satisfaction with the eating window using the Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire, the Profile of Moods—Short Form POMS-SF , the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 PHQ-9 , the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire MCTQ , the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PSQI , and a 5-point Likert scale, respectively see eMethods in Supplement 1. The trial was statistically powered to detect a We decided to assess the ratio of fat loss to weight loss only in completers who lost at least 3. Analyses were performed in R, version 4. All analyses were intention-to-treat, except that the ratio of fat loss to weight loss and questionnaire data were analyzed in completers only. End points with 3 or more repeated measures included body weight and adherence and were analyzed using linear mixed models. All other end points were analyzed using multiple imputation by chained equations, followed by linear regression. Between-group analyses were adjusted for age, race Black vs non-Black , and sex male vs female , while baseline data and within-group changes were analyzed using independent t tests. Following our preregistered statistical plan, we also performed a secondary analysis in completers using the same statistical methods. See eMethods in Supplement 1 for more statistical details. We screened people and enrolled 90 participants Figure 1. Participants had a mean SD BMI of Adverse events in both groups were mild see eAppendix in Supplement 1. Unfortunately, because of the COVID pandemic, we were unable to collect postintervention data on primary and secondary outcomes in 11 participants see eMethods in Supplement 1. There were also no statistically significant differences in the changes in fat-free mass, trunk fat, visceral fat, waist circumference, or appendicular lean mass Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, glucose levels, insulin levels, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, hemoglobin A 1c level, or plasma lipid levels Table 2. All other mood and sleep end points were similar between groups eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1. All other primary and secondary outcomes were similar between groups eTable 3 in Supplement 1. We conducted a randomized weight-loss trial comparing TRE with eating over a period of 12 or more hours where both groups received the same weight-loss counseling. Our data suggest that eTRE is feasible, as participants adhered 6. Despite the challenges of navigating evening social activities and occupational schedules, adherence to eTRE was similar to that of other TRE interventions approximately 5. Furthermore, we found that eTRE was acceptable for many patients. The key finding of this study is that eTRE was more effective for losing weight than eating over a period of 12 or more hours. In our trial, the eTRE group lost an additional 2. However, our study had better post hoc statistical power owing to less variability in weight loss. Therefore, our results are not incompatible. Furthermore, our eTRE group extended their daily fasting by twice as much, fasting an extra 4. Most previous studies report that TRE reduces energy intake and does not affect physical activity. On the other hand, we found no evidence of selective fat loss, as measured by the ratio of fat loss to weight loss. Also, total fat loss was not statistically significant in the main intention-to-treat analysis. Our finding of a difference in weight loss but not fat loss was likely due to lower statistical power because DEXA scans were performed only twice whereas body weight was measured 8 times and using a conservative imputation approach. In a secondary analysis of completers, eTRE was indeed better for losing body fat and trunk fat than eating over a window of 12 or more hours. The eTRE intervention increased fat loss by an additional 1. The eTRE intervention was also more effective than eating over a period of 12 or more hours for lowering diastolic blood pressure. The effects were clinically significant and on par with those of the DASH Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet 64 and endurance exercise. For comparison, 1 previous controlled feeding study reported that eTRE reduces blood pressure, 17 while other TRE studies are mixed but lean null. Indeed, blood pressure has a pronounced circadian rhythm, 68 and circadian misalignment elevates blood pressure in humans. The eTRE intervention was not more effective for improving other fasting cardiometabolic end points. However, studies on other versions of TRE report more mixed results. We also had larger variability in fasting insulin level relative to our previous trial. Our study has a few limitations, including being modest in duration, enrolling mostly women, and not achieving our intended sample size, partly owing to the COVID pandemic. Also, we measured physical activity by self-report, not by accelerometry, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in physical activity between groups. Finally, we measured cardiometabolic end points only in the fasting state. Future research should investigate glycemic end points in the postprandial state or over a hour period. In this randomized clinical trial, eTRE was more effective for losing weight and lowering diastolic blood pressure than eating over a period of 12 or more hours at 14 weeks. The eTRE intervention may therefore be an effective treatment for both obesity and hypertension. It also improves mood by decreasing fatigue and feelings of depression-dejection and increasing vigor, and those who can stick with eTRE lose more body fat and trunk fat. However, eTRE did not affect most fasting cardiometabolic risk factors in the main intention-to-treat analysis. This trial also lays important groundwork for future IF research. Therefore, future clinical trials will need to enroll much larger sample sizes—up to approximately participants—to determine whether IF affects body composition and cardiometabolic health. Future studies should investigate whether the timing and duration of the eating window affect these results, as well as determine who can adhere to eTRE vs who cannot and would instead benefit from other meal-timing interventions. The eTRE intervention should be further tested as a low-cost, easy-to-implement approach to improve health and treat disease. Published Online: August 8, Corresponding Author: Courtney M. Peterson, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University Blvd, Webb , Birmingham, AL cpeterso uab. Author Contributions: Drs Peterson and Richman had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs Jamshed and Steger contributed equally to this work as co—first authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Administrative, technical, or material support: Jamshed, Steger, Bryan, Hanick, Martin, Peterson. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Martin reported grants from the National Institutes of Health NIH during the conduct of the study and personal fees scientific advisory board member from Wondr Health outside the submitted work. Dr Peterson reported grants from the NIH during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported. Resources and support were also provided by 2 Nutrition Obesity Research Center NORC grants P30 DK; P30 DK , a Diabetes Research Center DRC grant P30 DK , an NIH Predoctoral T32 Obesity Fellowship to Mr Hanick T32 HL , and the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center LA CaTS; U54 GM The statistician was later changed prior to beginning data analysis. The sponsors had no other roles in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Meeting Presentation: Results from preliminary analyses, which did not use linear mixed modeling, were presented at ObesityWeek and a handful of invited seminars. Full analyses, which included linear mixed models for adherence and weight loss, were conducted later. Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 4. Additional Contributions: We thank the UAB Weight Loss Medicine clinic staff, and Karin Crowell, RD Department of Medicine, UAB , especially, for their support and dedication in conducting this study. We also thank Karissa Neubig, RD Pennington Biomedical Research Center , and Tulsi Patel, BS UAB , for their help in measuring dietary intake and tracking adherence. Ms Crowell and Ms Neubig received no compensation beyond that of their regular employment. Ms Patel received a small stipend. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Comment. Top of Article Key Points Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusions Article Information References. Visual Abstract. Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults With Obesity. View Large Download. Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram. Figure 2. Adherence, Satisfaction, and Acceptability. Figure 3. Weight Loss and Body Composition. Table 1. Baseline Characteristics. Table 2. Body Composition and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Audio Author Interview Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss and Fat Loss in Adults With Obesity. Subscribe to Podcast. Supplement 1. Adverse Events eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of Completers Versus Non-Completers eTable 2. Food Intake and Physical Activity eTable 3. Completers-Only Analysis of Primary and Secondary Outcomes eFigure 1. Mood eFigure 2. Supplement 2. Trial Protocol. |

Ich berate Ihnen, die Webseite, mit den Artikeln nach dem Sie interessierenden Thema zu suchen.